Desert Dropshot

Desert Dropshot

Desert Dropshot

Club Leftist Tennis’ Jackson Frons checks in with a scene report from Indian Wells.

Club Leftist Tennis’ Jackson Frons checks in with a scene report from Indian Wells.

By Jackson Frons // Club Leftist Tennis

March 14, 2025

Donna Vekic battles Madison Keys in tennis paradise. // David Bartholow

Donna Vekic battles Madison Keys in tennis paradise. // David Bartholow

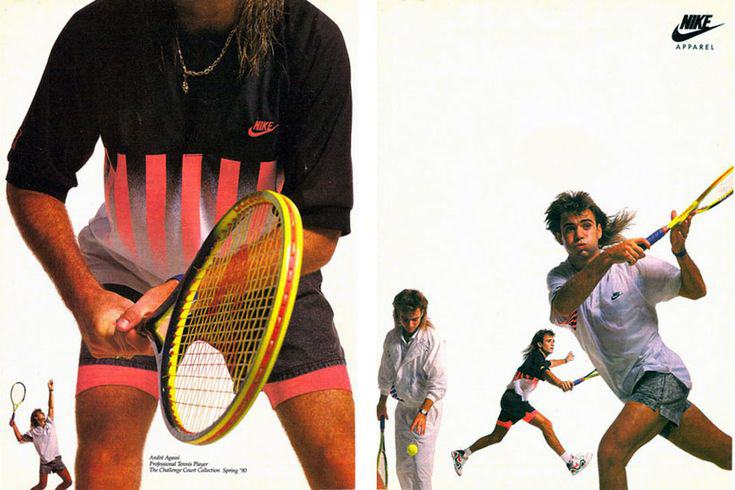

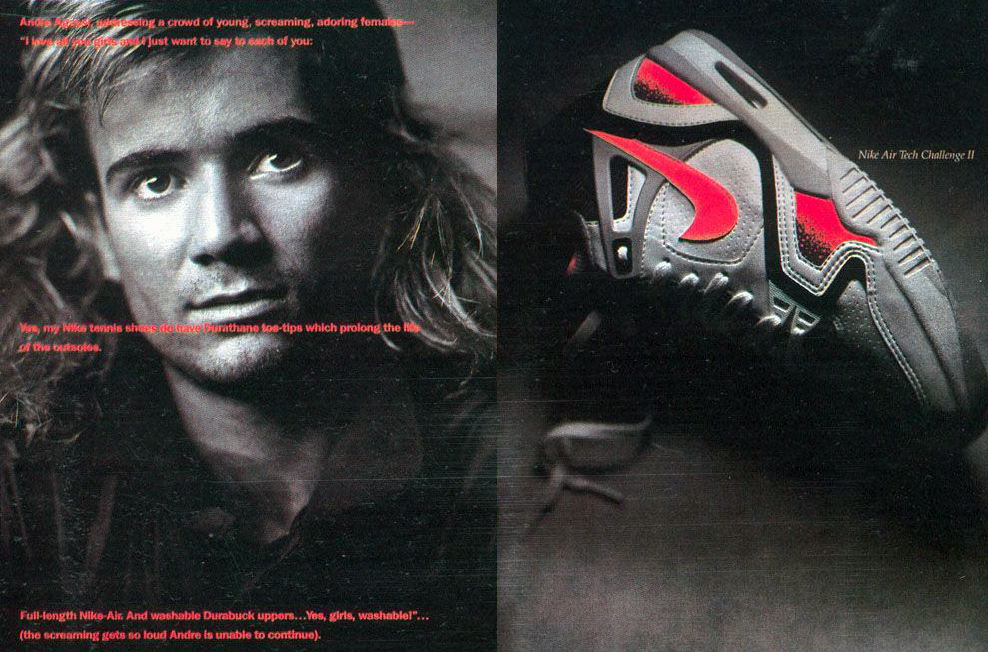

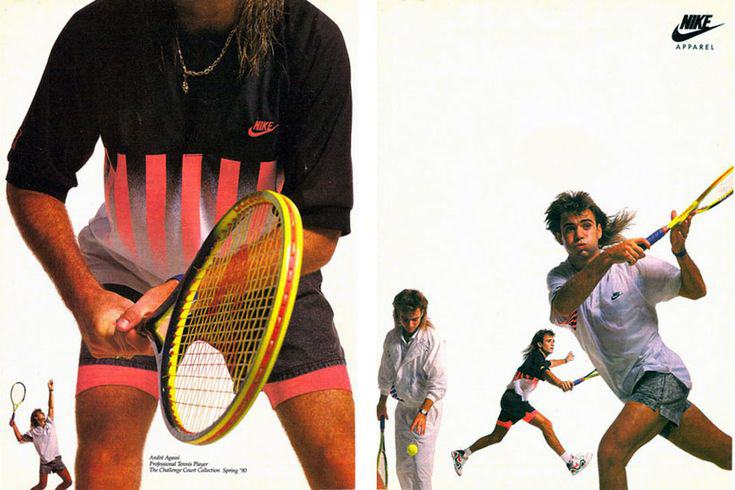

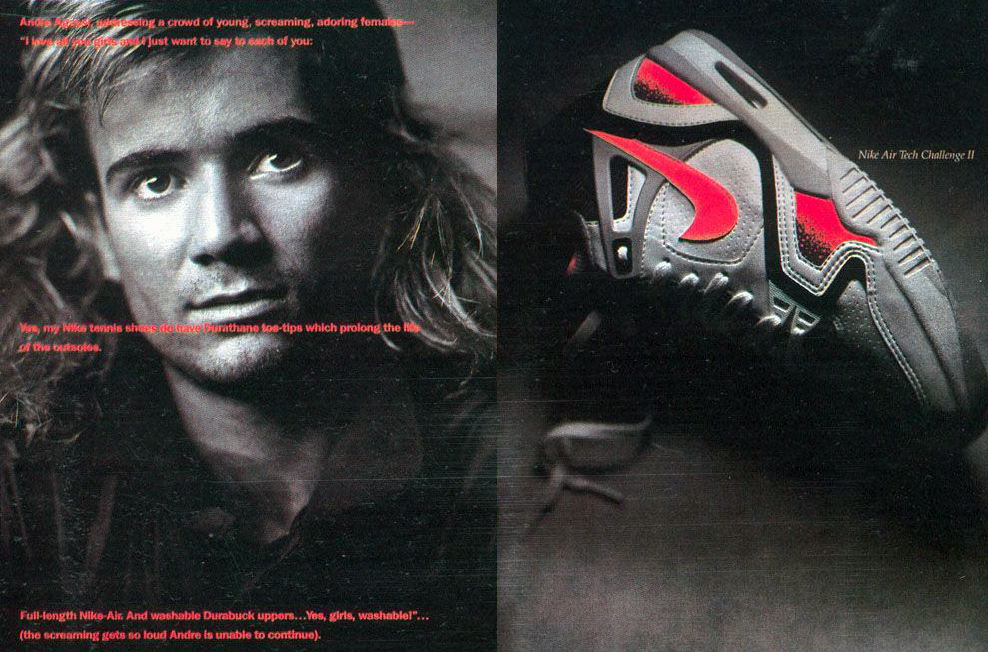

On Monday afternoon at the BNP Paribas Open, as I roasted in the sun seated behind the Stadium 3 baseline, a group of boomer guys in my section spent an entire set trying to say “Botic van de Zandschulp” correctly. They never got close. Later, one of them speculated that an all-girl crew of ball kids was “DEI.”

Compared to them, I felt like a tennis genius. After Botic went down to Francisco Cerundolo, Hubert Hurkacz came out and opened his fourth-round match against Alex de Minaur by serving a bevy of unreturnable 140 mph bombs that painted lines. I thought to myself, “This guy will never get broken. He might even win the tournament.” However, over the next 90 minutes, Alex de Minaur bolted from corner to corner, absorbing blow after blow, until Hubie’s forehand disintegrated and de Minaur waltzed to the next round with a 6–4, 6–0 win. So much for my expertise.

So went my three days in the desert at Indian Wells. Just when I thought I understood what was going on, that I’d captured the vibe, my understanding got disturbed. Much like Stefanos Tsitsipas’ new racquet—a Babolat Pure Aero painted all black and stenciled as if it were a Wilson—things were not always as they seemed.

My initial impression of the crowds this year was that they were sparse, tepid, and didn’t know very much about tennis. Monday night, as Donna Vekic and Emma Navarro played a tightly contested first set on Stadium 2, the first-come-first-serve upper deck was packed (although quiet), while the box seats barely held enough people to form a USTA 3.5 team. Things filled up more later for the show put on by Gael Monfils and Grigor Dimitrov, but I’d hardly describe the environment as electric despite the often show-stopping action on court.

