The 2026 Australian Open Shoe Report

The 2026 Australian Open Shoe Report

The 2026 Australian Open Shoe Report

Our favorites for performance, lifestyle, and everything in between.

Our favorites for performance, lifestyle, and everything in between.

By Tim Newcomb

January 23, 2025

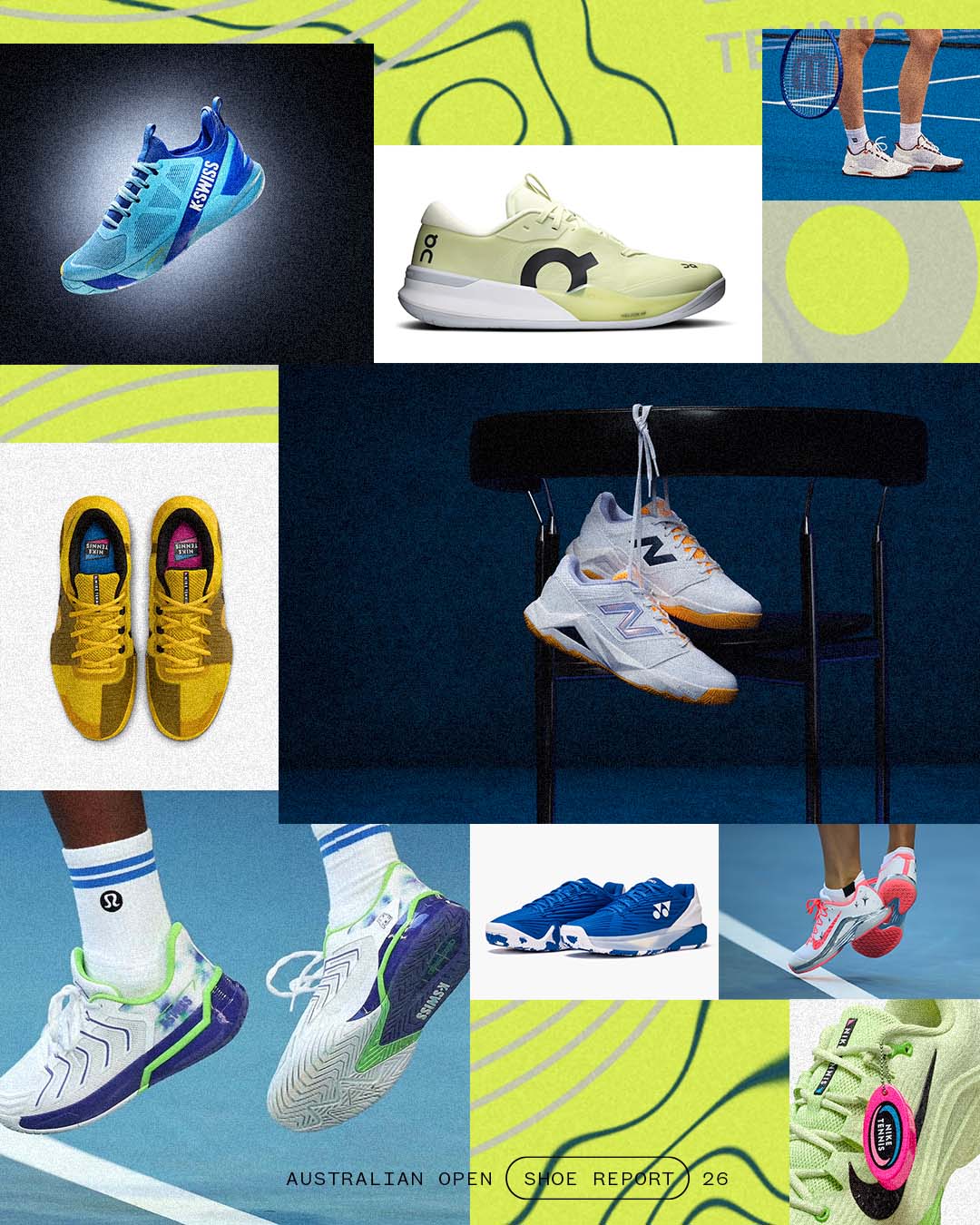

It’s all about Melbourne-themed collections and tournament-specific colorways in the 2026 Australian Open shoe closet. Coco Gauff leads the way with her signature shoe, and while a few players and brands—such as K-Swiss with Andrey Rublev and Frances Tiafoe, and Nike with Naomi Osaka—have special Australian Open player-edition models, many athletes are simply sporting their sponsor’s inline colorways for the tournament.

