Jessica Pegula Lives For the Grind

Yes She Can

Yes She Can

Interview: Jessica Pegula lives for the grind.

Interview: Jessica Pegula lives for the grind.

By Reem Abulleil

February 26, 2026

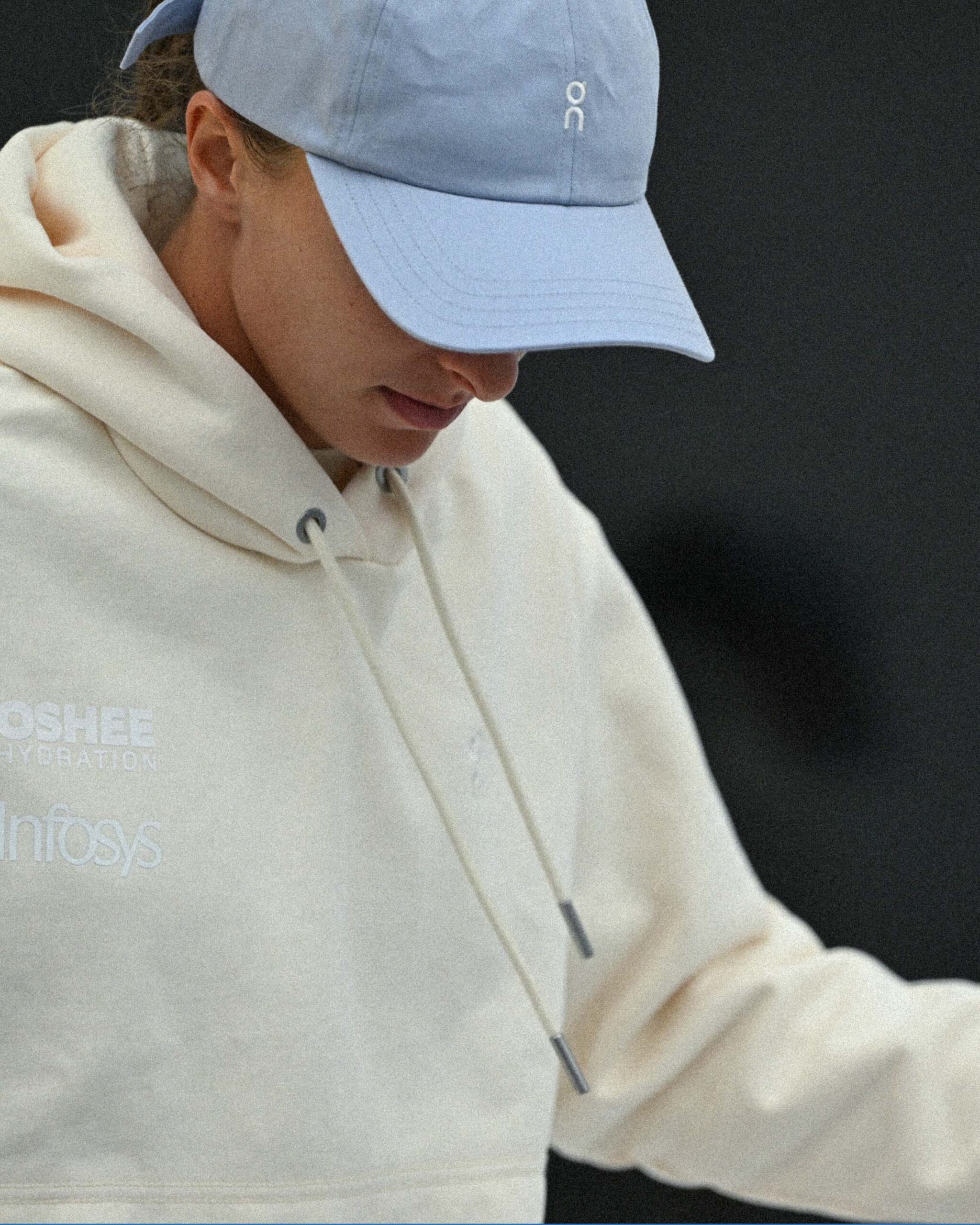

J-Peg won her 10th singles title last week in Dubai. // Getty

Jessica Pegula won her 10th singles title last week in Dubai. // Getty

Jessica Pegula is a mystery to many people. Zheng Qinwen, the Chinese tennis star, recently told her during a brief cameo she made in a video Pegula was filming that “in China we say, ‘Why [does] such a rich girl play tennis? Tennis is such a hard sport, why are you not in [that] high-class life?’” Pegula burst into laughter.

The 32-year-old American comes from a wealthy family that owns the NFL’s Buffalo Bills and NHL’s Buffalo Sabres. Zheng’s candid moment in that video posed a question that crosses many people’s minds. It’s notable given her upbringing, however, that Pegula is one of the hardest-working players in tennis. A near-constant fixture among the top five in most matches played and most matches won during the past four seasons, Pegula lives for the grind and rarely complains about it.

She hasn’t lost before the semifinals since before the US Open last summer—that’s seven straight tournaments where she’s made the final four or better. And as she was battling through a tricky draw in Dubai last week en route to her 10th career title, the WTA announced Pegula as the chair of a newly established Tour Architecture Council, dedicated to introducing much-needed reforms to the tennis circuit’s schedule. Pegula has served as a representative on the WTA Player Council for the past six years, and she now has another role to add to her already busy work schedule.

When the announcement landed in my inbox, I had to ask Pegula where she finds the energy for these extracurricular activities, and more important, what’s been motivating her to take on these roles?

“I don’t know. People just ask me to do things, and I tend to say yes to everything,” she told me with her signature mix of nonchalance and deadpan humor. “I don’t really say no very often. I think in a sense, though, I’m pretty laid-back. I don’t get overly stressed very easily. I think because I’m able to manage a lot of things naturally, maybe, with my personality, that it doesn’t quite worry me and stress me out.”

The problematic tour schedule has been a hot topic for years, and players have been particularly critical of it in the past two seasons, ever since the WTA increased the number of mandatory tournaments in 2024.

Pegula and her fellow Player Council representatives have tried in vain to steer the WTA in a different direction, but their recommendations for the calendar have been pretty much falling on deaf ears. As it stands, players are required to compete in four Grand Slams, 10 WTA 1000s, six WTA 500s, and the WTA Finals, if they qualify for it, in a single season.

That mandate is getting harder and harder to fulfill, and players have started to take matters into their own hands by simply not showing up to events. The WTA 1000 in Dubai last week witnessed 24 withdrawals and retirements—including the world’s top two—before and during the tournament.

The idea of this new Tour Architecture Council is to implement necessary changes to the calendar as early as next season. Given her experience on the WTA Player Council, and the lack of action surrounding schedule reform, does Pegula have reason to believe this new committee will be any different?

The answer is: Yes. She says Valerie Camillo, the new WTA chair who was appointed three months ago, wants to make a point of really listening to the players and making a swift and positive impact.

“I think in the past the WTA has been a little bit slow to make some changes. So I think it’s more sending a message that [Valerie] is really committed to it, the council’s really committed to trying to make change,” said Pegula. “I think it’s kind of just a, ‘Hey, we hear you and we’re trying to make a difference here and we’re going to try and do this the best, fastest way possible.’

“I think just having my name there as a top player will kind of help steer that.”

Ultimately, Pegula accepts these behind-the-scenes roles because she believes change is necessary, believes she has the capability of accelerating that change, and believes her laid-back approach makes her a great candidate for the job.

Some people might not get why Pegula does the things she does, but she always has her reasons, even when she feels the masses aren’t necessarily backing her.

“I definitely get the feeling that people don’t want to root for me because it’s not more of like the fairy-tale, Cinderella story, which is fine, and I’m okay with that,” she once told me at the 2022 WTA Finals in Fort Worth.

Recently Pegula started a podcast called The Player’s Box with three of her fellow American tennis players—Madison Keys, Jennifer Brady, and Desirae Krawczyk. Their conversations are unfiltered and give you the sense that you’re part of their WhatsApp group chat, listening in to the random things that happen to them on tour. Pegula feels the podcast has made her and her cohosts more relatable to fans and has allowed them to showcase their personalities.

The video Zheng appeared in was one where Pegula and Krawczyk were tasting and rating an alarming number of the viral Dubai chocolate bars. (Pegula later made sure to clarify they filmed that video pre-tournament, and she was not eating a bunch of chocolates while she was playing, and winning, a tournament.)

It quickly turned into comedy gold when Krawczyk brought up the nickname Chinese fans have given Pegula, “Da fu,” which translates to “Big Rich,” and Zheng dropped that “high-class life” zinger.

I had to get an answer for the Chinese fans wondering why Pegula bothers to play tennis for a living.