It wasn’t until the following evening, on a day elongated by rare desert rain, that people lost their shit. Due to the many delays, which, contrary to podcaster Craig Shapiro’s Instagram story advice to “pound it out at Porta Via,” I mostly spent wandering around, gazing up at the drizzle, Stadium 1 ushers stopped checking tickets and let fans from the nosebleeds fill the lower levels for the second half of the three-set clash between Arthur Fils and Marcos Giron, as well as the subsequent headliner: Daniil Medvedev vs. Tommy Paul.

Maybe it was that Americans were playing or the thrill of newly acquired incredible seats, but it seemed like dozens of people in the stadium suddenly believed they’d been hired on to the coaching teams of Paul and/or Giron (with a few thrown in for Fils, too). One of them, seated not far from me, continued bellowing increasingly desperate tactical advice after almost every point (“Big targets, Tommy!”) as the American No. 2 lost eight consecutive games to close out his exit from the tournament.

Stef questions his new hardware. // David Bartholow

Stef questions his new hardware. // David Bartholow

During my time in Tennis Paradise, I was also struck by the sanitized apoliticality of Indian Wells. While tennis generally reads as less American than our domestic major sports, whose pregame rituals usually include some type of Troop Salute, even the U.S. Open indulges a bit in nationalist impulses.

The Tennis Garden, by contrast, embraced a blank, timeless internationalism. Landscape aside, I felt like I wasn’t in California or America or any discernibly regional place. Instead, this was a nationless, godless land in which only commerce existed.

None of the many things you could buy—fashion, food, etc.—were particularly tethered to “the now.” Aside from a few fits in the Fila tent and a Detroit Pizza vendor, the Hip Tennis wave that seems inescapable just a couple hours away in L.A. was basically nowhere to be found here. It was all very pan-2000s pseudo-luxury, perhaps best exemplified by: a Nobu outpost, copious ads for the Motorola Razr, and (paradoxically considering the nominal apoliticality of it all) the Saudi PIF tent.

I decided to hit up the PIF tent because, unlike Nobu (and most things at Indian Wells), it was free. After being given a pair of complimentary pins (that I’m sorry to admit go incredibly hard), the kind staff told me how the PIF was sponsoring a ticket giveaway for the next day. All I needed to do was scan a QR code and log some play time on the digital game stations scattered around the tent. All of the games had a line, however, and I couldn’t figure out why the PIF was mandating them for the giveaway. They already harvested all the personal data they could possibly want from the sign-up. In the end, I declined.

Like many things at Indian Wells, the Saudi influence thought to blend in. It’s all good. All regular. All normal business, no different from La Roche-Posay or the Veroni charcuterie.

I had much more interest in the things that stuck out. The fans who really didn’t know ball. The aggressively bad graphic T-shirts promoting BNP Paribas. And, after all, the players.

I find watching live tennis magnifies weapons and weaknesses. The asymmetries of a player’s games that so often get blurred by the distance of a TV broadcast pop more when you’re in the building. The way Daniil Medvedev swallows space with his gangly movement. How Ben Shelton’s serve and forehand explode off the court, and that his focus dramatically ebbs and flows in a match. It’s even clearer how Madison Keys’ boundless power can dwarf even a fellow big hitter like Vekic. Or how Coco Gauff, despite her guile and grit, tries to avoid her erratic forehand on big points.

It’s stuff like that that makes seeing tennis live in any environment—be it a 1000-level event in Tennis Paradise or the qualifying rounds of Futures at a ramshackle club—an engrossing and gripping experience. No matter how much or little you know, there’s always a new nuance to spot, a new thing about the match to figure out.

The tennis, however, may not have been the most visually striking thing at Indian Wells. That honor, in my book, goes to the Dropshot, the neon green signature drink sold around the grounds and sponsored by the Station 29 Casino. Unlike its rival in New York, the much-hyped (but ultimately mid) Honey Deuce, the Dropshot looks in no way fit for human consumption.

When I finally worked up the courage to order one on Wednesday, my first question wasn’t “How much does this thing cost?” but “What is in this…” It turned out it was basically all pineapple, of various forms, and a shot of tequila. The green hue was pure food coloring.

As for the taste, I actually didn’t mind sipping my Dropshot from my seat on Stadium 1, the weather once again bright and sunny, the fragrant culinary exhaust wafting up from the concession stands toward the pale desert sky. That is, until I reached the grainy “pineapple salsa” at the bottom of the cup, which may have been the worst thing I’ve tasted in 2025. By this time, down on the court, wild card Belinda Bencic, looking to continue her Cinderella run, was serving up 5–4 in the third against Coco Gauff. Behind me, a member of a group of guys who loved saying “boom” in the middle of points remarked to no one in particular, “I’m pretty sure Coco needs to win this game. If she loses it, the match might end.”

Meddy's been in good spirits. // David Bartholow

Meddy's been in good spirits. // David Bartholow

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

New Balance Debuts ‘Coco Delray’ Tennis Sneaker

New Balance Debuts ‘Coco Delray’ Tennis Sneaker

By Tim Newcomb

March 12, 2025

Images courtesy of New Balance

Images courtesy of New Balance

Not every fan of Coco Gauff is ready to pull off her signature high-performance New Balance Coco CG tennis sneaker. New Balance knows that. So, the Boston-based brand created the “Coco Delray,” a more inclusive addition to the New Balance world of Coco, offering a low-top model without all the bells and whistles found on the Coco CG line.

The new shoe, named after Gauff’s Delray Beach hometown and the courts she grew up playing on, is still court-ready, though, just in a more streamlined version. The carbon fiber shank of the CG gets replaced with TPU, but the outsole is the same and the shoe can hold up to the tennis court, all while being designed to make it more wearable off the court. The low-top upper is meant to fit the needs of more players but is still inspired by heritage basketball, as is the CG2 model.

Josh Wilder, New Balance footwear product manager for tennis, says the Coco Delray has a similar look to the CG and is still ready for tennis but offers “another way to bring more people into the fold” while being able to pull off a lifestyle aesthetic. Upcoming CG colorways will inform future iterations of the Delray. The Delray retails for $110 and releases today.

Follow Tim Newcomb’s tennis gear coverage on Instagram at Felt Alley Tennis.

SIGN UP — YOU'RE ONLY AS GOOD AS YOUR SECOND SERVE.

SIGN UP — YOU'RE ONLY AS GOOD AS YOUR SECOND SERVE.

Self-Portrait at Tennis Paradise

Self-Portrait at Tennis Paradise

Self-Portrait at Tennis Paradise

Indian Wells embodies Southern California escapism.

Indian Wells embodies Southern California escapism.

By Jackson Frons // Club Leftist Tennis

March 7, 2025

Coco Gauff and Elena Rybakina tune up at tennis paradise. // David Bartholow

Coco Gauff and Elena Rybakina tune up at tennis paradise. // David Bartholow

While the U.S. Open might be “the biggest stage in tennis,” New York isn’t exactly Tennis Town, USA. The best juniors and pros rarely (if ever) relocate to train at Billie Jean King, and for us mortals, even getting a court in the city during the winter months requires money, foresight, and/or a gratuitously long train ride. America’s tennis capitals lie elsewhere—in Florida and Southern California.

It’s fitting, then, that the regions host the dueling events that make up the Sunshine Double—the Miami Open and the BNP Paribas Open at the Indian Wells Tennis Garden, aka Tennis Paradise. Without undue offense to the “beautiful” South Florida parking lot, I think Indian Wells, as a venue, captures the strange spirit of Southern California far more completely than its East Coast counterpart evokes the Florida tennis scene.

The first time I went to Indian Wells was in 2008. The tournament, back then, was called the Pacific Life Open, and the Garden was less than a decade old. Ana Ivanovic bested Svetlana Kuznetsova in the women’s final, and Novak Djokovic, fresh off his maiden Australian Open title, took home the men’s crown wearing that hideously iconic Adidas shirt that was smeared with a digital S.

I was 13 then, and there with my friend Eitan and our moms. He and I had met a few years before this via remarkably ’00s Californian circumstances—playing ping-pong on a cruise to Alaska. It was only after arriving back at LAX that our families figured out we all lived in Encino and that Eitan and I were both tennis players. In fact, it turned out we went to private schools on the Mulholland strip that shared a fence. His father, an imposing former tank gunner in the IDF, used to stand on the balcony of their house, gazing down at their private court, bellowing at us in his thick Israeli accent as we hit, “Enough with the fancy shots, Eitan! Heet the ball in the quart!”

Southern California tennis, like Southern California itself, is an incongruous sprawl. There are the state-of-the-art complexes at UCLA and USC. The ritzy old money hangs like the Los Angeles Tennis Club, the Riviera, and Pasadena’s Valley Hunt Club. The private courts, like Eitan’s, that are innumerable in certain parts of town. The public parks and the high school facilities riddled with cracks and raggedy nets. The endless banks of courts in Orange County. Clubs carved into blank suburbia and soundtracked by freeway noise. The kinds of places with accompanying apartment complexes and golf courses with grass hydrated to an iridescent green. While Florida might be home to humid Har-Tru clay, what unites Southern California is that it’s hard-court country.

