Postcard from Aix-en-Provence

Postcard from

Aix-en-Provence

Postcard from

Aix-en-Provence

Paris-based photographer Guillaume Tranchard checks in from Aix-en-Provence and the Open Aix Provence Crédit Agricole Challenger.

Paris-based photographer Guillaume Tranchard checks in from Aix-en-Provence and the Open Aix Provence Crédit Agricole Challenger.

Photography by Guillaume Tranchard

May 9, 2025

SIGN UP — YOU'RE ONLY AS GOOD AS YOUR SECOND SERVE.

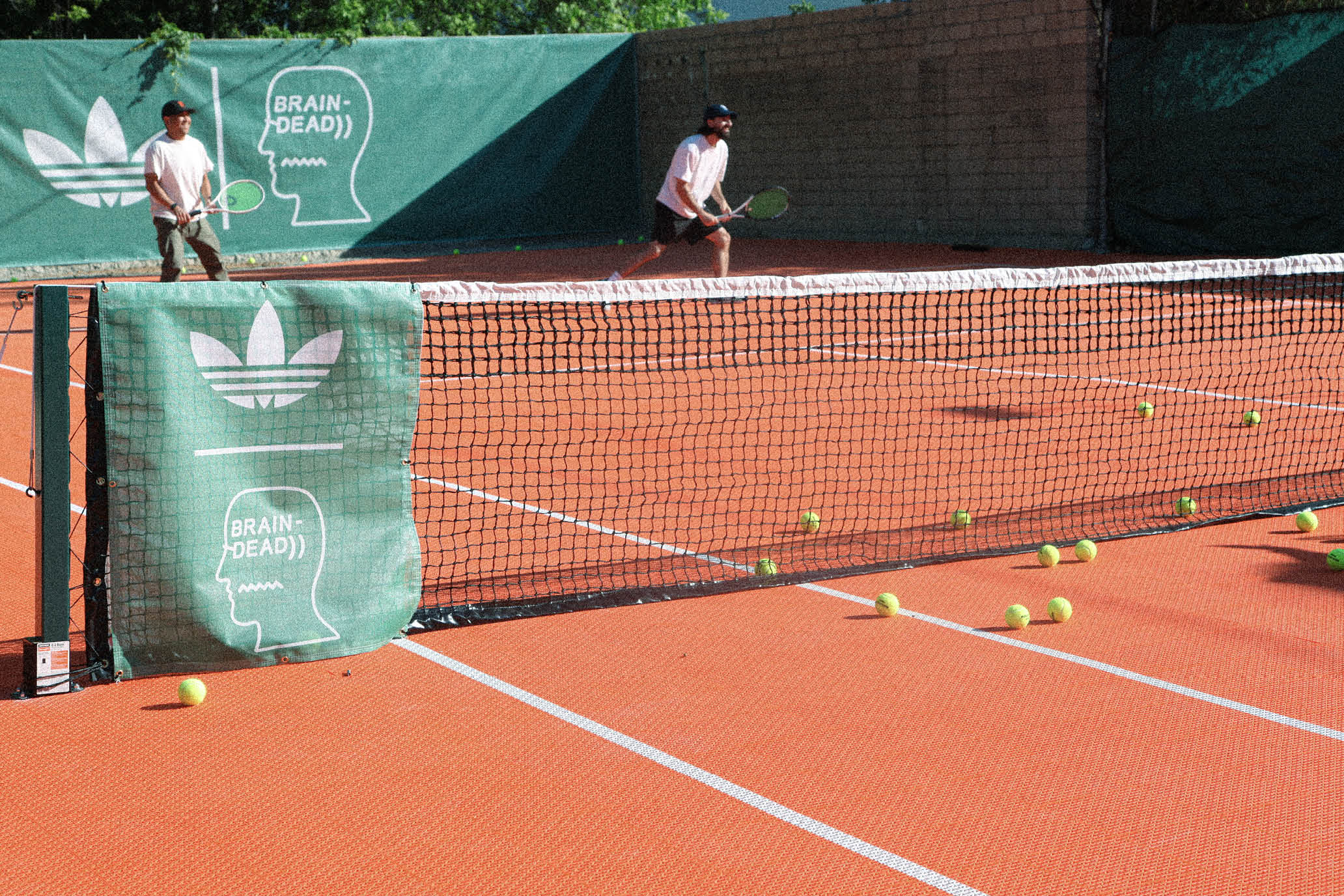

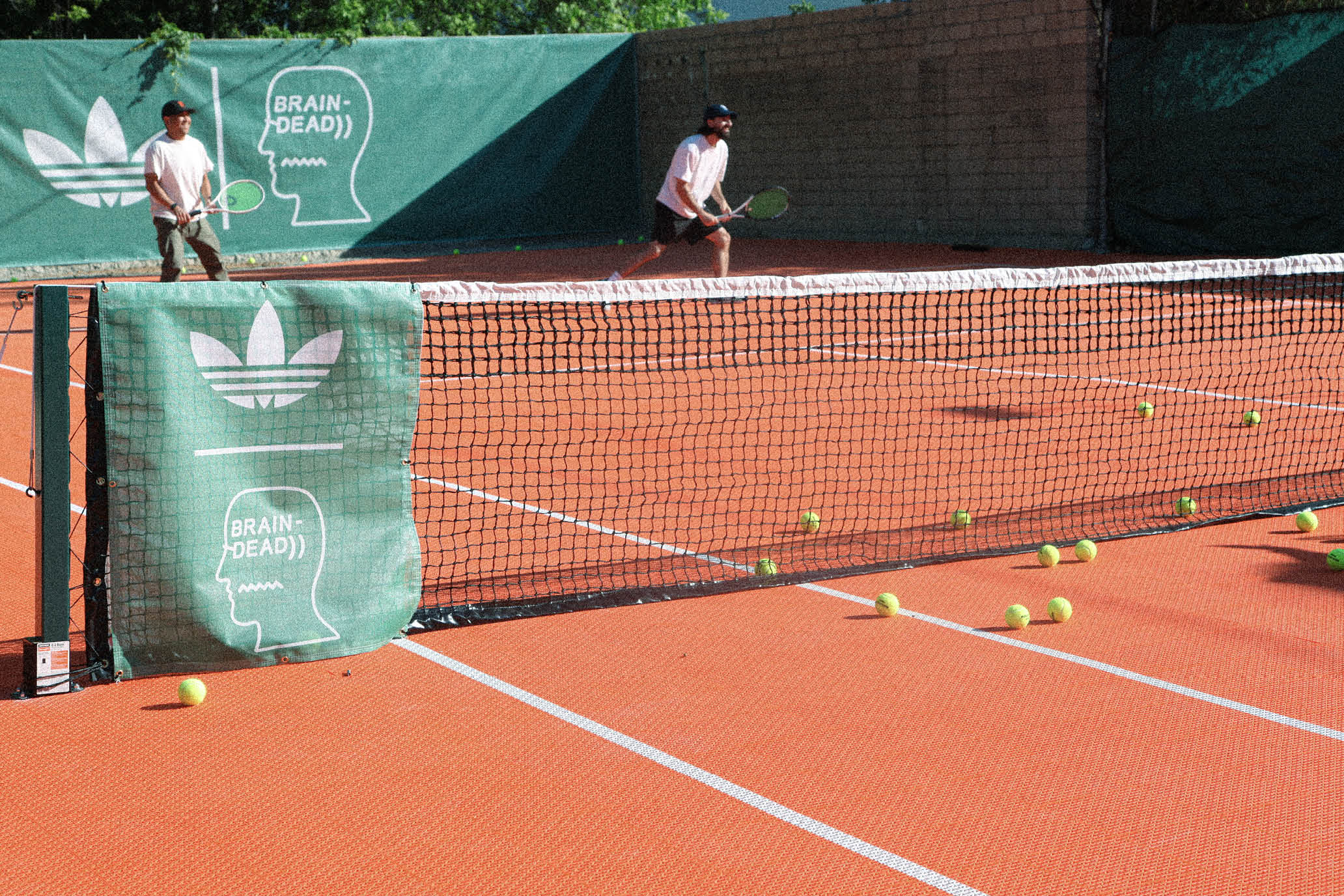

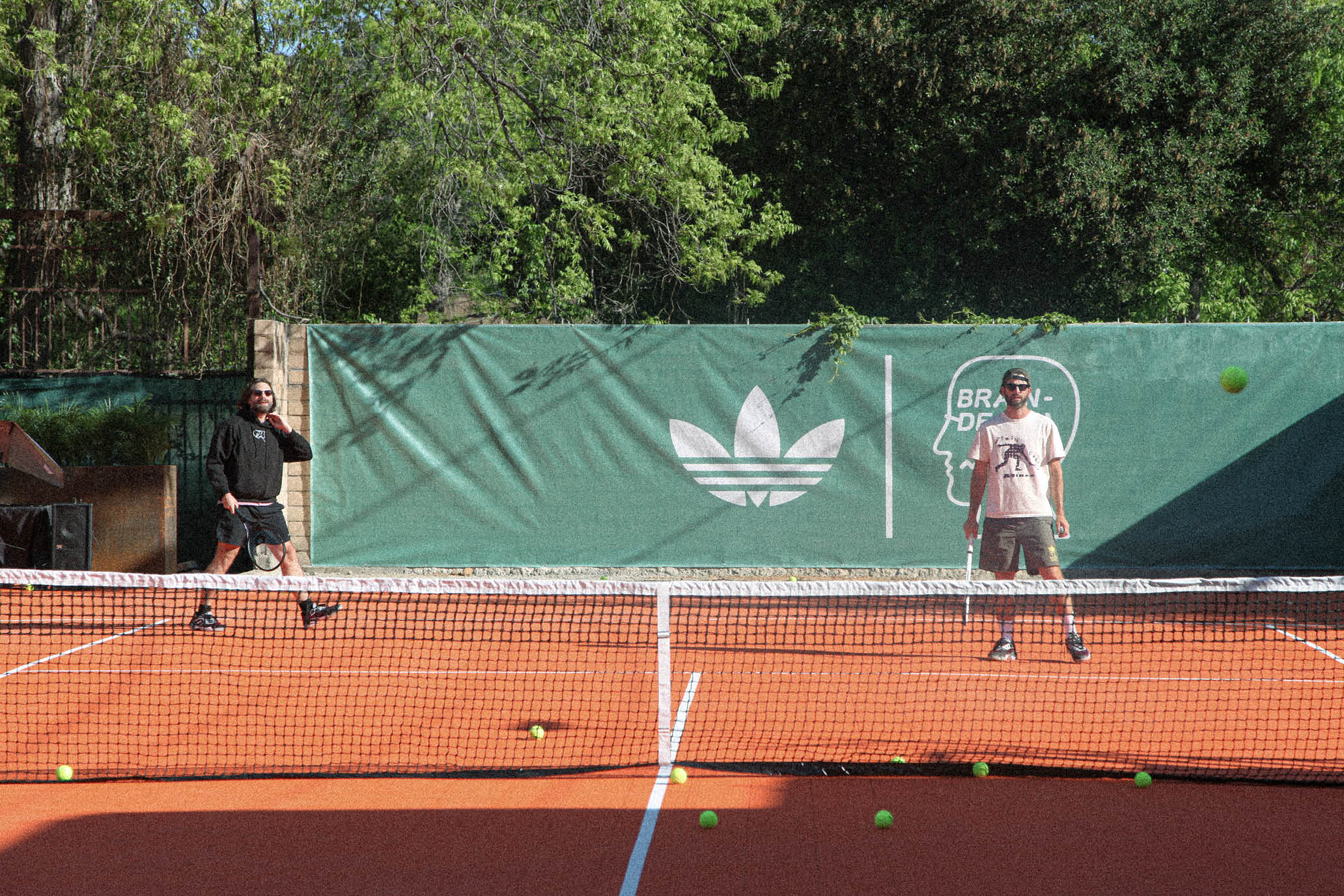

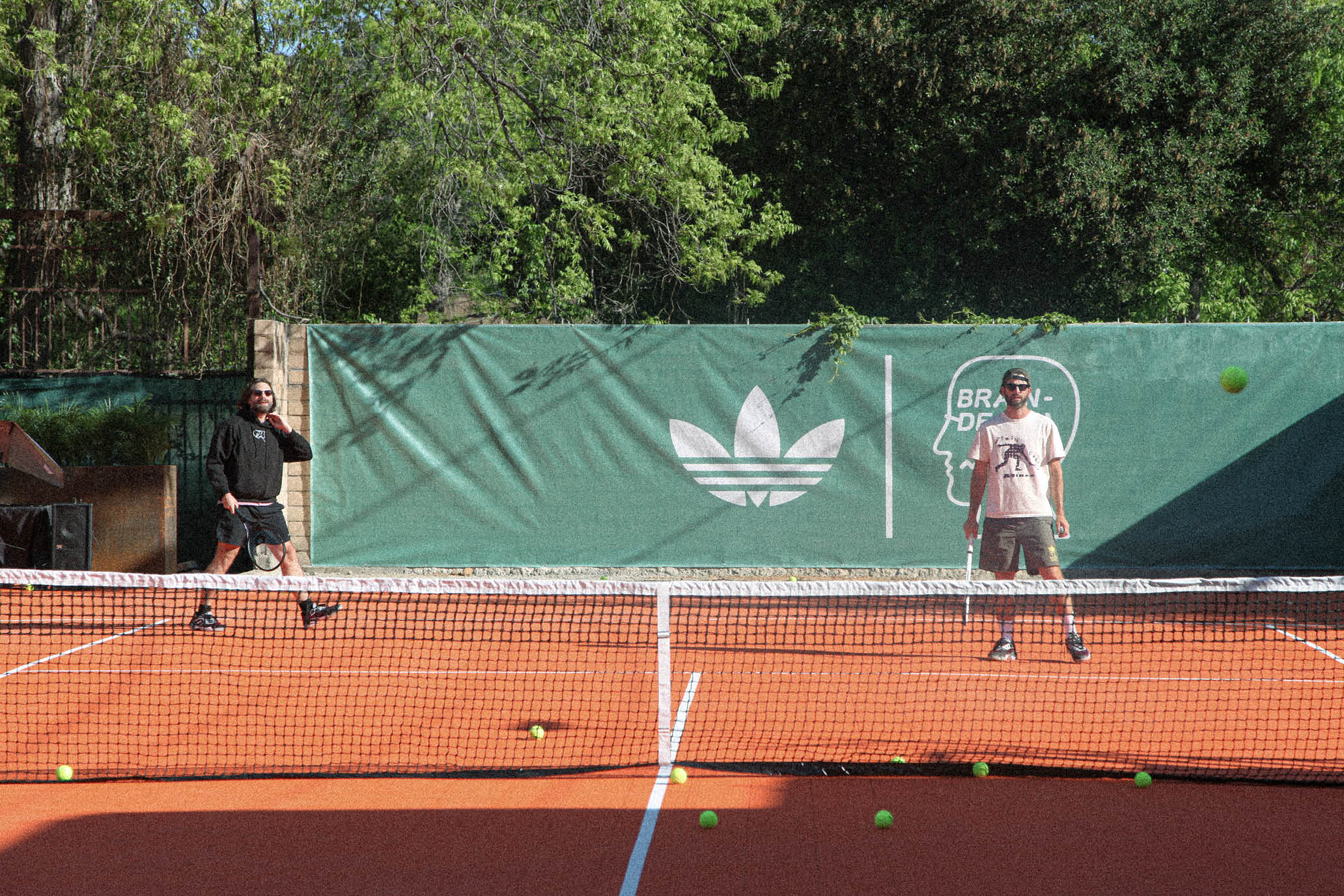

Photos: adidas Originals and Brain Dead Hold Court in LA

Photos: adidas Originals and Brain Dead Hold Court in LA

Friends and family gather for the launch of the brands' new SS25 collection and interactive tennis pop up in Highland Park.

Friends and family gather for the launch of the brands' new SS25 collection and interactive tennis pop up in Highland Park.

By TSS

April 24, 2024

SIGN UP — YOU'RE ONLY AS GOOD AS YOUR SECOND SERVE.

Nothing Special

Nothing Special

Nothing Special

Joao Lucas Reis da Silva talks coming out and moving up.

Joao Lucas Reis da Silva talks coming out and moving up.

By Sebastián Fest

April 25, 2025

Joao Lucas Reis da Silva the Rio Open in 2024. // Getty

Joao Lucas Reis da Silva the Rio Open in 2024. // Getty

This article was produced by CLAY and has been published collaboratively. It appears on their site as well.

RIO DE JANEIRO—Joao Lucas Reis da Silva, the Brazilian who at the end of 2024 became the first player on the ATP Tour to come out as gay, is clear about one thing: It is very unlikely that he is the only one.

“I don’t know about anyone else, but I think it’s unlikely that I’m the only gay player on the tour,” said Reis during an interview with CLAY in Rio de Janeiro.

Reis, a smiling young man who is looking for a place in the tennis elite—his current ranking is 325—was 2 years old when he sat on the bed between his father and mother, took out his pacifier, and stammered “Guga” while pointing to the television.

Twenty-two years later, he again turned heads when he simply uploaded a photo with his boyfriend on Instagram.

“Happy anniversary, happy life, I love you so much,” he wrote on the social network in December, accompanying a photo in which he was seen with his partner, actor Gui Sampaio Ricardo.