“It’s something I’ve loved to do since I was a kid, since before I had anything about my family or money or the teams or stuff like that,” said Pegula. “I wanted to be No. 1 in the world when I was, like, 6 years old. It’s been my dream for as long as I can remember to be No. 1, to be able to play on tour, to be able to win Slams. I mean, it’s pretty cool that I can look back and say that I’m putting myself in contention to do that, living out my dream.”

At 32, Pegula says her source of motivation is making sure she doesn’t feel stagnant and that she continues to improve. She believes in “trying things” and says that drives her even more than victories and titles. She often overwhelms her coaches by throwing at them a million ideas of things they should be working on. They in turn urge her to slow down and tackle things one at a time.

“At the end of the day, are you really challenging yourself as a person and as a competitor and as a tennis player to get better?” she says. “That’s always been my source of motivation.”

Like I said, she always has her reasons.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Arthur Fils Understands the Assignment

Back on Track

Back on Track

Arthur Fils understands the assignment.

Arthur Fils understands the assignment.

By Carole Bouchard

February 26, 2026

Arthur Fils found his form again in Doha last week. // Getty

Arthur Fils found his form again in Doha last week. // Getty

When Arthur Fils returned to competition in Montpellier this month, for the first time since Toronto last summer, the question was not how long it would take him to get back to his best level, but if he’d ever be able to find the form he needs to matter on tour. Fils stunned the tennis world by trying to come back in Toronto last summer after discovering two stress fractures in his spine at Roland-Garros, having struggled with back pain since Miami. He stunned in a different way last week in Doha by reaching the final just a few weeks after starting his 2026 season.

“I didn’t know I was going to play that well that fast, for sure,” Fils said in Doha. “You don’t really know what to expect when you are back from an injury like eight months. I’m pretty happy with the way I’m playing now. It’s not my best tennis yet, but we’re getting there. I found out I was pretty strong mentally, as I didn’t really ask myself whether I’d be back. I was sure I would be back at my level, and for sure at a higher level.”

Fils, who cut significant weight to protect his back, reached the quarters in Montpellier at the start of the month, beaten by future champion Felix Auger-Aliassime. He then lost his first match in Rotterdam against Alex de Minaur, who would go on to win the title. Nobody was reading too much into these matches for a player who had been out for months and was just starting to claw his way back, a climb that is notoriously more and more difficult these days due to the depth of the field. Well, Fils said “Hold my baguette” to all this and tore through the draw in Doha, defeating Kamil Majchrzak, Quentin Halys, Jiri Lehecka, and Jacub Mensik before falling, like everybody else this year so far, against Carlos Alcaraz. Guaranteed to get back into the top 40, Fils was so impressive that people started to ask him again about challenging the Jannik Sinner and Alcaraz duopoly!

Yet, after the way he got crushed in the final—losing in just 50 minutes—Fils saw that the gap was much wider right now than when he pushed Carlitos to the third set in Monte-Carlo last spring. Logical for someone just returning to it all, but still crushing. “I need to stay positive: It was a very good week, and I made the final. It was much more complicated for me, but these are things that can happen, and we have to move forward. I played less well than I did the rest of the week, but he’s No. 1, hasn’t lost a match since the start of the year, and I think you can see why. For now, it’s another level. I’m not there yet. I’m not there at all. I’ll work for it, but for now, I’m not there at all.”

But there’s a future where he can get there, and that’s the thing: Nobody doubts that Fils, who reached a career high of 14th last year, can be a legit contender for the biggest titles when healthy, with that heavy whip of a forehand and a fearless attitude. Nobody doubts how badly he wants it, either. Here’s a player who says he wants to win Grand Slam titles, who truly believes it and puts the work behind his words. It’s not always the case. New evidence of this occurred in Doha when, out of the blue, Goran Ivanisevic appeared in his box alongside his coach. You don’t commit to hiring that legend if you’re not serious about your ambition.

“He knows my coach, Ivan Cinkus, very well, so the connection was pretty easy. We decided to take a shot and try. It’s working pretty well for now. I have a lot of ambition: Since I was very young, I’ve wanted to be one of the best tennis players and to try my best to win some great titles, some Slams,” Fils said in Doha. “Everyone knows I’m one of the best when I play well, but I need to be one of the best when I play badly.”

I was personally reassured to hear Fils confirming he wouldn’t push his body too hard just now, whatever the results. He’s indeed now in a tricky situation: He’s young and very promising; he has sponsors to satisfy, money to earn; and after being deprived of competition for months, he’s very hungry to go out there and fulfill that potential. But there’s no way to avoid the fact that his career hangs on that testy back now.

His only way to the top will be through extreme cautiousness: “For now, everything is fine with my back. It’s holding up, so we keep going. Now it’s also about being smart about it all and not pushing too much.” Fils didn’t play in Dubai after his performance in Doha, withdrawing ahead of his first match against Jiri Lehecka, citing hip injury.

The reality is that Arthur Fils is surely France’s best hope to (finally) win a men’s Grand Slam title again and surely the player who’s the most ready to do what it takes to succeed, but he might also be the most fragile. In Doha, we had a glimpse again of how great Fils could be. Now it’s about him having the chance to turn it into a full-time reality, freed from that sword of Damocles that hopefully no longer dangles above his spine.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Meddy and Stef: A Recipe For Weirdness

A Recipe For Weirdness

A Recipe For Weirdness

Medvedev vs. Tsitsipas doesn't mean what it used to.

Medvedev vs. Tsitsipas doesn't mean what it used to.

By Giri Nathan

February 20, 2026

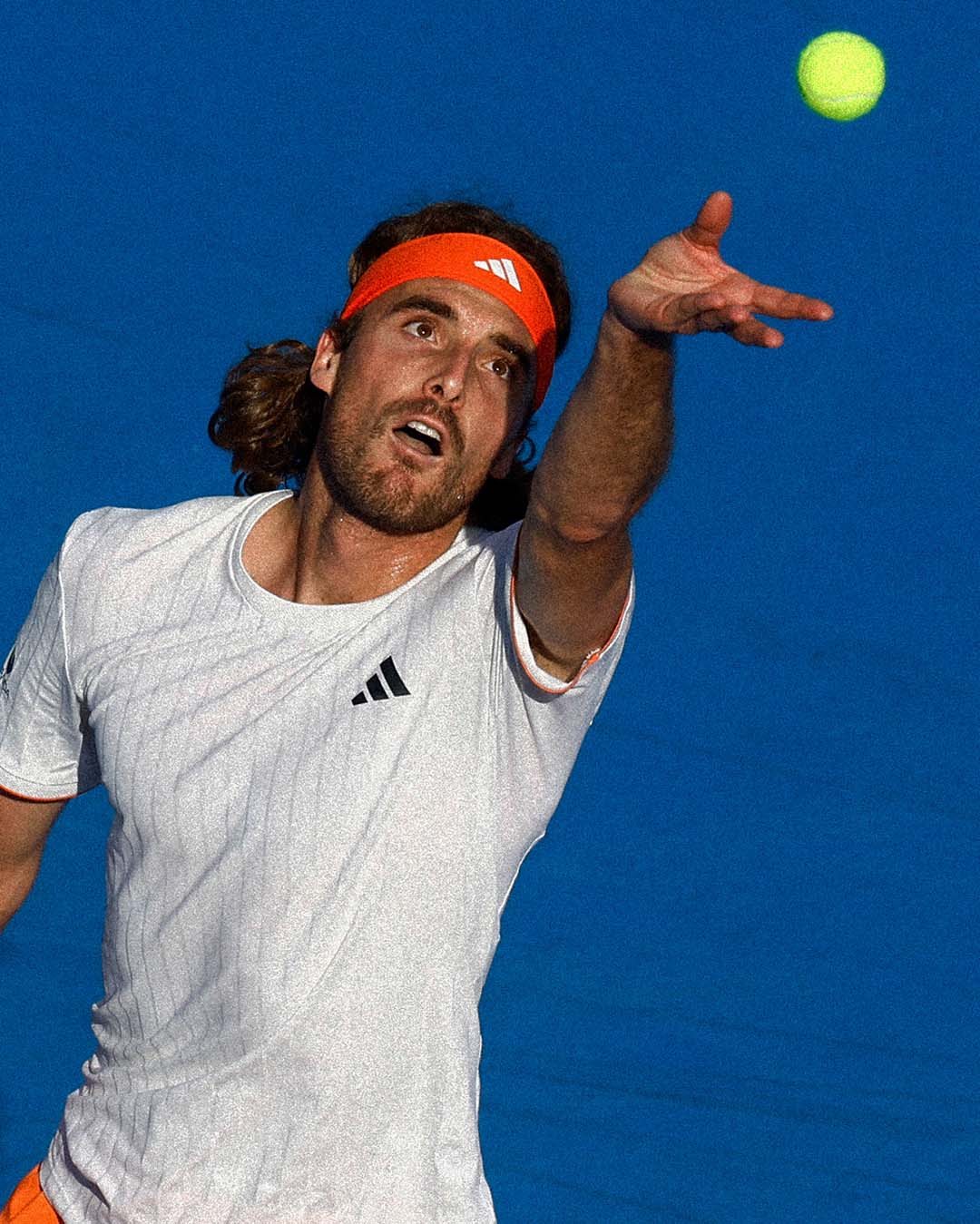

Stef find his form against Meddy in Doha this week. // Getty

Stef find his form against Meddy in Doha this week. // Getty

Here’s a measure of how far the mighty have fallen: A matchup between Stefanos Tsitsipas and Daniil Medvedev was, for many years, appointment viewing. Here was one of the most charged rivalries on tour, between two rising superstars who entered tennis legend with their 2018 Miami Open scuffle. Or, as I will always remember it, the “Shut Your Fuck Up” summit, a day of absolutely unforgettable language hurled across the net. See also: “small kid who doesn’t know how to fight.” (Should you want a hat memorializing that day, we have got you covered.)