I grew up playing tennis here. Although I lived in the San Fernando Valley, the packed multi-weekend tournaments took me from the stadium courts at the Barnes Center in San Diego to the rickety municipal courts in Santa Barbara and nearly everywhere in between. I’ve played in Fullerton, Seal Beach, Whittier, Long Beach, Irvine, Northridge, Calabasas, Anaheim, Carson, Lakewood, the Jack Kramer Club, Coto de Caza, the desert, and too many other places to count.

Every tournament site stunk of sunscreen, and the “come on”s echoed to the parking lots. Heavy topspin was the de facto game, and it often seemed you could punch someone in the face without getting a code violation. The draws were diverse in level, race, and socioeconomic class. The matches were chaotic. The academy kids from Weil and Advantage came from all over the world. All, or at least many, of us harbored hopes (or delusions) that one day, if everything broke right, we might end up playing in front of the crowds in Tennis Paradise one day.

But what is Tennis Paradise? In the Southern Californian imagination, it’s a blustery, stoic tennis garden known (historically at least) for its comically slow courts that appears almost like a mirage. There’s great viewing. Minimal chain-link. Ideal weather (well, at least this time of year). Luxe digs. A Nobu outpost for the tournament. Those mountains. In a region where so many places look like other places, there’s nowhere else like Indian Wells. It’s easy to forget, walking under the shadow of Stadium 1, out amongst the outer courts, great tennis everywhere, that just beyond the parking lot lies a bland, dry landscape smoothed of history and full of blocks where the houses look similar and nearly every store is in a strip mall.

To play one’s best tennis, I’ve found, it behooves you to forget about anything nonessential. Dwelling on the macro issues—stuff like breakups, professional stresses, fires, droughts, or the rising tides of fascism—doesn’t really help you hit your forehand better or stay calm or play one point at a time. To be a truly great tennis player, I’ve often speculated, might require forgetting for a while that anything outside of tennis exists.

It’s possible that escapism is intrinsic to the Southern Californian spirit. This would be the time to insert some bullshit about Hollywood or Disneyland or the monotony of freeway driving. How this is a new country with a short memory, stuffed with recycled ideas. What I can say for certain is that for me, for better and worse, Indian Wells stands as a monument to not acknowledging tennis is ephemeral and ultimately not that big of a deal.

Tennis Paradise isn’t real life. It’s an elongation of that euphoric moment we all get sometimes watching or playing a match when your mind can hold only one thought at a time. When you cock your head to the ball and, for a single moment, the shot is everything.

A tennis oasis. // David Bartholow

A tennis oasis. // David Bartholow

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Nike’s Vapor 12 Hypersmash Basketball x Tennis Mash-up Is Here

Nike’s Vapor 12 Hypersmash Basketball x Tennis Mash-up Is Here

By Tim Newcomb

March 6, 2025

Images courtesy of Nike

Images courtesy of Nike

Nike didn’t waste time in giving the new Vapor 12 a distinct throwback theme, releasing the Vapor 12 Hypersmash ahead of Indian Wells. The shoe is a play on the Hyperdunk basketball shoe from 2008. Nike took the Vapor 12 technology and gave it a colorway to celebrate the “shared respect between hoopers and hard-court stars.” The design takes the popular 2008 Hyperdunk basketball colorway—even re-creating the key Flywire look on the upper with a haptic print on the Vapor 12—and tosses it atop the latest shoe from Nike’s Vapor line. Past Vapor X basketball inspirations include the 2019 Vapor X x Kyrie 5 design based on a signature basketball shoe from Kyrie Irving that was worn on court by Nick Kyrgios and the famed Vapor 9 x Jordan 3 mash-up worn by Roger Federer at the U.S. Open in 2017 (he had previously worn a similar design in 2014).

Follow Tim Newcomb’s tennis gear coverage on Instagram at Felt Alley Tennis.

SIGN UP — YOU'RE ONLY AS GOOD AS YOUR SECOND SERVE.

SIGN UP — YOU'RE ONLY AS GOOD AS YOUR SECOND SERVE.

Fast Learner

Fast Learner

Fast Learner

Learner Tien goes to the head of the class.

Learner Tien goes to the head of the class.

By Giri Nathan

February 28, 2025

Learner Tien in Acapulco. // Getty

Learner Tien in Acapulco. // Getty

Since he first picked up tennis as a toddler, at every age level, Learner Tien has pretty much always been one of the best tennis players in America. That didn’t mean, however, he spent all those years hell-bent on becoming a professional tennis player. Learner’s first coach was his dad, Khuong, who later remembered that his son’s attitude toward a pro career was always one of detached curiosity rather than obsessive commitment. As he put it in a 2023 Tennis Channel segment:

“His famous line was, ‘Well, I’ll just see how far I could go.’ Do you want to be a pro? ‘Yeah, I’m gonna see how far I can go.’ Learner, do you even like tennis? ‘Yeah, I’m gonna see how that’s gonna go.’”

Learner took his time going pro; he even played a bit of college tennis at USC. Once he did make the leap, however, he flew right up the pro rankings. Watching him now, at age 19, already with two wins over top-five players, I am left wondering if that cool, curious attitude is the healthiest possible way to approach a life in sports. Tien never looks frazzled out there on the court, and he wins a lot, with a game beyond his years.

In 2024, a season spent mostly in Challenger and Futures events, Tien racked up 63 wins, including a 28-match win streak from May to July. By the end of the year he had qualified for the Next Gen Finals, where he lost to fellow wunderkind Joao Fonseca in the championship. Fonseca, with all his firepower, fits the more common mold of a prodigy whose unteachable physical talent is discernible after watching three forehands. But Tien played a technically astute game of angles and foot speed. It was something like seeing veteran guile downloaded into a kid’s body. At the end of that tournament, as usual, I was looking forward to keeping tabs on these players who would, in time, break out at the highest level.

But fast-forward just a few weeks and both of those kids were already upsetting top 10 players at the Australian Open. Tien beat world No. 5 Daniil Medvedev in a five-setter that lasted four hours, 49 minutes. It was something of a mirror match. Medvedev was confronted by a much younger player who could match his irritating shot selection and tolerance for brutally long rallies—and, true to mirrors, Tien was a lefty. Whenever Medvedev hit one of his weird off-speed shots, Tien would hit one right back. These two are needlers and meddlers, winning more with precision and patience than with overwhelming power. It’s impressive for a player to have mastered a tricky style like that by age 19, just a few matches into his first season at the ATP level; it took Medvedev until age 23 to fully discover his own game.

I’m not sure I’ve ever heard the word “smart” as often on a tennis broadcast as I did while watching Tien thrive as a qualifier in Acapulco this week—perhaps dozens of times in the span of a two-set match. This initially gave me some pause; was this torrent of “smart” a product of his game (fair), his name (funny), or a stereotype (less funny)? But from what I already knew of his game, and what he revealed over the course of his fourth-round match against Sascha Zverev on Wednesday, it was clear that Tien really did make the right call over and over, and his success on a tennis court was just as attributable to his savvy decision-making as his fast feet. (Maybe it’s just that other players should also be called smart more often.) Tien poked and prodded at Zverev’s problem forehand, played some killer defense, and beat a moody Zverev, who walked off the court and directly into a car.

Afterward Tien was asked if he was enjoying the courts in Acapulco. It sounded as if he was holding back his honest assessment out of politeness; in all likelihood, the molasses-slow court speed is not ideal for a guy who can struggle to muster enough pace to finish the point. That very thing caught up with him in Thursday’s quarterfinal match against Tomas Machac, who overpowered him in straight sets. But what a week it was for Tien, who won four matches and might have been the bright spot of a tournament otherwise defined by mass gastrointestinal distress. And what a year it’s been for him, too. It’s only February of his first full season on the ATP Tour and he’s already beaten two of the best players in the world. The kid who was ranked outside the top 400 this time last year will wind up in the top 70 next week. He’s still so new to tour life that he hasn’t even solidified his schedule for the clay season, as he told Bounces this week, but he at least knows his next stop. After all his success on slow hard courts this week, he’ll soon have plenty more to chew on at Indian Wells. He and Fonseca were both granted wild cards for the main draw there; Tien’s ranking is so high now, he qualified for the main draw on his own merit, freeing up the wild card for someone else. He’s already just another pro.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

All That Love

All That Love

All That Love

Jamaican tennis pioneer Richard Russell

always did things big.

Jamaican tennis pioneer Richard Russell always did things big.