Most majors tend to have a color or two that a few brands latch on to (unbeknownst to each other, of course), but the AO 2026 is a smorgasbord of brightness, with neon yellow, orange, red, blue, and purple all part of the array.

New Balance CG2

Coco Gauff

Coco Gauff says her AO kit design isn’t just concerned with performance, “but also about style and self-expression.” Her signature CG2 on-court shoes from New Balance play to that theme with a colorway inspired by the Australian landscape meant to “radiate optimism” with hot marigold (think bright orange), navy blue, and daybreak periwinkle. Gauff says that, paired with her perforated stretch tank and pleated skirt in either a subdued purple or a strong orange, the entire kit shares her “love for bold colors and the beach.”

K-Swiss K-Frame Speed Rublo

Andrey Rublev

K-Swiss is embracing player-edition shoes aplenty in Melbourne. The brand revealed Andrey Rublev’s signature K-Frame Speed Rublo in a Baltic Sea (light blue), dazzling blue, and white colorway, while most of the other K-Swiss players are wearing the Hypercourt Pinnacle or Ultrashot 4 with the same colors reversed.

Nike GP Challenge 1.5

Jannik Sinner

Jannik Sinner has gone in a different color direction. His Nike GP Challenge 1.5 Premium shoes have a brown-yellow colorway, listed on the brand’s retail site as “saffron quarts/olive flak/sail/black,” and feature a custom tongue design that calls out his past championships. The new GP Challenge 1.5 Premium offers slight tweaks on the first model, mostly with a touch more room in the forefoot (by tweaking the Air Zoom design, Nike says), additional durability on the upper around the toes, and a gusset on the tongue to keep it in place.

K-Swiss Killshot 4

Frances Tiafoe

Frances Tiafoe still doesn’t have an official deal with K-Swiss, but that hasn’t stopped the brand from cranking out player-edition model after player-edition model for the American since he started pairing his Lululemon apparel with the shoes in January 2025. This year, the Ultrashot 4 “Big Foe Aus Open” features white, “wild bluebell,” and “frond” with a special “Big Foe” graphic on both the tongue and the upper.

On Roger Pro 3

Ben Shelton

Ben Shelton is sporting the as-yet-unreleased On the Roger Pro 3 in a light yellow with white, officially known as linen and lime. On athletes in the Roger Pro Fire also have the linen and lime colorway, and Iga Swiatek is embracing all things linen and lime as well.

Wilson Intrigue Tour

Marta Kostyuk

Wilson signed an entirely new crop of Tennis 360 athletes, players wearing Wilson head to toe while using the brand’s frames, but Marta Kostyuk remains the OG Wilson 360 athlete. Her Intrigue Tour for the Australian courts featured (past tense since she lost in the first round) a white base paired with deep red and bright red accenting, further showing how the Chicago-based brand is going all in on the signature brand color of red. This colorway spans the entire lineup of Wilson athletes playing in either a new Rush 5 Tour model or the Intrigue.

Nike GP Challenge 1.5 Osaka

Naomi Osaka

Really, the drama attached to Naomi Osaka’s look isn’t the shoes, but they do play a part. The jellyfish-inspired kit made waves during one of the final walk-out moments of the first round and included quite a bit of theatrics that weren’t part of the actual performance attire, but her on-court dress was still completely custom, including the GP Challenge sneakers made to match that included her “NO” logo on the tongue.

Asics is outfitting sponsored players in the fresh Melbourne Collection, highlighted by the new Solution Speed FF 4 in a white base with accents of light blue and pink. Belinda Bencic leads the Asics contingent on the court with an exclusive match jacquard dress, while Lorenzo Musetti is wearing an exclusive match jacquard short-sleeve shirt to pair with the Melbourne Collection sneaker colorways.