The Tsitsipas-Medvedev beef continued to simmer over the years, as they commented on their strange relationship (“definitely not friends”), carped about the other’s style of play (“boring”), and played a few classics, some of which involved on-court oddities. To wit: the “sting operation” during their 2022 Australian Open semifinal, where a Greek-speaking off-duty umpire lurked in the tunnel to bust the Tsitsipas family for illegal coaching from the player’s box. I loved watching them play. It seemed like a recipe for weirdness. And they were clearly poised to inherit the tour.

Fast-forward to February 2026, there’s a Medvedev-Tsitsipas match in Doha, and I forgot it was even happening, had to catch a replay. Each player has fallen from past glory and has been left wandering the desolate landscape of the tour. The Medvedev downfall is well-documented, though his recent tennis ball rant deserves a brief mention, before we shift to contemplating the demise of Tsitsipas. He entered 2025 still ranked No. 11 in the world, still clinging to his former top 10 stature. Here are the good things in the 2025 Stefanos Tsitsipas tennis season: won his first 500-level title in Dubai. As for the bad things: pretty much everything else. After mid-April, he did not win back-to-back matches for the rest of the season. He ended 22–20, having fallen to No. 34 in the world.

That’s the high-level story. The details are even grimmer. His primary struggle was with a chronic lower-back issue that had bothered him since the end of 2024. That loomed over his entire season. Then there was also the perennial issue of coaching. Longtime observers of the Tsitsipas family will have noted the queasy on-court relationship between Stefanos and his father-slash-coach, Apostolos. Aside from brief dalliances with Mark Philippousis and Dimitris Chatzinikolaou, Tsitsipas has relied only on his father for coaching. That’s why it was so refreshing when he announced his partnership with Goran Ivanisevic. The former Wimbledon champ, and highly successful coach of Novak Djokovic, was still in search of his first long-term client after splitting with the Serb in 2024 and attempting a doomed partnership with Elena Rybakina. On paper this collaboration would have been an excellent fit for both player and coach. They said nice things about each other at the inception in May.

By July, it had blown up. Tsitsipas retired in the first round of Wimbledon due to his back and revealed that he was still deciding “whether I want to keep going or not,” referring to his career in professional tennis. After that loss, Ivanisevic appeared to go on a miniature media tour to flame his own player, with a splendor that is simply no longer seen in their professional realm. “He needs to fix his back and get physically fit because physically—he’s a disaster. I can’t understand how a player of his level can be so unfit. After that, he can think about playing tennis again,” Ivanisevic told CLAY. “He has to find a solution for his back issue. I was shocked. I’ve never seen such a poorly prepared player in my life,” he said in an interview with SportKlub. “Me, at my age and with this bad knee, I’m three times in better shape than him. I’m not sure what he was doing in the previous 12 months, but his current shape is very poor.” He is one of the best quotes in the tennis world, but that’s not actually a desirable quality in a coach.

Before the end of the month they had officially split. The partnership lasted just two tournaments, and according to Tsitsipas’ public statement, it was a “brief but an intense experience and a truly valuable chapter in my journey.” Elsewhere, in an interview with Greek outlet SDNA, Tsitsipas said, without naming anyone in particular, that it was “very difficult to have dictators and people who speak negatively” in his team. He got back together with his first coach: his dad. Hard to cheer on that particular reunion. After a second-round loss at the US Open, Tsitsipas could not walk for two days. He then shut down his season. While dealing with his injury, he felt like “I was just an observer of tennis and the ATP Tour, rather than an active participant,” he said in an interview with Bolavip. Entering the 2026 season, the back injury still required management.

All that context makes Tsitsipas’ straightforward 6–3, 6–4 win over Medvedev on Wednesday in Doha all the more miraculous. He moved well, closed out points at the net, and notched his only victory over a top 20 player since July 2024, at the Paris Olympics. (We’re already at the next damn Olympics! That’s how long it took.) Conversely, this must be a devastating development for Medvedev, who had won the last three matches in their head-to-head and had been in okay form this year, compared with his own abysmal 2025. Yet there he was, falling to a familiar rival, as neither player could muster tennis that looked remotely capable of winning them the Slams they once looked poised to rack up. Life goes on, but no one wants to lose the battle of the washed.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

The Overthinker

The Overthinker

The Overthinker

For the past three seasons, it's been more struggle than smooth sailing for Iga Swiatek.

For the past three seasons, it's been more struggle than smooth sailing for Iga Swiatek.

By Owen Lewis

February 19, 2026

Iga looks for answers in Doha last week. // Getty

Iga looks for answers in Doha last week. // Getty

Let’s get this out of the way at the top: Iga Swiatek has six majors and 125 weeks at No. 1 at 24 years old, is iconic for brutalizing opponents (she lost all of 10 points in the fourth round of Roland-Garros in 2024), and is historically great on clay. Barring Aryna Sabalenka suddenly becoming automatic in major finals (lol) or Coco Gauff beginning to win majors in bunches (we’re just a serve and a forehand away), Swiatek will go down as the player of her generation. Last year, Swiatek completed an annihilating Wimbledon victory by winning her last three sets of the tournament 6–0. Any problem with Swiatek’s tennis is both relative and, let’s be honest, a convenient way to spin what is really just something interesting to talk about: When Swiatek has struggled—and she has struggled a lot, especially in the last year and change—the struggles have felt like they were about her identity as a player and her happiness as much as her results. It’s even felt like Swiatek has done more struggling than smooth sailing for the past three seasons, which feels ridiculous to type because she has done so much smooth sailing. And yet…

Swiatek just lost to Maria Sakkari from a set up in Qatar, which ended her career-long never-lost-from-a-set-up-at-a-1000-level-event streak. If you watched Swiatek play Sakkari anytime after 2021, you also probably never thought Swiatek would lose to her again. Upsets happen and streaks end. But this loss came on the heels of a rather abrupt 7–5, 6–1 defeat to Elena Rybakina at the Australian Open. And a loss to Rybakina at the WTA Finals, in which Swiatek won only one game in the last two sets. And a 6–1, 6–2 loss to Jasmine Paolini in China. And sets she lost 6–0 to Emma Navarro and Belinda Bencic. And a streak of eight sets and counting she’s lost to Coco Gauff, whom Swiatek won 11 of her first 12 matches against. She isn’t regularly going deep enough in tournaments to get to Aryna Sabalenka, so nobody really knows where that rivalry stands. It feels like most top players, who lived in fear of Swiatek when she crushed the tour in 2022, now relish playing her and produce their best tennis accordingly. Swiatek destroyed the field at Wimbledon last year and followed that triumph with titles in Cincinnati and Korea, a hot streak ended the wintriest six months of Swiatek’s career to date. Now summer seems over once again. So let’s talk about this.

Iga Swiatek wants to win tennis matches so badly. It’s why her routines are intense enough to be a little bit uncomfortable, whether that’s her jumping by the net during the coin toss, her religious consistency in taking bathroom breaks after the first sets of her matches, or the way she looks like she is rapidly cycling through the five stages of grief when a match starts to slide away from her. It’s why when she does win, it’s impossible to imagine another outcome because it feels so natural. It’s why she didn’t give Amanda Anisimova a game in the Wimbledon final last year and found the suggestion that she could have insane. I think it’s why she used to try to distract opponents by waving her arms when they went to hit a putaway—unconsciously!—and had to try to train herself out of the habit once she realized she was doing it. It’s why she bounced a ball hard into the ground, skimming it close to a ballboy’s head, in the midst of losing to Mirra Andreeva at Indian Wells a few months before that. It’s why her statement afterward—sort of an apology, but mostly a long meditation on how fucking hard she was finding the whole tennis thing—felt more than a little bit tortured. It’s why she acknowledged in the statement that the realization she wouldn’t get a look at the No. 1 ranking for a while “deeply upset” her, which most players would not have admitted to being anything more than motivated by. (Almost a year later, Swiatek still isn’t sniffing the No. 1 spot.) It’s why Swiatek doesn’t get visible joy when her tennis excels in concert with her opponent’s, only satisfaction at the little successes and relief when she wins in the end.