By Ben Rothenberg

February 27, 2025

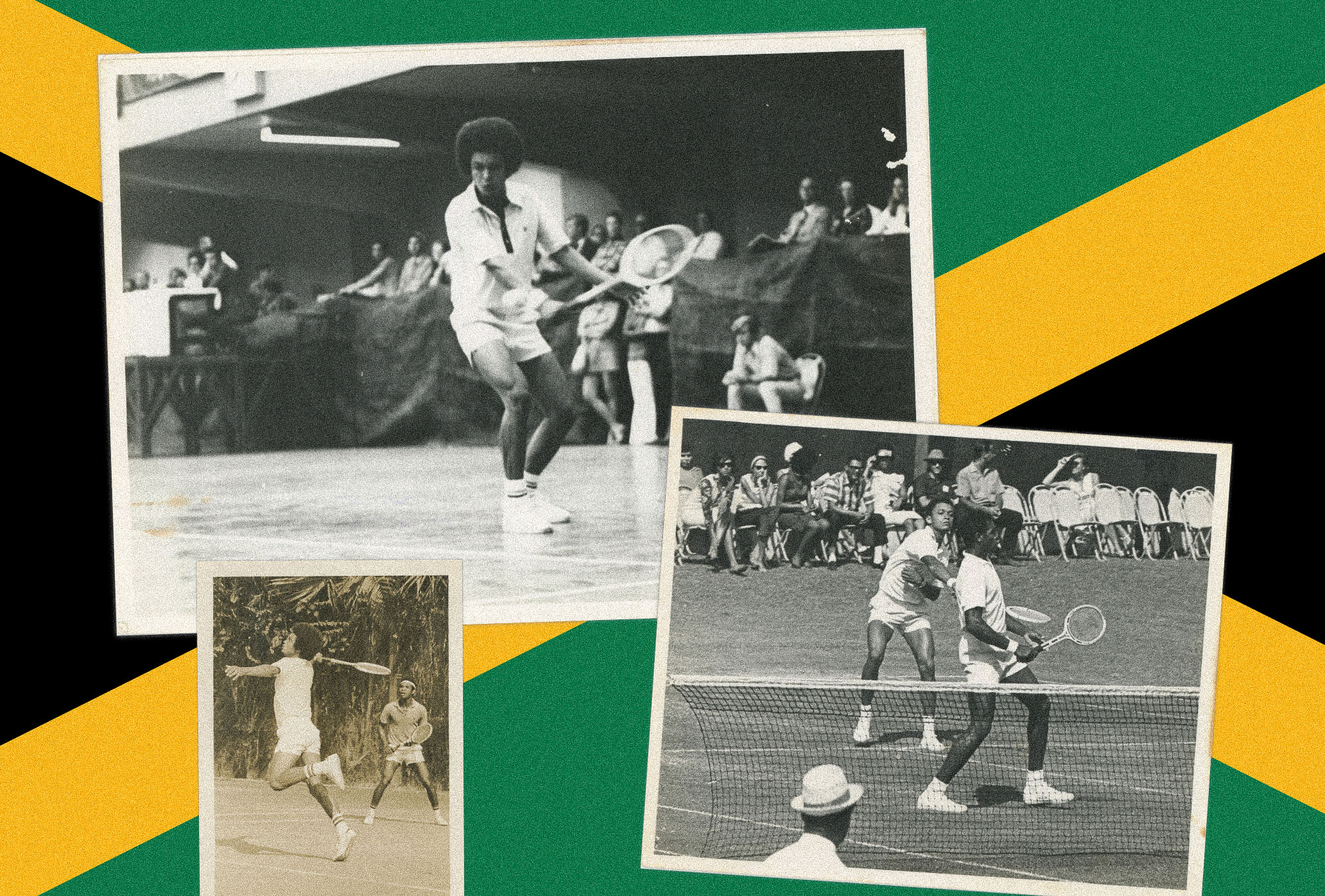

Peak Richard Russell in Jamaica (bottom right with doubles partner Lance Lumsden). //Courtesy of Compton Russell

Peak Richard Russell in Jamaica (bottom right with doubles partner Lance Lumsden). //Courtesy of Compton Russell

Richard Russell, an athletic Jamaican teenager, was on track to become a cricket star of the 1960s for the West Indies—or so he thought, until one day he was plucked off the cricket field at his high school, Kingston College, by a teacher who needed players for the school’s undermanned tennis team.

Once he showed potential on court, the tennis coach entered him in the Jamaican National Tennis Championships; he reached the final.

From there, Russell—and his family—rebuilt their lives around tennis. His father, Irving, scuttled long-held plans to build a swimming pool at the family home in Kingston, installing a tennis court instead. His mother, with some annoyance, had to replant her imported roses on another side of the house to make room.

“At 21 Wellington Drive, Kingston, Jamaica, that became the Russell House of Tennis,” Compton Russell, a nephew of Richard’s, told me. The home court was convenient but compact; its perimeter was well below regulation size. “Bro, the runback was about five feet short on each side,” Compton said, laughing.

But the small concrete rectangle was big enough to become a launching pad: Richard developed into Jamaica’s national champion and the best player in the Caribbean. The question, though, was where to go into orbit. Peter Scholl, a German coach who was a protégé of Gottfried von Cramm’s, had been in Jamaica for a spell, but Russell would need to leave the island to find his potential. The rampant segregation still present in the nearby United States made an American path a less viable option.

Seeing how the best players in the world were Australian, Irving Russell cold-called—after being patched through several operators across the world—legendary Australian coach Harry Hopman, telling him he was the father of the Jamaican national champion who had nowhere to train. Hopman said to send Richard over to Australia, and so Richard went.

“He goes to Australia, and Harry Hopman falls in love with him,” Compton Russell recalled.

Richard Russell lived in Hopman’s Melbourne home for a year. His letters back home—which took weeks to arrive—recounted training sessions with Laver, Emerson, Newcombe, Sedgman, and more. So sublime was Russell’s technique on his Eastern-grip forehand and one-handed backhand, Hopman even wound up using Russell as a model in some of his instructional videos. After Australia, the entire world of tennis was open to Russell, and he charted his course.

“His legacy to me is the fact that he really had the courage to go out there and play in the early days when there was no guarantee that anybody could make a living out of playing tennis,” David Tate, a Jamaican who was an early tour companion of Russell’s, told me. “He was a pioneer.”

Making a lucrative living playing tennis was expressly forbidden in those days, in fact, as the most prestigious tournaments remained closed to professionals. So to keep the tennis dream going, the Russell family back in Jamaica hosted barbecue fundraisers on the family tennis court. There was even a sort of proto-crowdfunding: an ad placed in a Kingston newspaper saying that Russell was accepting donations.

“I remember his dad talking about second mortgages,” Compton Russell told me. “Just to get some money, a loan, for air tickets and hotels.”

The Russell hustle back home was propelling a player who, despite modest results, was becoming one of the most beloved players on the traveling tennis tour. To have some fun and make some extra cash on the road, Russell agreed to join his compatriot Lance Lumsden in a musical duo that performed at various stops along the tour, with a signature song called the “Tennis Twin Medley.”

In those years predating the ATP rankings, tournament invitations often largely focused on national and regional champions; Russell, as the best of the Caribbean, got invited to the biggest tournaments. He won a decent share of his matches, too, including a main-draw match at each of the four majors.

“He beat some really well-recognized players,” Compton Russell told me, suggesting an analogue: “In today’s game, Richard would have had a win over somebody like a Tsitsipas.”

The flashiest win on Russell’s résumé came in doubles: In 1966, Russell and Lance Lumsden pulled off a considerable upset in a live Davis Cup doubles rubber in a zonal match in Kingston against the Americans, beating Arthur Ashe and Charlie Pasarell 6–4, 7–9, 14–12, 4–6, 6–4.

Ashe and Russell were easily lumped together as the two top Black players on the circuit; one article in The Louisiana Weekly introduced Russell as “the world’s second ranked black tennis player,” behind Ashe. (“The handsome champion of the West Indies is a speed demon on the court with his ‘Go for broke’ style,” it added.)

Russell was often mistaken for Ashe by autograph seekers at tournaments and learned it was easier if he just signed “Arthur Ashe” without making a fuss. But Russell and Ashe also formed a genuine friendship; Ashe visited Russell in Jamaica multiple times.

Some of Russell’s visits to America, though, proved more challenging in the mid-1960s. One tournament in Pensacola, Fla., held an emergency board meeting to decide whether or not to let this Black Jamaican man play at their all-white club.

“They decided that I’m not an American, I’m Jamaican, and those are the grounds on which they allowed me to play,” Russell told BlackTennisPros.com decades later, upon the occasion of his induction into the Black Tennis Hall of Fame.

Compton Russell recalled Richard sharing a more menacing memory. At a tournament in the Carolinas, Richard was sitting in the back seat of a car, being driven home by the white daughter and son of his host family at that week’s tournament.