IMAGE COURTESY OF ASICS

Alex de Minaur may have bolted from Asics for Wilson for the Australian Open in a new Tennis 360 deal that includes shoes, but his footwear hasn’t quite caught up. The Australian is still wearing Asics shoes, just with the branding covered.

Aryna Sabalenka again went with the star treatment on her Nike footwear to match her custom dress. In a shoe that looks uncannily like what she wore at the 2025 US Open, Sabalenka’s Vapor 12 Premium has a white base with bright peach accents and silver starlike sparkles. There’s a tiger head on the tongue. It’s basically the same look she had in New York.

GETTY

K-Swiss isn’t letting off the gas when it comes to player-edition models. Ekaterina Alexandrova and Lyudmila Samsonova both get an Ultrashot 4 in white, lunar rock, and purple haze, special colorways just for them.

IMAGE COURTESY OF K-SWISS

Babolat recently launched the new Jet Mach 4, and we’ve seen Cam Norrie sporting the fresh release in both an all-red version and a white base with red accents.

Nike is embracing plenty of color in Melbourne this year, both in the apparel and on the footwear. But the star of show for AO footwear is neon yellow. Star players such as Carlos Alcaraz (Vapor 12), Amanda Anisimova (Vapor Pro 3), and Mirra Andreeva (GP Challenge 1.5) are all in bright yellow shoes, with each sporting Nike’s iconic late 80s “Aqua Gear” branding and embellishments.

IMAGES COURTESY OF NIKE

After going green last year, New Balance turns up to Melbourne embracing all things purple for players not named Coco Gauff. The popular FuelCell 996v6 and Fresh Foam X CT-Rally v2 both sport shades of purple.

Yonex athletes have a few colorways to choose from in the 2026 Melbourne Collection, even within the Eclipsion family of shoes. Athletes will be switching between a cream-based design with deep blue and a navy design with white and a blue-and-white-speckled outsole. As is typical, many of the Yonex players get their name and country flag added to the shoe’s upper.

IMAGE COURTESY OF YONEX

Mizuno has the all-new Wave Exceed Tour 7 in white and dazzling blue for the men and ice water and lightning yellow for the women. Players wearing the Wave Enforce Tour 2 have the same colorway combinations in the more robust design.

Daniil Medvedev is sporting all sorts of color and geometry on his Lacoste shirt, but that doesn’t leave much room for busyness elsewhere, as his player-edition AG-LT23 Ultra comes more subtle in his mix of white and yellow, but still with his gaming-inspired logo.

Madison Keys is still rocking pairs of the Nike Vapor X.

Adidas athletes have a range of shoes to choose from for Australia, led by the launching of the new Barricade. The orange-dominant color scheme in Melbourne from the German brand makes its way to footwear in a lucid orange, core black, pure orange combination available to players, although most athletes are still wearing an all-white version (Jessica Pegula, for example) or a white base with hints of orange, à la Alexander Zverev.

Daria Kasatkina, a Russian-turned-Australian pro, got a personal touch on her custom shoes from adidas, with her nickname and the Australian flag printed on the upper.

Leylah Fernandez was once one of the Shoe Report’s favorite athletes to watch, as the Lululemon athlete didn’t sign a shoe deal when she joined the Canadian apparel company. She’s worn everything from On to Puma basketball shoes to her dad’s unreleased brand but has seemingly settled in on K-Swiss, having been consistent with them since summer 2025 and now wearing a Hypercourt.

Follow Tim Newcomb’s tennis gear coverage on Instagram at Felt Alley Tennis.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP FOR THE TSS NEWSLETTER