It’s also, I’d posit, why Swiatek is not winning as many tennis matches as she’d like to right now. Swiatek is caught between styles, striving toward the varied and patient game with which she broke out in 2020, but trapped in the hyperaggressive baselining that saw her reign over the tour in subsequent seasons. Swiatek is one of the best movers on the WTA, capable of sliding into her shots from nearly any position. That defense can elicit errors from the best attackers. But lately, when she’s on the ropes, Swiatek abandons her defense entirely in favor of harder and harder ground strokes, which inevitably go awry. In errant hyperaggressive mode, Swiatek looks utterly miserable: aware of what she needs to do but incapable of doing it. (Hopefully she doesn’t make like Kylo Ren.) How many other godlike tennis players can we overthinkers relate to so closely?

This past week, I rewatched Swiatek’s first major final, a 6–4, 6–1 win over Sofia Kenin at Roland-Garros in 2020. Though just 19 years old back then, her patience astonishes. Her movement was already fantastic but was geared more toward setting trip wires for Kenin than ripping a winner from an improbable position. She was more than happy to spin defensive shots back, absolute in her confidence that Kenin would eventually miss. Some aggressive defense featured too, notably a backhand down the line that found the corner each time Kenin successfully yanked her outside the tramlines, though they were hit more out of necessity than aggression. She conjured a few backhand drop shots—not as a load-bearing part of her strategy, just one more way to win points—that all worked. At 15–30 down in the second set, she approached the net behind an inside-out forehand that was decent but certainly vulnerable to the pass, and clipped a confident volley winner. Yet she was still the aggressor, hitting 24 winners to Kenin’s 10! Swiatek accomplished all this without ever playing too hurriedly, and won in barely an hour.

Swiatek and the tour have changed so much in the past five years and change that it’s hard to blame her for being in a hurry now. She hired Tomasz Wiktorowski as her coach in the 2021 offseason, then promptly won 37 matches in a row in 2022. Her standard baseline game cut through the field so easily that those spontaneous drop shots and net rushes no longer seemed necessary. But the tour proceeded to get significantly stronger in the coming years. While Swiatek’s defense could have returned a lot of power players’ blasts, she elected to try to match their offense rather than accept the role of chaser. She’s had plenty of success but has lost the game with which she broke out in the process. In late 2024, Swiatek parted with Wiktorowski and hired Wim Fissette, who wanted to bring that old game back. Despite some early promising signs, the search continues. At the Australian Open last month, I asked Swiatek how she felt about her game relative to when she exited the tournament last year.

“This year we didn’t manage to, like, completely close the stuff that we wanted to change in the preseason. It just got a bit longer for me to change some stuff, you know. So this year I felt like I also needed to work on it during the tournament, and that’s why maybe, I don’t know, I felt like I played, like, tiny bit worse,” Swiatek said. She added that she didn’t think that mattered, but come on, making the quarterfinals while actively tinkering with your game beyond the usual match-to-match tweaks deserves a trophy of its own. It’s rare that anybody’s tennis is exactly where they want it to be, but Swiatek’s doesn’t feel particularly close.

Swiatek’s plight is fascinating—she’s in search of a brand of tennis that once was natural but has been dormant for long enough to become inaccessible. It’s still in her somewhere. In the second set of her Roland-Garros semifinal with Sabalenka last year, Swiatek hit perfectly weighted drop shots on consecutive points, from compromised positions (and right after consistent Iga skeptic Chris Evert shaded her touch). Can we reunite with parts of ourselves that are lost to time if we work hard enough to dig them up? In the late years of his career, Andy Murray retained many of his scrambling abilities but could not, try as I’m sure he did, compensate for what he lost by just banging the damn ball. It’s hard, so hard, to grant yourself mental permission to deviate from the strategy that has served you well for years. Swiatek is at least trying to deviate back to a software she’s implemented before, but that doesn’t seem to be any easier.

The match point from the Sakkari loss will stick with me more than the defeat itself. Swiatek had the point in her pocket. She ripped a forehand down the line that Sakkari could only reach with a desperate, floaty slice backhand at the very end of her range. Swiatek charged the net to clean up. Had she run straight at the ball, she’d have been there in plenty of time to spike it into the ground for a winner. But she ran around the ball instead, intent on hitting a forehand volley, and the ball dipped below the height of the net by just enough that Swiatek couldn’t clear it. I imagined her younger self racing along a more direct path to hit the correct shot, secure in her identity as a player and unburdened by all the pressure to follow. Wanting something too badly usually precludes you from getting it, so perhaps the way forward for Swiatek is to crave winning a little bit less. But then, that would deviate from her identity as well.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

The Top Ten For Vicky Mboko

The Whole Deal

The Whole Deal

Vicky Mboko's unique strength? Winning tennis matches.

Vicky Mboko's unique strength? Winning tennis matches.

By Giri Nathan

February 13, 2026

The youngster Vicky Mboko in Doha this week. // Getty

The youngster Vicky Mboko in Doha this week. // Getty

When watching a new player, it’s usually not that hard to determine Their Whole Deal. Tennis players usually find a way to play that emphasizes certain weapons and masks certain deficiencies. And with young players in particular, you tend to see a large gulf between the things they’re good at and the things they’re bad at. They are rarely so mysterious. But I must confess that I watched a whole lot of Victoria Mboko last season and ended the year still unsure what sort of tennis player she was, just aware that she was uncannily good at winning close matches. And now that I have watched much more Mboko this week—two scintillating top 10 wins in Doha over Mirra Andreeva and Elena Rybakina—I remain as confused as ever.

Let’s at least attempt the exercise. Weakness: a little bit of inconsistency on the forehand, maybe. Strengths: the remainder of tennis? The reason I had difficulty pinning down her game is because it incorporates so many different elements. Her movement is superb, as is her ball-striking, as is her feel. Depending on the match you catch, one of those aspects might be taking over, and the others receding. She never looks to be out of any point, and she can turn it around in an instant. To watch her for an hour is to see her take over rallies in any number of ways: defensive squash shots, a driving forehand slice, topspin lobs, an inside-out backhand ripper. She can counterpunch or play the aggressor. She can play with shape, or she can slap it. She can take big risks, like stepping well inside the baseline to return the imposing Rybakina serve—and then cracking it, over and over, like few players ever have.

There are players in recent history who have accomplished more on court by her age, but there have not been many with such a well-rounded skill set. I’m banking on this Canadian eventually winning the biggest titles in the sport. I suppose that’s not a terribly bold statement to make about a player who first broke out in August of last year and now already has a 1000 title, a 250 title, and a 500 runner-up to show for it; a player who has now already four wins over top 10 players. She’ll be among them soon enough. Depending on how the rest of the Doha tournament goes, next week she will either enter the top 10 or linger just one spot outside it. The speed of her ascent has been astonishing. After winning Montreal in August, she went on a four-match losing skid. After that point, she has gone 20–4.

I was recently asked in an interview which of the rising teenagers on tour would have the best future. At the time, it felt impossible to argue with Mirra Andreeva’s résumé, so I picked her. She’d been performing well at the majors since she was 15 years old. She picked up back-to-back 1000 titles last season. And moreover she was a full year younger than Mboko, whom she had also defeated (albeit in an injured state) in the Adelaide final in January. But their more recent encounter in Doha, which Mboko won in a third-set tiebreak after erasing one match point, has made me far less secure in that answer. Mboko has a bit more firepower. This was, ideally, a preview of one of the great rivalries over the next decade, now tied at one win apiece. I now think that rivalry will be very evenly split.

From there, Mboko went on to upset the recent Australian Open champion, Elena Rybakina, in the quarterfinal. She did it by fearlessly attacking the best serve on tour, breaking it six times. I don’t know if it’s just the echoey acoustics on the court, but this looked like some of the hardest ball-striking I’ve seen in some time and will probably wind up one of the highest-level matches of the season. And any 19-year-old who can step up and match Rybakina’s power without getting overwhelmed is on a fine trajectory. The players have now split their four matchups to date.