Reis da Silva, who reached No. 204 in the ATP rankings at the end of 2023, has been climbing back after an injury derailed him at the end of 2024.

Men’s professional tennis does not have a history like Reis da Silva’s. Players like the American Taylor Fritz told CLAY at the time that an openly gay player would be well received by his colleagues, while the Peruvian Juan Pablo Varillas posited a different theory: “Maybe there are gay tennis players, but they are afraid. This is a macho sport.” (This is in stark contrast to the WTA, where there have been many openly gay players.)

In an in-depth and relaxed conversation on a humid night in Rio de Janeiro, on the sidelines of the Rio Open played in February, Reis da Silva explained that it was not and is not his intention to become a role model.

“I see that many people look at me and tell me they are proud, and that’s very good. But it’s not something I’ve sought,” said the Brazilian, who, between sentences, looked up to find himself with an unrivaled postcard view of Rio: Christ the Redeemer embracing everyone from the top of Corcovado hill.

What are your goals on court this year?

This year I want to play in the Grand Slam tournaments. Last year I came close to doing it. I almost got into the main draw at Roland-Garros, but I got injured and didn’t play for a while. I feel that my level is there, although I still have to improve some important things.

You don’t earn much money in your current ranking position. How do you finance your career? How do you manage to keep traveling and playing?

I have help from people who believe in me. And I have the support of my city, Recife, and my state, Pernambuco. I can travel with peace of mind until October this year. I hope to play in the US Open qualifiers this year and go to the Australian Open in 2026.

At what age did you start playing tennis?

At the age of 4, very young. The whole family plays. My dad, my mum… My brother played too, he played in junior tournaments in Brazil, but he stopped at an early age, at 15 or 16. I wanted to do everything my older brother did, he’s six years older than me.

As a child, who were your tennis idols?

My first idol was Tsonga. If I saw him on the TV I would drop everything to watch him. I was 8 or 9 years old and they used to call me Tsonguinha [little Tsonga]. And Rafa [Nadal] and Guga [Kuerten] were my other two idols.

