The 2025 Wimbledon Shoe Report

The 2025

Wimbledon

Shoe Report

The 2025

Wimbledon

Shoe Report

Shocking news: green is a popular accent color.

Shocking news: green is a popular accent color.

By Tim Newcomb

July 3, 2025

Let’s face it: shoe fashion at Wimbledon largely comes down to the accent color. And hopefully you like green, because no matter your shade of green—here’s looking at you, “apple green” from New Balance—it’s the dominant accent to go with the all-whites of the Wimbledon 2025 edition.

The tradition of all-white attire at Wimbledon has only strengthened over time. The tournament first went “predominately in white” with its dress code in 1963. As players—or should we say brands?—have tried to defy the rules, the tournament has only doubled down, creating an even stricter version of their dress code in 1995, when “predominately” white became “almost entirely” white.

But things didn’t stop there. In 2014, The Championships included accessories in the predominantly white dress code. As per the current code, the “10-point rule” “refers to all clothing, including tracksuits and sweaters, worn on The Championship courts both for practice and for matches.” (In a rare show of flexibility, the tournament has since allowed women to wear black undershorts.)

By white, Wimbledon means white. That “does not include off-white or cream” and the back of the apparel must be “completely white.” While there’s no allowance for a solid mass or panel of coloring, Wimbledon allows a single trim of color around the neckline and the cuff of the sleeves—no wider than one centimeter, mind you—and small sponsor logos may contain colors. Accordingly, that’s exactly where you generally see dabs of color on the shoes: in the logo.

Last year’s shoes typically led with black as the main accent color with green a close second and gold a distant third. In 2025, green (think New Balance, Adidas, K-Swiss, Wilson and Novak Djokovic), and black (Asics, Nike, On, Lotto and Yonex) vied for most popular accent color, while gold (Babolat) held down a third-place role. Let’s explore some of what we’ve seen in Wimbledon footwear this year.

Coco Gauff

New Balance Coco CG2 White and Green Apple

New Balance has been crushing the footwear style game via Coco Gauff this year. We’ve seen a fun marsh green and yellow version for Australia, a “grey days” version for Roland Garros and some Miu Miu designs sprinkled in along the way. For Wimbledon, Gauff is sporting the “white and green apple” colorway of the Coco CG2. The other New Balance silhouettes will follow the colorway form—for example, Tommy Paul will be wearing the CT-Rally in the same colors—providing what the brand calls a “simple and refined design” for the grass courts.

Image courtesy of New Balance

Image courtesy of New Balance

Novak Djokovic

Asics Court FF 3 Novak

Novak Djokovic is hoping that the “24” that adorns his major tennis footwear from Asics can turn into a 25 during Wimbledon. For now, though, his Asics Court FF 3 Novak footwear includes his logo on the tongue and heel and the special 24 near the heel signifying his number of major titles. Like last season, Djokovic’s Wimbledon colorway is white with green accents, while the remainder of Asics athletes will go with white and black or silver.

Image courtesy of Asics

Image courtesy of Asics

Wimbledon Ball Kids

Babolat Jet Tere 2

Bablot may provide the most color choice across the brands at Wimbledon, with different shoe silhouettes offering differing colors, such as the blue and gold on the Jet Tere, green on the Propulse, gold on the SFX and Cam Norrie leading the Jet Mach 3 with silver accents. The Wimbledon ball kids get outfitted in Babolat each year, and in 2025 the Jet Tere 2 comes in white with gold and blue.

Image courtesy of Babolat

Image courtesy of Babolat

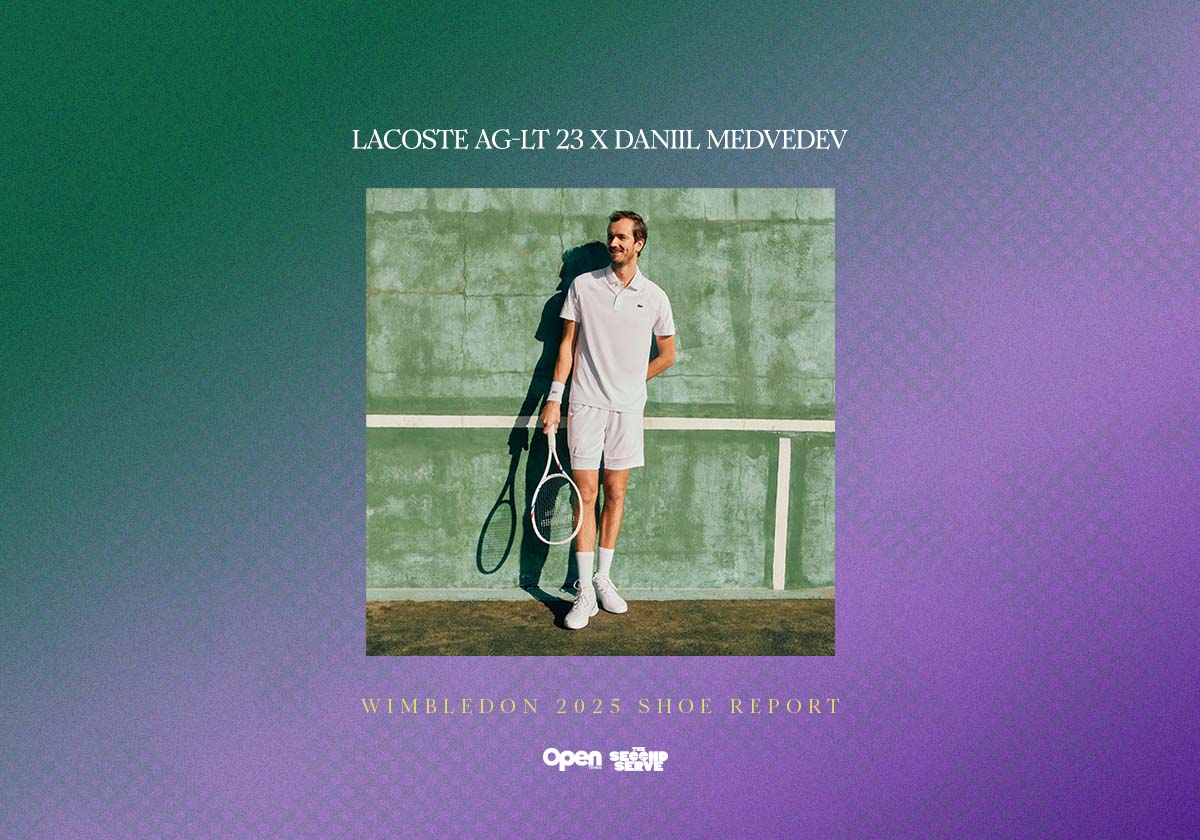

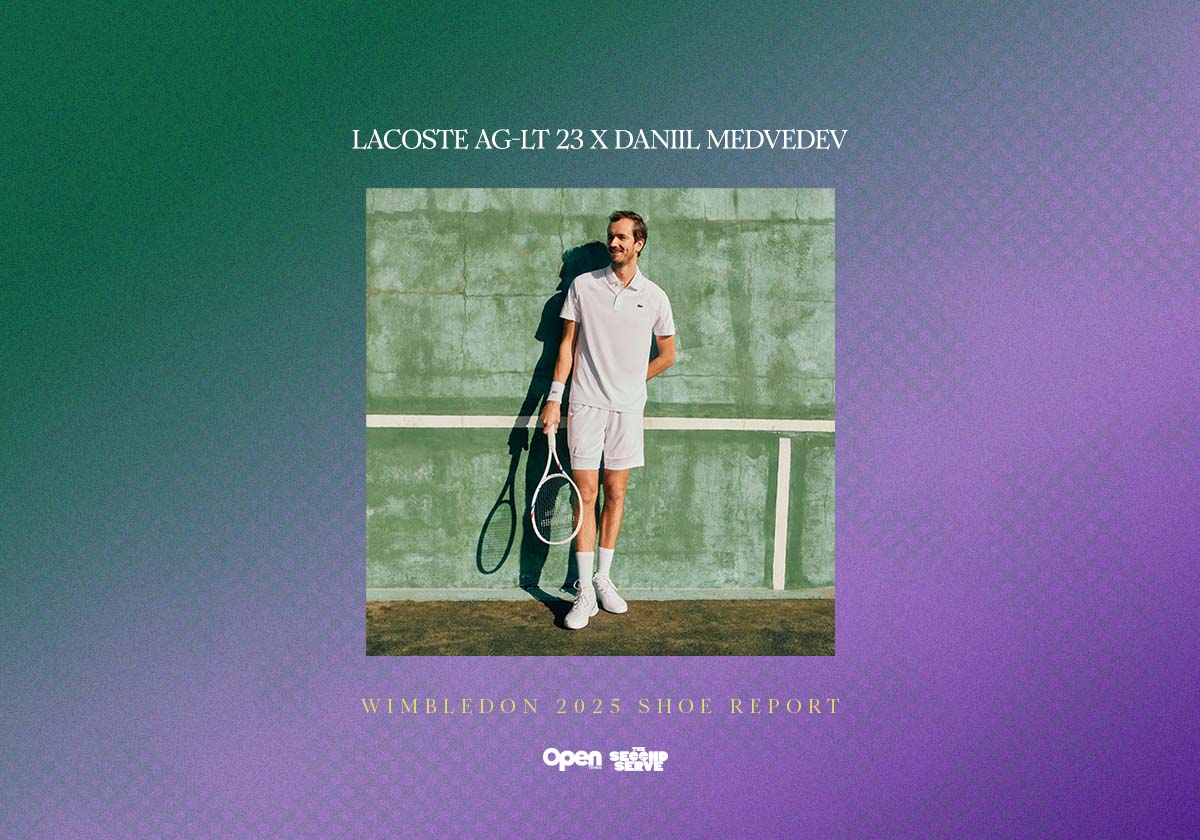

Daniil Medvedev

Lacoste AG-LT 23 x Daniil Medvedev

It was all white and black for Daniil Medvedev for the 2025 Wimbledon, which lasted only four sets for the Russian. The pinnacle Lacoste tennis performance shoe gets the player edition treatment each time for Medvedev with his gamer-inspired logo adorning the shoe (it’s also on the hem of his polo).

Image courtesy of Lacoste

Images courtesy of Lacoste

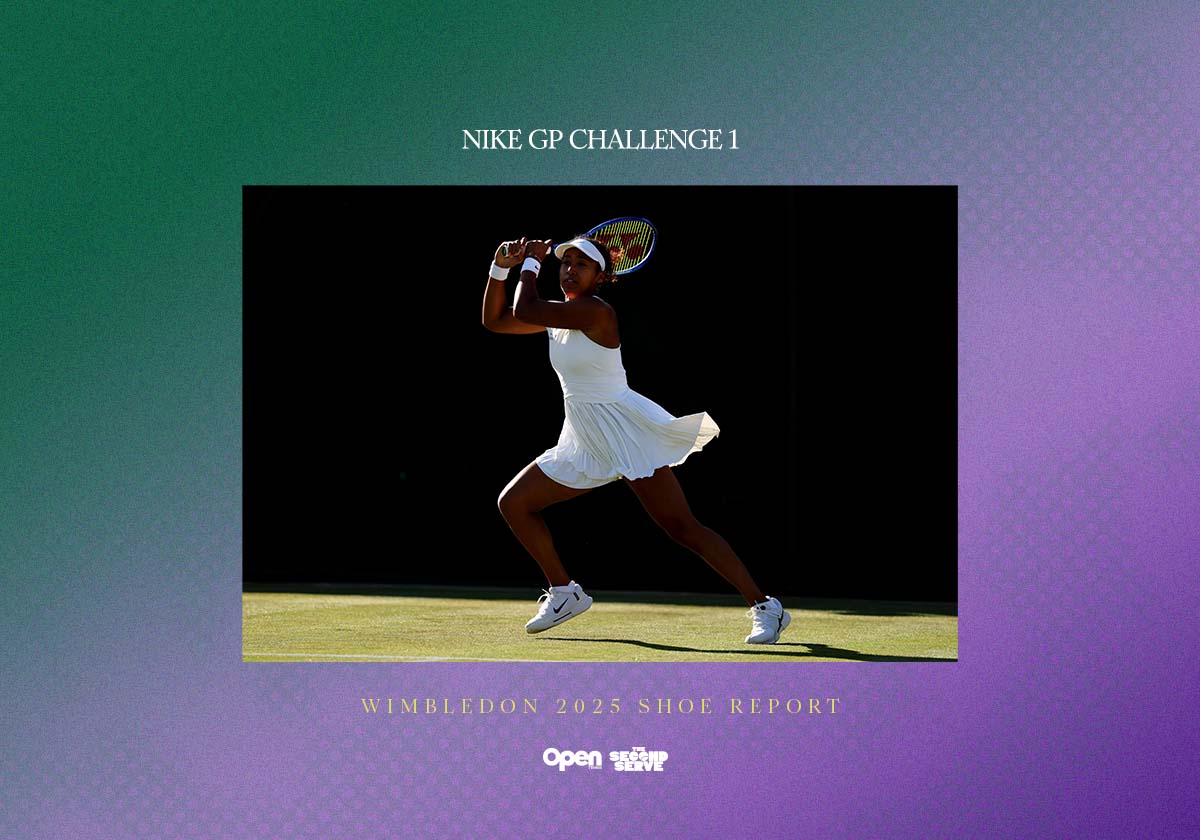

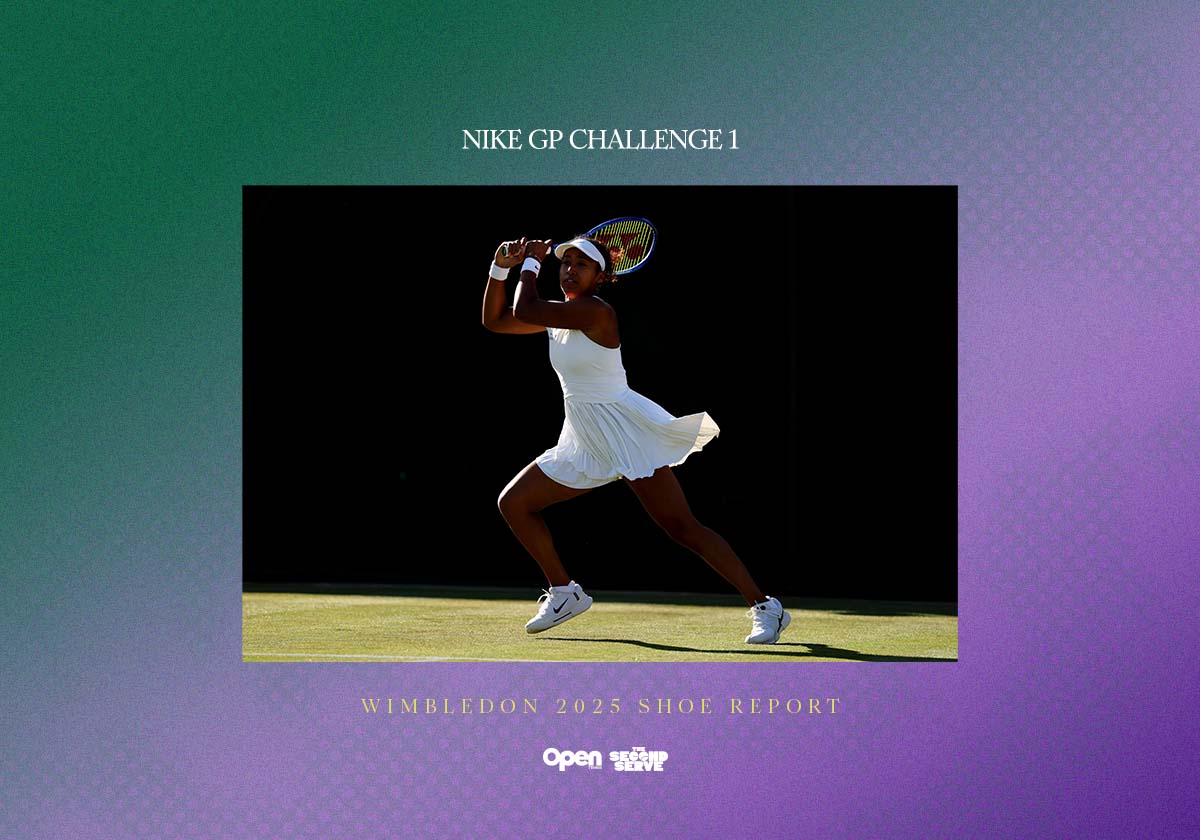

Naomi Osaka

Nike GP Challenge 1

We’ll have to wait and see if the U.S. Open offers up another Naomi Osaka flower-filled GP Challenge 1, as Osaka’s Wimbledon shoes feature black accents only, including her personalized “NO” logo on the tongue.

Getty

Getty

While adidas has made a habit of not doing anything special on the shoes for its tennis athletes, the 2025 Wimbledon colorway features green accents, as worn by some of the top players in the world (though they are paired with a handsome Originals-inspired kit).

Carlos Alcaraz had player-edition shoes for Wimbeldon 2024 and even some unique Alcaraz-specific logos on his Nike shoes for Roland Garros just a few weeks ago, but his Wimbledon shoes remain void of the special treatment, sticking with the white and black the brand chose for this year.

Getty

Aryna Sabalenka, who had a tiger logo on both her Australian Open and Roland Garros shoes, was void of anything special for Wimbledon 2025, except for the fact she’s still playing in the discontinued Nike Zoom Nxt (she did have special-edition bags from both Wilson and Nike, with the Nike version featuring a cool tiger logo).

On continues to outfit Iga Swiatek, Ben Shelton and Joao Fonseca. On doesn’t create special designs for each player, and this year’s Wimbledon looks went white and black.