In her brief tour-level career, Mboko has often appeared resistant to scoreboard pressure, and she won both these matches despite having trailed by a break in the deciding set. “Yeah, I feel like there’s been so many times where I’m down a match point, or the opponent has a match point, but I don’t really think much of it,” the Canadian said in press after defeating Andreeva. “I just think of it as any other point in the match.” Very easy to say, harder to exemplify that perfect equanimous tennis mind, but that she has: After turning these two matches around, Mboko is now 7–1 in three-setters this season. If they manage to come up with new ways to be good at tennis, I’m sure she’ll be promptly adding them to her never-ending list.

On Friday, she routined Jelena Ostapenko—last year’s Doha runner-up—to qualify for her second 1000-level final. Her reward was that most precious and scarce WTA commodity: a gracious hug from a freshly defeated ‘Penko. Who doesn’t love Mboko?

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Love Bomb

Love Bomb

Love Bomb

A mysterious call in 1984 robbed Ivan Lendl of a potential double bagel in Rotterdam.

A mysterious call in 1984 robbed Ivan Lendl of a potential double bagel in Rotterdam.

By Simon Cambers

February 13, 2026

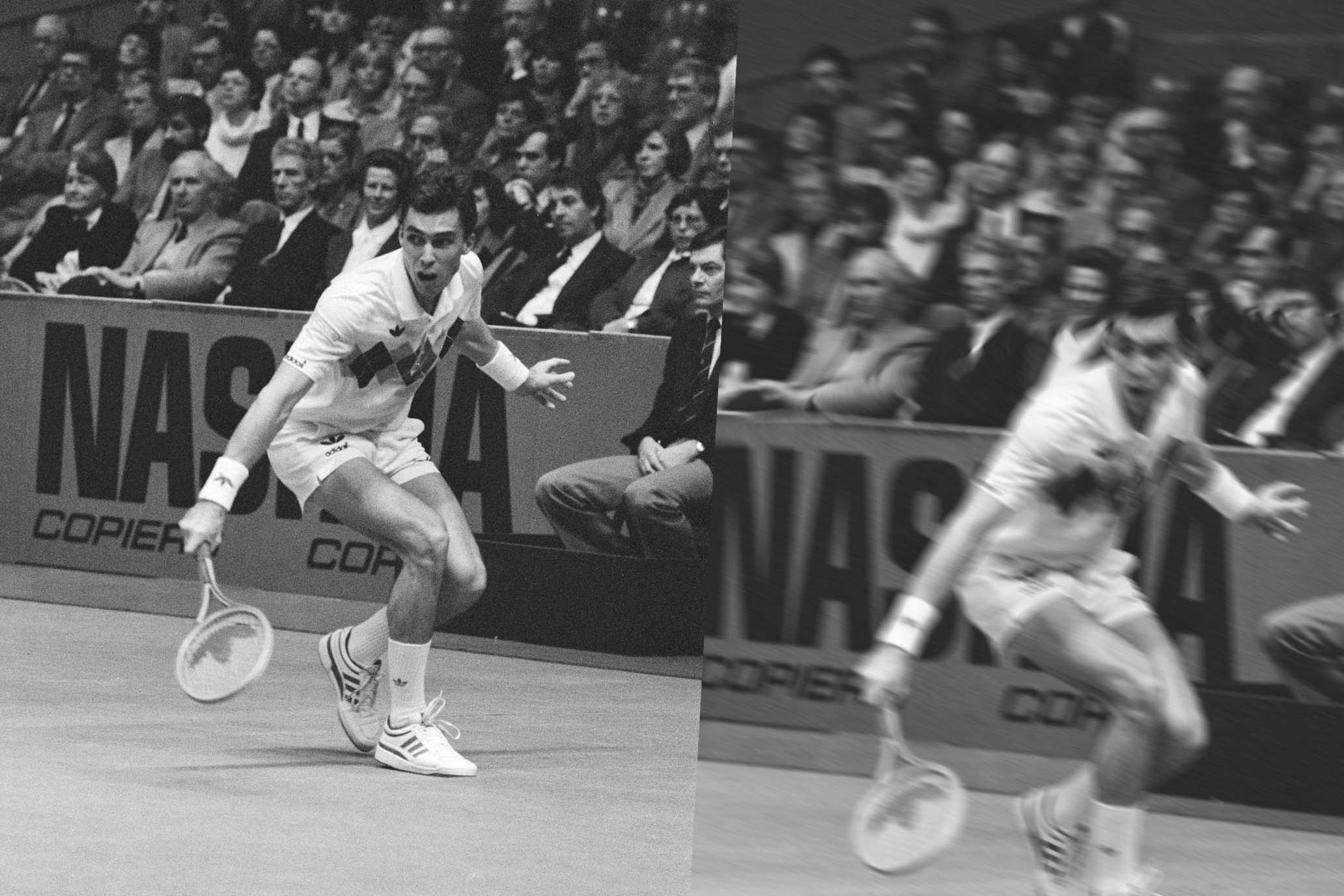

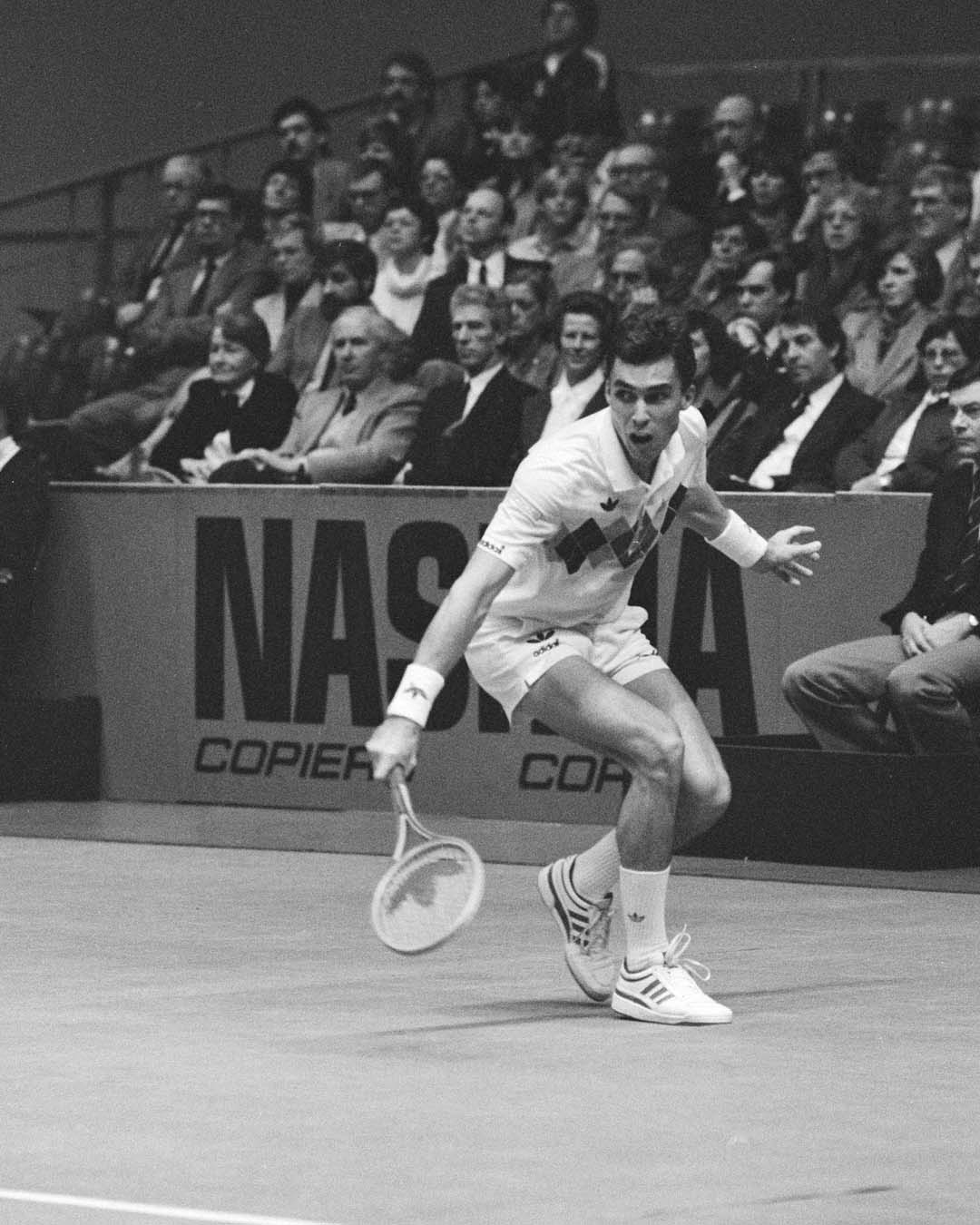

Ivan Lendl plays Jimmy Connors during the Rotterdam final in '84, before the match was suspended. // Alamy

Ivan Lendl plays Jimmy Connors during the Rotterdam final in '84, before the match was suspended. // Alamy

The ABN/AMRO World Tennis Tournament in Rotterdam has always been one of the most prestigious indoor stops on the ATP Tour, dating back to 1972, when the great Arthur Ashe beat the flying Dutchman, Tom Okker, in the inaugural final. Its honor roll reads like a who’s who of men’s tennis; from Ashe to Bjorn Borg and Jimmy Connors; from Stefan Edberg and Boris Becker to Roger Federer, Jannik Sinner, and, last year, Carlos Alcaraz.