You weren’t born when Kuerten won the 1997 Roland-Garros…

My mum always tells a story. I was 2 years old and my parents were in bed watching a Guga match on television. I got into bed between them, took out my pacifier, and said, “Guga.”

You posted that photo in December congratulating your boyfriend on his birthday. And you said at one point that the reactions surprised you. Why?

They surprised me very pleasantly, because the reactions were much better than I expected. I already had the support of my family, my friends, my coaches…. But there was a part of me that was a little worried. When I saw that everyone was sending me messages saying “Good for you!” and things like that, I felt really good. It was a very motivating feeling.

You were worried once you’d posted the photo, but before posting it you did it happily and almost unconsciously, didn’t you?

Yes, when I did it, I did it almost unconsciously, just because it was his birthday. And when I saw that the photo had repercussions in Europe, all over the world, I got a bit worried. And then I sat down and started to think. I told myself no, what I had done was right, that I didn’t have to hide anything from anyone else, that I had already lived that way for too long, trying to make sure that nobody knew anything. When I saw that the reactions were very good, I calmed down.

What was the most pleasant reaction, or the one that surprised you the most?

Billie Jean King wrote to me, a lot of people that I can’t remember now, a lot of likes. And a lot of people around me too, people I already knew I could count on, but who wrote me a lot of nice and kind things. And a lot of people I don’t know, but who told me they admired me. That was the biggest motivation.

Did you receive any messages from the ATP or the International Tennis Federation (ITF) authorities?

No, no, not from them.

Do you think that with that photo you uploaded in December, you can help other gay players feel more secure, more relaxed, more confident about uploading a photo like that themselves?

If that happens it would be great. I don’t know if I’m the person who should be setting an example. My life hasn’t changed that much. I have to wake up in the morning and practice at nine. Not much has changed for me. I have to do the same thing. But I see that a lot of people look at me and tell me they are proud, and that’s very good, but it’s not something I’ve sought.

Don’t you want to be an icon or a role model?

No, because I have a lot of things to worry about with my tennis and with being a better player and a better person. But, well, if people feel represented in me, that’s a very good thing. But it’s not something I want, it’s not my goal.

You said in statements to the Brazilian press that in the years when you were telling your friends that you were gay, the homophobic jokes and sexist comments in the locker rooms or on nights out began to disappear.

Yes, and I think that can happen in society as a whole, not just with my friends. It was a sudden change, things I heard that I never heard again. They might talk among themselves when I’m not there, but when I am there, the atmosphere is one of total respect. It was one of the best things I’ve ever felt. A long time ago I was someone who didn’t want to talk to anyone about it, and when I started talking, when I felt calmer about myself and started talking to my friends, to everyone, and I saw that the reaction was one of protection, of support, I felt calmer. It did me a lot of good.

In what sense?

I started to live much more relaxed, much more relaxed. My relationship with my coaches improved a lot—with my family, too. I could talk about things that I didn’t talk about before. I was 19 when I spoke, it was during the pandemic.

How did your parents take it?

For them it was a shock at first, although my mother told me, “I already knew, I was waiting for you to speak.” She could have told me before! [Laughs]

Mothers know.

Mothers know! The truth is that this had been maturing for a while, and I’m very happy to have come this far.

There is a statistic that indicates that, historically, approximately 10 percent of the population is gay. That 10 percent is not reflected in the ATP Tour. Does that catch your attention?

I don’t think I’m that special, so I can’t be the only one, I can’t be that unique. I don’t know anything about anyone, but I think it’s unlikely that I’m the only gay player on the tour.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Italian Accents

Italian Accents

Italian Accents

Coco Gauff and New Balance to team up with Miu Miu this summer.

Coco Gauff and New Balance to team up with Miu Miu this summer.

By Tim Newcomb

April 23, 2025

Images courtesy of New Balance

Images courtesy of New Balance

Coco Gauff plans a fashion-forward spin through three tournaments this spring and summer. As part of a New Balance x Miu Miu partnership, announced today, Gauff will wear both apparel and footwear created in collaboration with the Italian line, while playing in Rome in May, Berlin in June, and Cincinnati in August.

Gauff will wear a custom co-branded version of her signature shoe, the Coco CG2, reimagined in collaboration with Miu Miu, while also wearing different co-branded apparel for each tournament. In Rome, Gauff will don navy and white with red accents. The Berlin kit features white and green with a sky-blue accent, and her Cincinnati outfit features white and royal blue with accents of red. The designs use color blocking for a “sharp, clean and modern look,” New Balance says.

Before and after matches, the New Balance x Miu Miu collaboration for Gauff will be expanded to include silk zip-front hoodies and track pants. Gauff will also wear new iterations of the 530 SL sneaker in leather and mesh off the court.

Started by Miuccia Prada in 1993, Miu Miu now has over 100 stores worldwide. Fans of the gear will have to wait to purchase it until a launch event on Sept. 10 where Gauff will appear at the Miu Miu store in New York City.

Images courtesy of New Balance

Images courtesy of New Balance

Follow Tim Newcomb’s tennis gear coverage on Instagram at Felt Alley Tennis.

SIGN UP — YOU'RE ONLY AS GOOD AS YOUR SECOND SERVE.

SIGN UP — YOU'RE ONLY AS GOOD AS YOUR SECOND SERVE.

He’s Got the World on a String

He’s Got the World

on a String

He’s Got the World on a String

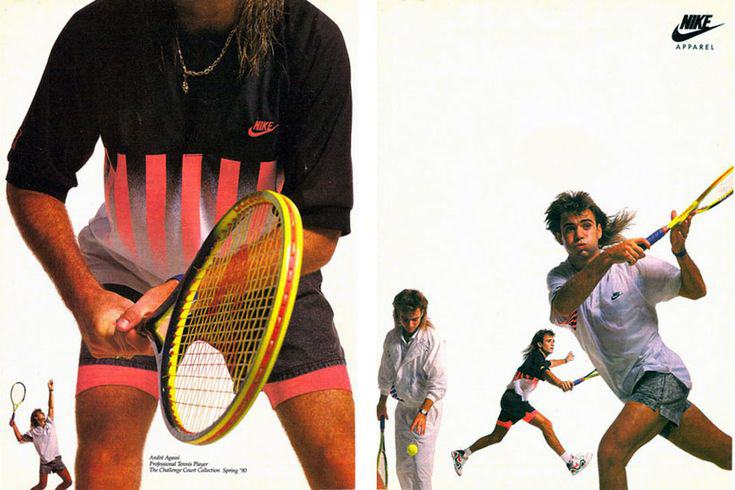

Review: Netflix’s “Carlos Alcaraz: My Way”

Review: Netflix’s “Carlos Alcaraz: My Way”

By Patrick J. Sauer

April 22, 2025

Carlos at Indian Wells 2023. // David Bartholow

Carlos at Indian Wells 2023. // David Bartholow

A month prior to Frank Sinatra’s death in May of 1998, the terrific essayist Sarah Vowell recorded a This American Life piece pleading with television anchorfolk—both high- and lowbrow—to refrain from doing the thing they were 100 percent going to do when announcing his death. Vowell lamented that each and every obit treatment would be “accompanied by the same damn song, the most obvious, unsubtle, disconcertingly dictatorial chestnut in the old man’s vast and dazzling backlog…‘My Way.’” She was dead-on, it played on every network news account, and she’s right about the song itself. The charms of Ol’ Blue Eyes’ ridiculous full-throated sentimental pomposity are not lost on me, but I recognize it’s the most “Fat Elvis” song—both figuratively and literally—in his entire catalog. The one thing the song does have going for it, though, is a sense of gravitas from one of the greatest to ever do it. “My Way” became his personal anthem (a thing he regretted as daughter Tina said he came to hate the “self-serving and self-indulgent” ditty) to such a degree that it’s become nostalgic lingua franca for elderly people on their way out who want to believe they lived a full uncompromised life. Even though they assuredly did not.

Whenever someone says they “did it my way,” Sinatra’s slow, shallow warbling instantly starts playing in my head. So it was rather unnerving to see it used in context with a 21-year-old tennis star whose life is really just starting to unspool, but it’s the title of Carlos Alcaraz: My Way, a Netflix docuseries debuting today. It may seem like a stretch to link the two, and it wouldn’t be at all surprising if the young Spaniard isn’t aware of Sintara himself, let alone his signature song, but it’s such an end-of-the-journey expression that it begged questions of youth before I even watched it. Namely, how can a kid claim to be doing things “my way” before most of his adult life is yet to come? And furthermore, has Carlitos led enough of a life to warrant a three-part treatment? I’d come to find the scenes that loom largest on this front are when the wise old owls Agassi, Borg, McEnroe, and Navratilova take stock of Alacaraz’s long-game potential, the lines on their faces and the silver in their hair (minus the former mullet man) showing that their years are moving in Sinatra’s direction.

The series is a straightforward, behind-the-scenes look at Alcaraz’s 2024 season. It features the highs of wins at the French and Wimbledon, and the lows of bowing out of the Olympic doubles quarterfinals in Rafael Nadal’s last go-round and a huge meltdown and an all-timer four-bang racquet-obliterating smash (rendered in brilliant slo-mo, the production quality on My Way is superb) in a loss to Gael Monfils at the Cincinnati Open. All in all, a good year for the world’s current No. 3, who is hoping his right leg issues in Barcelona didn’t ruin a potential 22nd Madrid Open finals birthday celebration in front of a raucous home crowd in a couple weeks. If so, his family will have to triple the size of the “tennis court ringed with white balls” cake he was presented on his 21st birthday, one of the charming moments of the series. Alcaraz’s million-watt smile, ebullient personality, and clear love of busting cojones with his boys—a big-time athlete in constant fits of laughter is a sight in itself—make the series an overall entertaining watch, but the first episode was lacking in actual drama and a sense of purpose. Since we know he won Indian Wells in 2024, the storyline of him overcoming multiple 2023 injuries doesn’t have enough juice to really justify My Way’s existence beyond a solid Carlitos hang. That and, presumably, keeping the relationship between streamer and subject happy for further Netflix Slam exhibitions and the forthcoming Rafael Nadal series.