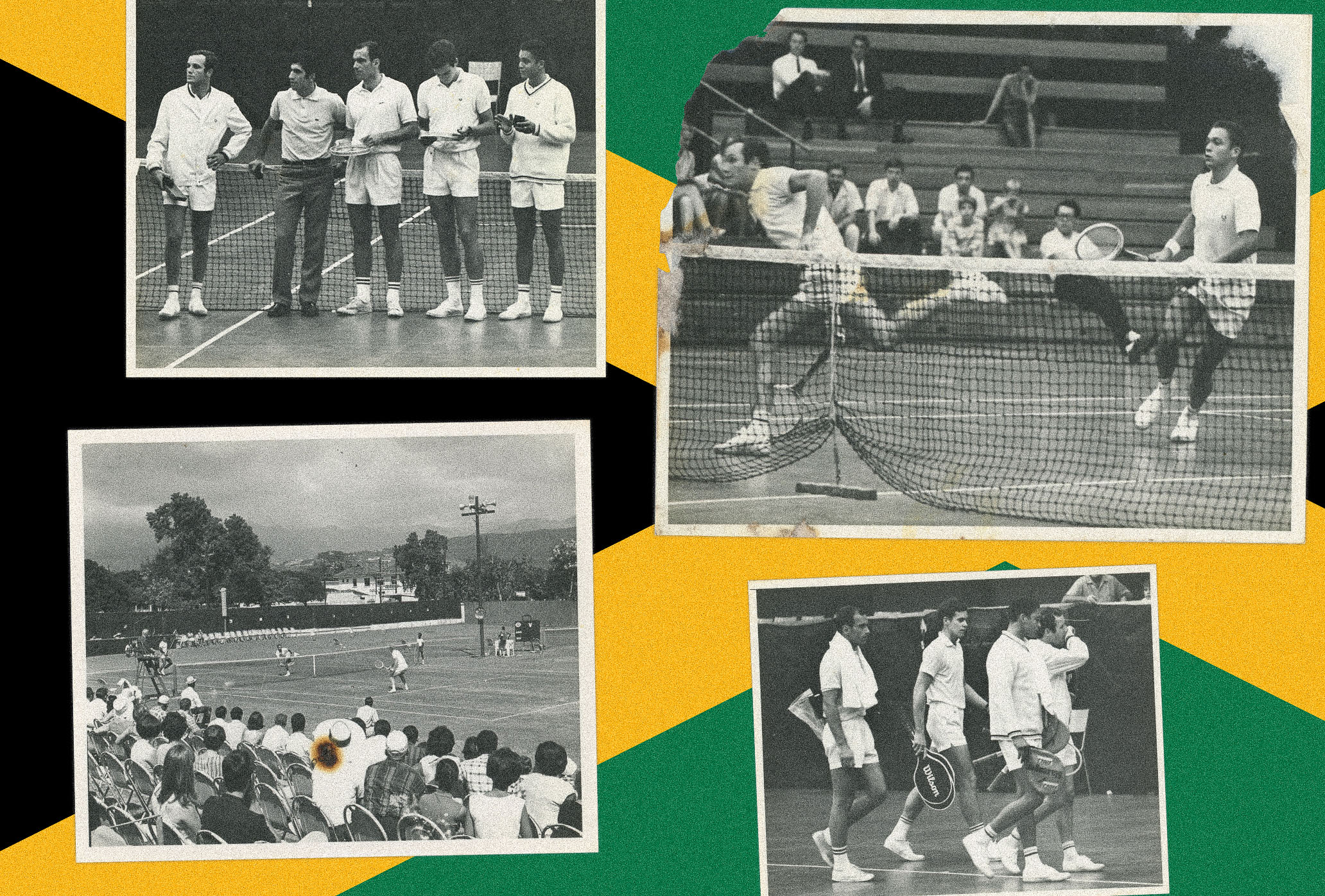

Richard Russell (far right) at the pro tournament he helped organize at the National Arena in Kingston in the early 70s. Top right: with doubles partner Tom Okker. Bottom left: tennis on the old grass courts at the St. Andrew Club in Kingston. // Compton Russell

Richard Russell (far right) at the pro tournament he helped organize at the National Arena in Kingston in the early 70s. Top right: with doubles partner Tom Okker. Bottom left: tennis on the old grass courts at the St. Andrew Club in Kingston. // Compton Russell

“They stopped at a red light, and a car pulled up beside him,” Compton told me. “The other car was packed with guys, and they rolled the window down and started yelling. The girl was driving the car. She took off, and the car started following them. They raced around for two or three miles, pulled in the driveway of the house. And as they pulled into the driveway of the house, the brother and sister jumped out of the car. The other guys pulled right on the roadside beside them.”

The sister and brother, Compton recounted, told Richard to stay in the car as they jumped out to talk down the threatening group: “They explained: ‘He’s not an American; we’re hosting him for a week, and it’s okay. You’d be very wrong to attack him or persecute him. He’s protected. He’s an international athlete. And if anything happens, it’s going to be a big problem.’ And they drove away.

“He only told me a few stories like that,” Compton added. “He never really focused on it in a sense. He was tennis, tennis, tennis, tennis, tennis, tennis, you know?”

Because within the world of tennis, life was pretty good for Richard Russell. Compton, eight years younger, joined Richard on the tour in the early ’70s and got to see his magic up close.

“That’s when I see the aura,” Compton said. “I’m tagging along, and I’m in awe. The tournament directors, the players, the tournament referees, the linesmen, the hosts, the families: ‘Richard, you’re back! So nice to see you, Richard! Oh man, what are you doing later? You’ve got to come to dinner. We’ve got to have lunch.’ All that love—he was larger than life. A bright light.”

Richard’s status as a role model spread beyond his family, beyond Jamaica, and to the rest of the Caribbean commonwealth islands, who used to compete together as one Davis Cup team at that time.

“It meant everything because it showed that one of us could do it,” Mike Nanton of St. Vincent told me. “He gave us a goal to move towards, knowing that we could get there too.”

John Maginley, an Antiguan, said that Russell was “everything I wanted to be.”

“Just his presence, the way he carried himself on the court, off the court,” Maginley said. “He was always immaculately dressed. Spoke very well. Carried himself very well. You never heard of Richard Russell being in anything crazy, in any trouble.”

Maginley and others described Russell as their “icon,” but one who was always approachable and engaged with their own fledgling careers.

“Very simply put, he wasn’t a snob,” John Antonas of the Bahamas said of Richard. “He shared everything. In tennis, when Richard was good, things weren’t quite as they are today; everybody there, they shared everything. We were a family.”

Russell was on the ground floor when men’s professional tennis was being built into a towering business: He became a founding member of the Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) when it was created in 1972, a calling card that remains a point of pride for Jamaican tennis.

But the shift toward commercialism wasn’t always what he wanted. With his more laid-back approach, Russell grew weary as the Open Era and rankings arrived and the tour became more professionalized, competitive, and demanding. He decamped home for a lucrative coaching gig in Half Moon Bay in Montego Bay; his $100-an-hour lessons were described by one as “like celebrity hour.” He once ushered the professional tour to his own island home, hosting a 1978 WCT Tournament in Montego Bay that featured top stars like John McEnroe and Ilie Nastase.

But while he was giving lessons to vacationing millionaires like the Bronfman family, who founded Seagram’s, Russell also found ways to foster local talent. He initiated a program where kids could make $1 an hour being ball boys and ball girls during the lessons; when the courts weren’t in use by resort guests, the kids were free to play on their own.

“That’s how a lot of us got good,” Maureen Rankine told me. Rankine said her family, “from our neighborhood, didn’t belong in tennis.” But with Russell’s support, she and four of her siblings from the “wrong side of the tracks” went to colleges in the U.S. on full tennis scholarships.

Richard Russell soon had his own sons, Ryan and Rayne, whose tennis-playing careers he wanted to develop. In order to help his sons thrive, Richard organized a bevy of small professional tournaments in Jamaica, as many as 22 in 2002, striking deals with various hotels around the island. The biggest beneficiary, as it happened, was from outside his own family.

“Everything was made available by Mr. Russell for the sons,” Dustin Brown told me. “And yeah, I was fortunate enough to be around, to also be under the wing, almost, just gliding and trying to take all this stuff that could help my career.”

Brown, who switched to representing Germany and later switched back to representing Jamaica at the end of his career, would go on to be the region’s best player of this century, highlighted by a thrilling win over Rafael Nadal in the second round of Wimbledon in 2015.

“Who knows what would have happened if those Futures wouldn’t have been in Jamaica?” Brown told me. “Maybe it would have been no Dustin Brown—you never know.”

Brown said that he hadn’t known of Richard Russell’s own playing career until it started being mentioned in articles to contextualize his own milestone wins at majors. “He was very chill, friendly, and calm,” Brown recalled. “But you knew that he had a lot of pull in Jamaica.”

Another future star had a start in Russell’s Jamaica too. In 2011, just before her 14th birthday, Naomi Osaka traveled from her home in Florida to make her debut at a $10k tournament Russell had organized in Montego Bay. I spoke to Richard in 2022 as I researched a biography of Osaka. He apologetically said he didn’t remember Osaka’s appearance well—not surprising since she lost in the first round of qualifying—but said he took pride in what she’d become from her own Jamaican launching pad.

“We were very pleased and pleasantly surprised and very, very happy that a player like her came to Jamaica early and then became a world-class player,” he said.