But Rotterdam’s Ahoy Arena is also the venue for one of the more bizarre moments in ATP Tour history and one of the great stories (and myths). In the 1984 final, Ivan Lendl was leading Jimmy Connors 6–0, 1–0, seemingly cruising to another title, when the match was interrupted. “Don’t panic,” came the voice of Nico Dijkhuizen over the loudspeaker, explaining that there was a bomb threat. “Leave the hall calmly and quietly.” The same words were carried on the scoreboard.

The threat had reportedly come from an anti-capitalist, but after a quick check, it was clear it was a hoax, and the green light was given for the match to resume. The fans filed back into the stadium, maybe hoping for a famous Connors comeback, while probably expecting Lendl to complete the demolition job. But the match never restarted.

“By the time the spectators were allowed back in, Connors and Lendl were already together on a private jet at the nearby Zestienhoven Airport,” former pro Marcella Mesker told The Second Serve this week. “They were taking off for the United States, where they were scheduled to play their next tournament.”

According to a New York Times report at the time, Connors had been willing to resume, but Lendl felt it unsafe. The pair were each awarded runners-up ranking points, but Lendl asked that the prize money—$50,000 for the winner and $25,000 for the runner-up—be put into a vault until the match could be completed. Mesker, a top singles and doubles player and now a leading commentator for Dutch broadcaster NOS, confirmed this week that Lendl did make that request but said Connors did not agree. “Lendl did like his money,” she said. “It’s a bit unknown what happened. But the story here is that they split it.”

Considering that Connors still holds the record for the most titles won on the ATP Tour, with 109, and that Lendl sits fourth on the list with 94, giving up the chance to win another title would doubtless not have come easy to either man. Years later, Peter Fleming, half of one of the greatest doubles teams in history alongside John McEnroe, told the story of the final on Sky TV and had a unique take on the incident. “If you ask Lendl, even to this day, he still thinks someone from Jimmy’s team made the phone call,” he said, tongue, perhaps, firmly in cheek.

If Lendl does still believe that, though, he is not saying so in public. “I remember the match,” he told The Second Serve this week. “It seemed like a serious situation, so we didn’t have any choice about continuing the match. But I would not have minded [doing so], since at the time, I was up a set and a break. We never finished the match, and I don’t know if they were ever able to determine what happened.” Connors did not respond.

Deprived of watching the completion of the final, the spectators were later given 15 guilders (about $6) as compensation. “And they did have the doubles to watch,” Mesker said. For the record, Kevin Curren and Wojtek Fibak won that one.

“It’s an iconic part of the history of the tournament,” Mesker said of the story. “It seems funny to us [that it comes up every now and again], because we all know it well.”

Lendl was, of course, one of the most ruthless players around, and being denied a double-bagel win over one of his greatest rivals would surely have rankled. However, his disappointment didn’t last long; a couple of months later, he beat Connors 6–0, 6–0 in Forest Hills and went on to win his first Grand Slam title that summer, at Roland-Garros, when he came from two sets down to beat McEnroe in the final.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

A Future For France

A Future For France

A Future For France

Moise Kouame is the young hope of French tennis.

Moise Kouame is the young hope of French tennis.

By Giri Nathan

February 6, 2026

The youngster Moise Kouame in Montpellier this week. // Getty

The youngster Moise Kouame in Montpellier this week. // Getty

Hyping a young prospect never ends well for me. But as far as the men’s tour is concerned, it’s a good time to peer far into the future. With nine straight Slams won by either Carlos Alcaraz or Jannik Sinner, and—with respect to Novak Djokovic—no sign that the pattern will break anytime soon, many fans are rooting around to figure out who their true challengers will be. They are just 22 and 24. I don’t think they will be troubled by any of their direct contemporaries. I’ve watched Ben Shelton lose 22 straight sets to Sinner, and I can’t be convinced that the gap is closing. As for the even younger players, the 19-year-old ball-striking prodigy Joao Fonseca lags behind in terms of movement (and, currently, health). While 20-year-old Learner Tien has endless touch and guile, will he ever have enough point-ending power? Many seek the Novak Djokovic figure who will complicate the Sincaraz reign, and while I’m not sure that the future will rhyme with the past so neatly, it’s at least worth noting that Novak is a full six years younger than Roger Federer. So maybe the promised one is still a long way out.

Which is partially why I welcome the buzz around a player six years younger than Carlitos: the French 16-year-old Moise Kouame, who this week made it into the main draw in Montpellier. On those loud blue-and-pink hard courts, Kouame cut a striking figure, clad in purples. He stands 6-foot-3, with speed, balance, and elegant technique. Despite his age he appears to already have the legs to tolerate some grindy pro-level rallies, and the sudden power to find a winner when he sees the opening. He says he looks up to Novak Djokovic and Jannik Sinner. While it’s way too early to tell, his play style tempts me to place him in that same lineage. I can envision a baseline crusher very hard to hurt on either wing.

In the qualifying rounds, Kouame played two difficult three-setters, which were his first two wins over players ranked inside the top 200. These weren’t the prettiest matches, but they secured a historic result. There’s little recent precedent for a kid this age making it into the main draw of an ATP tournament. Kouame became the sixth-youngest qualifier for a tour event since 2000. The only names ahead of him are Richard Gasquet (twice), Ryan Harrison, Rafael Nadal, and Rudolf Molleker (a 25-year-old now ranked No. 442). So you never know what will happen. But perhaps he stands to benefit from having one of those men, the recently retired Gasquet, as his coach. Ivan Ljubicic, another former great, now director at the French Tennis Federation, has been singing Kouame’s praises for a long time. It’s clear that France thinks he’s their future.

Heading into the main draw at Montpellier, Kouame had won 12 consecutive matches, in ITFs and in ATP qualifying. In his first main-draw match on Wednesday he faced world No. 56 Alexander Kovacevic, who was, by a huge margin, the highest-ranked opponent he had ever taken on. Kouame played a superb first set, lost his way in the second, and put up a good fight for his life at the end of the third, before losing. The flaws are the ones you might expect from a young player—conditioning issues and a serve that needs tinkering—but the foundation is already astonishingly good, and the highs are incredibly high. Perhaps by the end of 2026 we could see him competing at the Challenger level regularly. Sinner and Alcaraz were winning Challenger titles at 17. Can Kouame stay on that trajectory? The successes of this week will bump him up to just outside the top 500. There’s still a very long way to climb.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Film Review: Islands

Ominous Strings

Ominous Strings

Film Review: Jan-Ole Gerster’s Islands

Film Review: Jan-Ole Gerster’s Islands

By Patrick J. Sauer

February 6, 2026

A still from Islands.

A still from Islands.

It was, as native New Yorkers say, mad brick outside, so I decided to escape the Brooklyn tundra by partaking in some Canary Island tennis. All it required was a subway ride and a willingness to commit mind-over-frozen-matter while settling in for Islands, the new English-language movie from German director Jan-Ole Gerster. Set in the Spanish archipelago, specifically Fuerteventura, it opens on Tom, a local sun-dappled mid-tier resort tennis pro, passed out in the dunes somewhere near where he drunkenly abandoned his car for whatever after-hours was supposed to deliver. He isn’t sleeping off a huge bender, either. Tom’s routine of hungover lessons, midday hidden Scotch bottle bracers, and evening post-session-beers-into-late-night-vodka-shot-pumping, line-bumping client-humping has more or less become his life.

Tom (Sam Riley, best known as enigmatic, doomed Joy Division frontman Ian Curtis in 2007’s Control) isn’t motivated to change much, even if he doesn’t seem to buy into the constant tourist avowal that he’s got it made in the paradisiacal shade. He’s in a rut, paradoxically kick-started by the game that brought him there. A shoulder injury thwarted a promising professional career, but thanks to a reliable big serve, he beat a vacationing Rafa Nadal in an impromptu “can you get five of 10 past El Matador?” challenge. It’s the story of his nickname, Ace—which we will be using henceforth—one he’s sick of hearing, but one that, if he doesn’t soon shake off the morning shakes, will be his legacy.