Mixed Doubles

Sydney

Mixed Doubles

Mixed Doubles

Photography by Adrian Mesko

Originally Featured Volume 2 of OPEN Tennis — BUY

Sydney

Mixed Doubles

Mixed Doubles

Photography by Adrian Mesko

Originally Featured Volume 2 of OPEN Tennis — BUY

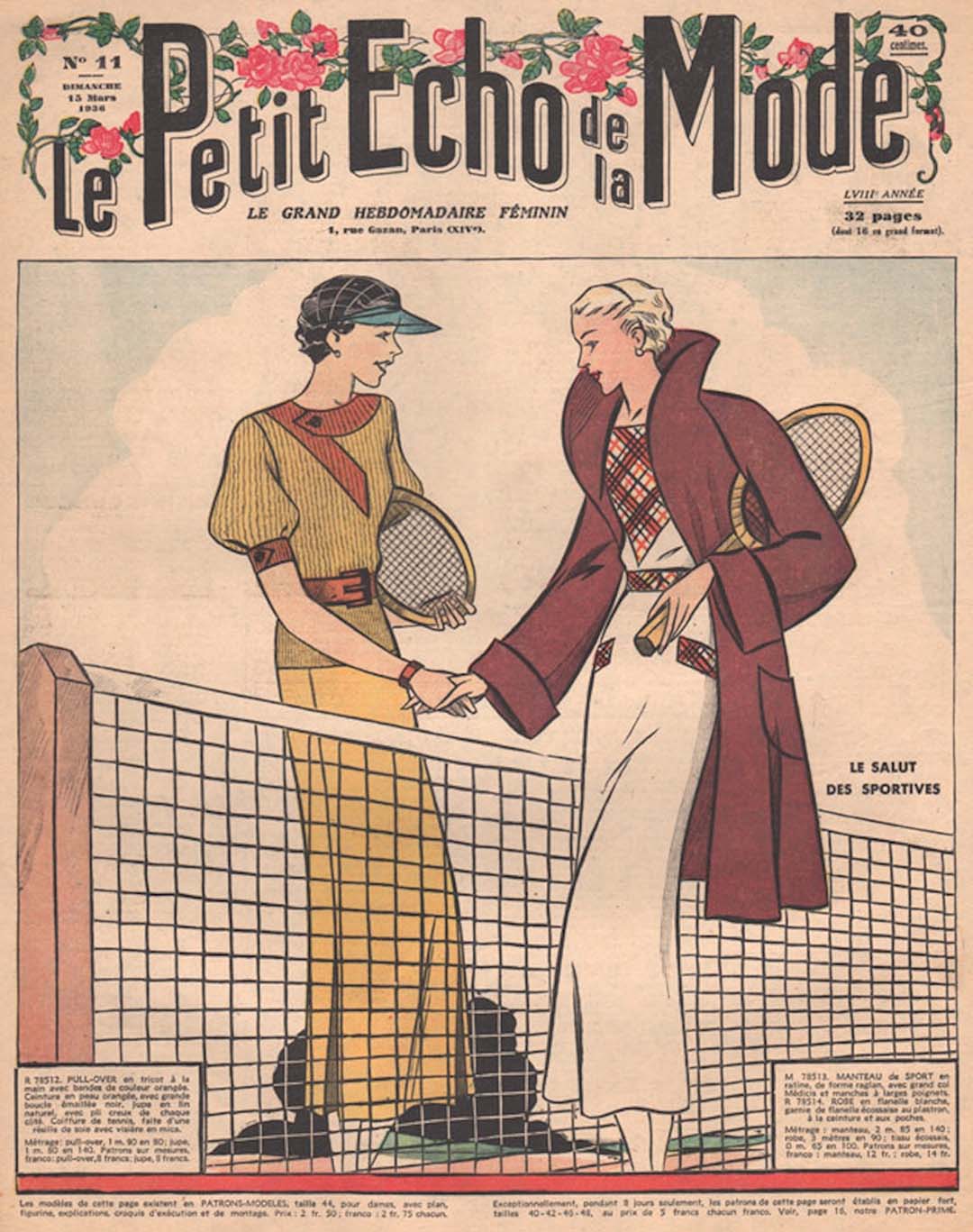

For the second edition of OPEN Tennis magazine, Adrian Mesko photographed models Franny Richardson, Serena Wardell, Torin Verdone & Patrick Kremmer in Tamarama, a beachside suburb of his native Sydney. Styled by Gemma Keil, the shoot captures the crew as they meet for an après beach hit and giggle. To see the whole shoot, pick up a copy of OPEN Tennis Vol. 2. And look out for the debonaire Mr. Mesko on the grounds of this year’s Australian Open.