Speaking of Nadal, My Way finds its footing and takes off in the second and third episodes when Rafa enters the picture by making fun of Alcaraz for liking too many Majorcan girls’ Instagram photos. In the interview sections of the series, Alcaraz only gets heated once, and it’s in talking about how he has no desire “to be the heir to the Spanish throne,” and how it’s both irrelevant and insulting to Nadal to mention them in the same way just because he and Rafa both won three majors by age 21. He also lets a deep well of teary on-court emotion out after losing in the Olympic singles finals to Novak Djokivic, but what really seems to be breaking Carlito’s heart is knowing he had one shot to medal with his idol and it didn’t happen. The Alcaraz-Nadal doubles experiment flamed out in the quarterfinals, and for the first time, the young gun witnessed an Olympic tennis dream come to an end, one that can never be captured again. It’s probably the first time Carlitos came face-to-face with the realization that the fun is fleeting and nothing, notably athletic careers, lasts forever.

Fun, however, is what Alcaraz is currently after, and the very piece of advice Roger Federer gives him, upon their first real chat, is to find it elsewhere at every tournament and in-between stretch. (For Nadal, we learn it means pre-match Parcheesi.) Carlos eats it up, exclaiming to an assembled practice crowd after Fed leaves that he has “gotten some of the magic” on his arms from their warm embrace. Fun is also why he ignores the advice of his team and his pill of an agent—a whinger who wants sympathy for being away from his family every year on his birthday at Wimbledon, which somehow his teenage kids can’t get to even though a Barcelona–London flight is two and a half hours—and goes to Ibiza for a nonstop week of partying after the 2023 French Open semis loss to Novak. It’s seen by Team Alcaraz as the immature act of someone who isn’t properly training for grass season. Then he won Wimbledon, so he did it again in 2024. Same results. Fiesta on, amigo.

The trips weren’t simply a dude blowing off steam, either; they were part of Alcaraz’s astute understanding of what he needs mentally in order to never “see tennis as an obligation.” What he is trying to figure out is how to do it his way, to lay down a road map that doesn’t break him on the journey to “sit at the table with the Big Three.” There is already an insane amount of pressure and expectation that 20 majors are a sure thing, but in true Gen-Z fashion, he doesn’t seem as obsessed with it as everyone in his orbit. Other than his mother, of course, who has the best line in the show when she says, “I don’t want my son to turn into a worn-out toy later on.”

Neither does Carlos Alcaraz, because he admits that right now, he doesn’t know if he wants to become a “slave to the game,” a dismal idea that his coach, the unsmiling Juan Carlos Ferrero, posits multiple times throughout the series. Alacaraz isn’t having all of it; he’s determined to not hate a sport he loves or live a life he doesn’t want. Given the crash-and-burning of so many young stars over the years, it’s admirable and feels very Gen-Z for a man his age to put such stock in self-care. Is part of it playing to the cameras? Probably, but Alcaraz is so likable in My Way, I swallowed it whole. I’m already on record here hoping he knocks Novak out of the top spot in 2040 give or take, but Carlitos won me over even more with his refreshing approach to his crazy, high-profile, jet-set existence. It’s best encapsulated in Alcaraz’s big-picture “how” he’ll know if his tennis career is on point: “I’ll choose happiness over massive success, because happiness is already success…”

Come to think of it, that reminds me of something a certain crooner facing that final curtain once asked and answered: “What is a man, what has he got? If not himself, then he has naught…”

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Performance First

Performance First

Performance First

How Joelle Michaeloff, vice president of design at Wilson, used “stealth technology” to make fashion forward tennis clothes.

How Joelle Michaeloff, vice president of design at Wilson, used “stealth technology” to make fashion forward tennis clothes.

By Tim Newcomb

April 18, 2025

Marta Kostyuk and Alycia Parks representing Wilson dresses. // Getty

Marta Kostyuk and Alycia Parks representing Wilson dresses. // Getty

At more than 110 years old, Wilson sure is showing serious spunk. One of the oldest American sportswear brands out there launched tennis fashion anew five years ago behind the creative direction of Joelle Michaeloff, a veteran of brands such as Lululemon, Urban Outfitters and Spiritual Gangster. The fashion-forward nature of the designs—both on the professional tours with the likes of Marta Kostyuk and Alycia Parks and for the playing masses—has pushed Wilson past the idea of an equipment-only company and into a tennis style leader.

That was all so very intentional.

The Second Serve’s Tim Newcomb connected with Michaeloff, Wilson’s head of design, who launched the brand’s efforts in what has become one of the hottest fashion-forward forays in tennis in the past few years. Here she shares the strategy behind Wilson Sportswear.

How did Wilson’s history as an equipment maker impact the launch of Sportswear?

The only reason we are here is the equipment. We needed the equipment. For 110 years we have been making the best equipment in sport, and without that we would have also had to prove our innovation and prove we were technical. There are all sorts of things a new brand would have to prove, but this was Wilson, of course it would work.

How did that equipment mantra impact the fashion side?

For the fashion and style aspect of it, at the very beginning [Wilson Sportswear president] Gordon [Devin] asked me if we were to partner with someone to get this going as fast as humanly possible, what would I do and who would be the partner? I made a short list of people in fashion who had adjacency in sport to help validate what we were building from a style perspective. That’s why in 2021 we launched with Kith. [Kith founder] Ronnie Fieg has been a long-term adviser in terms of culture and style and coming at it from a different point of view than myself. I have grown up in fashion, technology, and athleisure, but Ronnie brought in a lifestyle perspective from an affluent, cooler consumer. I think that really helped to push and validate Wilson.

How did Wilson technology play a role?

Because we set out to always build beautiful product with innovation—what we call stealth technology—we set out to make it look good first and foremost, and at that time it was really missing in the market. What Wilson was able to make [apparel] look and feel like wasn’t happening at the time, and it set a groundwork for Wilson to create this. It felt natural—I’m biased, right?—but if you were to think what is Wilson going to create, it is technical and beautiful.

What was your strategy for tennis?

No. 1, we wanted to be meaningful to someone. We could have gone extremely broad—our first collection in 2020 was broad, and we threw a lot of spaghetti at the wall to see what would stick—but because of our position in tennis with equipment, we wanted to home in on tennis, especially since the appetite was there from the consumer, and the athlete was telling us to be there. We set out to win with women. We were already winning with men, so really focusing on women was another sort of risk. Women didn’t already have a place that was natural with Wilson, we just weren’t there yet. We set out to be technical and innovative first, but we didn’t want to look that way, we didn’t want to look techy. We were performance first and foremost just like the equipment but wanted to honor our past and bring it into the modern day. All of those things were top of mind.

How did that work out?

What’s crazy is out of the gate we were winning with women. We set out to do it and we did it. We are 60 to 70 percent women from a sales perspective, and that has pushed us to develop larger collections. We wanted to surprise and delight women, wanted to continue to build confidence for men (it takes longer to get a male consumer). Eventually the goal is to get closer to 50-50, but because the strategy is to win with women, I see us always being 60-40.

Why do you think you’ve had that success?

Wilson is an incredible brand. When I talk to anyone at any age, any generation, everyone has a story. When I tell people I work for Wilson, their faces light up. It is a loved American sports brand. That is a gift. I can’t believe I get to do this. There are not that many brands this old that at some point in their journey didn’t stay true to who they were or had a pivot point where they followed markets or trends. Wilson has been steady and true to the athlete, been an ally of the athlete since day one. I do feel the athlete was willing to give us a try. I do think that has helped us tremendously. We were a small and scrappy team operating like a start-up. We didn’t allow the enormity of the brand to slow us down or stop us from learning. Everything we do is learn and react. We still are the ally of the athlete, and we listen. Style is temporary. The real power is in listening and learning and reacting.

Can you describe the Wilson Sportswear aesthetic?

I describe it as classic, dependable. We pull from our heritage, but we do it in a new and modern way. We really have the right to do that more than anyone else because of who we are. We are not trendy; we are on trend. When you are classic, you are creating the trends anyway. If you saw us walking down the street in four years, would you be embarrassed or stoked? If embarrassed, that is not for the brand.

How important was it to get an athlete like Marta Kostyuk on board?

When we signed Marta I was heavily involved. I had never pitched athletes before, it was a new muscle for me. I was passionate about finding the right athlete. Who we signed was so incredibly important and critical. We needed to sign an elite athlete who could give feedback as fast as possible. They had to want to wear the brand, want to give feedback, be in our process. That is not everybody. The moment I knew this was going to be big was when we did our first fitting [with Kostyuk], and as soon as she put it on, all the fears and things of “Is it too heavy, will she feel comfortable?”—it all melted away. She said, “This is amazing, look how cute I look,” all of these things. That was the moment for me when I knew we had something here, we are in a good place. If we can dress an elite athlete and she loves it and feels comfortable in it and is game to help us make it great, this is big.

How imperative was it to get other athletes on board?

It has been really important. I can gush about Marta, but we also wanted different types of players, different body types, different aesthetics. We really wanted to round out who we are designing for, so, not going after a specific niche but opening the aperture. Each player is unique; they dress different, play different, and have different personalities and preferences. When we met Alycia [Parks], she didn’t like pleats—I think we’ve changed that, by the way, so now she will wear whatever and is super happy with how her pleats move. Her first thing she said to me is “More, everything plus.” She wanted everything extra. Her style is over-the-top. Peyton [Stearns] is more sporty. They all have different preferences, so we don’t just focus on one person’s feedback.