In our conversation, Russell told me that girls were going to be a focus of his going forward. “I got a call last year from a tennis coach at a college in Louisville, Kentucky, asking me if I have any female Usain Bolts playing tennis,” Russell said, laughing. “And that was very funny. We recognize now we want to focus first on very athletic female youngsters and introduce them to tennis. I think that’s where we’re heading, as a small country.”

Russell was recovering from two cancers when we spoke, he told me, but he remained driven and full of plans for future ventures. Maureen Rankine, who described herself as Russell’s “His Girl Friday,” said that up until his death, Russell had “plans to continue doing things big.”

Richard Russell died from pneumonia on Jan. 15, 2025, in Montego Bay at the age of 79. His funeral, with an all-white dress code in a nod to Wimbledon, will be held on March 1.

His passing has rekindled email chains and memories among the men whom Russell played alongside across the Caribbean, many of whom have now dispersed to other parts of North America.

“Whatever you write about Richard, put in there that the guy was loved by his fellow guys,” John Maginley told me. “I think that’s the most important message, that we’re in awe of all that he did.”

The Hopper

—CLAY Tennis on Beatriz Haddad Maia’s US Open run.

—Giri on Iga Swiatek’s loss to Jess Pegula.

—Jon Wertheim’s mailbag is full this week.

—Sara Errani and Andrea Vavasori have won the US Open mixed doubles.

—Tim Newcomb on Taylor Fritz and Asics.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Walking Tall

Walking Tall

Walking Tall

Diego Schwartzman forced the issue.

Diego Schwartzman forced the issue.

By Giri Nathan

February 20, 2025

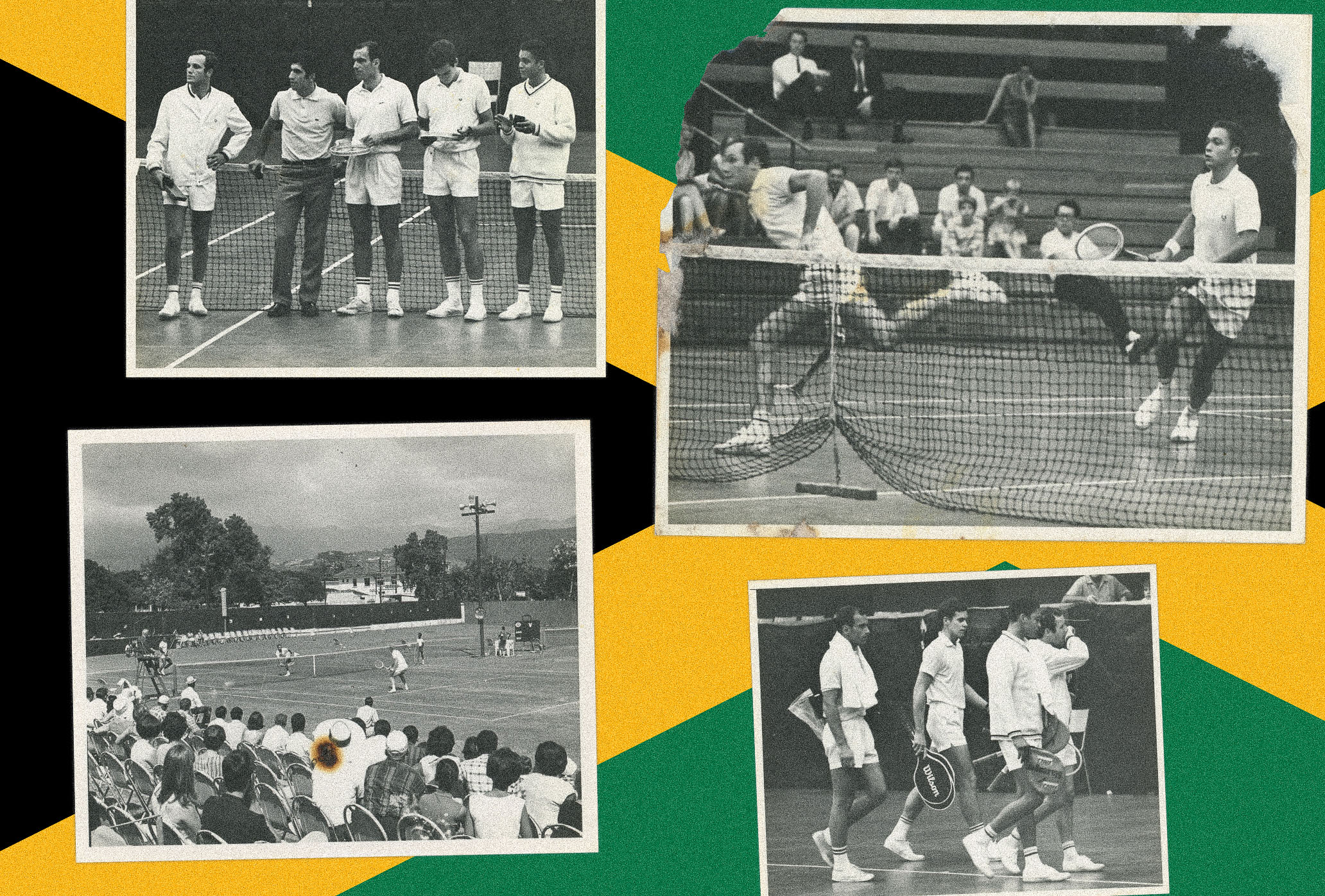

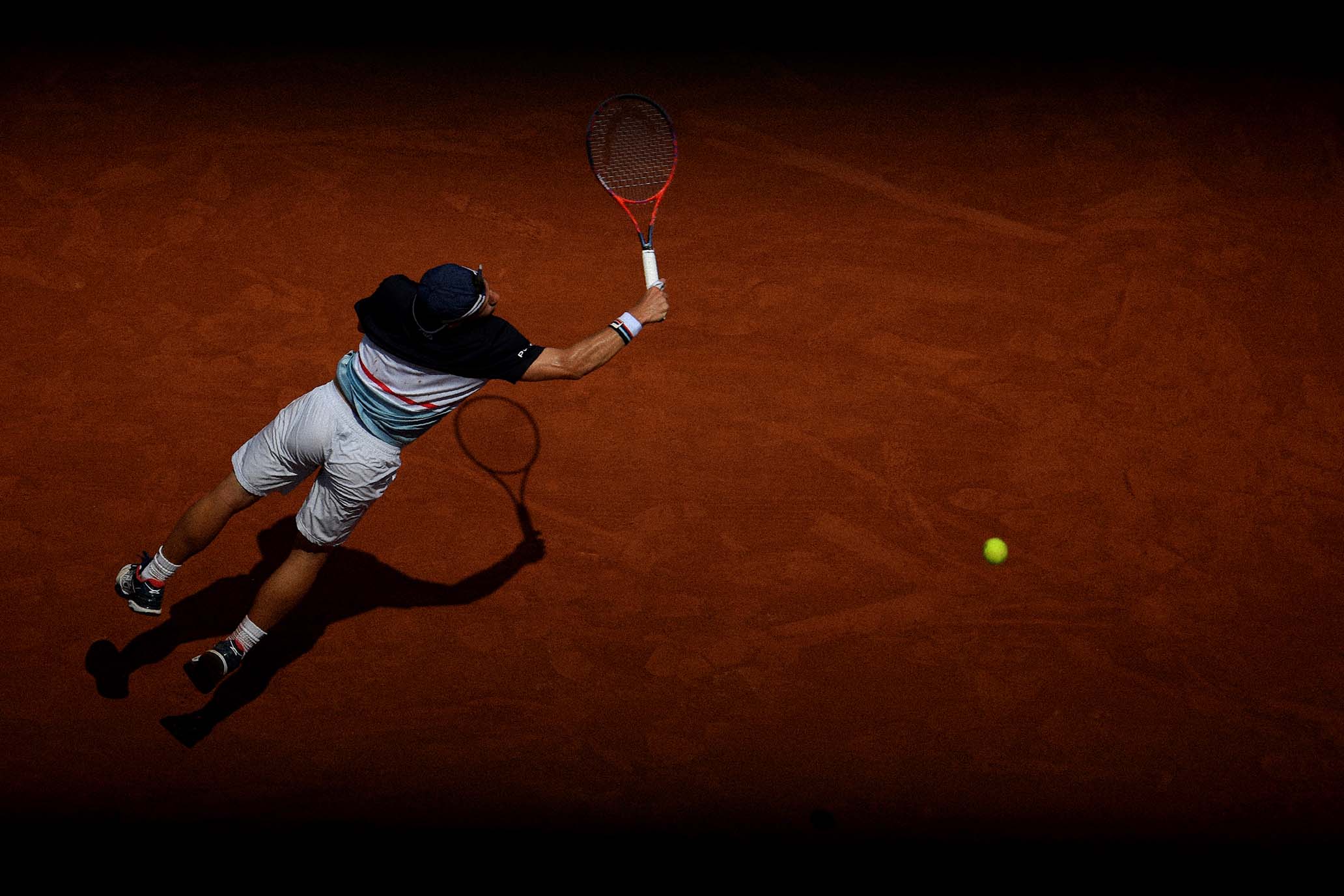

Diego Schwartzman takes flight at Roland Garros, 2018. // Getty

Diego Schwartzman takes flight at Roland Garros, 2018. // Getty

Imagine, 50 years from now, looking back at the current era of the ATP, but seeing its players only as outlines, shadows cast against a paper screen. You’re trying to remember who is who. Many of those silhouettes would be lost to time; you’d lived plenty of life since then. Plenty more would seem interchangeable, as there are so many ATP players with roughly the same proportions, to say nothing of their same-ish styles of play. But one silhouette would be unmistakable. The racquet, dangling at rest, almost grazes the ground. A backwards hat sits on top of his head. He seems like he’d have to strike most balls at head height. There’s no mistaking Diego Schwartzman, who retired from tennis last week. He looked like no one else out on the court, and his tennis looked like nobody else’s tennis.