TENNIS. ART. CULTURE. FASHION. TRAVEL. IDEAS. — SIGN UP

The Ghost Writers

The Ghost Writers

The Ghost Writers

Amazon’s got AI churning out tennis biographies by the dozen, but to what end?

Amazon’s got AI churning out tennis biographies by the dozen, but to what end?

By Simon Cambers

Illustration by Dalbert B. Vilarino

Featured in Volume 3 of OPEN Tennis — BUY

The Ghost Writers

The Ghost Writers

Amazon’s got AI churning out tennis biographies by the dozen, but to what end?

Amazon’s got AI churning out tennis biographies by the dozen, but to what end?

By Simon Cambers

Illustration by Dalbert B. VilarinoFeatured in Volume 3 of OPEN Tennis — BUY

Illustration by Dalbert B. Vilarino

Illustration by Dalbert B. Vilarino

Anyone who has ever written a book—be it on tennis, on other sports, or in fact on any subject—will know how difficult it is to make it a success. Unless you happen to have invented Harry Potter, it is incredibly hard to produce a bestseller. For the vast majority of authors, writing books is not a path to riches. And it is becoming even more difficult, thanks to AI.

Three years ago, I was lucky enough to have a book published. The Roger Federer Effect, cowritten with my friend and colleague Simon Graf, came out in October 2022. Timed somewhat fortuitously with Federer’s retirement, it was well received, with the German version selling well in Switzerland.

In the days and weeks after publication, I became somewhat addicted to checking the Amazon bestselling lists, a habit that has proved hard to shake off, even now. But those Amazon lists also serve a purpose: They’re the easiest way to get at least an idea about how your book is doing.

Type “Roger Federer biography” into a search on Amazon, and you’ll find a host of books about the 20-time Grand Slam winner. These include books by well-known writers like Rene Stauffer, Christopher Clarey, Chris Bowers, and even our own. However, there are also a number of books—ahead of ours in the list—all self-published, all with similarly laid-out covers, all slightly artificial-looking.

Wanting to know a little more, I clicked on one: Roger Federer biography: Mastering the Court: The Unstoppable Rise and Enduring Legacy of a Tennis Icon, by “Graham Newberry.” Not recognizing the author was a red flag in itself—the tennis world is a small one—while its cover was slightly disturbing, picturing someone resembling Federer, but wearing Asics shoes instead of Nike or On, and some random, rogue letters—“RIIS”—in the title on the cover. On further inspection, things became clearer. Newberry is a prolific “writer,” with several titles to his name. Impressive, right? Well, no. A closer look reveals that many of these books—covering the likes of Jack Nicklaus, Wayne Gretzky, and Lionel Messi—were published within days of one another. He even managed to write four biographies of former U.S. presidents on successive days.

Newberry is far from alone. Check out “Juan T. Parker,” “Sydney J. Prince,” and “George Clinton,” among many, many others. Clinton has written biographies of Jannik Sinner, Carlos Alcaraz, Novak Djokovic, Aryna Sabalenka, Iga Swiatek, Coco Gauff, Alexander Zverev, Elena Rybakina, Emma Raducanu, Naomi Osaka, Nick Kyrgios, Casper Ruud, Taylor Fritz, Frances Tiafoe, Anastasia Pavlyuchenkova, Madison Keys, Stefanos Tsitsipas, Belinda Bencic, and Olga Danilovic. None of these authors have a digital footprint outside of Amazon, and almost none of them have any reviews.