What did you do with Marta that worked?

Every other brand is all about their logo and all about how big it can be, maximizing it front and center. One of the first things we did with Marta’s first season on court wearing Wilson—which was a pretty big risk, and I took a lot of heat for it, but it was very calculated and on purpose—was you could barely find the logo. I wanted what she was wearing to be more important and to stand out, so people started to talk. The amount of conversation about “Where is the logo on Marta?” I told people [internally] it will get bigger—it is not any bigger, by the way—it will get more obvious, but give me a little more time. It needed to be about her style and about her before it was about Wilson.

We broke every rule in setting Marta up, so we weren’t going to follow the rules now. It was important for her personal style to show that it really exuded who she was. It wasn’t about us; it is about her. She is a tremendous athlete, she’s beautiful, an amazing player and passionate. We wanted that to be first and foremost. Without seeing the logo, Marta started to be called the best-dressed athlete on court. You could only see the logo when you got really close, which was very much my plan. All of it was my plan. She is aligned with the vision of not putting logos all over her—the logos represent money, of course—but it was about building her brand. We are not putting clothes on athletes because it is an advertisement; we are investing in athletes. The wedding dress only occurred because of that relationship, because we understood how to dress Marta with her help.

What are you most proud of so far?

Working for Wilson has been a gift and almost feels like a dream to be able to put an aesthetic around such an amazing 110-year-old brand. It seems insane, and we have been running so fast you almost forget to stop and pause. The fact that we were able to get up and running so quickly and put on elite athletes right from the beginning, I am really proud of our innovation, our quality. We can do all the things we talked about, but if we didn’t build the best product, in my biased opinion, it wouldn’t be great to me. It must be all of those things. I want people to buy it and hold on to it for a really long time.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Signature Moves

Signature Moves

Signature Moves

Digging into the design of Coco Gauff’s New Balance shoe with the brand's head of tennis footwear, Josh Wilder.

Digging into the design of Coco Gauff’s New Balance shoe with the brand's head of tennis footwear, Josh Wilder.

By Tim Newcomb

April 11, 2025

PHOTOS BY TSS

PHOTOS BY TSS

Coco Gauff signed with New Balance at the age of 14. She was so young when she landed her first signature shoe in 2022, designers added a charm detail to fit her interests. Now, at 21, Gauff is on her second signature shoe with the Boston-based brand, an effort that has shown her maturing view on style and performance.

As the only signature model for an active player in the sport, the Coco CG2 offers rarefied air in the sport of tennis. The debut model, the Coco CG1, launched in summer 2022 and featured colorways aplenty over two years, akin to a signature basketball sneaker. The Coco CG2 came in time for U.S. Open 2024, even now rolling out a fresh array of designs and colors while spawning a low-top Coco Delray model.

The Second Serve’s Tim Newcomb connected with Josh Wilder, New Balance’s footwear product manager for tennis, who has worked hand in hand with Gauff from the start.

How has your relationship with Coco evolved?

Our relationship with New Balance and Coco Gauff started when she was 14 years old. Now that she is 21, she has changed a lot as both a player and a person. I think at the beginning of the relationship with the Gauffs, a lot of the decisions were left to us. They would say, “You are the experts,” and “Lead the way.” A lot of the design cues were stuff New Balance already knew. As she matured, her design matured. The CG1 had charms on the top eyelet, and at the time she was a big fan of accessories. Over the years that has started to evolve, and the way she views product and color has been really awesome. We get a lot more critical feedback that we have all loved and welcomed.

What does the CG2 say that the CG1 didn’t say?

The CG2 was heavily influenced by the [New Balance] 550. A lot of tennis players, sneakerheads, and general consumers know, love, and have embraced the 550. While the CG1 was vintage with a modern twist and had a theme of ’90s basketball aesthetic, we were able to pull right from the archives from the 550 and give it a tennis twist with top performance attributes and the mid-cut silhouette Coco always wants. It was a nice collaboration of what Coco has always wanted in terms of a design aesthetic and what has been working with New Balance as a brand off the court. It married those two things up and was a great evolution.

What’s unique for New Balance tennis in the CG2?

She’s the only athlete for New Balance tennis that has the carbon fiber Energy Arc plate. We don’t offer it to the rest of the athletes, and that is something she has played in, tested in, validated in. It is awesome to see one of our top-tier technologies across running, basketball, and tennis be adopted by Coco. We are looking to further innovate in the future, looking to really advance it and change it up over the next year or two.

What’s an element of the CG2 you’re especially proud of?

It colors up extremely well, and it allows for a lot of versatility in the options we can offer. It looks extremely valuable in an all-white colorway, but for some of the most recent color-ups for Indian Wells and Miami we added a painted line on the midsole, and it took the shoe to a whole new level. It made it look faster, stand out more on court. The way we can color on the midsole geometry that is separate from the 550, that is the chef’s kiss of the product.

What are the Coco-specific callouts on the CG2?

The first version of the CG1 had a lot of Easter eggs because it was her first iteration of the shoe. The second one we pared it back a little bit and made it more tasteful. The coolest one is that the woven label on the tongue is from a 550 and we made it a tennis ball and added her signature. She does like those old-school basketball-type cues. We swapped out the tongue and made it specific to her, even though it is a nod to those woven labels from back then. On the underside of the woven label, when you are putting the shoe on, one shoe says “power” and the other one is “grace.” Those two words capture Coco perfectly. According to numerology, that is what the number two stands for: power and grace. Numerology isn’t for everybody, but as soon as we saw “power and grace,” we thought, “That is Coco to a T in the way she plays and handles herself on and off the court.” From the outsole standpoint, we hid “CG” right underneath the toe of the outsole. It blends itself into the design, but it is there if you look closely.

How does the CG2 pair up with on-court kits?

At New Balance, the tennis category is the most well-connected group in terms of footwear and apparel. The focus for many sports is on the footwear because the kit is a uniform. Tennis is, of course, a sport where you can lock up an athlete from head to toe. Within our walls we meet every other week specifically to talk about accessories to apparel and footwear color and staying very close to our color team, who understand the tennis schedule and know when things come out. Tennis is an international sport, and we are first and foremost tailoring our color for the tournament it is being played at, reminding people in Boston that tennis follows warm weather and we need bright colors. We try to use the tournaments as different personalities and use color to view those personalities. The French Open can be more elevated, fashion-forward, with maybe a couple neutrals, and the Australian Open more fun. It’s pretty cool educating everybody internally and externally on what the tournament is like and laddering that up to what we know our athletes like.

What’s one word to describe the CG2 technically

Energetic. To expand on that—and I know the question was only one word, but the combination of the FuelCell foam and Energy Arc carbon fiber gives a good propulsive feel, which in turn provides you energy for longer matches. It is energetic and lively, which is a challenge of a mid-cut shoe.

What’s one word to describe the CG2 aesthetically?

I was thinking versatile, only because the way we have designed it has led to a lot of people being able to wear it both on court and off court. The introduction of the Delray is a prime example of that.

What’s it like designing the only signature shoe in the sport for an active player?

It is equal parts exciting and then nerve-racking as well. Anytime you work on a signature shoe, you’re ultimately representing the athlete in a very pure form. It has their name on it. It has their signature on it. They are going to be the ones helping you market it and push it. The coolest part about it is ensuring their vision comes to life and making sure you hit all the checkpoints required to make that happen. With a signature shoe, brand goals are anchored around working with that athlete, ensuring that the vision they had at the start is coming to life.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Postcard from Monte Carlo

Postcard from

Monte Carlo

Postcard from Monte Carlo

Paris-based photographer Guillaume Tranchard sends a dispatch from the Rolex Monte-Carlo Masters.

Paris-based photographer Guillaume Tranchard sends a dispatch from the Rolex Monte-Carlo Masters.

Photography by Guillaume Tranchard

April 10, 2025

SIGN UP — YOU'RE ONLY AS GOOD AS YOUR SECOND SERVE.

The Standard-Bearer

The Standard-Bearer

The Standard-Bearer

One-on-one with Maria Sakkari.

One-on-one with Maria Sakkari.

By Ben Rothenberg

April 4, 2025

Maria Sakkari during the 2024 Paris Olympics, where she was initially intended to be a flag bearer. // Getty

Maria Sakkari during the 2024 Paris Olympics, where she was initially intended to be a flag bearer. // Getty

Maria Sakkari of Greece had been a post-pandemic fixture of the WTA top 10, with fewer highs and lows than her peers in a transitional era for women’s tennis. Sakkari stayed in that top echelon from late 2021 until the 2024 U.S. Open, peaking at No. 3—and nearly reaching No. 1 when Ash Barty suddenly retired in spring 2022. Though she was one of the world’s best and Greece’s best ever, she also drew constant critiques for not winning more titles or ever reaching a major final.

Sakkari’s run in the top 10 ended when she succumbed to a season-ending shoulder injury. Though she resumed playing this year, her ranking has been falling quickly. She arrived at this week’s Charleston Open ranked 64th; after a second round loss to eighth-ranked Zheng Qinwen, she will fall out of the Top 80.

Sakkari, 29, now lives in Washington, D.C., where her boyfriend, Konstantinos Mitsotakis, is in grad school. He is the son of Greece’s prime minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, which has garnered a new sort of attention on Sakkari since their relationship began in 2020. That relationship, she says, cost her the dream of a lifetime last summer, when she was selected to be the female Greek flag bearer for the opening ceremony of the 2024 Paris Olympics, only to have the honor revoked soon after, a shock that sent her spiraling and led to the shoulder injury that kept her out of the end of last season.

After chatting about their respective neighborhoods, Sakkari sat down to discuss all this and more with fellow Washingtonian Ben Rothenberg for The Second Serve:

We can talk a little bit more about D.C. later, but how are you doing? I haven’t seen you in a while. Physically, mentally, tennis-wise, how are you feeling?