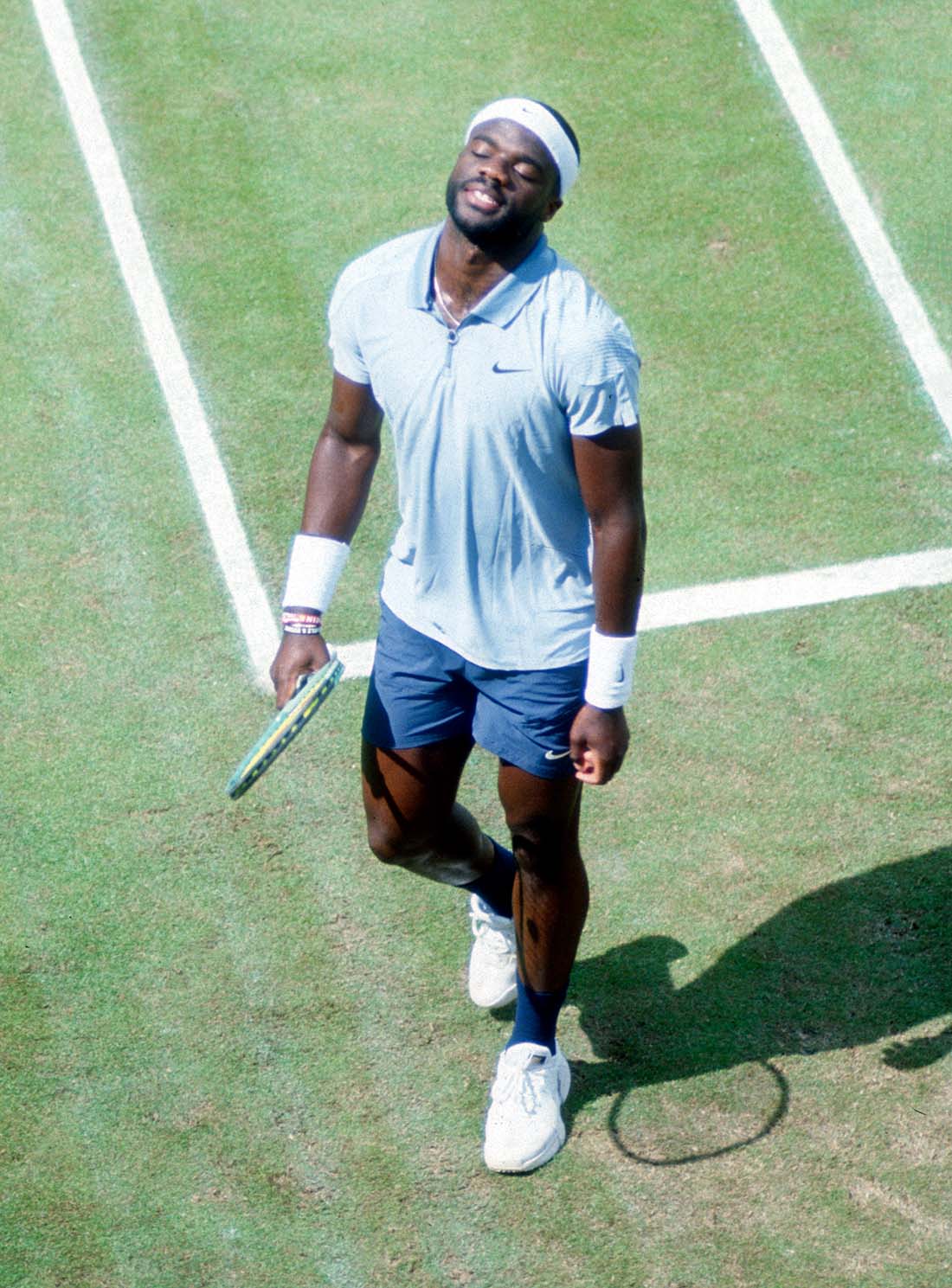

A pair of Lululemon athletes—Frances Tiafoe and Leylah Fernandez—don’t have shoe deals and are wearing K-Swiss for Wimbledon, with white and black and white and green the options for the players. The new K-Frame Speed Rublo designed in partnership with Andrey Rublev is also in play. Tiafoe does not have a deal with a footwear brand, but has worn K-Swiss since switching to Lululemon ahead of the Australian Open. Fernandez, also a sneaker free agent, has been wearing her dad’s unreleased Aesem Athletica brand for all tournaments in 2025, except on the grass.

Yonex athletes typically get special treatment with their name and country flag adorned on their sneakers. This Wimbledon, most Yonex athletes will don a white and black version of the Eclipsion 5.

Follow Tim Newcomb’s tennis gear coverage on Instagram at Felt Alley Tennis.

SIGN UP — YOU'RE ONLY AS GOOD AS YOUR SECOND SERVE.

High Horse

High Horse

High Horse

When the All England Club faced the monster under its bed.

When the All England Club faced the monster under its bed.

By Lydia Horne

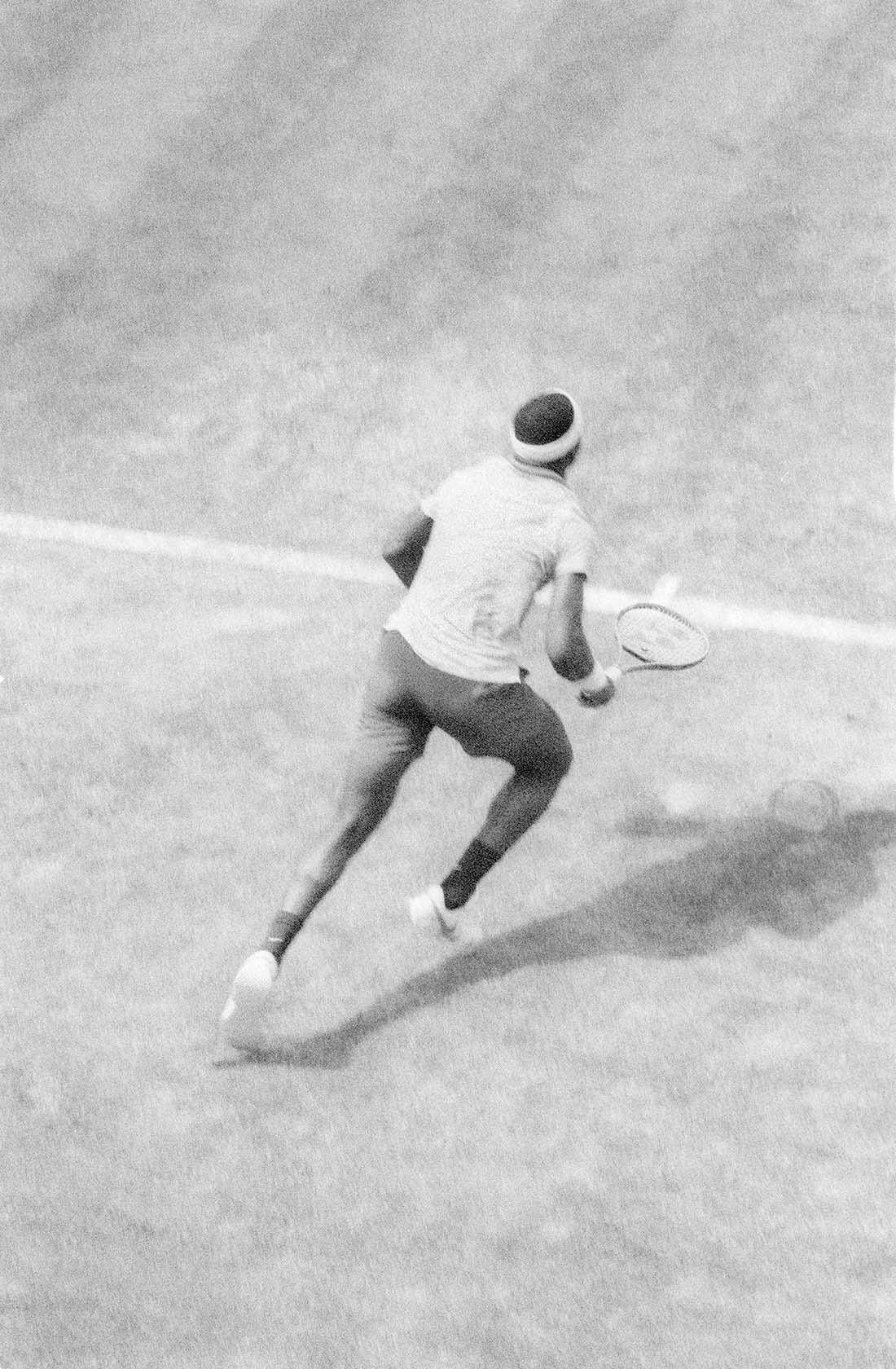

Photography by Tom Parker

Featured in Volume 1 of OPEN Tennis — BUY

High Horse

High Horse

When the All England Club faced the monster under its bed.

When the All England Club faced the monster under its bed.

By Lydia Horne

Photography by Tom Parker

Featured in Volume 1 of OPEN Tennis — BUY

A Wimbledon umpire turns their neck at least 280 times in a match. Along with routine humiliation from athletes with incredibly short fuses, add chafing to the list of occupational hazards.

For almost 130 years, the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club (aka AELTC, Wimbledon’s governing body) took the same approach to their officials’ uniforms as Edwardian parents did to their children: better seen than heard. And best seen at a distance. Uniforms were often the same color as Har-Tru: a powdery bluish-green that did no more for the appearance than did the shapeless blazers and ankle-length skirts. The ball boys, line judges, and umpires were supposed to blend in with the court surface. AELTC even instructed clothing manufacturers to use only dull vintage buttons because the glint off a freshly polished disc could distract a player in a decisive moment.

And so Wimbledon officials muddled on, in their ancient buttons, until a decidedly non-British, non-tennis-playing entrepreneur accessed (and accessorized) the tournament’s brand power. Ralph Lauren, who became the official Wimbledon outfitter in 2006, distilled the all-grass, all-white, all-English club into a newly refined look. It was a win for both AELTC and the designer. Within the pantheon of Ralph Lauren’s attainable luxury lifestyles—including safari, cowboy, yacht—the pedigree-obsessed American designer added strawberries and cream. By elevating the appearance of the rank and file, Ralph Lauren transformed employees’ attire from mandatory uniforms to badges of honor that conveniently function as walking advertisements for the brand.

Wimbledon is frozen in amber: It’s averse to late nights (11 p.m. curfew), warm tennis balls (cans are chilled in a fridge at 68℉), and self-expression (mandatory whites). Until the 1920s, women were expected to wear corsets while competing, the undergarments often bloodied at the end of a grueling match. Similar restrictions—especially for female players—have only recently relaxed: In 2023, AELTC finally allowed women to wear colored shorts under their skirts and dresses. It’s therefore unsurprising that the organization is also prudent about advertising; AELTC discourages overt advertising on the grounds and large logos on player clothing. Their few sponsors are reputable brands with whom they share a long relationship: Rolex became the official timekeeper of the tournament in 1978. Slazenger and Wimbledon have the longest-running sports sponsorship in history. (113 years and counting.)

Between 1990 and 2010, AELTC more than doubled the number of sponsors of the tournament. IBM, Lanson, HSBC, Evian, and Ralph Lauren. While Wimbledon still had relatively few sponsors compared with the other Grand Slams, these partnerships showed demonstrable interest in commercialization and represented AELTC taking a baby step toward facing its monster under the bed: change.

But before Ralph, there was Wood Harris. A leading U.K. manufacturer of uniforms for the hospitality industry, Wood Harris was selected by AELTC to be the official Wimbledon supplier in 2000. Then-owner Nick Jubert was the third generation to manage the family company. The original Wood Harris factory in Northern Ireland, run by Jubert’s grandfather, remained open during the Troubles. The opportunity to outfit Wimbledon’s on-court staff was yet another defining moment in the manufacturer’s history—as well as a challenge: The designs for the officials’ uniforms were more than 10 years old and in desperate need of updating.

Jubert and his team started their research at qualifiers in Eastbourne. While the audience had their eye on a Russian teenager named Anna Kournikova, the Wood Harris contingent watched the umpires and line judges, who appeared particularly uncomfortable in their stiff clothing as a heat wave pushed temperatures past 80 degrees. Wood Harris and AELTC settled on 14 garments, including a long green jumper with gray and white Chiclet-shaped speckles for female line judges, polyester blazers with khaki pants for umpires, and green collared shirts with matching green thigh-high shorts for the ball boys and girls. Wood Harris’ clothing used a stretch fabric that introduced freedom of movement.

While Wood Harris’ costumes were more contemporary, they were still short of anything stylish. AELTC’s color palette of purple and green—suggested by their longtime sponsorship managers at IMG screamed court jester, not racquet sport. But the club appeared unconcerned.

In 2006, Jubert received a call from an AELTC representative: Wimbledon would no longer be requiring Wood Harris’ services. It was hardly a surprise; other Grand Slams used uniforms as an opportunity for sponsorship. AELTC had to admit Wimbledon’s commercial value. And none too soon: In March, AELTC announced a five-year contract with U.S. fashion house Ralph Lauren, who bought the rights to outfit all 570 umpires, ball girls and boys for just under $10 million.

The transition was quick. AELTC paid Wood Harris for their remaining stock, and then said goodbye. Although defeated, Jubert and his team soon landed a new reputable British client: King Charles III.

"Canadian Doubles." / MGM Studios

Alex Crockford was 16 when he was selected from more than a thousand aspiring ball boys and girls (BBGs) to serve the Championships. The rigorous training program began four months before Wimbledon’s opening day. A few times a week, about 250 teens from local secondary schools performed wind sprints and ball-rolling exercises on the AELTC grounds. They practiced standing still for long periods of time—sometimes with arms extended overhead—in preparation for long rallies. Years later, one former BBG would compare these drills to his RAF cadet training.

The 2006 tournament was Crockford’s second run as a ball boy. He knew which players liked to towel off between games or maniacally bounce the ball before serving. But this year was different: His green kit was replaced with a sharp blue rucksack. Inside were several pairs of navy T-shirts with hidden mesh panels to help with ventilation, shorts that skimmed the knee, white socks, and a tracksuit for chilly mornings. The two thin green stripes on the shirt collar and championship’s emblem on the sleeve were the only reminders of uniforms past. Now the stitched silhouette of a polo player on horseback—the Ralph Lauren logo—charged across Crockford’s left breast, taking three inches of prime real estate.

Senior court officials were made over too: line judges in navy blazers with white piping over collared button-downs. Umpires in fully lined pin-striped blazers with wide-legged trousers and bias cut skirts. White newsboy caps and Ralph’s signature ties. Men’s clothing designer and Ralph Lauren biographer Alan Flusser remembers the early rounds of the 2006 championship. “I think the first impression was, ‘Who the hell did those clothes?’ All the ball boys and girls and referees looked like they belonged there.”

On opening day, just a few courts over from where Crockford raced after the ball, Bethanie Mattek-Sands appeared for her first-round match against Venus Williams.

Mattek-Sands was known for pushing the fashion envelope. As a junior player, she would wear her aunt’s handsewn creations: graphic skirts, windbreaker sets, and shirts with colorful patches. Over the years, her style was somewhat tempered by sponsors with specific ideas about what she should wear on the court. But Adidas dropped Mattek-Sands as a spokeswoman before the 2006 Wimbledon Championships, and she arrived in London without a pre-appointed look. Scrambling, she made a last-minute trip to Harrods. Mattek-Sands walked onto Centre Court wearing white knee-high socks, a tube top over a tank top, chandelier earrings, and tiny shorts.

Commentators were confused by Mattek-Sands’ wardrobe choice—was she competing in Wimbledon or the World Cup? Andy Murray’s mother told reporters that she would make her son change if he ever wore something like that. To make matters worse, Mattek-Sands was outdressed by tournament officials. The bottom of the chair umpire’s trousers had a crisp pleat. The BBGs were stamped several times over with the Polo logo. “I felt like Wimbledon was really saying we’re posh, we’re dressy, we’re classy. We’re preppy, we’re conservative,” says Mattek-Sands. “A lot of words that maybe didn’t describe me.”

Mattek-Sands has a framed photo of herself from that match. In it she’s walloping a forehand in compression socks and a sweatband. In the background, a female line judge is bending over in a Ralph Lauren striped button-down and a khaki skirt. Mattek-Sands only got one game off Venus that day, but her soccer-inspired outfit won the long game. Shortly after the match, officials approached Mattek-Sands. She thought she was going to get fined for her outfit. Instead, they asked for her socks; AELTC wanted to display them in the prestigious Wimbledon Lawn Tennis Museum.

As a teenager in the ’60s, Ralph Lauren (née Lifshitz) taught athletics at Camp Roosevelt in the Catskill Mountains. According to Flusser’s 2019 biography Ralph Lauren: In His Own Fashion, Lauren was enamored with the private school campers, those young men who considered “summer” a verb and would return to the halls of Groton in the fall. This exposure inspired Lauren’s lifelong fascination with blue-blood culture despite never attending an Ivy League school or having family money himself.

Since Lauren couldn’t always play the part, he would look the part. Early in his career, Lauren, an avid jogger, recognized the link between exercise and youthfulness. This was reinforced in the late ’80s, when the country’s fitness obsession and a personal health scare (benign brain tumor) propelled Lauren—quite literally—into motion. In 1992, Ralph Lauren debuted Polo Sport, a line of performance-driven activewear, in the same year as the Barcelona Summer Olympics. Polo Sport quickly became one of the brand’s most valuable collections, beloved by workout junkies as well as hip-hop and skateboard communities.

“There is just an attractiveness about athletes in general,” Lauren said in a 1993 New York Times interview. “Athletic clothes say that people have energy.”

In 2005, Lauren signed a partnership with the US Open to outfit all on-court ball persons and officials. Tennis neatly fit in the world of Ralph Lauren-approved leisure activities for the gentile class and gentile wannabes. Never mind that Lauren barely knew a slice from a drop shot.

In his 1984 bestseller What They Don’t Teach You at Harvard Business School, IMG founder Mark McCormack describes pitching Wimbledon as a conservative investment to advertisers. McCormack writes, “Wimbledon does not have to win tournaments to maintain visibility, and it won’t retire.”

This logic aligned with Lauren’s business interests—he’d been trying to break into the hard-to-reach European market for years. Some progress had been made: In 1981, Lauren opened his first store outside of the United States on London’s tony New Bond Street. Located in a former pharmacy, the Ralph Lauren shop was the first freestanding shop in Europe for an American designer. London was a natural home for Ralph. The city and the designer shared an affinity for tradition and wood mallards.