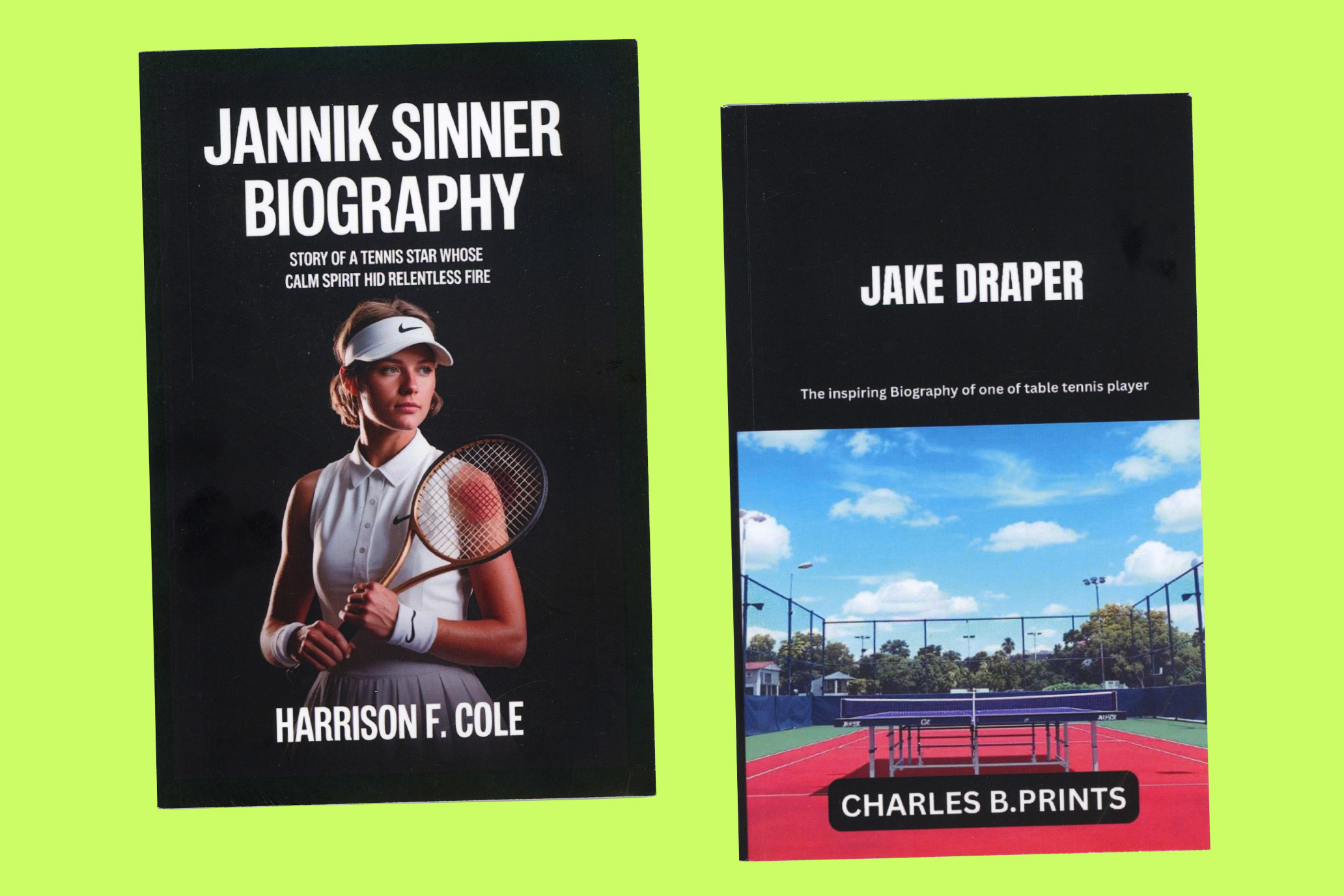

Some of these clearly AI-generated books are comical. Chapter 1 of Newberry’s Federer book is all about…Serena Williams. Ahem. Some are even laugh-out-loud, like the books by Charles B. Prints (or Charles A. Prints), which reimagine Petra Kvitova and Ons Jabeur—and Jake [sic] Draper—as famous table tennis stars, but use all their tennis and life backstories to do so.

Some books are downright weird, like Harrison F. Cole’s biography of Carlos Alcaraz, the cover of which is definitely not a photo of Alcaraz; it’s no tennis player I’ve ever seen and looks vaguely like an actor or a singer in a boy band, wearing a collared, sleeveless top. His biography of Jannik Sinner carries a cover photo that does not even try to make it look like the Italian, instead showing a woman.

Many of these books pop up in the days after a big event. When Coco Gauff won the French Open in June, a number of suspicious titles appeared. Sabrina M. Ellsworth managed to publish an Aryna Sabalenka biography in September, two days after she penned one on Jasmine Paolini.