I mean, obviously, I’ve been in a better place. But I’m happy that I’m healthy; that’s the most important thing. It took a few years for me to get injured. I got my first injury at 29. So that’s partially a good thing, but on the other hand, it was tough to just accept things after coming back from an injury.

My ranking obviously has dropped; I need to get it back to where it was. Not just because I want to be a top 10 tennis player again, but also I’ve been getting bad draws because I’m not seeded. I’m not high enough to avoid those players in early rounds. But at the same time, if you want to go deep into a tournament, you’ll have to beat those players no matter what round it is.

So it’s been tough. But at the same time, it was also very nice to take some time off. You know how hectic it is. Just to live a normal life and not travel every week—it was amazing. Obviously, my tennis going into the season wasn’t great. I had high hopes, but I realized pretty soon that it’s going to take time.

So I’ve been feeling very well the last few weeks, if I have to be honest with you. So I think it’s going to come. It’s just going to take a little bit more time. But I’m positive. I’m healthy. I’m feeling good. Happy. So that’s the most important thing.

You started by saying you were in a good place before. How tough is it to separate your mood and your self-confidence from your ranking? Especially because you spent so long in the top 10, very consistently, so now to see this bigger number next to your name—do you have to say, “That’s not real, I can’t worry about that too much”? It’s a challenge, I’d guess, to balance wanting to be realistic with also not wanting to be too negative or pessimistic and down on yourself.

Well, I think you go through both phases, I have to be honest. You go through that phase when you see the draws and you see that big number next to your name. But then again, you think of how so many good players have been there, so many players who have had a lot more injuries and had to do that again and again.

Like I spoke to Paula [Badosa] a couple of times earlier this year, and she was like, “Maria, what did you think, that you’re just going to come back and play like you played before?” So talking to players that have had similar situations—or worse—has given me a lot of hope.

Because I feel like, okay, I’m doing the right things. It’s not like I’m not practicing or I’m not eating well or I’m not recovering. I’m doing all the right things. I believe it’s going to come. And if it says 50, 60, 80 next to my name, it’s fine. I just have to accept it.

You’ve had such a great career. I’m wondering what you’re most proud of that you’ve done…

Hmmm. Well, obviously getting to world No. 3 was huge. And playing that final in Indian Wells, I think…the winner was, because Ash Barty…

The winner would be No. 2, and then No. 1 Barty was about to retire.

Exactly.

I was thinking about that moment today because I knew I was going to talk to you. If you’d won, I don’t know if it was automatic, because Barty was still in the rankings in Miami, so it would’ve still required a result in Miami. And then Swiatek wound up winning Miami. But who knows if something different would have happened if it had been different in Indian Wells? We don’t know.

Yes. So putting myself in that situation just made me realize how good I’ve done in my career, and the consistency. Of course, even though I’ve had some ups and downs in my last three seasons, just managing to finish up there, I think, was huge. Because you see how good tennis is nowadays: Those first rounds are so tough.

So now I see how tough it is to get back to the top 10. Now I realize how good I’d been playing all those years just to stay there.

I think a lot of times people—certainly fans or media—sometimes do focus on what players haven’t done.

Of course.

Do you have that same sort of thing in your mind sometimes? Where you think, “Oh my gosh, I haven’t…”

…won a Slam.

Won a Slam. Instead of being like, “Wow, I was in the top 10 for three years,” something like that.

I think my time off really helped me realize that. Obviously, when you’re on a roll and you just go week after week, you tend to forget. You just want more, and you just don’t have the time to just get out of that situation, that movie you’re in, and just see the real picture.

So I was just being home, being with my friends, being with my boyfriend, with my family for a good amount of time—just being outside. You know, I wasn’t jealous of the other girls playing because I was happy where I was. I was happy that I was able to have that time off that I was looking for the last few years.

You had made all sorts of history for Greek tennis, you and Stefanos [Tsitsipas] coming up, parallel, together. Is that something you’re still proud of, what you two were able to achieve? Because before, you…

Yeah. [Rubs arm] I mean, you say it, and it gives me goose bumps.

Because it really wasn’t, before you two—your mom [Angeliki Kanellopoulou, former WTA No. 43] obviously was a good player too, but it wasn’t that level that both of you had at the same time.

Exactly. I think it was huge. Going into that first [2023] United Cup, being the highest seed because we were both No. 3 in the world. I mean, I really hope people back in Greece realize [the significance of] that, because it’s huge.

When you’re competing against countries like the U.S. or France or Germany, they’re big, they have big tennis history. And I’m just very proud of both of us, because tennis is now probably the third most popular sport in Greece, behind basketball and soccer. It’s big. I see that everyone plays tennis, everyone watches tennis, and I’m very proud of the work that we’ve done.

I was reading an article about you from Indian Wells about the Olympics and the opening ceremony and what happened there.

Oh yeah.

You were saying that that was something that you felt led to the stress that caused your injury. How much is that something that you’re still thinking about or disappointed about? Seems like it was a clear negative inflection moment in your career—not to bring up all the negative stuff.

No, no, no, of course. No, it’s fine, and I’m actually glad that you’re asking me, because it’s also very important for me to talk about it. In Indian Wells was the first time I really opened up about it.

People around the world have different kinds of problems, and that probably to someone is, like, nothing. But to me, I’m a very proud Greek. So when I was growing up, being the flag bearer for my country was my No. 1 dream. So when I got the call that I was going to be next to Giannis [Antetokounmpo], I was like, “Wow, this is the biggest thing that has ever happened in my career.”

And then everything got ruined because of my relationship, for political reasons. That really hurt me because I think every athlete deserves to be a flag bearer. Like going into the Olympics, everyone deserves it the same. I just felt like it wasn’t because I’m not a good tennis player, it was because some people didn’t want to support me because of who I’m dating. And to be honest, I have the best boyfriend in the world. I’m so happy he’s part of my life, and I wouldn’t change him, no matter what—I don’t care. He has been a very important person in my life and in my career.

So it was tough. I think my injury really—okay, it was overuse, physically. And also mentally, I was just broken. I just couldn’t take it. I was miserable in Paris. I just hated every minute of it. And you’re supposed to be in the biggest celebration of the sports and you’re just there, miserable. I just couldn’t. Yeah, it was tough.

Did you ever talk to or get any explanation from the Greek Olympic Committee?

Not really. And if I’m honest, I don’t want to. The previous president that called me and actually told me that I was selected, we’re still in touch. He really supports me. And I knew a lot of people that were really supportive in this. Obviously, I know why I was withdrawn last minute: There was a vote against me—which has never, ever happened in the history before.

And it’s not like you had some scandal or something that you did.

No, no. And I feel like politics has to stay out of sports. There’s [athletes] voting for this party or the other one—it doesn’t [matter] because they’re representing the country, no matter what their beliefs are.

So it was tough. And I’ll be honest, it was very tough for everyone around me and my family. I think it still hurts me a lot, but we’ll see. I will see about Los Angeles, but I will have to play really, really well in order to get a chance again to get the flag. It’s not going to be easy, for sure.

What has it been like being in this new world through your boyfriend, this political world? That’s a whole different space and part of the culture than I’d guess you’ve been in before. What have you made of this new world that you see through your connection to him?

We’re not so involved. He also tries to leave me outside of this world, which I really appreciate. But obviously I know—and I want to be aware of—what happens in the world. Not only in Greece, but being a tennis player, I don’t want to be limited on my knowledge.

And I’m supported by his family and everyone; they’re amazing people. They love me so much, and I love them, too. I see them as his parents. I don’t see his dad as the prime minister; I see him as his dad. And I see how nice they’ve been to me and how kind. And that’s all I keep for myself; nothing else, nothing more. But it’s fascinating, because he’s at the [Georgetown University] Foreign Service School, so it’s also nice to have someone that is not in tennis in your life, trust me. So I’m very happy with where I am in my personal life, and I’m just very proud of the work he’s putting in.

Did I see you two went to an Inaugural Ball? What was that like?

Yeah, we went because we had to represent his family. I had to go as his plus-one, obviously. No matter what you vote for or what you believe, it was for me—as a Greek person that has no place there, in a way—it was a nice experience no matter who the president is. Because I don’t feel like I will be given that chance again. I was there. I feel like it’s a [once-in-a-]lifetime experience.

As I said, no matter who you vote for, I just feel it happens once in your life. And life is all about experiences, and it doesn’t really matter where you stand.

When people are talking about you in this new political context, how do you keep your peace and your sanity and block out the noise? It can be very noisy around you sometimes for someone who doesn’t seem like they’re really asking for a lot of attention or controversy directly.

The thing is that because I’ve been with my boyfriend for a while, I feel like in Greece—because it’s mainly in Greece, let’s be honest; fans abroad don’t care who I’m dating—in the beginning there was noise behind it, but nowadays I feel we’ve been together for so long, so people don’t comment about it.

But it’s fine. I’m okay with some people not liking me because they support another party; not that it should be that way, but I don’t really care, to be honest. As I told you, I’m just happy with the person I am. And he makes me happy, and I make him happy.

And then on the tennis side, too, when people are saying, “She should win more, she’s overrated,” or whatever people say. How do you block that out?

You know, people are always going to say something. Like, even if I get back to top 5, they’re going to say, “Okay, yes, but she doesn’t have a Grand Slam.” Or “She’s never made it past the semifinal of a Grand Slam.” And even if you do win a Grand Slam, they’re going to say, “Yeah, but she [hasn’t won] a Grand Slam on grass court” or something.

You know this because you follow media all the time. If someone wants to say something, they’re always going to. Like, there’s negative comments about Djokovic. Like, what else does this guy have to prove? It’s just the world we live in right now.