To paraphrase English poet John Donne, “No man is an island, not even in the Canaries.” Enter Anne (Stacy Martin), an icy blonde looking to get her passive, lonely 8-year-old son Anton (Dylan Torrell) moving around out on the courts. As luck would have it, Ace is really great with kids, which means more quality time with the woman he swears he’s seen before. Anne and her unctuous, arrogant, “calls everyone bro” Brit husband, Dave (Jack Farthing), are slumming it among the hordes at an all-you-can-eat-buffet getaway spot with the idea to stabilize their crumbling marriage foundation via a weeklong getaway. Always a good plan, especially when a hot tennis pro who’s always down to go to a second location is added to the mix.

Ace is clearly intrigued by Anne and, upon Dave’s whining about the view-of-the-dumpsters accommodations, upgrades their room for free. This leads to dinner, as the slowest of sunburns takes over Islands and it becomes a Hitchcockian character study. On his one day off, Ace takes the family on an excursion to the gorgeous non-touristy lava caves and crashing-wave beaches—virtuoso cinematographer Juan Sarmiento had me absolutely pining for the Atlantic Ocean—on the other side of Fuerteventura, a spot he sheepishly admits to Anne he hasn’t visited in years. (Yep, and on the sly, Ace rubs lotion on her naked back.) He even brings Anton to take a camel ride at a farm owned by his friend Raik (Ahmed Boulane), who, in addition to being the guy who drags the Rafa story out of Ace, is constantly having to hunt down one of their lumbering beasts, who wanders off whenever there are volcanic tremors from the nearby island of Lanzarote. It’s a full day, one that should’ve ended when Anton and Anne went to bed but carries on with Dave well into the wee hours at a loud all-night techno club, Waikiki. The off-the-chain lightweight’s intentions are clear: bottle service, selfies, sexy dance partners, and to see where it goes until daybreak. What’s not clear is where the hell Dave ended up.

When Ace rouses to life on a poolside lounger the next morning, Anne is already in full panic mode trying to find her wayward partner. At first, the local policia assume another honey-rum-soaked idiot ended up in a stranger’s bed, but when Dave’s Hawaiian shirt (of course) turns up on shore, an all-out criminal investigation, complete with helicopter searches, gets underway. Gruff, no-bullshit Inspector Mazo (Ramiro Blas) comes in from the mainland, and the clues, coincidences, and convoluted timelines start adding up, all pointing toward Ace’s Ripley-esque infatuation. In fine Patricia Highsmith form, Gerster keeps the sociopathy at arm’s length, just enough for Ace to question his belief in Anne, drifting through life on Tinto de Verano bubbles, and if Dave’s dead, even at her murderous hands, whether they’re going to fuck.

I don’t want to give much more away, other than to say there’s a jaw-dropping moment with the wayward camel that brilliantly resets the movie, sending Ace off on a boozy exorcism of Nadal’s ghost. Unlike so many half-baked, phoned-in streaming thrillers, Islands isn’t constructed around illogical arbitrary twists. It methodically builds to a satisfying conclusion, even if not quite everything works in full.

Visually, our femme fatale commands the screen, but as a human character, Anne is underwritten, even if somewhat mysterious by necessity. As for Anton, after setting the wheels in motion, he gets stowed away and forgotten for a big middle chunk in the Kid’s Club. (Points for parental verisimilitude, I suppose.) And in the early going, the volcano metaphor is laid on thick, with Dave asking Ace, “Is it gonna erupt?” à la tempers, marriages, cuckolds, penises, and maybe, with a homicidal visitor, Fuerteventura itself. However, these are mild critiques as Ace’s response, “You never know,” captures what Islands does so well, including being a rare film that walks it off with a perfect last line.

Ace’s Islands unraveling makes for a bewitching balmy noir, where nothing—or everything—is as it seems. It definitely satiated my wintry need for sweltering tropical climes backed by ominous strings. Which, come to think of it, would make for a great sequel title if ever Ace goes looking for Anne again.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Elena Rybakina Summons the Ghosts

Back in a Major Groove

Back in a Major Groove

In the Australian Open final, Elena Rybakina summoned old ghosts.

In the Australian Open final, Elena Rybakina summoned old ghosts.

By Carole Bouchard

January 31, 2026

A victory that will haunt Aryna Sabalenka. // Getty

A victory that will haunt Aryna Sabalenka. // Getty

It was a blink-and-you-missed-it situation. Blink, and you missed Elina Rybakina crumbling from one set and 4–4 up to one set all and 3–0 down. Then blink, and you missed Aryna Sabalenka collapsing from 3–0 up in that third set to lose a second Australian Open final in a row and so a third Grand Slam final in the last four she played. Blink, and you also missed Stefano Vukov, Rybakina’s coach, who was banned for a year, being celebrated during the trophy ceremony.

In that remake of the 2023 Australian Open final, Rybakina ended up getting revenge on Sabalenka in a three-setter in which neither player played their best at the same time, resulting in an error-laden performance. Both being in the same lane of “everything you hit, I can hit it harder” kind of tennis, you knew you wouldn’t get a lot of rallies. But in 2023, their final had also shown that “go big or go home tennis” could find its own version of being both entertaining and steady. This time, not so much.

Yet the third set’s drama made up for the up-and-down nature of that final. It was tough to imagine Rybakina adding a second Grand Slam title to her résumé after Wimbledon 2022, when she started to spread unforced errors all over that Rod Laver Arena as Sabalenka seemed to sprint toward a fifth Grand Slam title. The world No.1 was proving how many more options she had built into her game against an opponent whose A game is lethal, as seen in a flawless first set, but left on its own when things go south. But Rybakina showed more guts in the money time, banking on her ability to go for her shots. And it delivered: The backhand down the line started to fire up again, the forehand-to-forehand battle turned in her favor, and that service came clutch at last. Rybakina’s forever-cool face won against Sabalenka’s forever-on-the-edge look.

Rybakina confirms the feeling of the end of 2025 when she beat Sabalenka already to clinch the WTA Finals title: She’s getting that groove back and has learned consistency since 2022. The new Australian Open champion became the first female player since Naomi Osaka in 2019 to go all the way after beating three top 10 players (Swiatek, Svitolina, Sabalenka). “They’re tough opponents, have great results, and for so long they have been at the top and stable,” Rybakina said. “I’m happy that now I’m getting back to this level, and hopefully I can be stable again throughout the whole season and keep on showing great tennis, good results. It’s a lot of tough matches I had here. Yeah, I’m glad I could manage to take the opportunities I had and win in the end.”

Is she a different player today? No. Has she improved her game in the same vein as Sabalenka? Absolutely not. Is she still the biggest hitter on that tour with an unmatched ability to hit winners from anywhere on the court? Totally. Is she getting closer to perfecting her game style enough to deliver it without a glitch in the biggest events? A resounding yes. With now 38 wins, she owns the most victories on tour since the end of Wimbledon. She can get unplayable, and it’s always mostly going to depend on her, which wasn’t a situation suited to her victim of the day.

It’s impossible not to think that Sabalenka’s 2025 ghosts came back to haunt her when she was on serve at 3–1 and then 3–3 in that third set. She had done everything right to get her hand on that final, and yet it derailed again. She couldn’t find a first serve (52 percent in that set), then rushed the rest and missed, so that in no time she had lost five games in a row, left aghast as, after Melbourne and Roland-Garros 2025, another Grand Slam final was slipping through her fingers. “It was really aggressive tennis, and in that moment she had nothing to lose, so she stepped in, and she played incredible points,” Sabalenka said. “Maybe I should have tried to be more aggressive on my serve, knowing I had a break and could put pressure on her, but she played incredibly. She made some winners. I made a couple of unforced errors. Of course, I have regrets. When you lead 3–love, and then it felt like in a few seconds it was 3–4…great tennis from her. Maybe not so smart for me. Today I’m a loser, maybe tomorrow I’m a winner, maybe again a loser. Hopefully not.”

Sabalenka has been the best player in the world by far for the past two years, but under the highest pressure in the biggest tournament, there’s this glitch that can land at any time. “I was really upset with myself, because once again, I had opportunities. But I feel like I played great. I was fighting. I did my best, and today she was a better player…. But level-wise and in the decisions I was making and my mentality, I think I made huge improvements and that I’m moving towards the right direction.”

Put in the same pressure cooker, Rybakina and her ice-cold demeanor have now won two majors out of three chances, and that cannot be a coincidence. Back on the wall, she figures out how to summon her A game, and that’s what Sabalenka figured out at the US Open but still can’t do on demand. After taking down both Swiatek and Sabalenka here, on the heels of that great end of 2025, Rybakina’s confidence is going to rise at a very dangerous high for the rest of the field. “I always believed that I could come back to the level I was. I think everyone thought I would never be in the final or even get a trophy again, but it’s all about the work. Of course, when you’re getting after some big wins against the top players, then you start to believe more and get more confident.” Warning received.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

The Happy Slam Is in a Funk

The Happy Slam Is in a Funk

The Happy Slam Is in a Funk

The vibes are a bit off at the Australian Open this year.