On a tour dominated by fast serves struck from high vantage points, and powerful ground strokes levered by long arms, Schwartzman was an outlier, officially listed at 5 foot 7. When I had a chance to hang out with him for a profile a few years ago, I realized that figure was probably two inches overstated. Quite often, at the coin toss or at the handshake, Schwartzman was clearly a full foot shorter than his opponent. And during his peak, which began at the end of 2017 and ran through 2021, he could beat almost all of them. In 2018, when he first entered the top 10, he was the shortest player to do so in 37 years.

Most of the shorter players in the sport opt for a counterpuncher’s style, patient and opportunistic. Schwartzman, meanwhile, was thrilling because of how persistently he forced the issue. He was short, but such an explosive athlete that he could access power anyway. And he played with a racquet that was two inches longer than the standard, the maximum length permitted on tour, which extended his reach and leverage. He used an extreme semi-western grip on his forehand that made it easier to manage high balls. On the flip side, it can be harder to deal with low balls—fortunately not an issue for Diego, who could easily meet them where they were. His return was among the best in the world; for six seasons he landed in the top three in percentage of return games won. The serve was weak, sure, but once the rally had gotten to neutral, he was as pure a ball-striker as anyone alive. To me this was one of the greatest sights in this or any sport: the diminutive Argentine, hurling himself off the clay to hit a high-bouncing ball about six feet high and plucking a winner out of the air.

Diego in tennis paradise, 2021 // David Bartholow

Everything he accomplished, he did it by outhitting his opponents from the baseline, no cheap points. And in time all the qualifiers fell away; he wasn’t just good on clay, he wasn’t just good for a short guy, he was just plain inarguably good, with an excellent résumé: the No. 8 ranking, four titles, and deep runs at the Slams (four quarterfinals, one semifinal). His most memorable match, for many fans, might even have been a loss. Back in 2018 he went up a set and a break on Rafael Nadal at Roland-Garros, looking as good as anyone ever had against Rafa on Court Philippe-Chatrier, putting him in a peril that very few players managed over a two-decade span. Then rain suspended play. Nadal came back the next day and won. But two years later, in Rome, Schwartzman did add his name to the prestigious list of players who managed to beat the king of clay. In one interview he told me that he could feel himself accumulating respect in the locker room with every big win he pulled off on the court.

Once you got to know Schwartzman’s backstory—his upbringing in poverty during Argentina’s economic depression—you could see that his success was statistically unlikely in ways beyond just the height. He’d had to work. But he bristled at having his success reduced to mere persistence. He was also, it bears reiterating, an otherworldly talent. Persistence alone won’t get you a first step that fiery, or a touch that soft. I liked how he put it in a recent first-person retirement essay: “Just being a fighter does not get you to the top. I was there because I was good at this sport. Nobody gave me a gift. I earned this.”

In that same essay, Schwartzman identified the precise moment of his decline. During a match at Hamburg in 2022, he felt an unfamiliar sensation, cramping and shaking. That feeling persisted and his results never recovered. He fell out of the top 100 the next season. Here was another reminder not to take any of your favorite players for granted. For a time, Diego and his close friend Dominic Thiem played brilliant matches against each other, and both men seemed like they’d be tour staples for years to come. As it turned out, their primes were stunning but brief. Neither man extended his success into his 30s, and both retired at ages that might as well be mid-career in the contemporary game.

Schwartzman announced that he would hang up his racquet, at age 32, at his home tournament in Buenos Aires. He’d won the title there in 2021 without dropping a set. Heading into last week, Schwartzman had barely played at all in the prior six months, just one Challenger match—a loss—to tune up for his last stand. There, Schwartzman produced one final miracle: a three-set defeat of the No. 40, the big-serving Nico Jarry, extending his career one more match. That was about as far as he could go. In the final points of his very last match, against Pedro Martinez, Schwartzman was cheered by the entire stadium. The umpire tactfully let them sing their hearts out before eventually cutting it off. There were tears in Schwartzman’s eyes during those last few rallies. His peers, too, sent him off in a chorus of praise. Holger Rune remembered the time, as a rookie short on cash, that Schwartzman walked up and paid for his food. We may never again see a top 10 player quite like him. The man known as El Peque can have the last word: “I have a small body, but it gave the biggest players in our history bad moments.”

The Hopper

—CLAY Tennis on Beatriz Haddad Maia’s US Open run.

—Giri on Iga Swiatek’s loss to Jess Pegula.

—Jon Wertheim’s mailbag is full this week.

—Sara Errani and Andrea Vavasori have won the US Open mixed doubles.

—Tim Newcomb on Taylor Fritz and Asics.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Mixed Results

Mixed Results

Mixed Results

The U.S. Open shakes up the mixed doubles format.

The U.S. Open shakes up the mixed doubles format.

By Ben Rothenberg

February 13, 2025

Taylor Townsend and Donald Young, runners up in the US Open mixed doubles draw in 2024, the last of its kind. // Getty

Taylor Townsend and Donald Young, runners up in the US Open mixed doubles draw in 2024, the last of its kind. // Getty

All sorts of Olympic sports—archery, curling, judo, sailing, shooting, swimming, track, and more—have contrived newfangled mixed formats in recent years because of how dynamic and appealing mixed-gender competitions are considered to be. Tennis, meanwhile, was invented with mixed doubles already at the forefront: One of my favorite factoids is that when Major Walter Clopton Wingfield published the first set of lawn tennis rules back in 1873, the lone illustration in the rule book depicted a mixed doubles match.

But instead of adding new trophies, mixed doubles has been atrophying.

It’s evident what makes the public care about mixed doubles: the participation of singles stars. It’s that simple. There have been two spotlight moments for mixed doubles in the past decade, and both involved Serena Williams and a member of the Big 4: when she played against Roger Federer in the 2019 Hopman Cup, and when she partnered with Andy Murray to play the mixed at Wimbledon later that same year.

But those were unicorn events, and as singles stars opt out over and over at the majors, doubles—both same-gender and mixed doubles—has steadily become the domain of an increasingly separate population of players: doubles specialists. And doubles specialists have consistently not been able to generate crowds or attention or value for the biggest tournaments.

The U.S. Open, to its credit, recognized this reality. Rather than mindlessly running another irrelevant, dead-weight mixed doubles competition this year, the U.S. Open believed enough in the potential of mixed doubles to breathe life into the format with a radical revamp, as they officially announced Tuesday after weeks of leaks:

“TENNIS’ BIGGEST STARS WILL HAVE AN OPPORTUNITY TO COMPETE FOR A COVETED MIXED DOUBLES GRAND SLAM TITLE, A MULTI-MILLION DOLLAR PURSE AND A $1 MILLION PRIZE.”

Instead of taking place during the final week of the tournament, when all the biggest stars are laser-focused on late-round singles matches (or already on flights home if they’ve lost), the mixed doubles competition will be an amuse-bouche before the main draw, taking place on the Tuesday and Wednesday before the tournament. Instead of being shunted to the outer courts, mixed doubles matches will be held exclusively at Arthur Ashe Stadium and Louis Armstrong Stadium. And instead of mixed doubles champions being paid peanuts, there will be $1 million for the winning pair, and an overall prize purse in the millions.

To make participation less daunting on the eve of a major, matches will be streamlined into best-of-three-set matches with short sets to four games, no-ad scoring, tiebreakers at 4–all, and a 10-point match tiebreak in lieu of a third set. The final will be a more standard-length mixed doubles match, a best-of-three-set match with sets to six games, no-ad scoring, tiebreakers at 6–all, and a 10-point match tiebreaker in lieu of a third set.

The biggest change: Instead of being contested almost entirely by doubles specialists who haven’t captured the public’s attention or imagination in previous editions, the draw will largely be filled with singles stars. The U.S. Open mixed doubles field will be made up of 16 pairs, with eight entries based on singles rankings only—rather than singles or doubles rankings as it was previously—and the other eight entries being wild-card teams.

Taylor Fritz and Jessica Pegula, the two runners-up in the U.S. Open singles draws last year, both indicated a desire to participate in the U.S. Open’s press release on the new reformatting.