So we have to accept it, and just keep going.

Sakkari at Indian Wells in March. // David Bartholow

Sakkari at Indian Wells in March. // David Bartholow

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

The Wonder

The Wonder

The Wonder

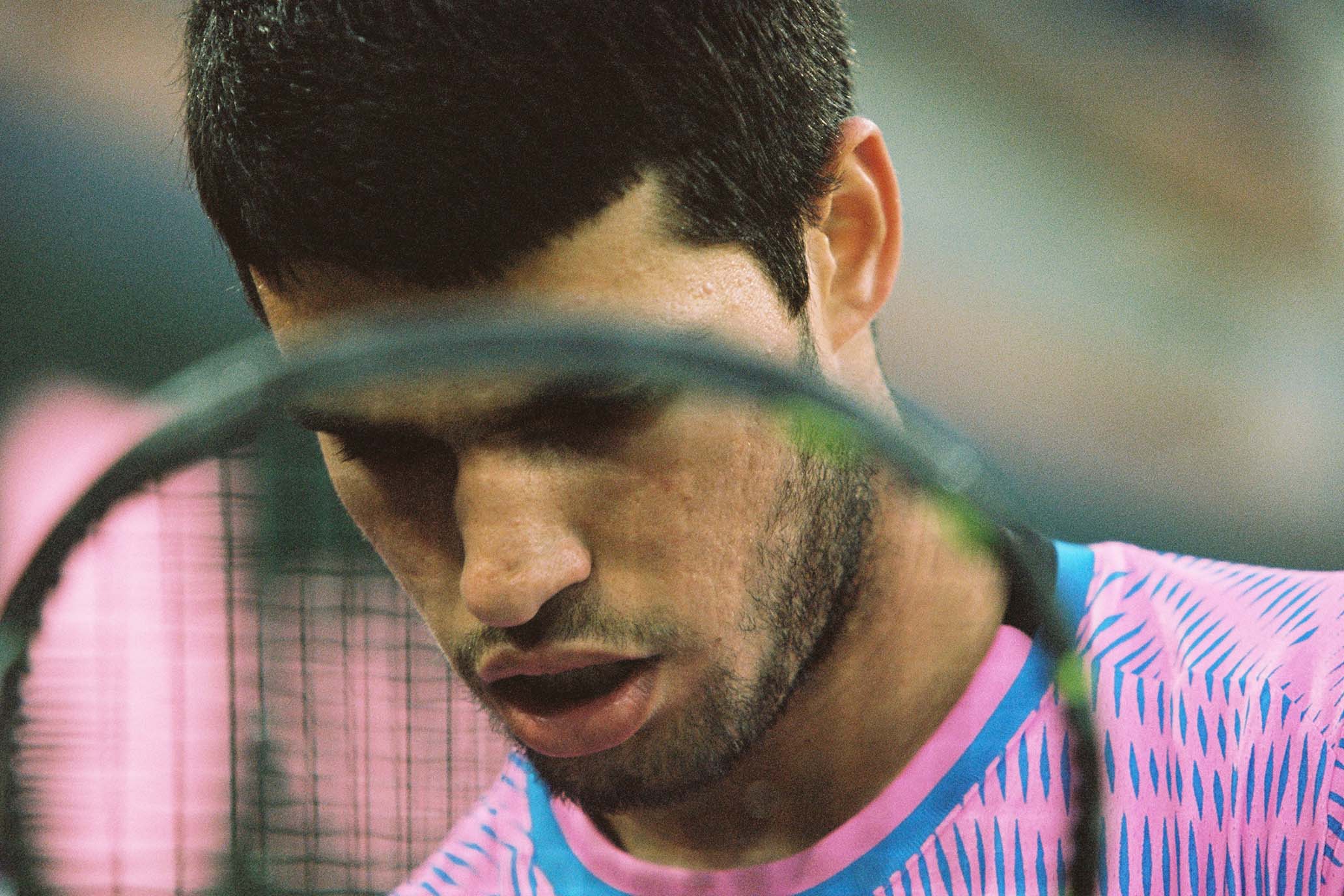

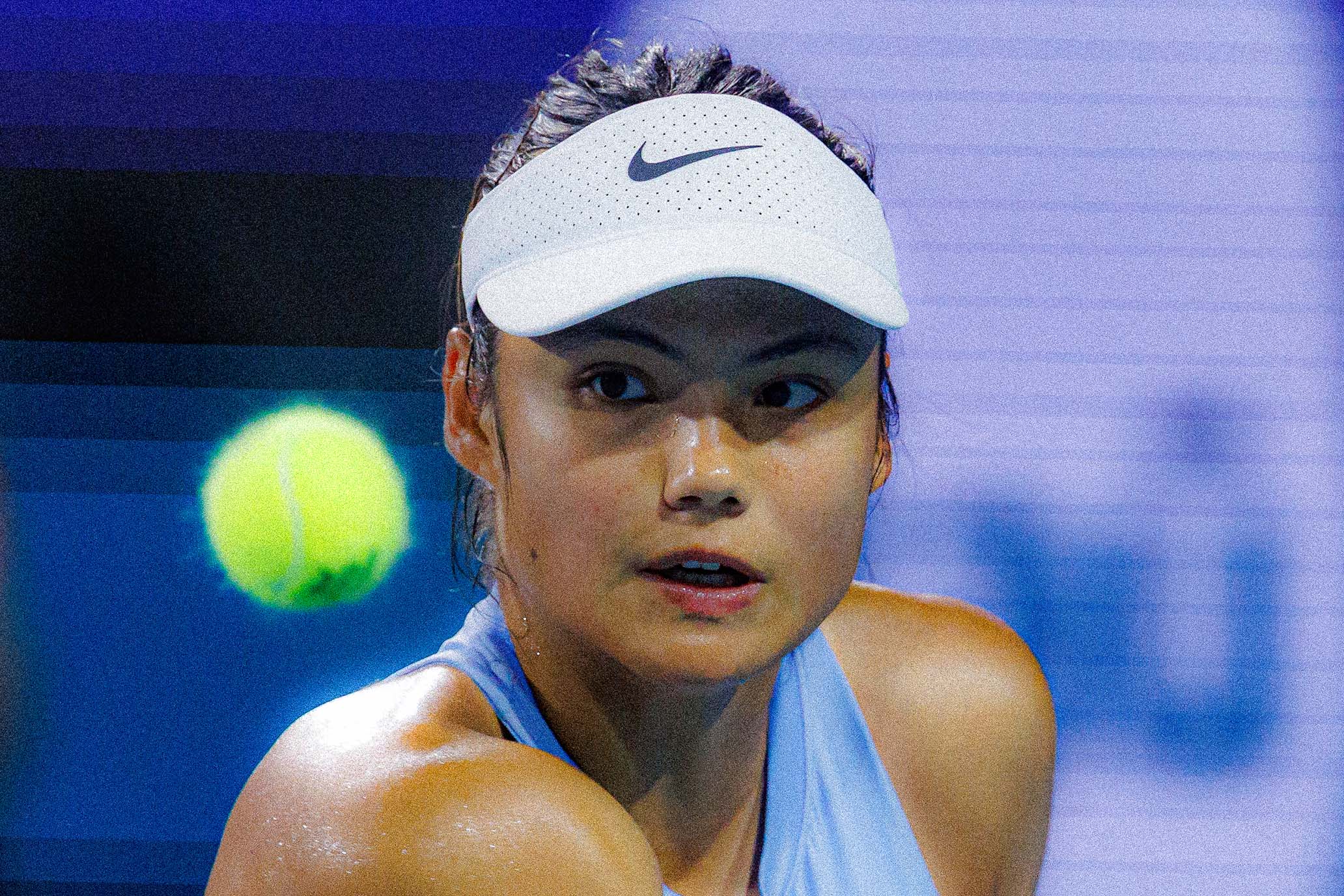

Emma Raducanu is putting it together.

Emma Raducanu is putting it together.