In spring 2006, AELTC appointed Ralph Lauren over British brands, including Burberry and Aquascutum, also vying for the job. In a statement to the press, former Wimbledon marketing director Rob McCowen explained that Ralph Lauren’s discretion was appealing: “They don’t have big logos all over their shirts.” Evidently McCowen did not appreciate that, while Ralph Lauren shared design sensibilities with the British, his approach to branding was unmistakably American.

Ralph Lauren initially designed a collection of all-white uniforms. An early mistake. AELTC pointed out that all-white would make it challenging to differentiate between players and officials, and sent designers back to the drawing board.

To determine how to integrate color and pattern, Lauren referenced archival photos of Oxford and Cambridge University students playing tennis. Lauren already frequented college campuses: Princeton University was famously a breeding ground for preps (and thus a source for inspiration). Lauren decided that his essential collared shirt would be the Wimbledon collection’s mainstay. The short-sleeved collared shirt was originally designed by French tennis star Jean René Lacoste, who wore it during his consecutive US Open wins in 1926 and 1927. Ralph Lauren repopularized the three-buttoned shirt in 1972, presenting his version as a classier, smarter alternative to Lacoste and the polyester athleticwear that was trendy at the time. He changed the name while he was at it—goodbye tennis shirt, hello Polo—and replaced the alligator with a horse.

Lauren has been accused of stealing designs from the Brits (and others) for years, and he still demonstrates some disregard for provenance. In a 2023 interview for the Financial Times that was conducted on Lauren’s 17,000-acre property in Colorado, Lauren said, “I don’t care if a thing is English, French, antique or modern. It’s whatever appeals to my eye. It’s what works. I just care if it tells a story.” Evidently, his story is a bestseller: The brand currently has 23,000 employed worldwide and announced nearly $6.4B in revenue in 2023.

Podcaster Avery Trufelman, whose series Articles of Interest: American Ivy tracked the evolution of prep, isn’t too concerned with appropriation claims: “What’s more American than stealing from the British?”

The Wimbledon uniforms capture Ralph Lauren’s multicultural influences. There’s British aristocracy, vintage tennis, Ivy League culture. But ultimately, the look is self-referential—and aspirational: Ralph Lifshitz is wearing Ralph Lauren. A Jewish boy from an immigrant family in the Bronx, who first glimpsed the good life teaching gym to privileged campers, recognized a kinship with tournament staff. By elevating their look, he elevated his past.

“Ralph stormed the country club,” Trufelman says. “And he’s let us all in there with him.”

SIGN UP — YOU'RE ONLY AS GOOD AS YOUR SECOND SERVE.

Kith and Wilson are Back with Their Third Collaboration

Kith and Wilson are Back with Their Third Collaboration

Kith and Wilson are Back with Their Third Collaboration

Vast collection brings a “London to New York” feel.

Vast collection brings a “London to New York” feel.

By Tim Newcomb

June 17, 2025

Images courtesy of Kith and Wilson.

Images courtesy of Kith and Wilson.

Keep your voices down for the release of the Kith for Wilson 2025 collaboration this Friday. The third effort between the two brands—each release has happened in the summer of an odd year, starting in 2021—extends from on-court apparel for men and women, plus high-performance racquets and off-court apparel, including the early launch of a “Quiet Please” graphic tee.

A fan of tennis, Kith owner Ronnie Fieg first joined with Wilson in 2021. They didn’t do things small, launching more than 100 items. Then, in 2023, they did it again. And the 2025 launch extends the more-is-more approach.

The on-court collection includes polos, shorts, tees, outerwear, cardigans, dresses, sports bras, and skirts, many of the items in matching colorways. Throughout the array, expect “rich green, blue, and white hues in solid, striped, and color-blocked iterations” with custom co-branded logos from the two companies. A tee reading “London to New York” highlights the classic green and blue that anchor the designs. Accessories abound, with everything from headbands to caps. Off court, the lifestyle capsule updates signature Kith designs with tennis-inspired artwork, dripping in green and white. The collection features outerwear, vests, polos, Henleys, crewnecks, tees, shorts, sweaters, a blazer, socks, towels, a canteen, and the “Quiet Please” graphic tee.

To add equipment to the mix, the brands will again release co-branded tennis balls (in two colors), racquet covers, backpacks, totes, and a leather racquet bag. The latest versions of the Wilson Pro Staff 97, Blade 98, and Shift 99 all get original Kith designs, playing heavy in greens and whites. Kith for Wilson 2025 may ask for quiet, but the sheer volume of product is anything but.

Images courtesy of Kith and Wilson.

Images courtesy of Kith and Wilson.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