The complaints from traditionalists—and doubles specialists outraged at being shut out—have been predictable and, I think, easily shot down. Most prominently, the reigning U.S. Open mixed doubles champion pair of Andrea Vavassori and Sara Errani put out a statement calling the new format a “pseudo-exhibition.” But surely mixed doubles at majors, by not giving ranking points, already met the most common definition of an exhibition event? Although if mixed doubles was an exhibition event before, admittedly, it was a bad one: Exhibition events are designed to draw crowds and sell tickets to see stars, and those star players collect big paychecks for participating; mixed doubles at majors hasn’t met any of those appealing criteria for a long time. If mixed doubles has become a bona fide “exhibition” event with this change, that’s an upgrade from the afterthought it was before.

Vavassori and Errani also cited “tradition and history” as reasons for keeping things the old way. But the meaningful “tradition” of mixed doubles, historically, wasn’t to assure that no one gave a shit about it, which is all a lack of change would accomplish with the current trajectory of the category. To be more blunt, the idea that a mixed doubles title was something worthy of the “Grand Slam” label in its recent iterations has seemed increasingly hollow as the mixed doubles fields grew weaker and more anonymous, and as the pay gulf became so stark as a result.

There’s been a lot of pity for doubles specialists on social media since this announcement—much of it from the doubles specialists themselves—and I don’t think that will prove helpful to their cause. What would be helpful, I think, is for this to be a wake-up call. If this comes off as harsh toward doubles specialists, it’s meant to: I think they’ve had their chance to prove themselves as attractions for years now—especially with every doubles match now fully produced and available to stream—and they’ve consistently shown that they cannot. The idea that the U.S. Open should maintain a system of handouts or charity for doubles specialists rather than revamp the mixed doubles event into something worthy of being showcased at a Grand Slam is unconvincing, especially because the prize money for the event that they’re whining about missing out on was so paltry compared with the more-than-quadrupled amount the tournament thinks mixed doubles can be worth now.

My hope is that the U.S. Open deciding to make mixed doubles into something that people will watch and care about—and how they determined the best way to do that—will light a fire under the complacency of doubles specialists about their places in the business model of the sport, if they care enough to fight for it. And even without learning to win singles matches, there’s still a way into the mixed doubles draw: They can learn to become entertaining, compelling, and popular enough in the next few months to convince U.S. Open organizers that they should be awarded some of those wild-card entry spots.

If they can do that, the sport will be stronger for it, and everyone will win big.

An expanded version of this story can be found at Bounces, Ben Rothenberg’s new Substack newsletter about the world of professional tennis, which you can subscribe to here.

The Hopper

—CLAY Tennis on Beatriz Haddad Maia’s US Open run.

—Giri on Iga Swiatek’s loss to Jess Pegula.

—Jon Wertheim’s mailbag is full this week.

—Sara Errani and Andrea Vavasori have won the US Open mixed doubles.

—Tim Newcomb on Taylor Fritz and Asics.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Wilson Drops Marta Kostyuk’s New Intrigue

Wilson Drops Marta Kostyuk’s New Intrigue

By Tim Newcomb

February 11, 2025

Image courtesy of Wilson

Images courtesy of Wilson

Wilson’s premier head-to-toe athlete, Marta Kostyuk, has been sporting a version of an on-court tennis shoe she’s helped design since the 2024 U.S. Open. She even wore a player-edition colorway for the 2025 Australian Open. Now Wilson is preparing the retail release of the women’s-specific Intrigue this month.

“Focusing on a women’s-specific design was our main goal from the very beginning,” Tate Kuerbis, Wilson senior director of footwear design, tells me about the project. “To do this correctly, we started working immediately with our head-to-toe athlete Marta Kostyuk.”

Kostyuk helped lead the design from every step, giving the Intrigue a narrower heel and more generous forefoot fit needed for a female player. Designers also added additional comfort underfoot from the start. The Intrigue features three new technologies for Wilson, including an engineered mesh upper, a lacing system meant to allow customization, and a thicker sockliner focused on cushioning.

The new Intrigue lineup will feature a Tour, Pro, and Lite version, each with differing price points. Kuerbis says the Lite may double as both a casual performance and off-the-court style. Kuerbis calls the aesthetics of the Intrigue lineup clean, modern, and simple. His goal was to create “iconic and timeless designs that can stand the test of time, especially for a legacy company such as Wilson.”

The Intrigue name ties back to a line of women’s-focused tennis products Wilson launched in 1992. That 30-plus-year-old lineup even included a shoe. So, even while the new Kostyuk-led lineup may borrow a name from the ’90s, everything else about the Intrigue comes fresh for 2025.

Follow Tim Newcomb’s tennis gear coverage on Instagram at Felt Alley Tennis.

SIGN UP — YOU'RE ONLY AS GOOD AS YOUR SECOND SERVE.

SIGN UP — YOU'RE ONLY AS GOOD AS YOUR SECOND SERVE.

Dynamism & Struggle

Dynamism & Struggle

Dynamism & Struggle

Simona Halep didn’t always make it look easy.

Simona Halep didn’t always make it look easy.

By Giri Nathan

February 7, 2025

Simona Halep calls it a day in Cluj-Napoca. // Getty

Simona Halep calls it a day in Cluj-Napoca. // Getty

I had been expecting a slow but steady Simona Halep comeback. Not a sudden retirement this week at age 33. But this last phase of her career has been sad and murky, at every turn, so this fits.

In 2022 she hired Patrick Mouratoglou as coach, which was followed soon by poor results, an on-court panic attack, and a public Instagram apology from Mouratoglou for those poor results. Later that year she made a Wimbledon semifinal and returned to the top 10. But she also received a provisional suspension after tests revealed the banned substance roxadustat—which Mouratoglou also eventually apologized for, since his team gave her the tainted collagen supplement. In 2023 there was the full-on doping suspension for irregularities in her blood samples over time. Then in 2024, after an appeal, that was shrunk from four years to nine months as she was found at “no significant fault or negligence” for the adverse test result.

After all that, she returned to the court as a wild card in Miami 2024 and immediately went three sets with Paula Badosa. That’s what had me suspecting a comeback. It was misleading. That was the last time she’d ever get remotely close to beating a player of her own stature. She played just five more matches in total, and won one. She said this week that she has been unable to recover from her injuries, in particular one to her knee cartilage. Thus, a brief retirement speech, in her home country of Romania, at the WTA 250 in Cluj-Napoca.

It’d be a shame if this dismal coda made people misread what is pretty clearly a Hall of Fame career. To pierce through the gloom, just return to memories and footage of Halep at her peak, from 2017 through 2019, as one of the most adept counterpunchers ever to play in the WTA. A short-statured, compact player, Halep ricocheted all over the court like a flung Super Ball. With her explosive first step and ease recovering from the corners, her court coverage could confound any opponent. Other people’s power didn’t bother her—she loved to redirect their pace—and her own low power was no problem. She simply figured out how to hurt her opponents in situations where they thought it impossible to get hurt. Even while careening from one sideline to another she could throw her full body weight into punishing counterattacks. Halep is an all-time elicitor of where did that come from?

One theme of her early career, though, was some reticence when closing out big matches. She lost her first three major finals, all in three-setters. Most conspicuously, Halep lost the 2017 Roland-Garros final despite being up 6–4, 3–0, to an unestablished teenager; the upside of that is that we can now say “Grand Slam champion Jelena Ostapenko.” Less troubling, but also disappointing, was her valiant 2018 Australian Open, where she played her way to the final on an ankle she had grotesquely injured earlier in the tournament, and lost narrowly after a defensive master class against Caroline Wozniacki.

At the next major in 2018, Halep arrived at Roland-Garros to rectify last year’s result. At that point she was world No. 1, in her prime at age 26, with $26 million in prize money, a fresh Nike deal, and still without a major title. She fell down a set and a break to Sloane Stephens in that final. And then, as she explained later, she remembered that she’d been on the opposite end of that score line the previous year. So she knew that a recovery was possible. She won that final by remembering how she lost it.

With her second major win, there was less intrigue, because she delivered arguably history’s cleanest performance in a major final. This was at Wimbledon in 2019, despite facing the tournament’s seven-time winner in Serena Williams. Halep dismissed her in 56 minutes, only hitting three unforced errors, a near-mystical performance. Halep, listening to audio from that championship point this week, said it was the most important and beautiful match of her career.

She didn’t always make it look that easy. Her matches were thrilling precisely for that reason, for all the dynamism and struggle. “I don’t want to cry. It’s a beautiful thing,” she said in her retirement speech, in Romanian. “I became world No. 1, I won Grand Slams. It’s all I wanted. Life goes on.”

The Hopper

—CLAY Tennis on Beatriz Haddad Maia’s US Open run.

—Giri on Iga Swiatek’s loss to Jess Pegula.

—Jon Wertheim’s mailbag is full this week.

—Sara Errani and Andrea Vavasori have won the US Open mixed doubles.

—Tim Newcomb on Taylor Fritz and Asics.