By Ben Rothenberg

March 28, 2025

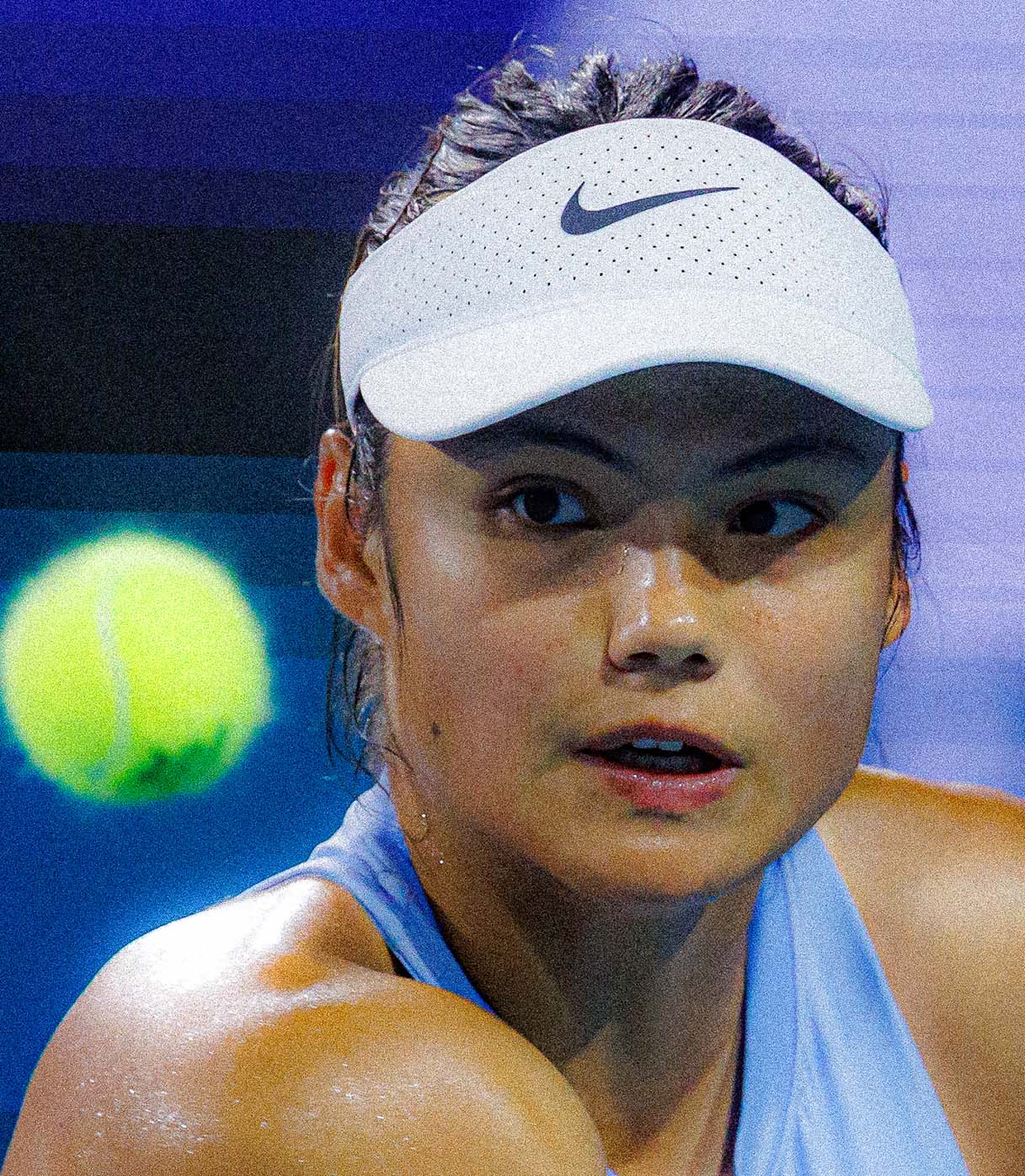

Eyes on the prize. // Getty

Eyes on the prize. // Getty

Three women notched their first career hard-court win over a top 10 opponent at this month’s Miami Open.

Ashlyn Krueger, a steadily rising 20-year-old Texan who recently reached the top 40, beat No. 8 Elena Rybakina; Alexandra Eala, a 19-year-old Filipina wild card ranked 140th who has been the breakout star of the event, knocked off both Australian Open champion No. 5 Madison Keys and No. 2 Iga Swiatek en route to the semifinals.

The third name is the most surprising inclusion on the list: Emma Raducanu, who eked out a win in a third-set tiebreak over No. 10 Emma Navarro—and whom most would have probably assumed would have checked that box years ago.

Little in Raducanu’s career has made logical sense, though. The milestone win over Navarro came nearly four years after Raducanu won a star-making title on the hard courts of the U.S. Open in the most improbable fashion—coming through the qualifying draw and then the main draw without dropping a single set.

It was a triumphant moment—with a sense of exultation multiplied by that 2021 U.S. Open being the first tournament played without significant pandemic precautions—and the 150th-ranked 18-year-old shot to superstar status in Britain and beyond.

Raducanu’s run proved that there aren’t strict prerequisites to being a tennis superstar. It wasn’t until a few weeks after her breakthrough in New York that she played a three-set match at tour level for the first time in a small tournament in Romania. Who wins a Grand Slam title before playing a third set?

These sorts of out-of-order moments have continued for her. When Raducanu beat Sloane Stephens in the first round of the next major, the 2022 Australian Open, it was her first time beating—or even facing—a fellow major champion.

In her post-match press conference that night, Stephens accurately pointed out how Raducanu’s reality had been so much more intense than her own because of the British multiplier on hype: “We [both] won the U.S. Open, but our situations are very different; I think she is carrying a whole country.”

The scale of attention was indeed nothing like Stephens—nor any other recent champion—had received. Perhaps most surreally, Raducanu’s name was postmarked onto all mail sent in the United Kingdom for a period after her win.

Stephens said that Raducanu’s trajectory had been “very backwards” and that she would have “a lot to learn.”

“I mean, she hasn’t been through much of anything yet, so there will definitely be some ups and downs and some crazy experiences that happen throughout her years,” Stephens said. “I think this is only the beginning…. I was talking to someone in the locker room and I’m like, ‘We’ll be here when she comes down.’ Not [just] Emma, but in general, it’s all a cycle. I think learning how to deal with it early on is the best way to handle it.”

But Raducanu didn’t seem to learn how to deal with it early on, and so her breakthrough moment didn’t create momentum. Some of the setbacks were clear unforced errors by herself and her management: Most clearly, after they had won the U.S. Open together, Raducanu chose not to retain her coach Andrew Richardson, the first churn in what would become a constant carousel of coaching changes.

But other hardships weren’t self-inflicted. Within months of the U.S. Open, Raducanu had attracted her first stalker—tragically a perennial peril in women’s tennis—a 35-year-old man who had come to her house multiple times in late 2021, once stealing a sneaker off her porch as a souvenir and another time decorating a tree outside the family’s home.

That aberrant behavior was an extreme example of a general obsession over Raducanu that had taken hold in Britain—particularly in their tennis media, which breathlessly documented her every move, even if no one was ever actually asking for that. One of the least popular articles I ever wrote was a freelance piece I picked up for The Telegraph at the 2022 Italian Open; their normal correspondent wasn’t going to be there for Raducanu’s pretournament media conference, their frantic editor explained to me over the phone, but they couldn’t possibly afford to miss covering the occasion. Naomi Osaka, whom I was shadowing that season for the biography of her I was writing, had withdrawn from the tournament, so I accepted the assignment. Raducanu said nothing interesting whatsoever in her press conference—which was down to the unremarkableness of the occasion more than herself. But because it was about Raducanu, The Telegraph promoted the article prominently. Readers in the comment section did not hide their exasperation at the oversaturation of Raducanu coverage at the detriment of broader tennis coverage in the paper, with several complaining that they’d much rather be reading about the recent star turn of Carlos Alcaraz.

The British press was covering every granule of what was ultimately an unspectacular sophomore season for Raducanu. There were a couple highlights—she managed to bagel Serena Williams and Victoria Azarenka in back-to-back matches in Cincinnati—but Raducanu didn’t make it past the second round at any of that year’s majors. Her loss in the first round of her U.S. Open title defense knocked her well back outside of the top 50.

Raducanu spent the next few years unable to stay injury-free and unable to keep a steady coach. Raducanu, whose sponsor portfolio has remained lucrative despite her mediocre results, often inspires eye rolls in tennis circles, particularly for traits such as her refusal to ever deign to play a qualifying draw no matter how her ranking had plummeted, only competing in events that will give her a wild card into the main draw. But she also sometimes inspires sympathy, such as when a new stalker began following her at tournaments ranging from Singapore to the Middle East earlier this year, triggering Raducanu due to her past brushes with fixated fans.

After hiring the strength coach Yutaka Nakamura for this season—who had previously worked with Maria Sharapova and Naomi Osaka—the 22-year-old Raducanu is finally starting to look sturdier. During her quarterfinal loss to fourth-ranked Jessica Pegula in Miami, Lindsay Davenport earnestly praised Raducanu’s improved fitness on Tennis Channel, saying that it was “a fantastic sign that her body can hold up” through five matches. It was the first time Raducanu had played that many singles matches at one tournament since the 2021 U.S. Open, after all, and it was enough to put her back into the top 50 for the first time since the ranking points from that win had expired.

Jim Courier, Davenport’s co-commentator, agreed and said that Raducanu was proving she wasn’t as weak as believed. “There probably is a little bit of a thought that she might not be the toughest out there on the court,” Courier said. “She’s showing some toughness out here tonight. That, I think, is important as well.”

“To get the locker room, the street cred?” Davenport asked.

“Also for herself, in order to build up her own belief that she can overcome these physical obstacles that all players will face,” Courier replied. “Some players are just built to withstand them at a higher level than others; that’s part of the human condition. We’re not all alike.”

When everything is going right for her, Raducanu is unlike the others in a good way: She can seem to have the ball on a string like few others in tennis, with pinpoint precision that can pop easy winners past any opponent. But that upside proves double-edged and contributes to her perfectionism—and a propensity to panic when things aren’t going her way.

Raducanu’s most recent spin of the coaching carousel was a quick one, lasting just a couple weeks with the no-nonsense veteran coach Vlado Platenik. By some counts, he was Raducanu’s eighth different coach since her U.S. Open win.

When I spoke to Platenik this week, he said he saw significant progress from Raducanu in their limited time together earlier this month. “I really didn’t before have a player improve that much in such a short time,” he said. “She’s definitely smart and talented, but I also understand the pressure from outside that she’s getting.”

Platenik said that he appreciated the unique attention Raducanu receives after his phone began buzzing with British reporters once they started working together. But he said he was also struck by how deeply Raducanu feels every up and down along her closely watched ride. That sensitivity, Platenik believes, is because of how earnestly Raducanu wants to prove—to herself and to the world—that she can be more than the sport’s ultimate one-hit wonder.

“I honestly thought that after a few years of being in this circus, she will be a little bit more resilient to this pressure,” Platenik said of Raducanu. “But I was wrong, because she really takes it very, very serious. I think she reallllly wants it. She’s not just saying that she wants to win; she wants to do it.”

The Hopper

—CLAY Tennis on Beatriz Haddad Maia’s US Open run.

—Giri on Iga Swiatek’s loss to Jess Pegula.

—Jon Wertheim’s mailbag is full this week.

—Sara Errani and Andrea Vavasori have won the US Open mixed doubles.

—Tim Newcomb on Taylor Fritz and Asics.