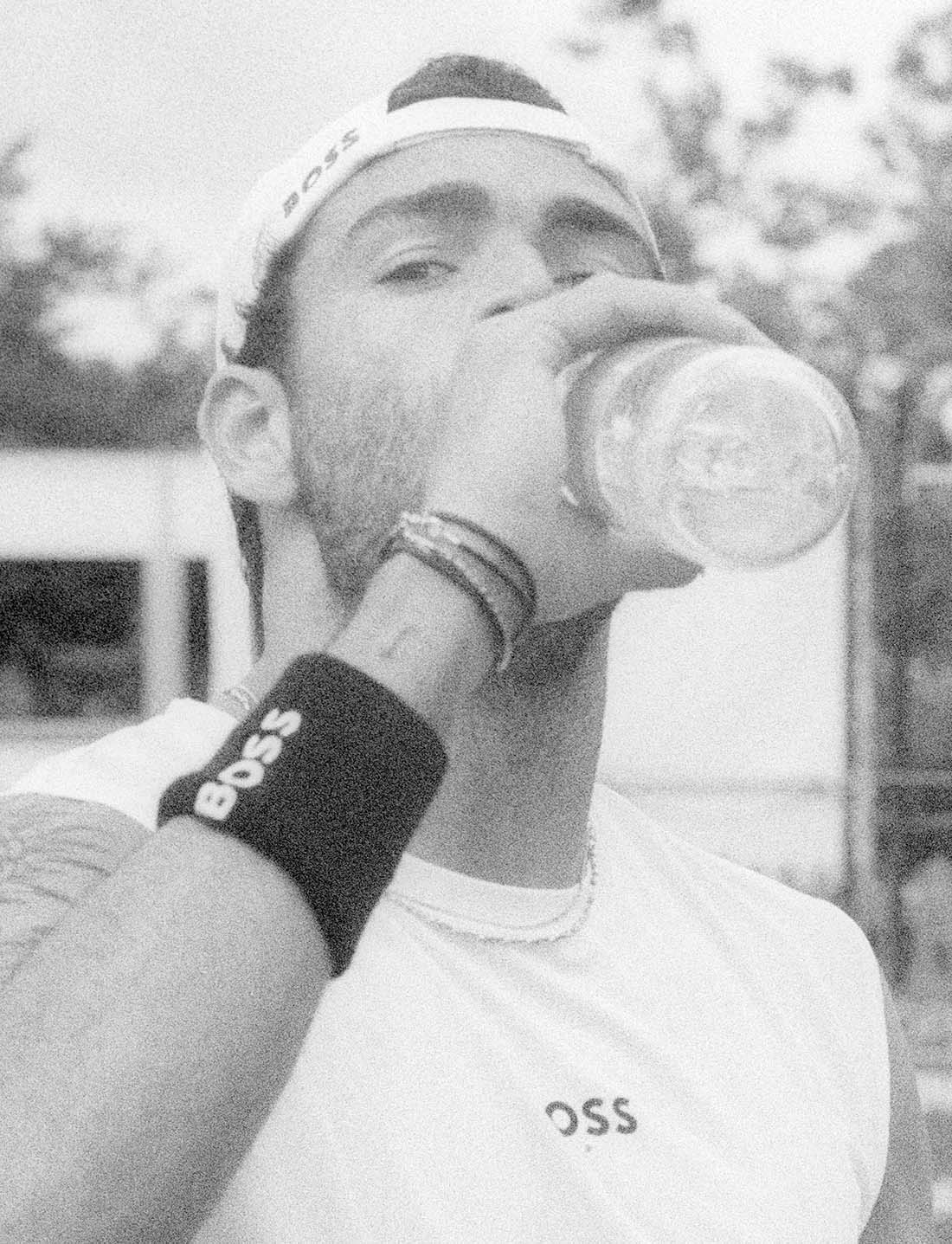

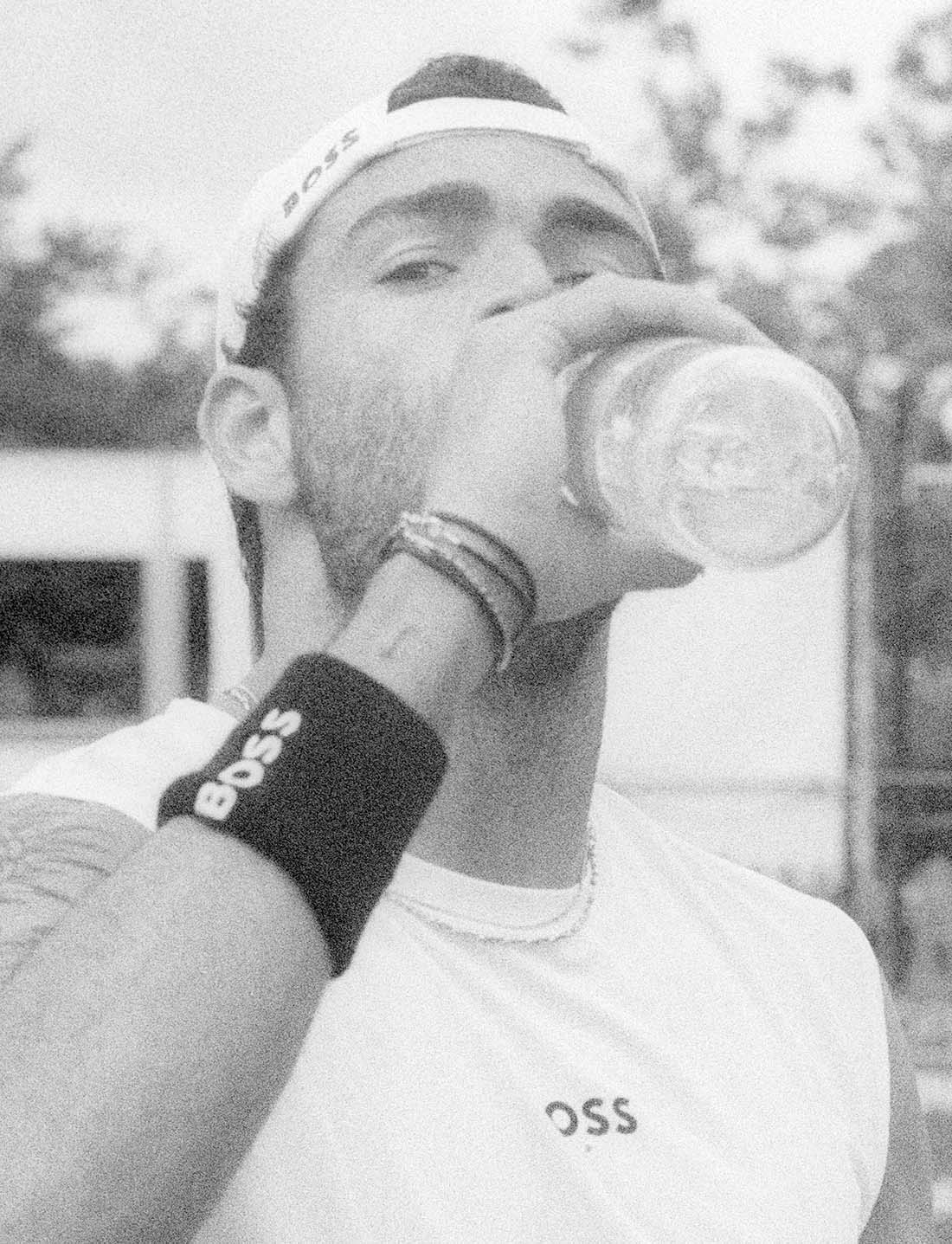

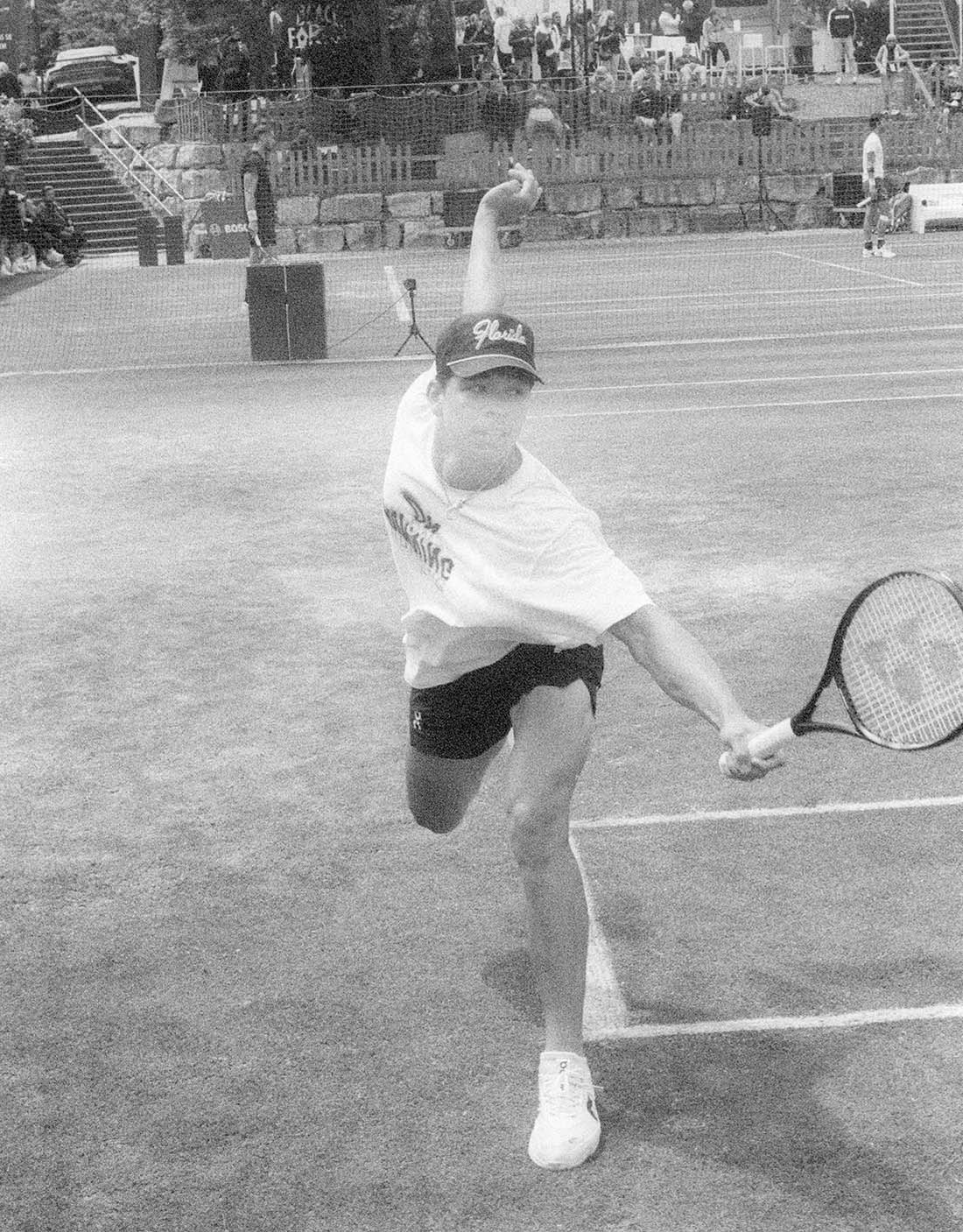

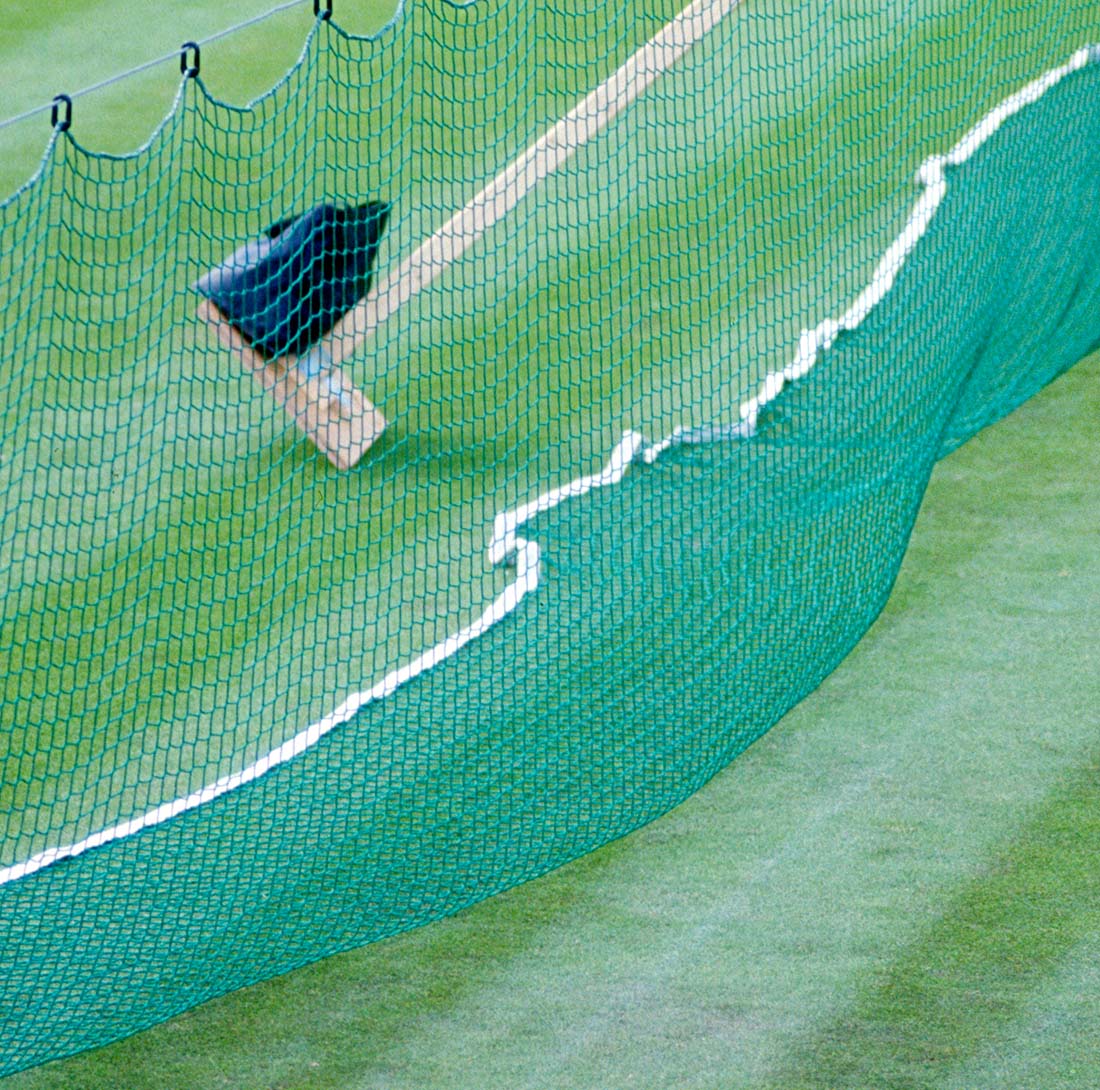

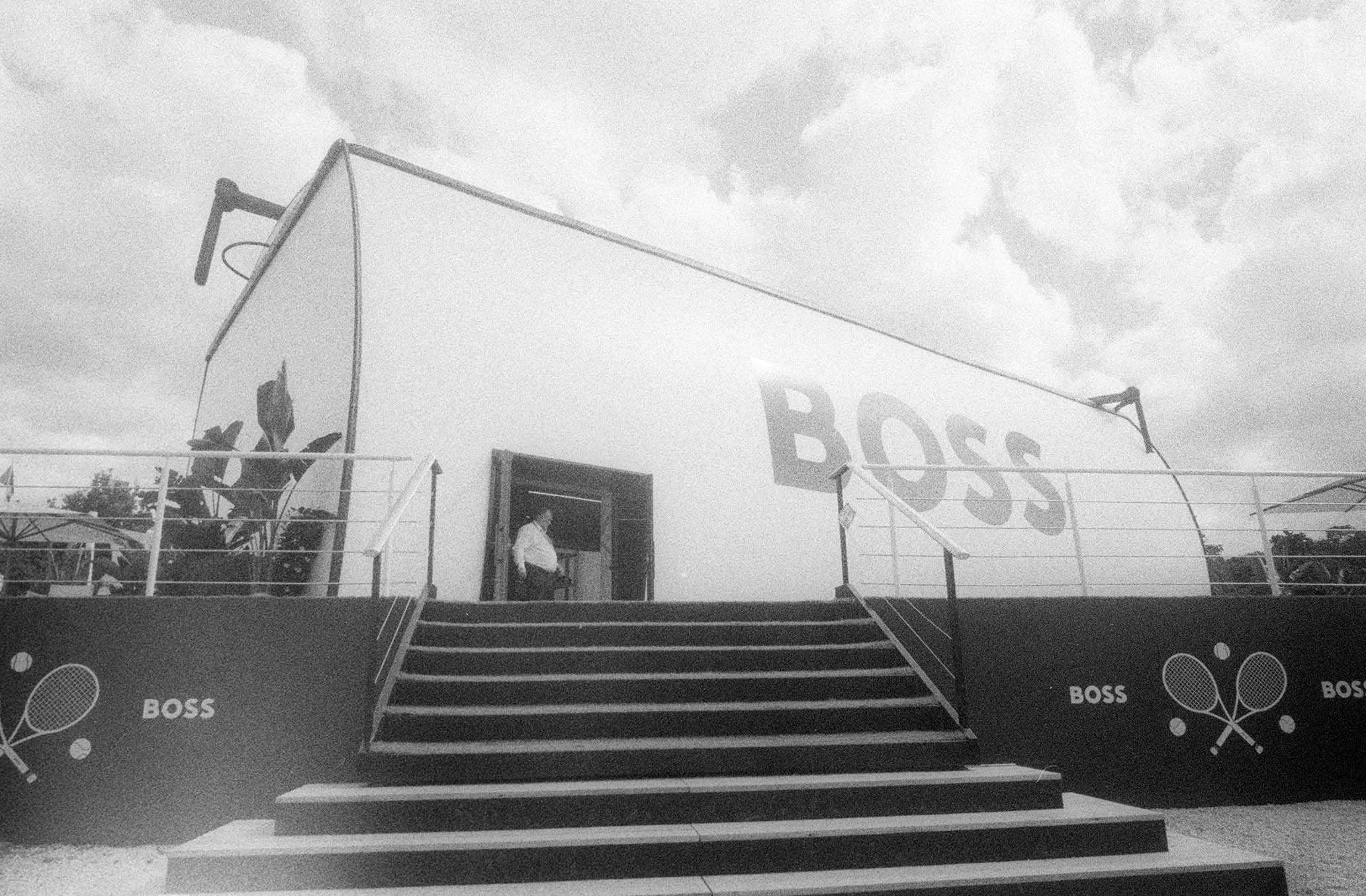

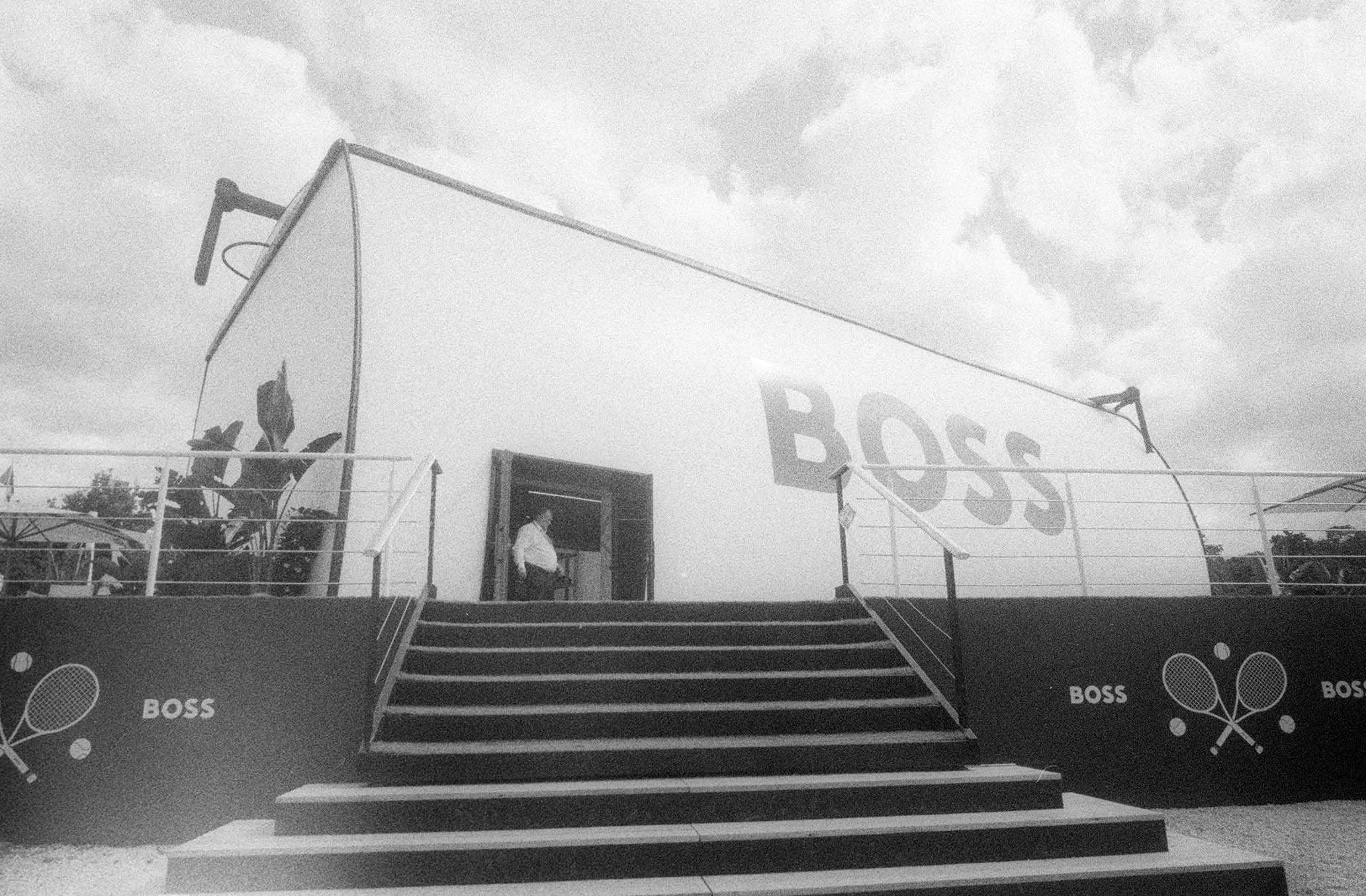

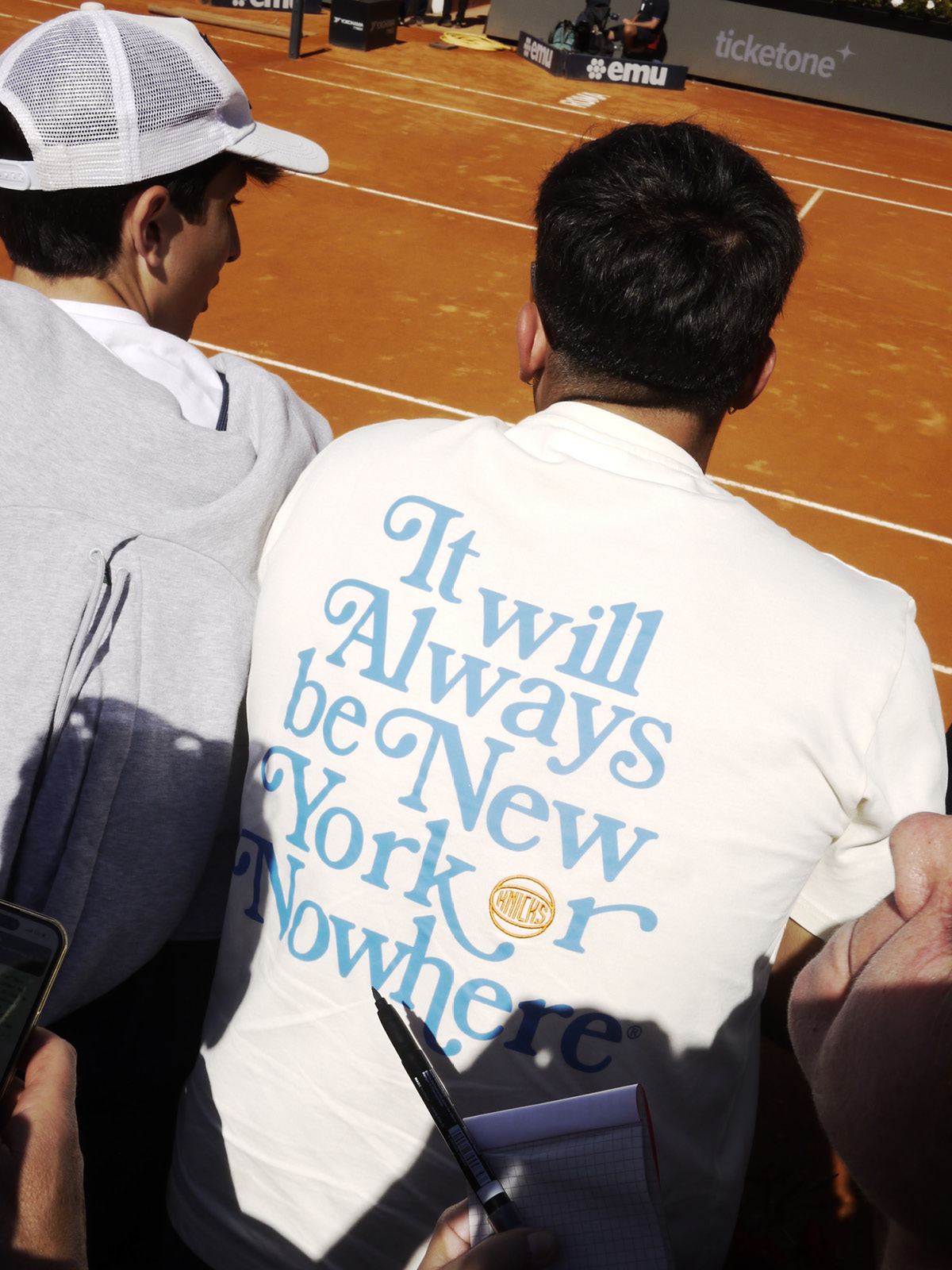

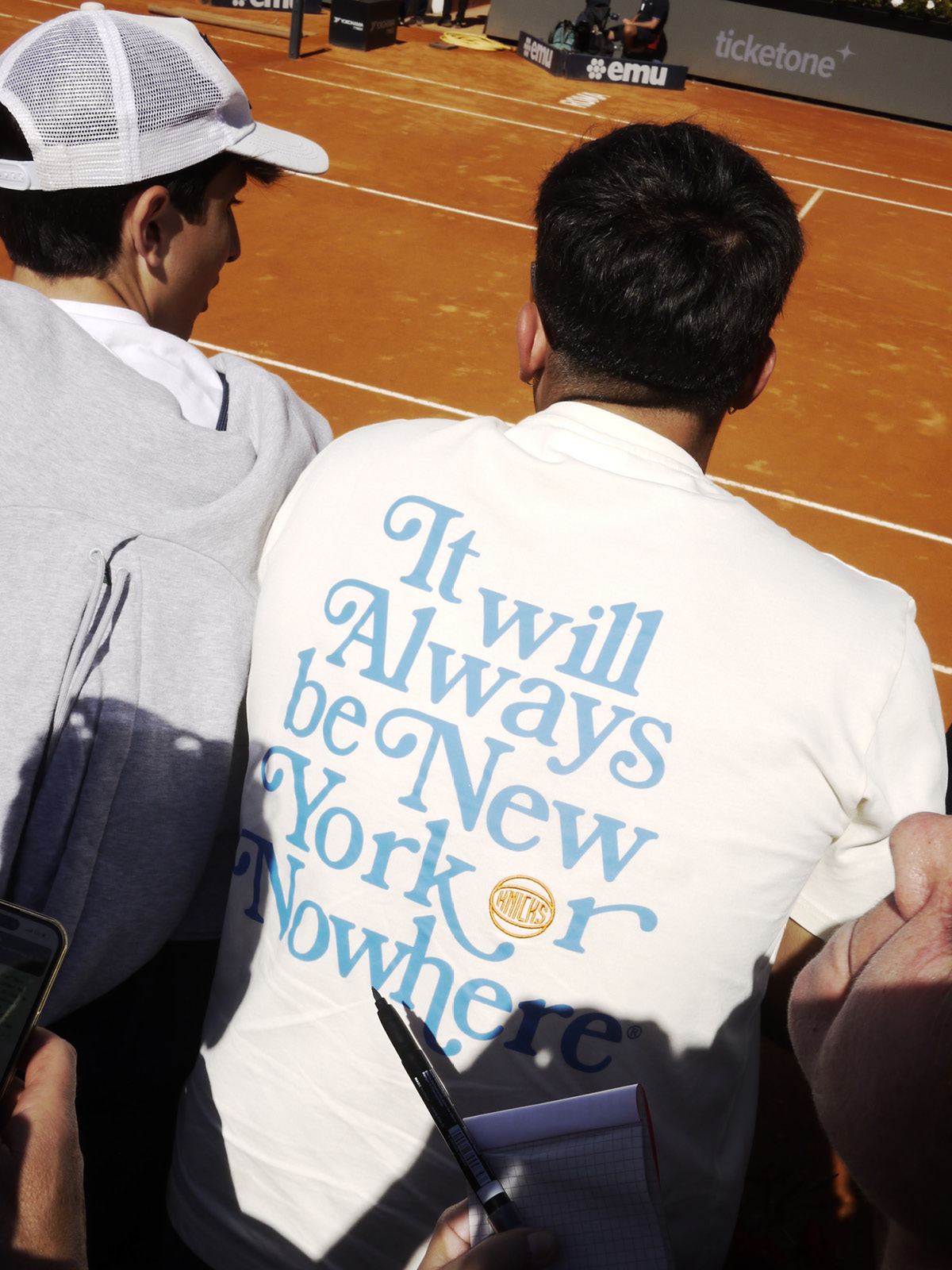

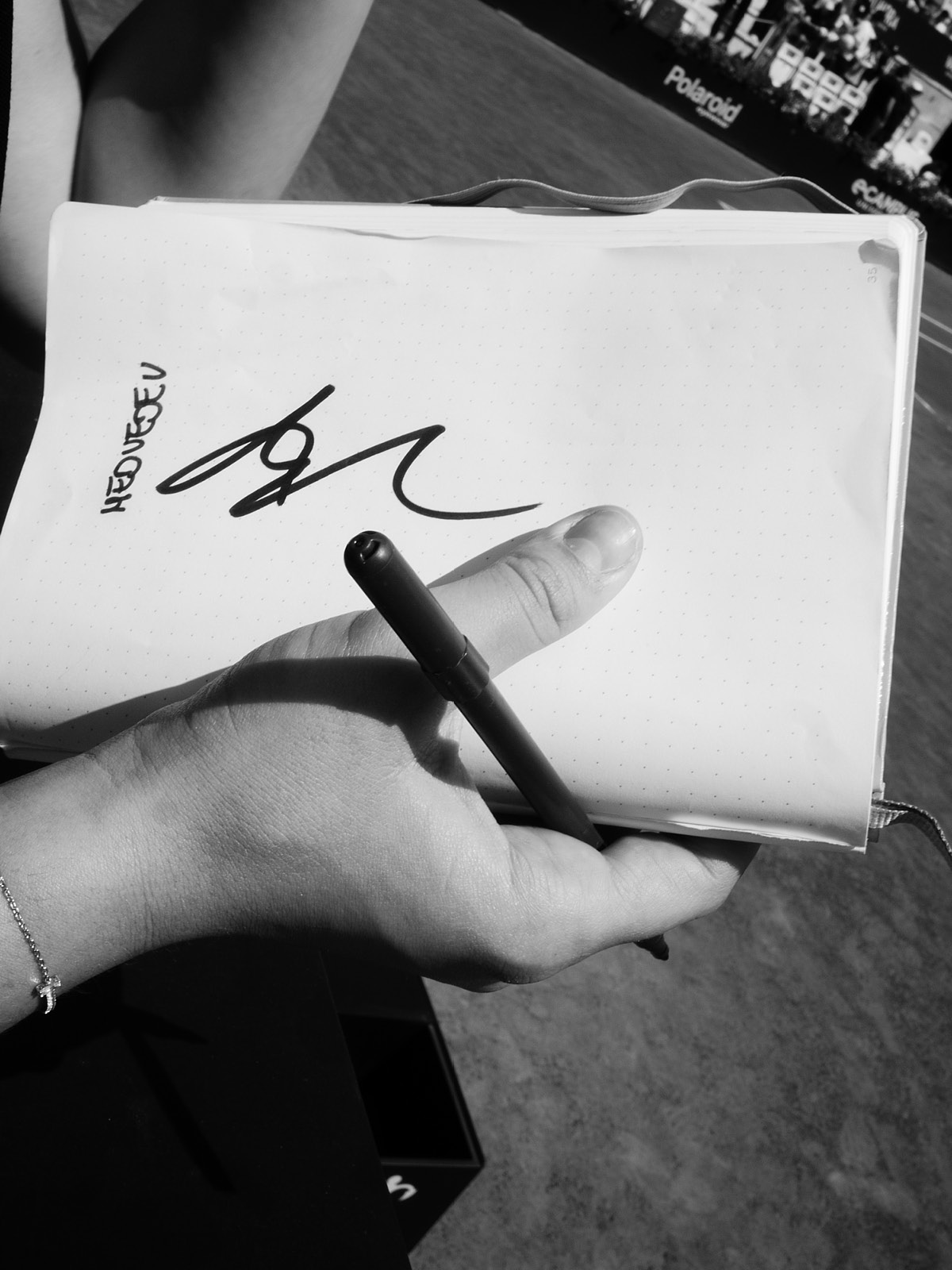

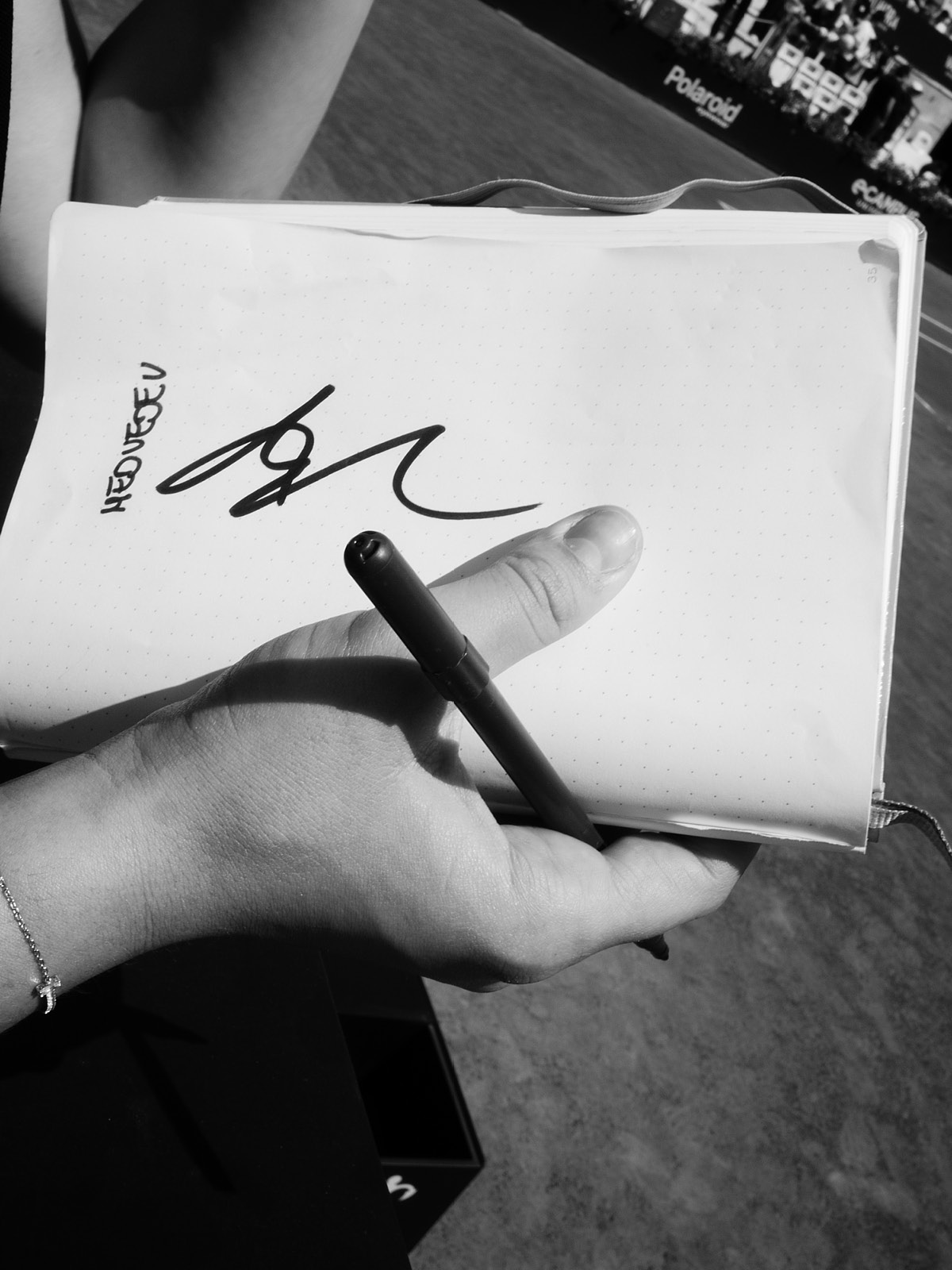

Boss of Bosses

Boss fo Bosses

A look back at the 2024 Boss Open, as featured in

OPEN Tennis Volume 1.

A look back at the 2024 Boss Open, as featured in

OPEN Tennis Volume 1.

Photography by Marcelo Gomes

Featured in Volume 1 of OPEN Tennis — BUY

Boss of Bosses

Boss of Bosses

A look back at the 2024 Boss Open, as featured in

OPEN Tennis Volume 1.

A look back at the 2024 Boss Open, as featured in

OPEN Tennis Volume 1.

Photography by Marcelo Gomes

Featured in Volume 1 of OPEN Tennis — BUY

SIGN UP — YOU'RE ONLY AS GOOD AS YOUR SECOND SERVE.