The vibes are a bit off at the Australian Open this year.

By Simon Cambers

January 30, 2026

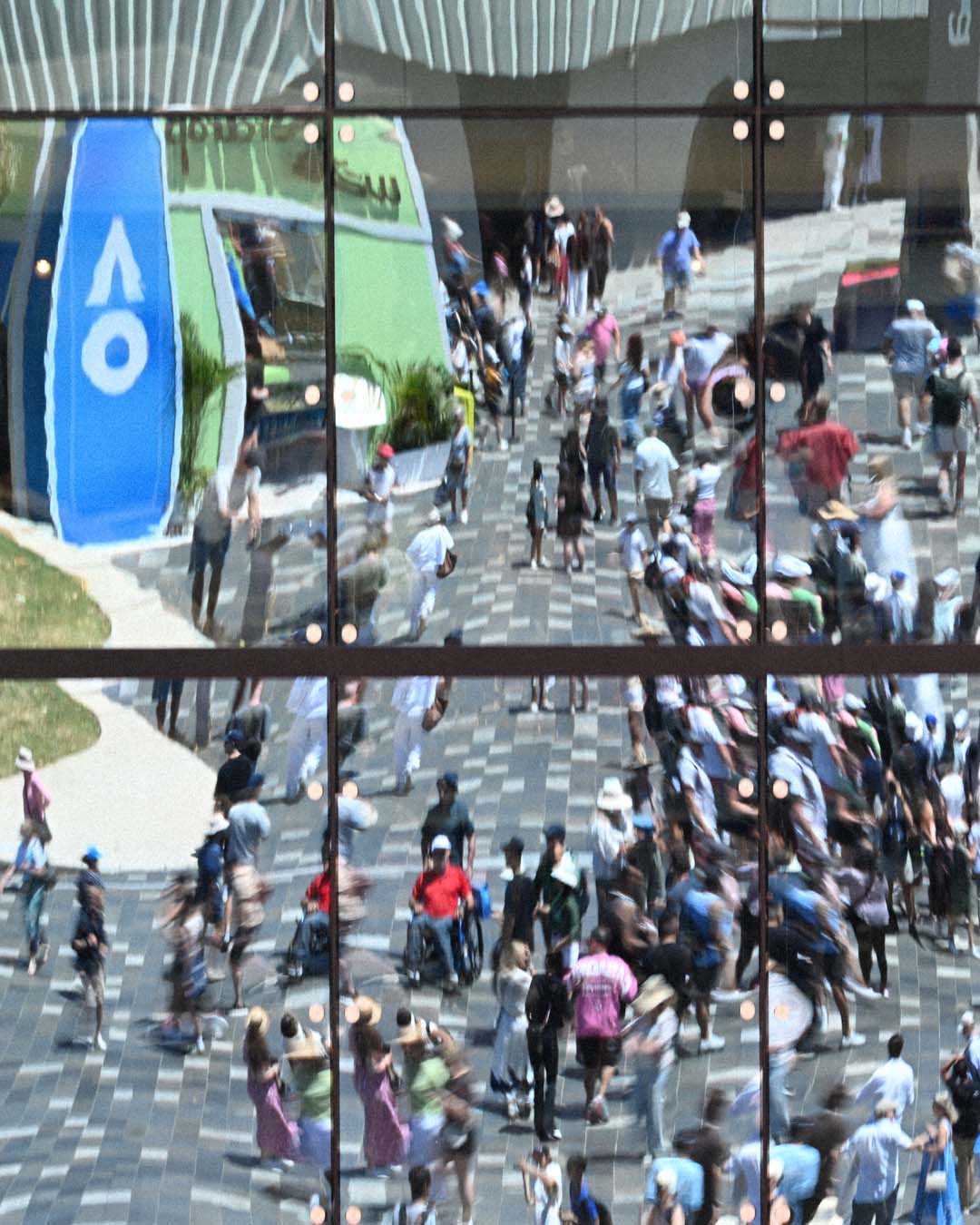

Fans sense a vibe shift at the usually Happy Slam. // Getty

Fans sense a vibe shift at the usually Happy Slam. // Getty

On the eve of this year’s Australian Open, Roger Federer, back at the tournament for the first time in six years to play in an exhibition as part of the opening ceremony, was reminded that he had coined the phrase “Happy Slam” for the first major of the year. That was back in 2007. Almost 20 years on, Federer said he was glad it had stuck and explained why he’d said it.

“It felt like a very normal thing to say because a lot of players, they’re happy to escape the European winter,” he said. “Finally you’re happy to maybe see the other players again [after a break], so it just feels very happy. The weather’s good, people are incredibly excited and pumped up about the Australian Open, we the players can feel that, the vibes are incredibly happy, nobody’s exhausted and tired [except for travel]. It stuck, and I’m happy it’s still the case because I still think the players are super happy to be here.”

As the 2026 edition heads toward its finale, the Happy Slam vibe remains relatively intact, although some of the gloss, it seems, has been rubbed off. While the increase in prize money across the board will doubtless have gone down well—total prize money is up to a record AUD $111.5 million ($78 million) from $96 million ($67 million) last year—around the fringes there has been some grumbling.

Not least from some of the players, irritated by what they see as the Big Brother feel of the Australian Open, where cameras are everywhere and privacy is limited. Coco Gauff, angry at her performance in losing to Elina Svitolina in the quarters, thought she was being considerate in not breaking racquets on the court. Instead, she smashed one in the corridor in the player areas, near the locker room. Unbeknown to her, it was immediately clipped up and sent around the world on social media.

“I feel like certain moments…they don’t need to broadcast,” Gauff said. Novak Djokovic, asked about the proliferation of cameras at Melbourne Park, went further. “I’m surprised that we have no cameras while we are taking [a] shower,” he said.

Of course, it’s a two-way street. Broadcasters, who are paying more and more each time for rights to show the tournament, want more bang for their buck, and behind-the-scenes footage fits the bill. Players might not like it, but the ever-increasing broadcast rights boost prize money. It will be interesting to see if there is any row-back on the cameras, but as Djokovic suggested: Don’t hold your breath.

Record crowds have flooded through the gates this year. Up to and including Friday, the main draw alone has seen more than one million people attend. It would have been more had it not been for a couple of days of 40-plus degrees Celsius (104F), when people wisely stayed away.

That’s been fueled by ground passes being on offer at very affordable prices (in week 1 they were around AUD$69 ($48). On the face of it, that’s a good thing, of course. Ordinary working people should be able to afford to come. And the result of that has been a huge buzz around the tournament. However, on several days, it was almost impossible to move around the grounds, so tightly packed was it.

And once on site, the prices were, well, pricey. Not as bad as at the US Open, as we outlined on the eve of the event. But still, fans were not happy at having to fork out AUD$14 ($10) for a small can of Asahi beer. Or up to AUD $25 ($12.70) for a Shake Shack burger.

Players do love coming to Melbourne, but the cumulative load on their bodies is also taking its toll. There have been six injury retirements to date in the men’s event, plus one walkover, and two retirements and one walkover in the women’s singles. Some, like Jack Draper and Holger Rune, didn’t make it here, and others, like Emma Raducanu, had shorter-than-usual preparation due to injury. It didn’t help that local heroes Nick Kyrgios and Thanasi Kokkinakis withdrew with injuries. Players are supposed to be arriving in rude health, but that’s not always possible.

The heat may also have been a factor in the unusually low number of exciting matches. Until the men’s semifinals, which were both incredible contests, the tournament was low on intrigue, low on shocks. Six of the top eight seeds made the semis in both events for the first time in the Open era, but with the exception of Stan Wawrinka, who even at 40 can still be relied upon to entertain, most matches felt a little flat. Playing in high temperatures is rarely conducive to great tennis.

There’s no question that players (and traveling media) are well-treated here. In addition to prize money, all players in the singles and doubles events (including qualifying) receive a check for AUD$10,000, along with a nice gift bag, to help with their travel and subsistence. Obviously the top players don’t need it, but it’s very useful for the lower-ranked players who come down to try to qualify, especially doubles players.

One thing to note, though, is the future of Craig Tiley. Tournament director since 2006 and CEO of Tennis Australia since 2013, Tiley is regularly thanked by the players for going above and beyond. However, Tiley is heavily rumored to be about to be named as the new CEO of the United States Tennis Association.

The weather may be great (largely) and the facilities second to none, but how Tennis Australia replaces him will go a long way to ensuring whether the Happy Slam remains a thing.