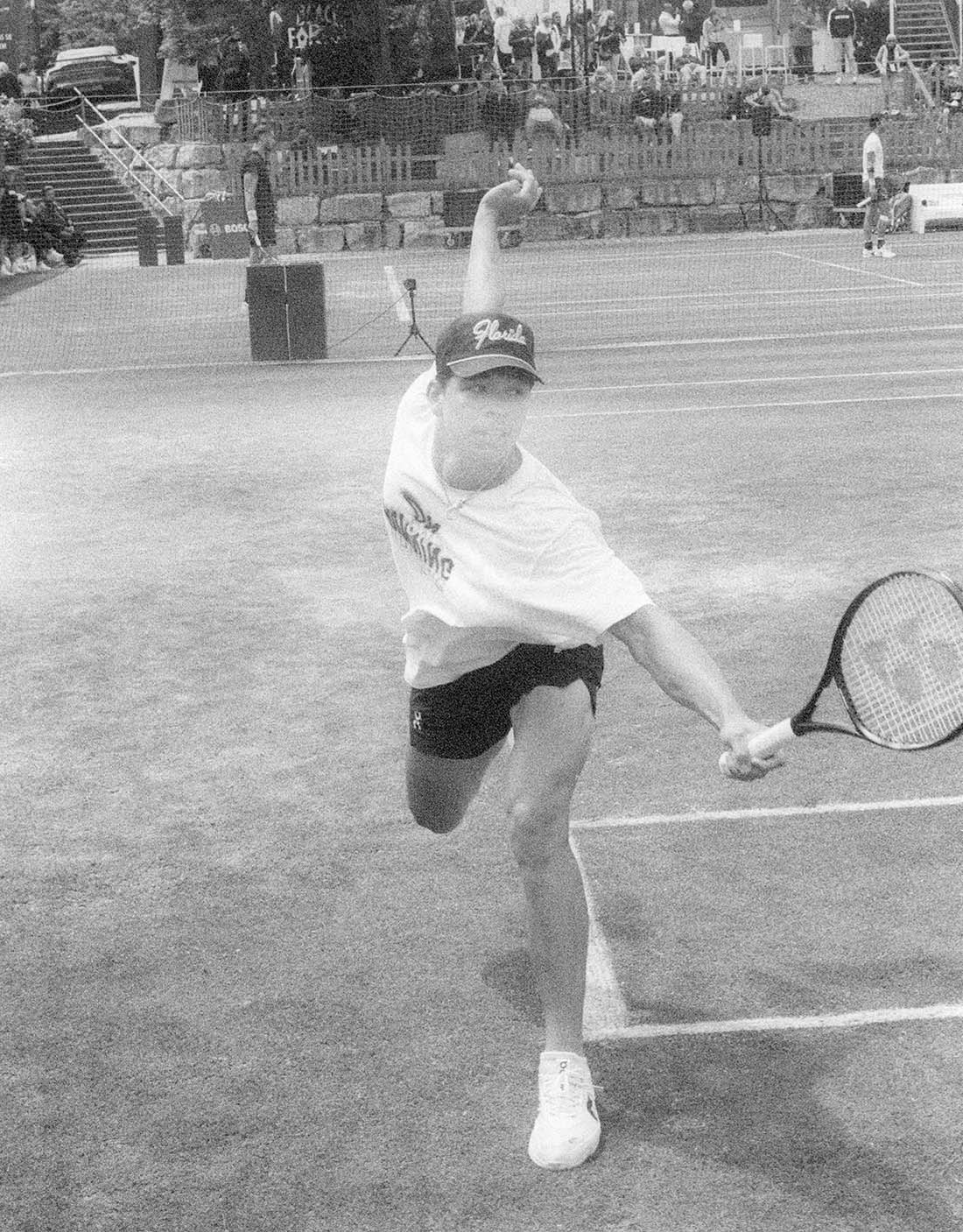

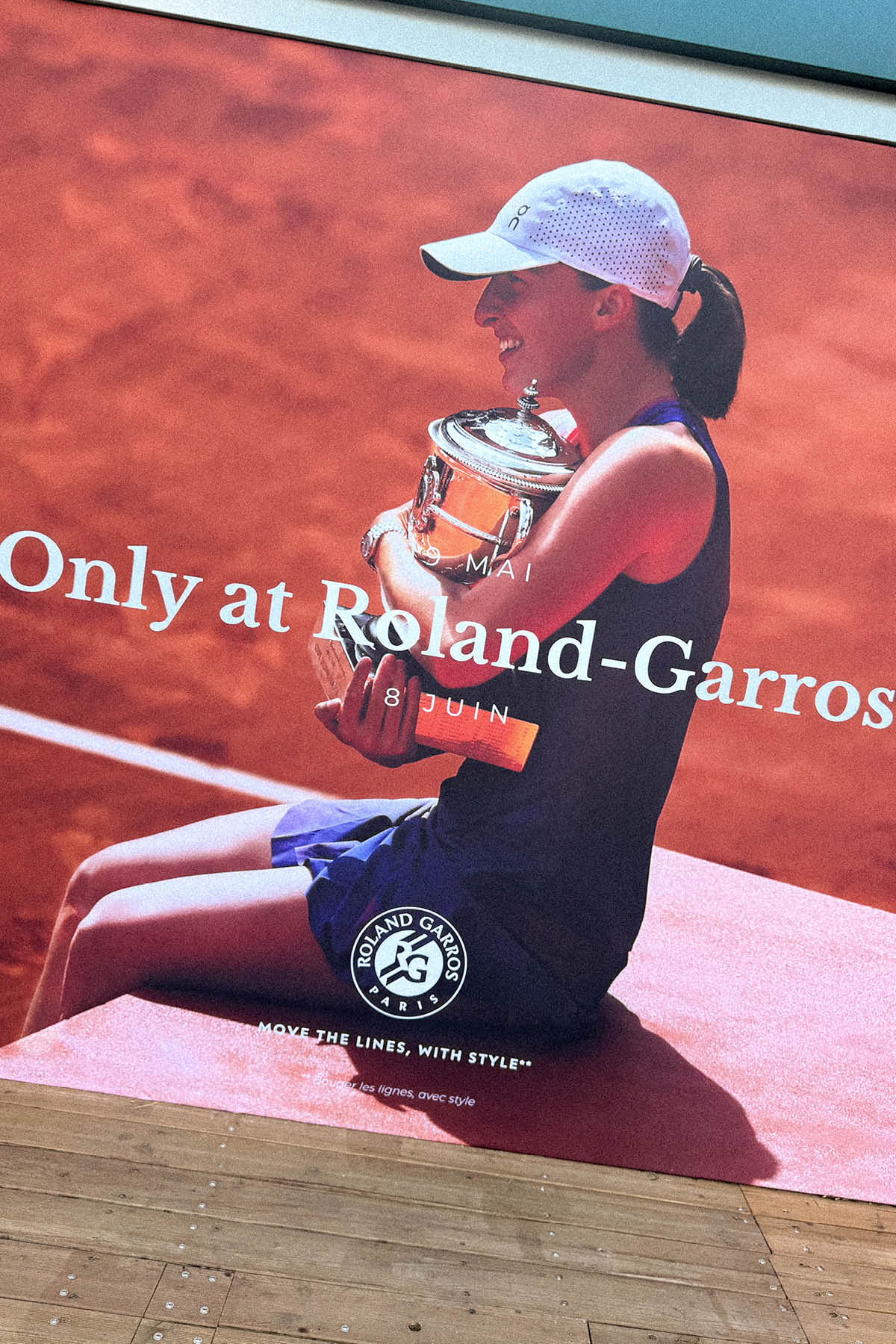

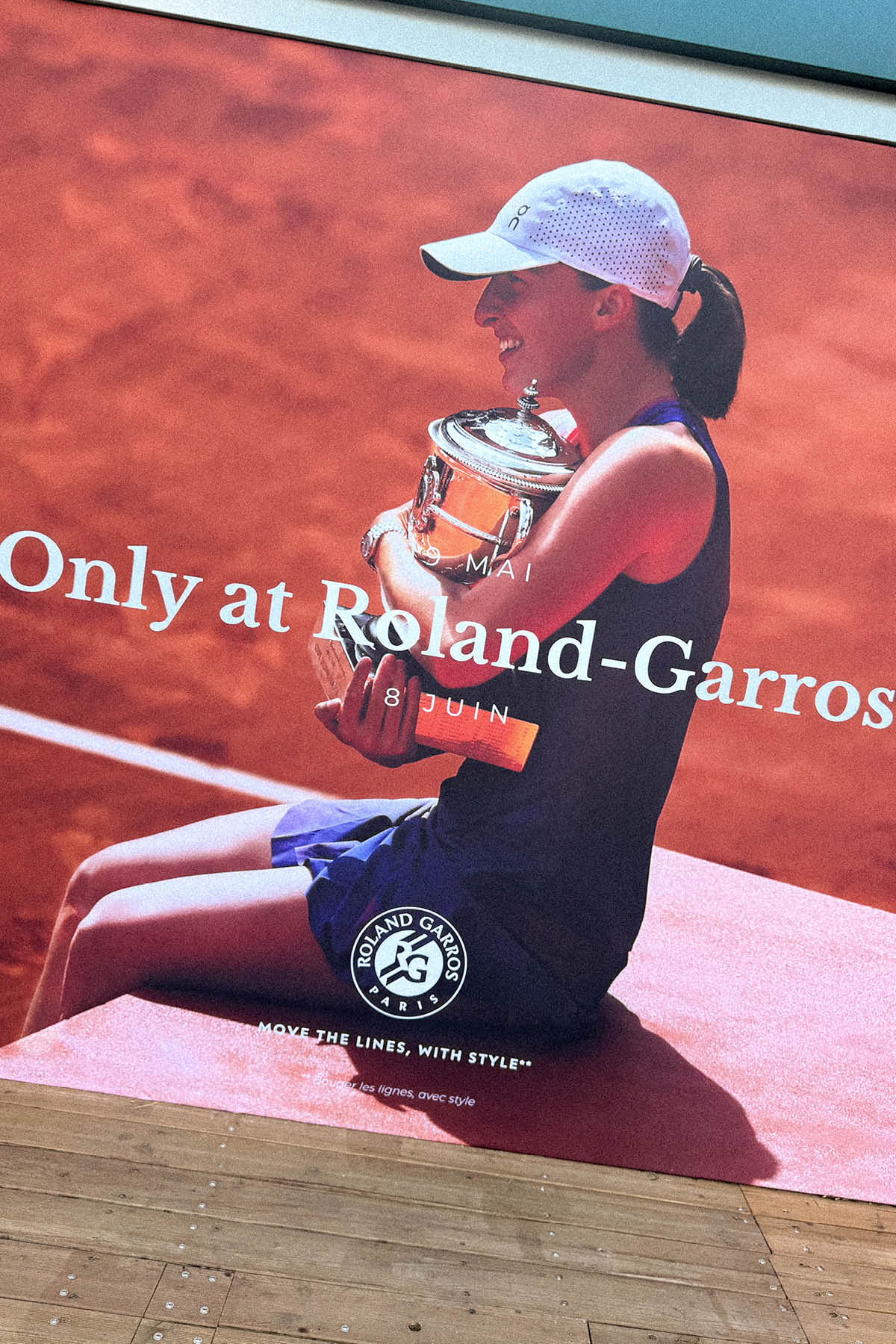

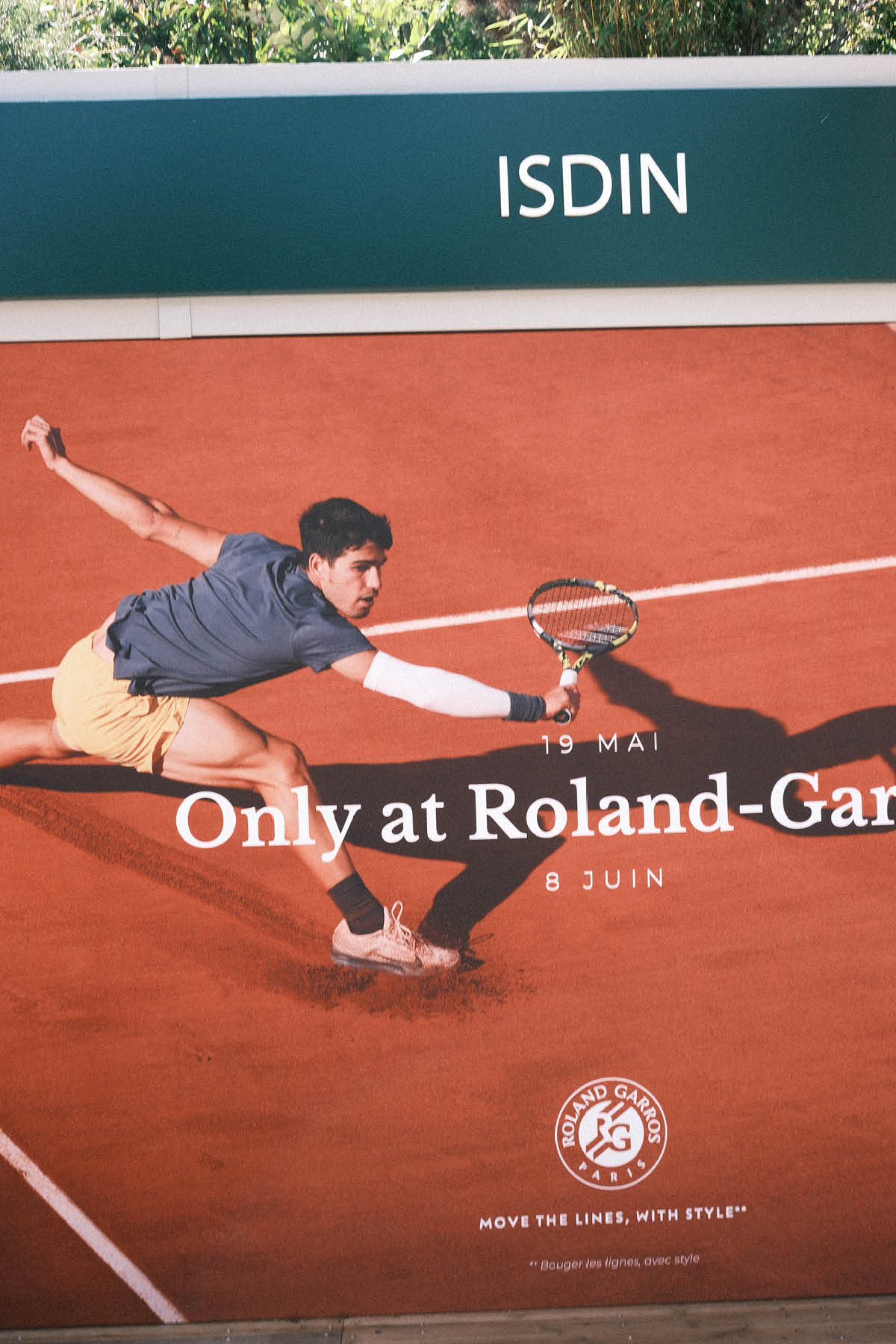

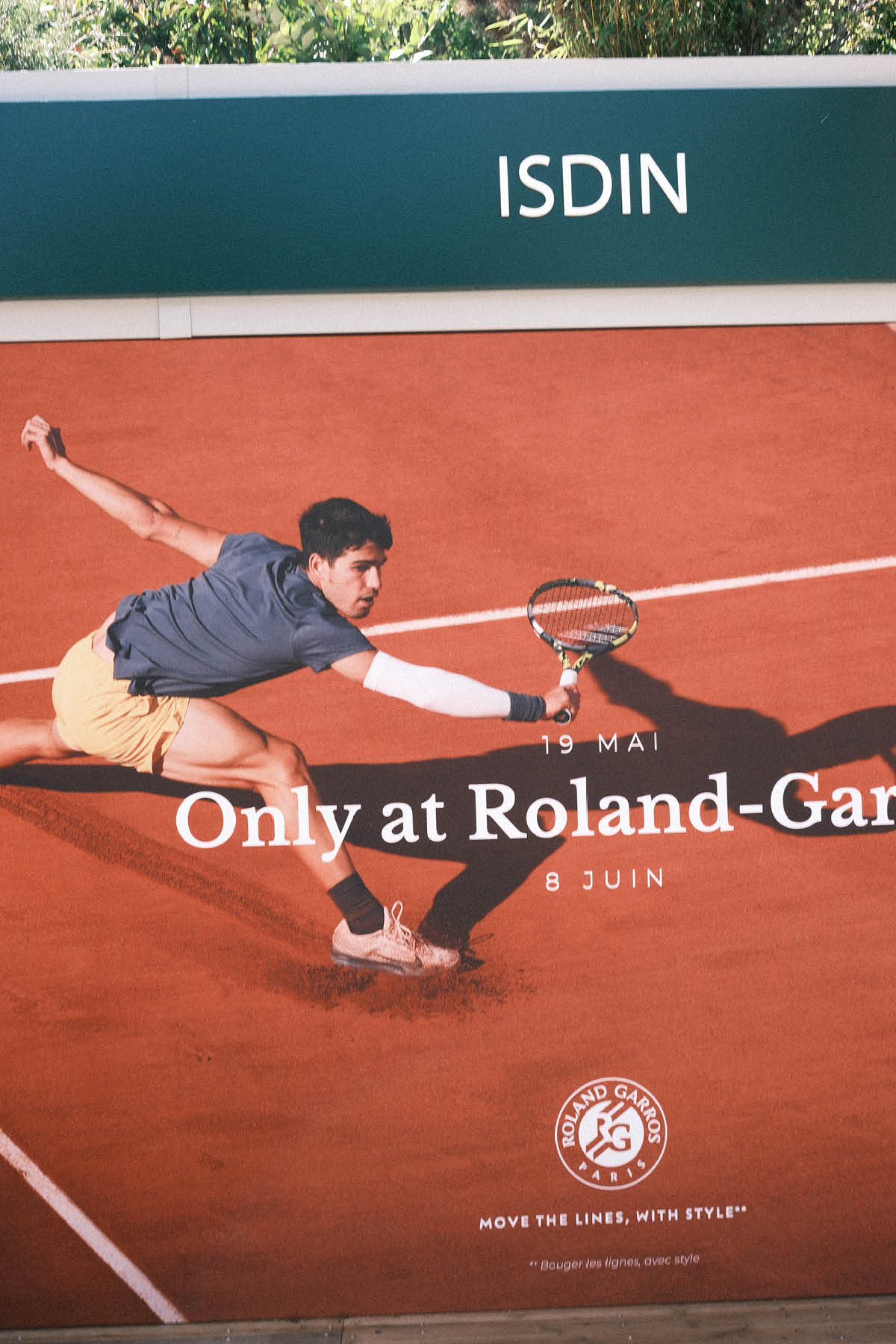

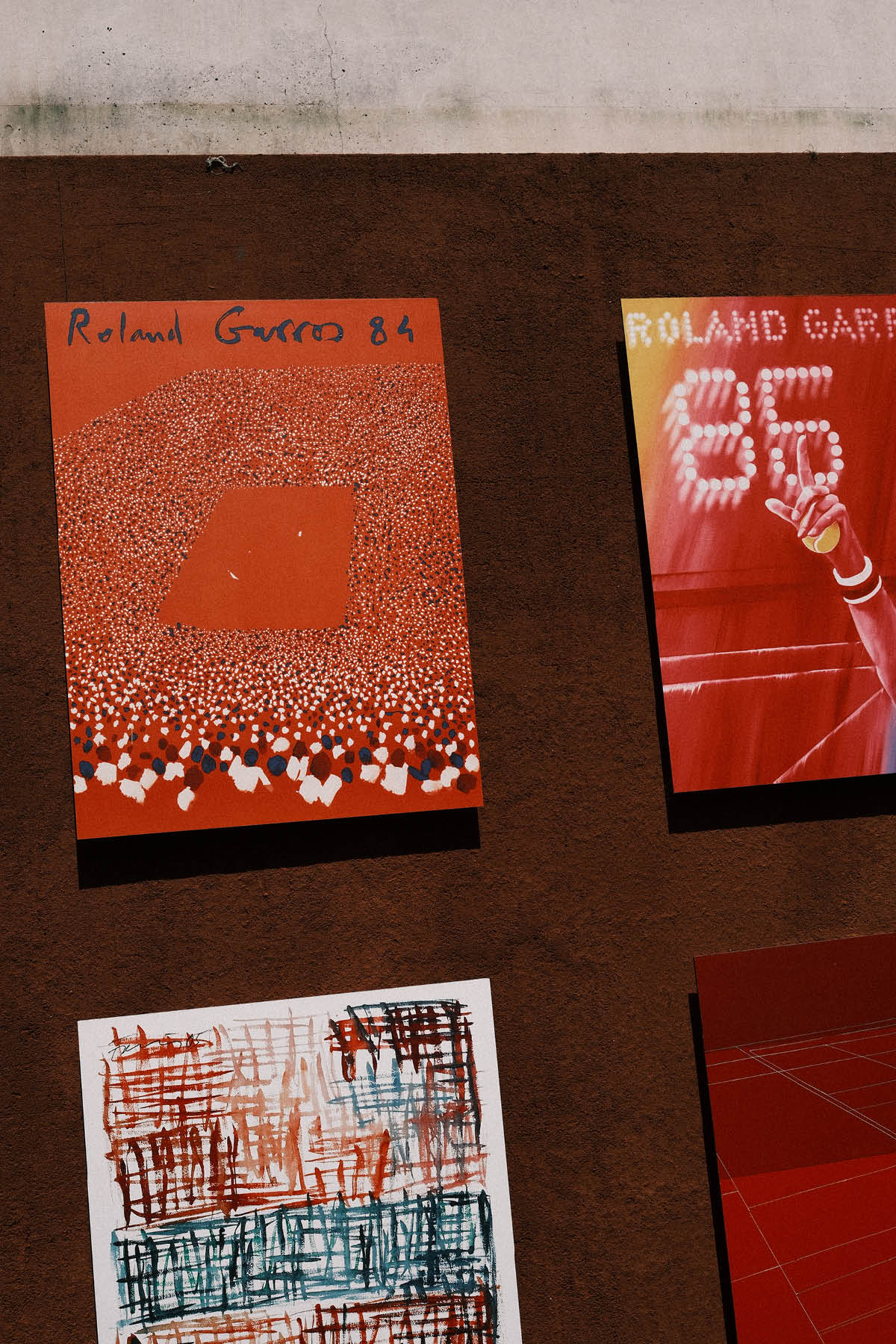

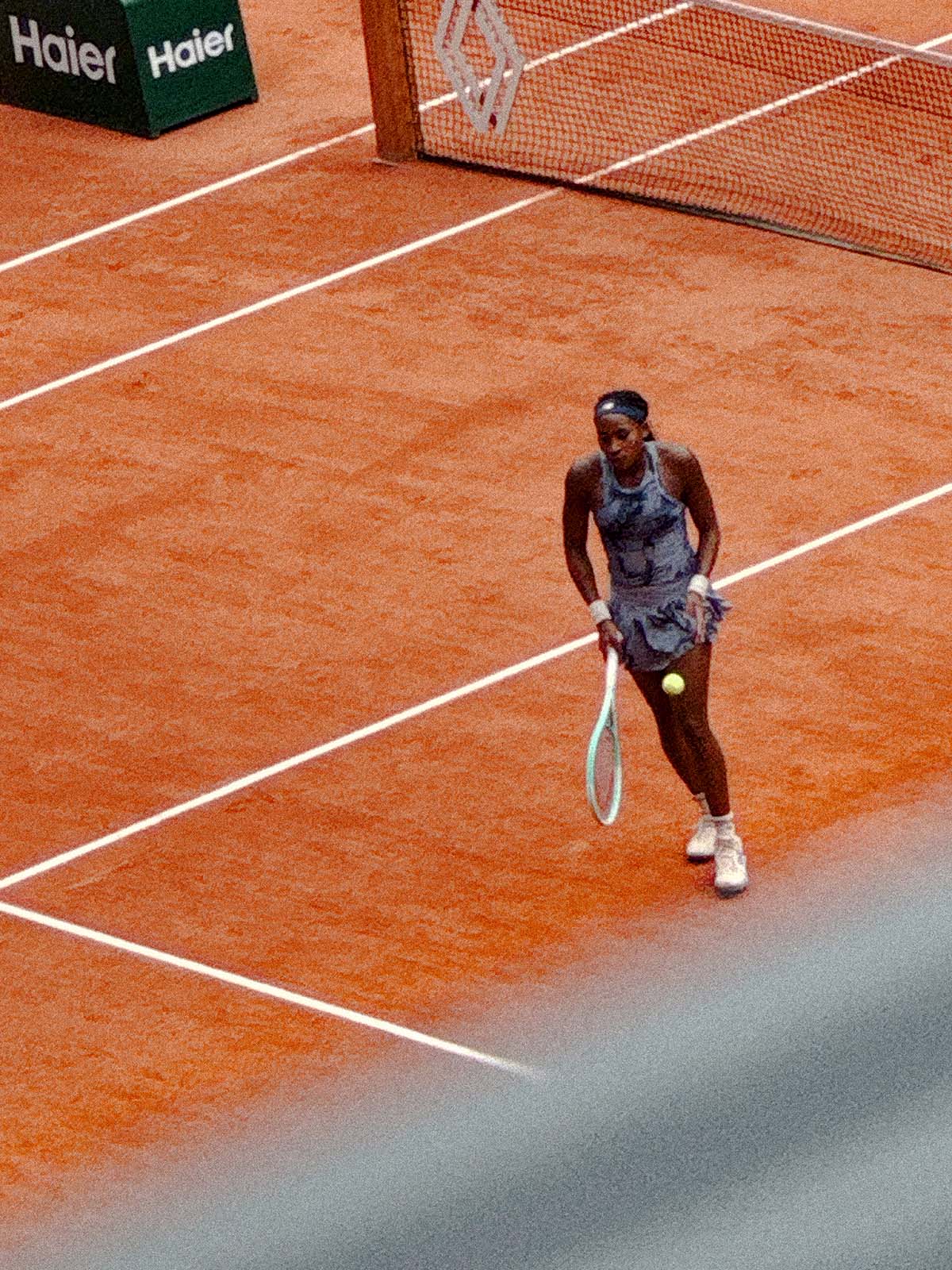

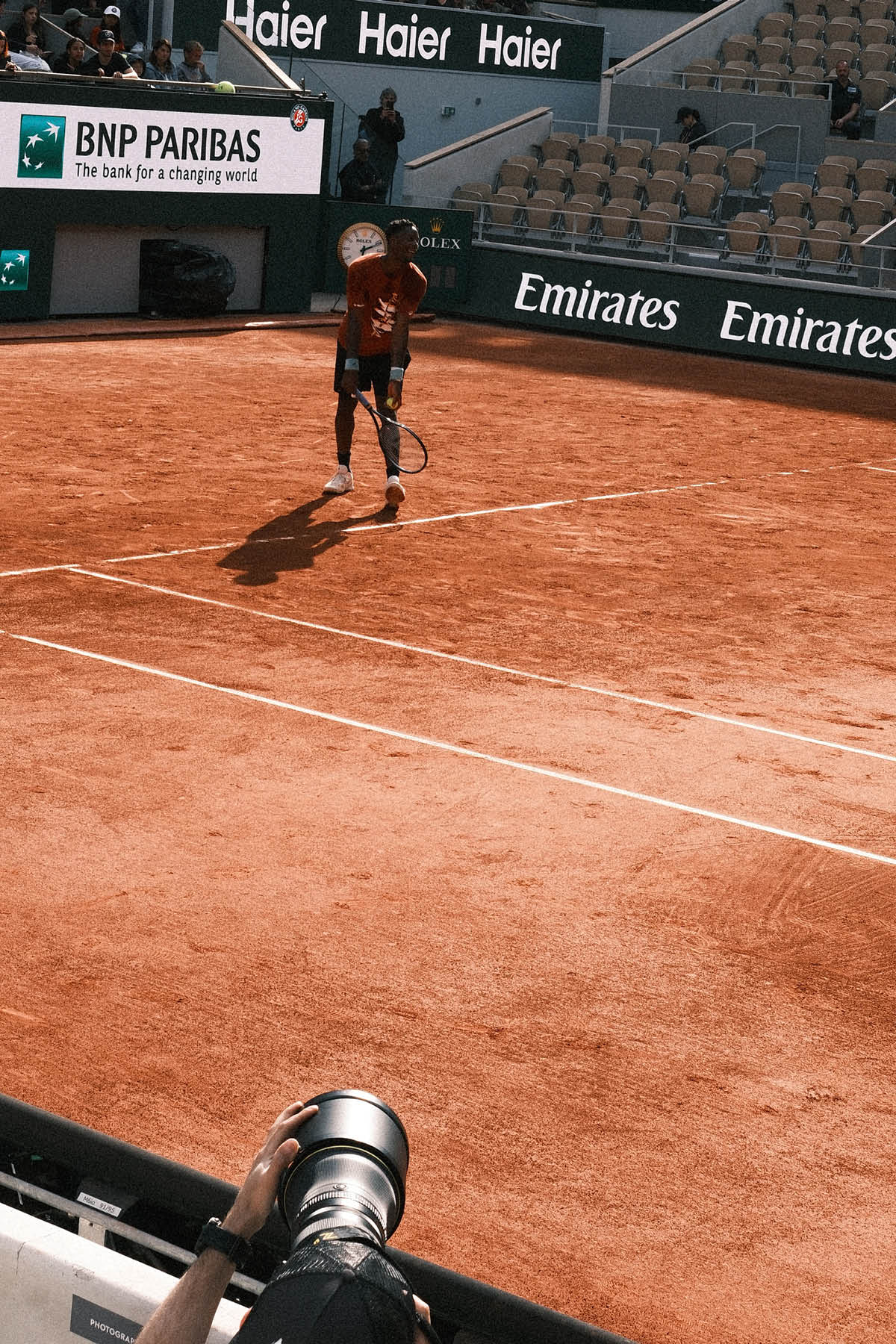

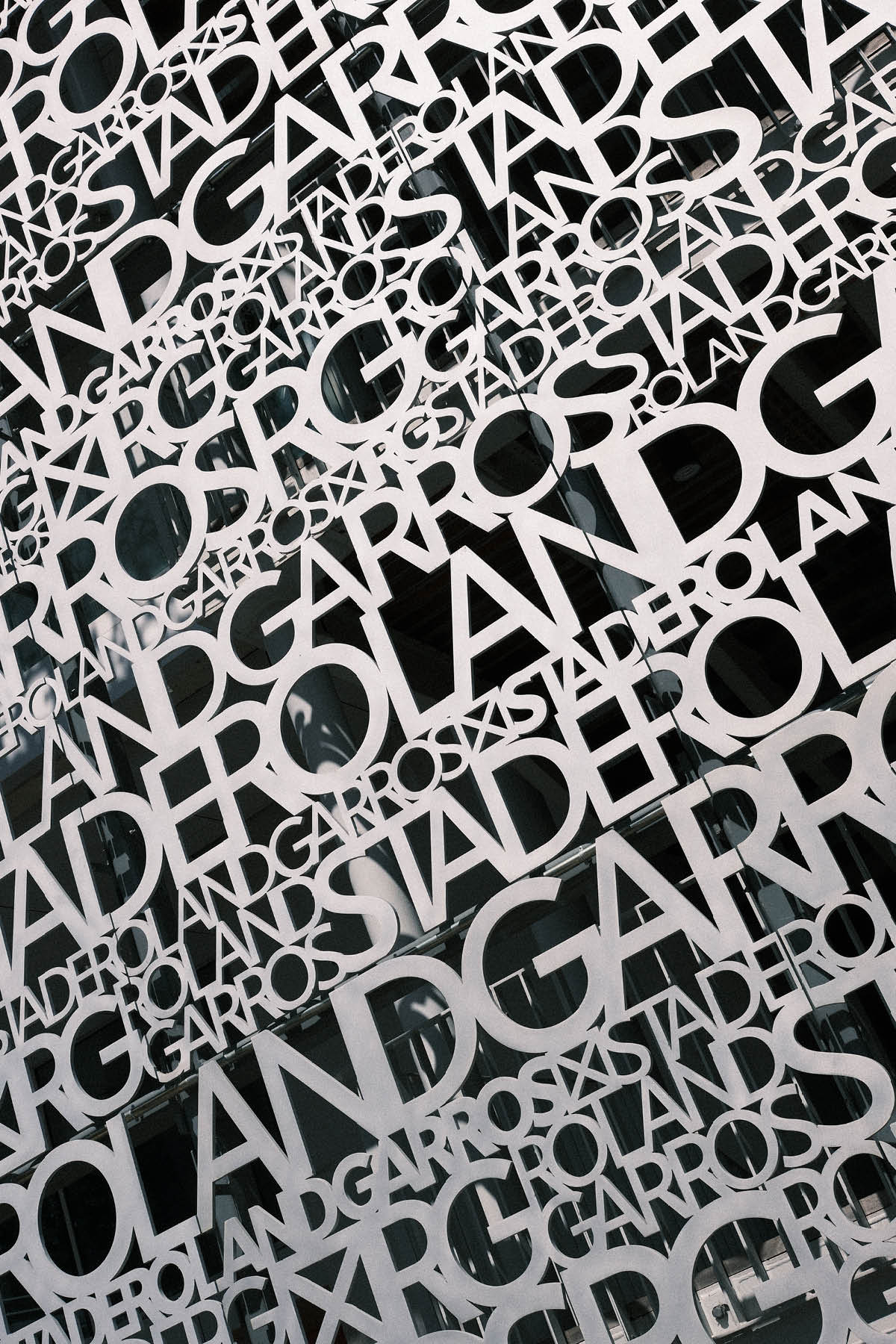

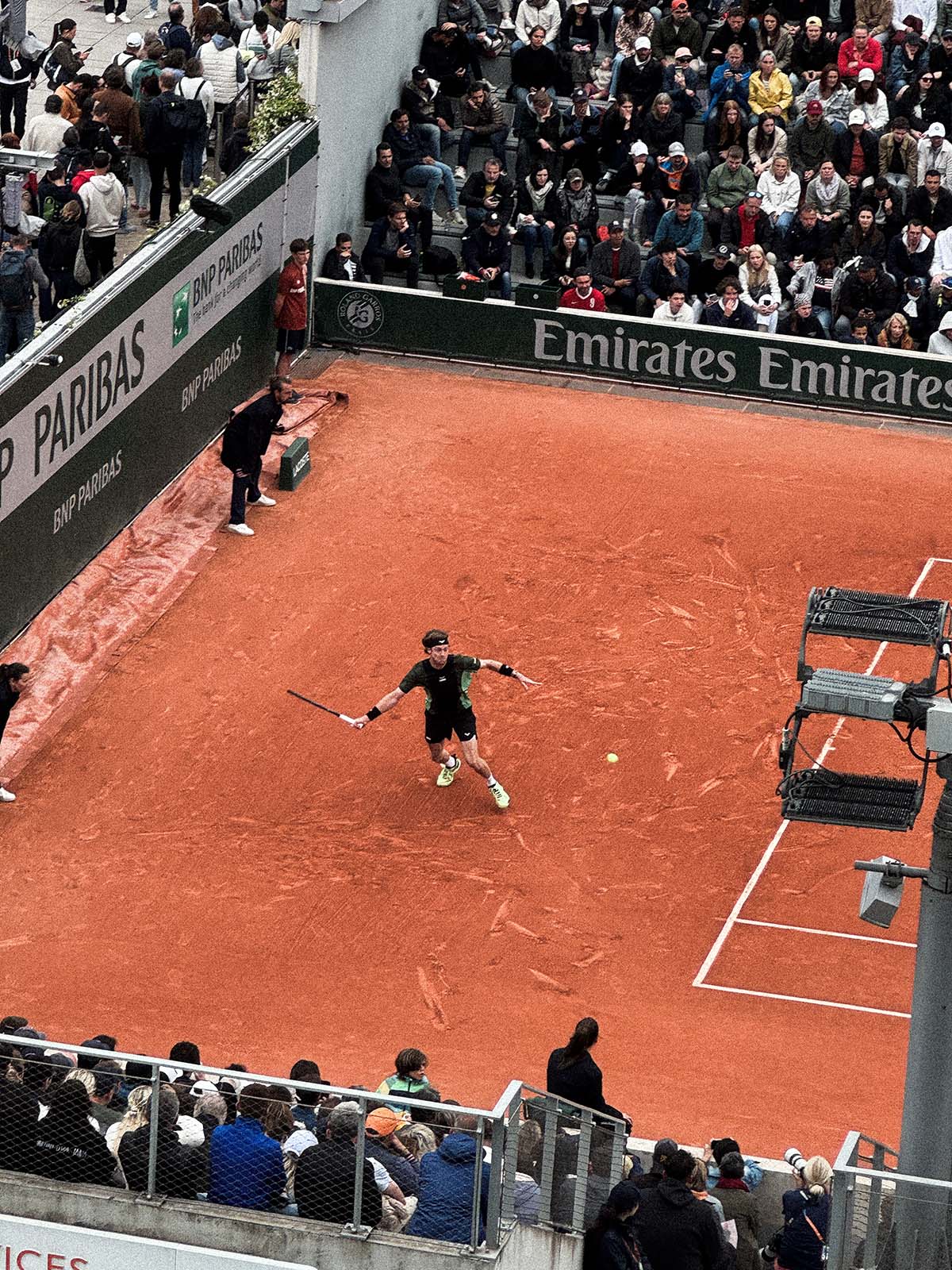

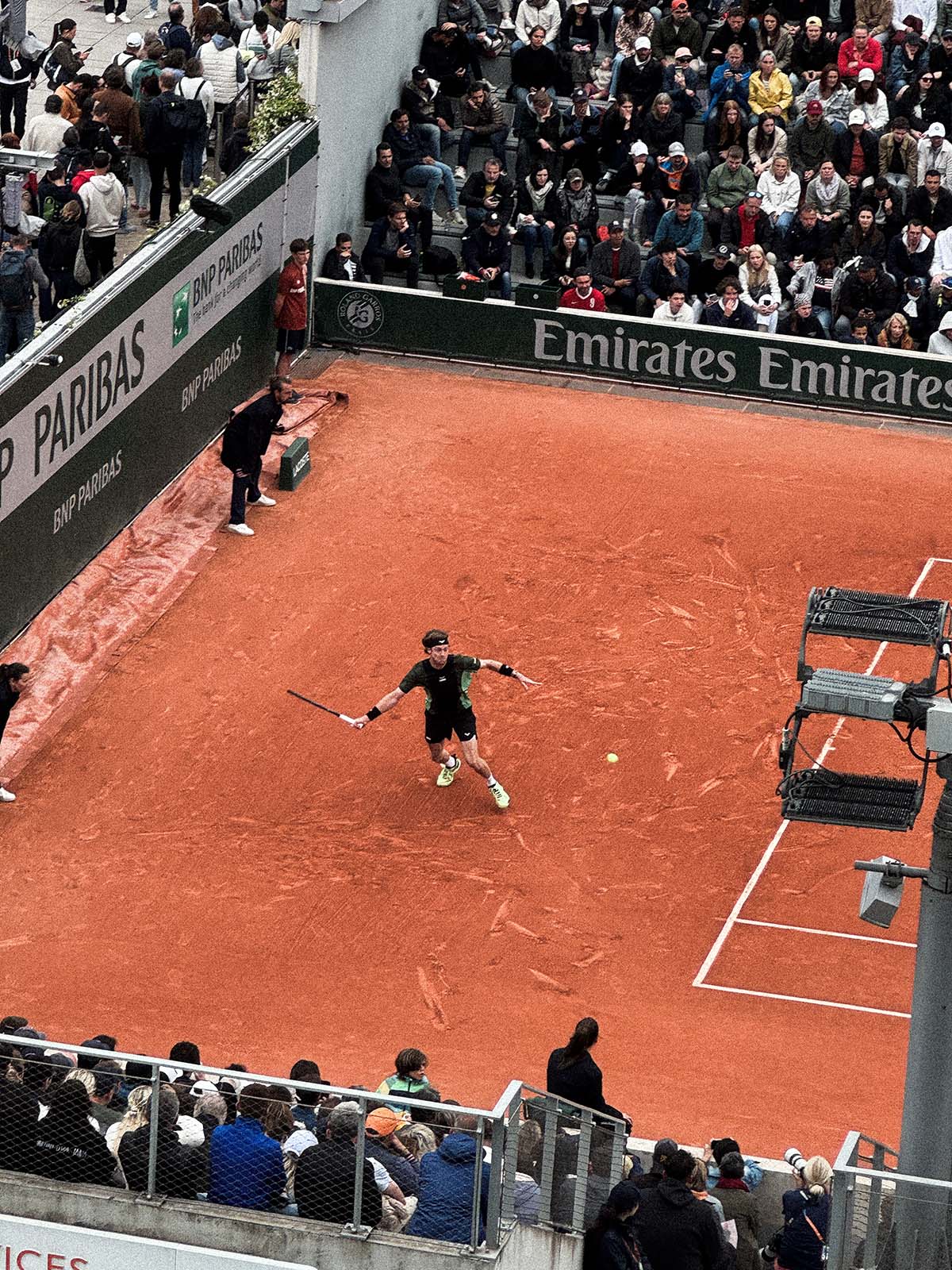

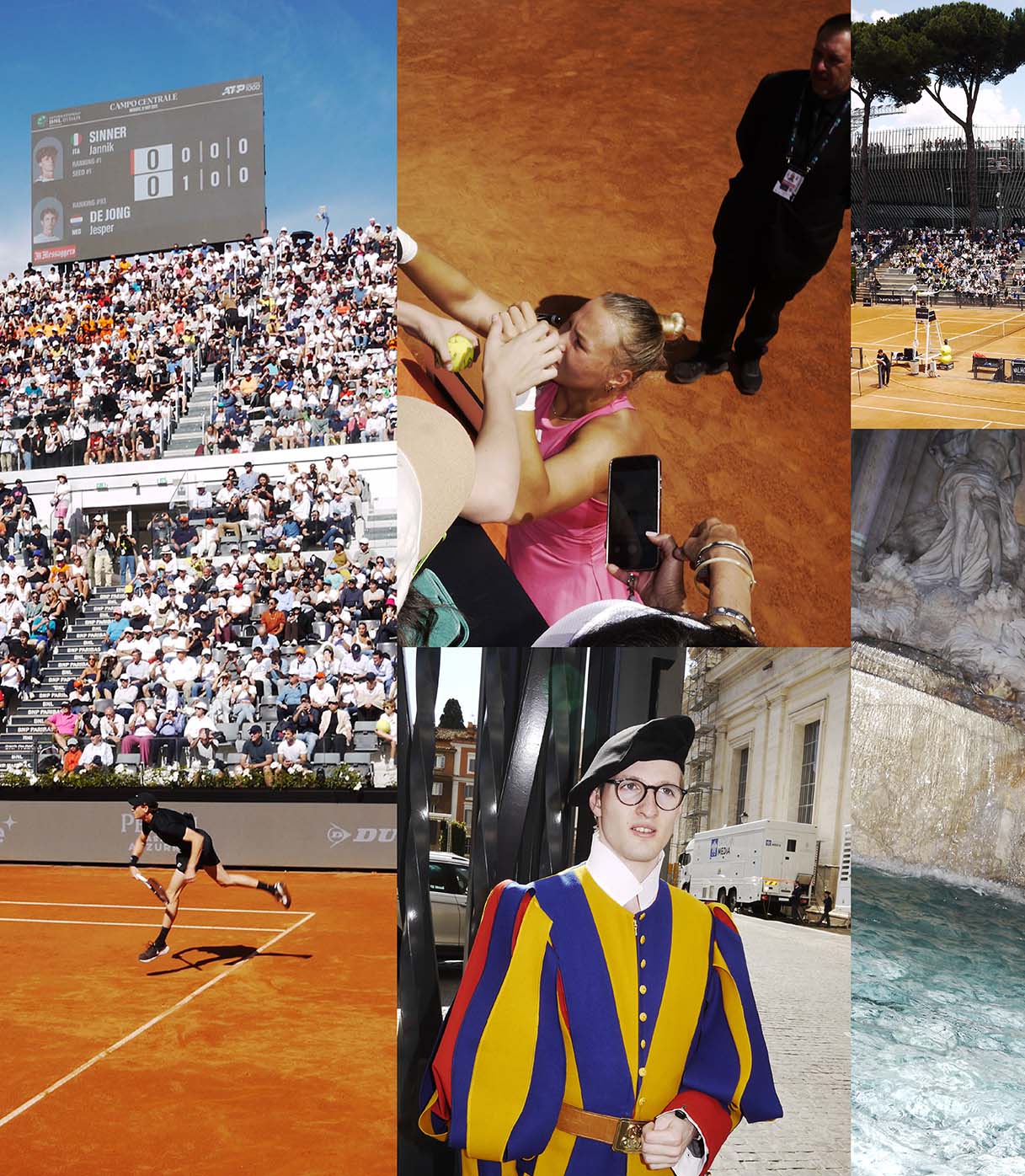

Postcard from Roland-Garros

Postcard from Roland-Garros

Postcard from Roland-Garros

Rewinding the sights and sounds of the

2025 French Open.

Rewinding the sights and sounds from the 2025 French Open.

Photography by David Bartholow

June 5, 2025

SIGN UP — YOU'RE ONLY AS GOOD AS YOUR SECOND SERVE.

The Roland-Garros 2025 Shoe Report

The Roland-Garros 2025

Shoe Report

The

Roland-Garros

2025

Shoe Report

The Fashion Slam brings colorful footwear into play.

The Fashion Slam brings colorful footwear into play.

By Tim Newcomb

May 30, 2025

Let’s coin Roland-Garros the Fashion Slam. That includes the footwear, especially as brands experiment with color anew each spring in Paris.

While the Happy Slam kicks off tennis’ major calendar each January in Australia, often with bold, summer-forward kits, for Roland-Garros, brands typically welcome an array of springtime colors and graphics, and generally roll out fresh takes on on-court tennis fashion. Whether it’s Nike mixing in a bounty of different footwear options for players on the red brick, Wilson offering up a classic colorway for sponsored players, New Balance giving athletes a gray-focused approach, or custom touches throughout the tournament, Roland-Garros showcases a diverse and fashion-forward collection of footwear befitting its Paris address (even if some of the best examples were one-round wonders).

Carlos Alcaraz

Nike Vapor 12

The fully customized Carlos Alcaraz shoes from Nike—cast as a Nike Vapor 12—give the four-time major winner his own colorway within the Nike family. The largely black, white, and light blue sneakers match his kit and include a small red logo on each heel.

Getty

Getty

Andrey Rublev

K-Swiss K-Frame Speed Rublo

K-Swiss hasn’t yet launched the brand-new K-Frame Speed Rublo, designed in conjunction with Andrey Rublev, but the world No. 15 is sporting the shoe that will launch July 1. In Paris, his version is yellow and black.

Images courtesy of K-Swiss

Images courtesy of K-Swiss

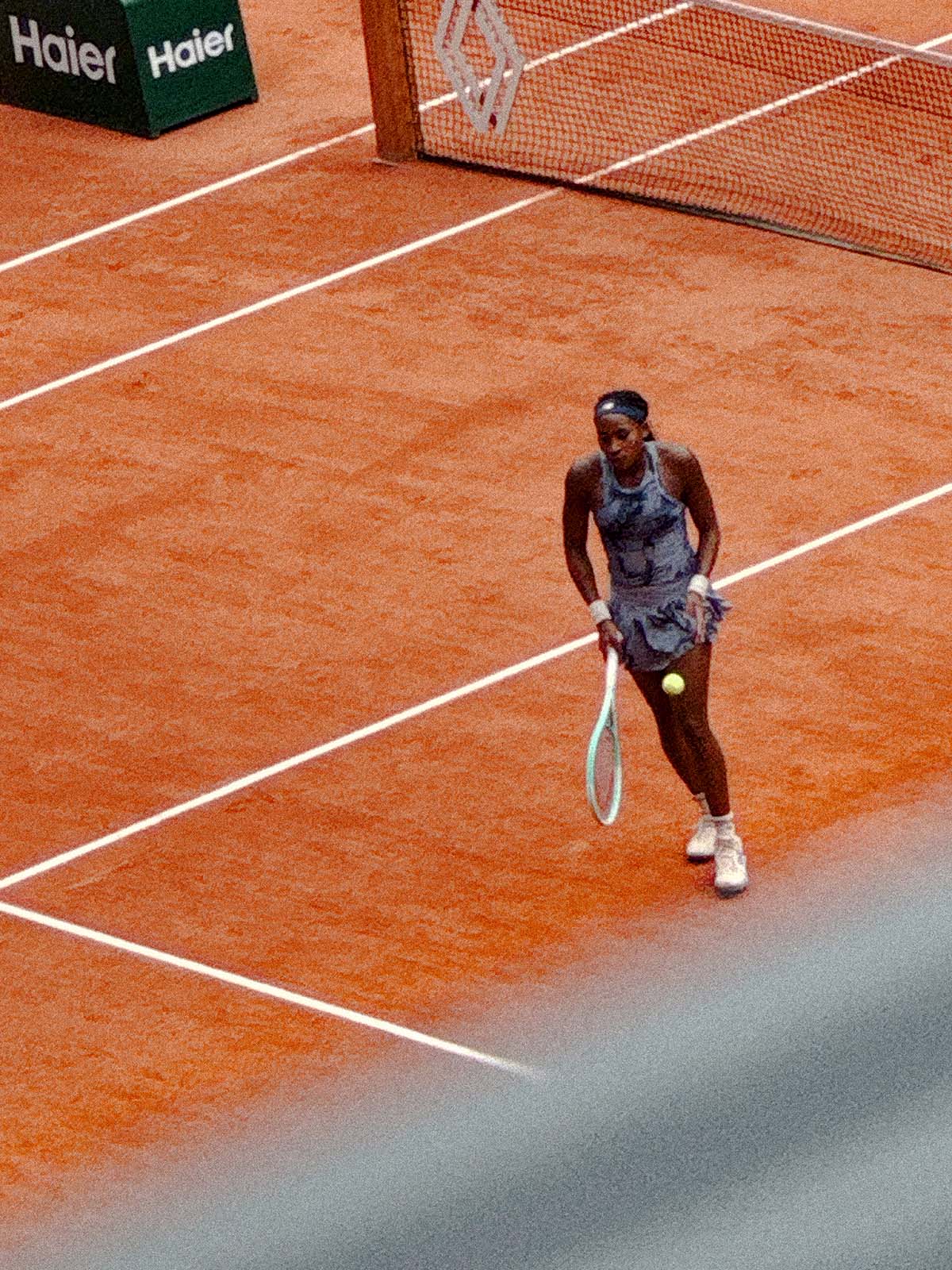

Coco Gauff

New Balance CG2

Each May, New Balance celebrates the brand’s “Grey Days.” Coco Gauff’s signature shoe joined the mix with the Coco CG2 x Roland Garros, where the gray steps back to reveal the “linen” and “dusk shower” light blue. The grayed-out linen color features true gray on the outsole and heel, and the blue-gray dusk shower tone is seen in the midsole and the “N” logo. New Balance says Gauff “wanted a mix of a coastal vibe with a French Parisian style” while opting for a “classic and mature” design.

Image courtesy of New Balance

Image courtesy of New Balance

Novak Djokovic

Asics Court FF3 Novak

There’s a color update for Novak Djokovic and the 2025 clay season. For Roland-Garros, the Asics Court FF 3 Novak goes white and “electric red” while including the Djokovic logo.

Images courtesy of Asics

Images courtesy of Asics

Naomi Osaka

Nike GP Challenge 1

One of the best colorways of the tournament lasted only three sets. Nike and Naomi Osaka continued the pair’s 2025 flower theme for Roland-Garros, offering up a GP Challenge 1 in a “Sakura” design (cherry blossom), full of four different pink shades across the shoe. Paired with white, the pink cherry blossoms matched Osaka’s kit. “Spring is Sakura season,” Osaka wrote on Instagram before the tournament. “The girlies are gonna love this one.”

Images courtesy of Nike

Images courtesy of Nike

Marta Kostyuk

Wilson Intrigue

In another example that didn’t make it out of round 1, Marta Kostyuk’s Wilson Intrigue colorway is fortunately not tied to just her model. The Wilson footwear line, inspired by the colors seen “on an afternoon in Paris during clay season,” features the Intrigue and Rush models with a white base and classic striping of red, orange, yellow, green, and blue. Possibly the best touch, though, is the scrumptious gum sole.

Images courtesy of Wilson

Images courtesy of Wilson

Yonex players are mostly in the Eclipsion 5 clay version, with “ink blue” for men and “dark navy” for women. In a fun touch from the Japanese brand, sponsored players typically have their name and country’s flag included on the upper.

The mainline Nike options for Roland-Garros feature two key colorways. One is, according to the brand, dusty cactus, pale ivory, metallic silver, and dark team red, while the other is deep night, pale ivory, metallic silver, and light crimson, including World No. 1 Jannik Sinner finally switching to a Nike Zoom GP Challenge 1. Both options come with a silver-accented, Paris-inspired tongue logo and a metallic silver lace tag.

adidas has five different models hitting the red brick of Roland-Garros, with the Barricade, Defiant Speed 2, Ubersonic 5, Cybersonic, and Avacourt 2. Throughout it all, adidas embraced neon yellow, although black is also an option for the athletes.

Speaking of neon yellow, On outfitted its players—Joao Fonseca, Ben Shelton and Iga Swiatek—in a “lime” and “limelight” colorway of the Roger Pro 2 Clay.

Sneaker free agent Frances Tiafoe continues to wear K-Swiss, and this tournament his K-Swiss Ultrashot 4s match his blue Lululemon kit.

Reilly Opelka has an all-pink Fila Axilus 3 Energized, breaking away from the white-based colorway most Fila-sponsored players are wearing.

Daniil Medvedev wore a dark blue and purple player-edition model of his Lacoste AG-LT shoes during his first-round loss that featured his name on the tongue.

Babolat players are opting between orange and black footwear options in Paris.

While Leylah Fernandez lasted only one round this year, she is continuing to wear her father’s unreleased Aesem Athletica shoe.

Follow Tim Newcomb’s tennis gear coverage on Instagram at Felt Alley Tennis.

SIGN UP — YOU'RE ONLY AS GOOD AS YOUR SECOND SERVE.

A Weekend in Rome with ellesse

Rome, If You

Want To

Rome, If You Want To

A weekend in the Eternal City with ellesse, where the iconic Italian brand turned heads with a comprehensive reset.

A weekend in the Eternal City with ellesse, where the iconic Italian brand turned heads with a comprehensive reset.

By TSS

May 23, 2025

The tennis moment wouldn’t be happening

SIGN UP — YOU'RE ONLY AS GOOD AS YOUR SECOND SERVE.

Postcard from the Italian Open

Postcard from the Italian Open

Postcard from the Italian Open

Legendary German photographic duo Lotterman & Fuentes take on Roma.

Legendary German photographic duo Lotterman & Fuentes take on Roma.

Photography by Lottermann & Fuentes

May 16, 2025

SIGN UP — YOU'RE ONLY AS GOOD AS YOUR SECOND SERVE.

Will She? Won't She?

Will She? Won't She?

Will She? Won't She?

Naomi Osaka is finding solace on clay this year. Now what?

Naomi Osaka is finding solace on clay this year. Now what?

By Carole Bouchard

May 14, 2025

Naomi Osaka takes flight on the red clay of Rome this week. // Getty

Naomi Osaka takes flight on the red clay of Rome this week. // Getty

Will she or won’t she? What? Come back. But she’s already back. No, but you know, at the top: Will she come back at the top? The only thing people seem to want to witness from Naomi Osaka since last year is a return to her previous level, competing for Grand Slam titles. So the less she finds a way to do it, the more dramatic the “will she, won’t she” storyline becomes. Yet, what if clay was Her Moment? Imagine!

Surprisingly, this clay season has come to Naomi Osaka’s rescue as she clinched eight wins in a row, from Saint-Malo’s final to Rome’s fourth round (a loss she called “atrocious”), on a surface she doesn’t like, doesn’t have good memories of, and never spent enough time on. Her best record on clay yet. She was sweating through three-set wins against players she surely felt she should still trounce in straight sets like she did back in the day. Who would have predicted that after a first-round loss in Madrid? Yes, she could be a dark horse at Roland-Garros, no doubt, and also, yes, she could suffer an early exit. The uncertainty cloud around her is less thick, but it has still not fully cleared.

Osaka’s case reminds us how tennis is fascinated by former champions returning to the sport after going through it. People love a fairy tale of winning against all odds, the “rising from the ashes” storyline. We were all glued to Michael Jordan’s journey in The Last Dance, and we’ve been spoiled throughout the years in tennis with it happening repeatedly, from Andre Agassi to Serena Williams, Kim Clijsters, Thomas Muster, Rafael Nadal, Roger Federer, or Maria Sharapova post–shoulder surgery. Some forgot it’s not a given. Ask Andy Murray!

Still, nothing like a champion turning mortal before becoming a superhero again to renew fans’ interest. It’s even stronger for Naomi Osaka as you can feel the not-so-subtle “Please, Naomi, come back” vibe. The fans, the sponsors, the media, and the tour all want to see more of one of the most bankable players in tennis. It’s not just for the feels: The tennis business needs her. And so Osaka’s only option seems to be this incredible comeback following pregnancy and injuries to the top of the mountain again.

And she’s trying so very hard. Osaka tried so much that she hurt her back during the Asian swing last year. And this year so much so that she got an abdominal injury that not only cost her a title in Auckland but also a deep run at the Australian Open. She was hitting the ball like the former world No. 1 she is and moving the best I had seen her move in ages. But she broke, and it killed all her momentum. It also kills what Osaka needs the most but struggles to keep: her confidence. She told me in Madrid she loved how Patrick Mouratoglou was helping her build her confidence again, as she tends to be “too insecure.” That’s what puzzles people about Naomi Osaka: how she can be an extremely ambitious woman building an empire on and off the court, yet someone who doubts so much.

Naomi Osaka had planned the start of 2025 to be her moment, yet it ended in an emotional blow. That’s why, to me, her clay season so far has been admirable. Think about it. Naomi Osaka is now asked to rise from her ashes through the tennis stretch she dislikes the most: clay season to grass season. Awful timing, right? Maybe not. Last year, she played a blockbuster at Roland-Garros against Iga Swiatek in the second round, so couldn’t she build on that again a year later?

When I saw her in Madrid, she said that instead of going straight on clay after Miami, she had a whole block of preparation for clay at the Mouratoglou Academy in the South of France. I paused. Naomi Osaka prepared for clay season?! Color me impressed. But she still lost in the first round in Spain against Lucia Bronzetti, whom she barely beat last year in the first round in Paris. Then what? Rome and Roland-Garros? Did she go through all that for two events?

Osaka was livid, ranting on Threads, “Trust the process, but the process isn’t trusting me wtf. I wouldn’t wish what goes on in my brain to my worst enemy.” And so she did what champions do and also triggered her fairy-tale-waiting-for-happy-ending storyline again: Cinderella forgot about the castle, the prince, and the cute glass shoes and got down a few notches. Naomi Osaka needed matches and some wins, so she put her ego aside and discovered the beautiful city of Saint-Malo in France and its WTA 125 world. Andre Agassi going through the Challengers to build his return type of vibe. The amount of “omg wow, Osaka back to WTA 125 level, this is so brave” takes I’ve read… Everything for a good narrative and drama!

Nobody can say Naomi Osaka isn’t trying, or doubt she wants to get back to the top. Why? She was down 4–1 in the second round against Diane Parry in the third set of a WTA 125 in a city she probably didn’t even know existed before landing in it. She has all the millions she can dream of in the bank, a successful production company, a daughter she doesn’t see as much as she’d love to because of tennis, and some serious emotional troubles tied to tennis. She could have been on a private jet to the beach real quick to forget about it all. But no, she fought her way back into that match and ended up winning the tournament.

Naomi Osaka won her first title on clay, her first title in four years, in 2025 in Saint-Malo, a WTA 125. Plot twist! That’s what her tennis and confidence needed. And so the narrative machine got back on track again: “Will she now?” The thing is that the word “nearly” has become a big part of Naomi Osaka’s return story. She nearly got Swiatek at Roland-Garros last year. She nearly won the title in Auckland. She was near a deep run at the Australian Open. Naomi Osaka is still so close, and yet somehow so far. Close to her best level? Absolutely. To dominating the sport again? Not sure about that. But the main thing is that she wants to try. That’s what this clay season is showing us: Naomi Osaka is still up for the fight.

The Hopper

—CLAY Tennis on Beatriz Haddad Maia’s US Open run.

—Giri on Iga Swiatek’s loss to Jess Pegula.

—Jon Wertheim’s mailbag is full this week.

—Sara Errani and Andrea Vavasori have won the US Open mixed doubles.

—Tim Newcomb on Taylor Fritz and Asics.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

It Started in Italy

It Started in Italy

It Started in Italy

Diadora USA head Bryan Poerner talks about bringing the brand’s made-in-Italy program to the tennis court, with its all-new B. Elite Star.

Diadora USA head Bryan Poerner talks about bringing the brand’s made-in-Italy program to the tennis court, with its all-new B. Elite Star.

By Tim Newcomb

May 13, 2025

Images courtesy of Diadora

Images courtesy of Diadora

Diadora boasts a rich Italian heritage, one full of nostalgia, history, and made-in-Italy designs, going back to the company’s birth in 1948. Not one to live in the past, though, Diadora has brought its made-in-Italy program to the tennis court, crafting the all-new B. Elite Star at the brand’s Italy headquarters and manufacturing facility in Caerano di San Marco. The new on-court offering joins made-in-Italy models for off court, such as the B. Elite and B.560.

The Second Serve’s Tim Newcomb chatted with Bryan Poerner, president and CEO of Diadora USA, on why the made-in-Italy program is important to the family-owned brand, and what makes it unique in the world of tennis.

Why is the made-in-Italy program important to Diadora?

We’ve always done it in soccer and reintroduced it in running three or four years ago. This is our first tennis introduction. The thing that is interesting about what we do is this is not a commercialization strategy of “Let’s sell the most stuff.” Yes, we are competitive and want to sell, but this is more about “How do we actually build the best things?” There are lots of ways to approach this, scientifically and with labs, which we have, but we started thinking that if we want to have this process to come up with the best court shoe—sketching it out, building the compound, stitching it, testing it, adjusting it, testing it again—if we can do that in our home, where designers, the lab, and factory are within 100 meters of each other, there is something there you can’t replace.

It is not a commercial option to have all our shoes built this way, but it is a celebration of how we develop our shoes. It is a celebration of Italian craft, but also what the Diadora design process is.

What is the made-in-Italy B. Elite Star?

The B. Elite Star is a new shoe we developed, and it is the first made-in-Italy technical tennis shoe that we have done in 30 or 40 years. It pays homage to the Bjorn Borg B. Elite, but only in design reference. We paid homage to it but wanted to push the boundaries and made sure it was a badass technical, playable shoe. The B. Elite is one of the most celebrated shoes in our history, so we started from that design language and were figuring out how to modernize. It was really fun.

What makes the B. Elite Star unique?

When people see it, they say, “Oh, it is beautiful.” Because we took this design language from the B. Elite, it is one of the gnarliest all-court shoes that has ever been developed. We just said we are going to build the best hard-court shoe possible, and it wasn’t about reaching a price point. The [midsole] compound we use, the production value of the raw materials, it is the anima—Italian for “soul,” so it has a double entendre—of the shoe but also what makes the shoe special. There is a responsiveness around that. It is 30 percent more responsive with 30 percent more bounce back from impact to return than the next competitive set of shoes. And even with that performance, we got it down to a little more than 12 ounces with all the best materials and a good level of durability. I’m really proud of it. We don’t just make stuff; we try to make the best thing. Made-in-Italy is our best representation.

Will we see the made-in-Italy program expand in performance tennis?

I would love it to, but I don’t know. With the tariff situation, with capacity, with demand, we will see. The demand for our made-in-Italy running product keeps growing, but then it comes down to the actual capacity to build shoes. Do we invest in more factories around Caerano? This is not a mass-production thing. We want all these details to be felt. There are a lot of factors involved, but I will say that the way we have developed shoes for the last 50 years will stay the same.

What are the lifestyle models of the made-in-Italy tennis program we’ve seen?

These are replicas of Bjorn Borg, Boris Becker, Jennifer Capriati, anyone who played in our shoes. Select models of their shoes we still manufacture like we did 30 to 40 years ago. We do small runs for boutiques all around the world. These are one-for-one replicas and are nods to the past.

How does Diadora’s history help it in the tennis space?

The reason I came here in the first place is it is the most amazing brand. It is a family company. Take all the [feats by athletes] away and it is a family company obsessed with providing high-level products to athletes. There is tremendous value in that. The people at this company obsess over the athletes, and how to serve them better is part of every decision we make. How do you give someone not only an advantage in tennis, but an advantage when playing on grass, or on wet grass, or playing doubles on grass? We don’t think about profit and loss when building footwear for Nicole [Melichar-Martinez], a doubles player of ours; we think about how to deliver the best shoe on this day.

Why is tennis important to Diadora?

It is core to what we do. We are not an every-sport brand. We do calcio [Italian for soccer], tennis, and running. Those are the sports we do, and we want to do them super, super well, so we are going to be very focused on driving the best product to market. That is a different approach than a commercialization strategy where you find the opportunities to sell the most stuff. Sometimes they are very commercial, and sometimes they are not.

How is that strategy different?

If you think about it, it is similar to Ferrari. They are thinking about building a race car. That is not a commercialization strategy. They are not building a compact $35,000 car that can maybe get you there, but it isn’t going to be the fastest, hold you the best, or corner the best. We are more concerned with this [high-performance] market, and we can live in this world. It is a different approach than most of our competitors.