AI has made all this possible, allowing factories (or individuals) to produce books en masse. Writing in the New Yorker in October, Stephen Witt reported that there are thought to be almost 4 hundred trillion words on the indexed internet,” but many of them are useless—high quality text is rare, and the supply is finite. “Since A.I. chatbots are recycling existing work, they rely on cliché, and their phrasing grows stale quickly. It’s difficult to get fresh, high quality writing out of theme—I have tried,” Witt wrote.

But perhaps a bigger problem than lousy prose is the lack of regulation. Amazon is more than happy to allow these books to flood the market, pushing legitimate titles down its search engine. Some of these books are even sponsored.

Recent "works" by Harrison F. Cole and Charles B. Prints.

Recent "works" by Harrison F. Cole and Charles B. Prints.

In theory, if a book is entirely AI-generated and published via the Kindle platform, the author must tell Amazon. However, Amazon doesn’t pass on that knowledge to buyers. If it’s “AI-assisted,” then the author can keep quiet. It took them until late 2023 to bring in a rule restricting authors to the number of books they can self-publish on a given day, to three. It took me 18 months to cowrite one book.

“If you make a keyword search for a particular topic or even an author, you have to wade through several pages of often irrelevant results,” said George Walkley, a U.K.-based expert in AI and publishing. “I think that’s probably the biggest short-term impact for publishers, that it may deter people from finding the book that they were looking for.”

Walkley says the low production costs mean authors of AI books have to sell only a few to make a profit. “I think that really points to what the long game is,” he said. “It’s a volume play. They only need to sell a few copies, whereas you or I would have to be looking to hundreds or thousands of sales of a book in order to earn back the investment we made in it, in terms of time.”

Walkley agrees Amazon should do more to regulate but doesn’t think they should promote traditionally published books above self-published ones, because not everyone has the luxury of finding a publisher. “Amazon can attempt to use software to detect what is AI-written and what is written by human beings. But again, this isn’t 100 percent reliable. I think Amazon has a real challenge here in trying to keep an open publishing ecosystem in an era where AI is available.”

There’s another danger, thanks to AI: plagiarism. During my research, I found another book on Federer, the sample of which revealed that it was almost identical to The Master, by Christopher Clarey. The author—“Shelly Phomsouvandara”—had also written a book on the former boxer Ed Latimore, which turned out to be stolen from Latimore’s autobiography. I contacted both Clarey and Latimore, and, with the help of their publishers, the books were removed.

Clarey says Amazon needs to do more. “It just seems so easy in the age of AI to be able to do these things,” he said. “I think it’s on Amazon and the people who are providing the links to the sales to at least do all they can to avoid this being put up online, maybe raise the bar in terms of how hard it is to get a book on there. Amazon responded to my initial request to explain the guidelines, wanting to know my deadline, but then didn’t get back to me.

“The bigger question for me, really, is the AI aspect of it, and what happens to sports book authors and book authors going forward. Because it’s just so easy to produce a work, probably, of decent quality with very, very little effort by aggregating all the known published thought on a particular figure.”

AI can’t go out and talk to people and can’t witness events, which gives journalists an edge. But when it comes to historical books, it is improving all the time. Nevertheless, even in the tennis titles I’ve seen, there is not a single example of quoted speech. No information is ever attributed to anyone, and no notes on sources or indices are forthcoming.

“I certainly don’t think it can be done as well as a top biographer, or somebody who’s really spent, like I did, two years on a book about [Rafael] Nadal [The Warrior], using all kinds of new reporting and my old references, my old material, and my perspective over those many years. But certainly, somebody can produce something that’s able to compete with something that I put a huge amount of sweat and effort into, very quickly. So that’s really the challenge: how it dilutes the market, floods the market, and makes it thrive.”

Given all that, it’s remarkable to see that these “books” have the temerity to include a disclaimer discouraging anyone, for reasons that are something of a mystery, from reproducing any of their content without permission.

TENNIS. ART. CULTURE. FASHION. TRAVEL. IDEAS. — SIGN UP

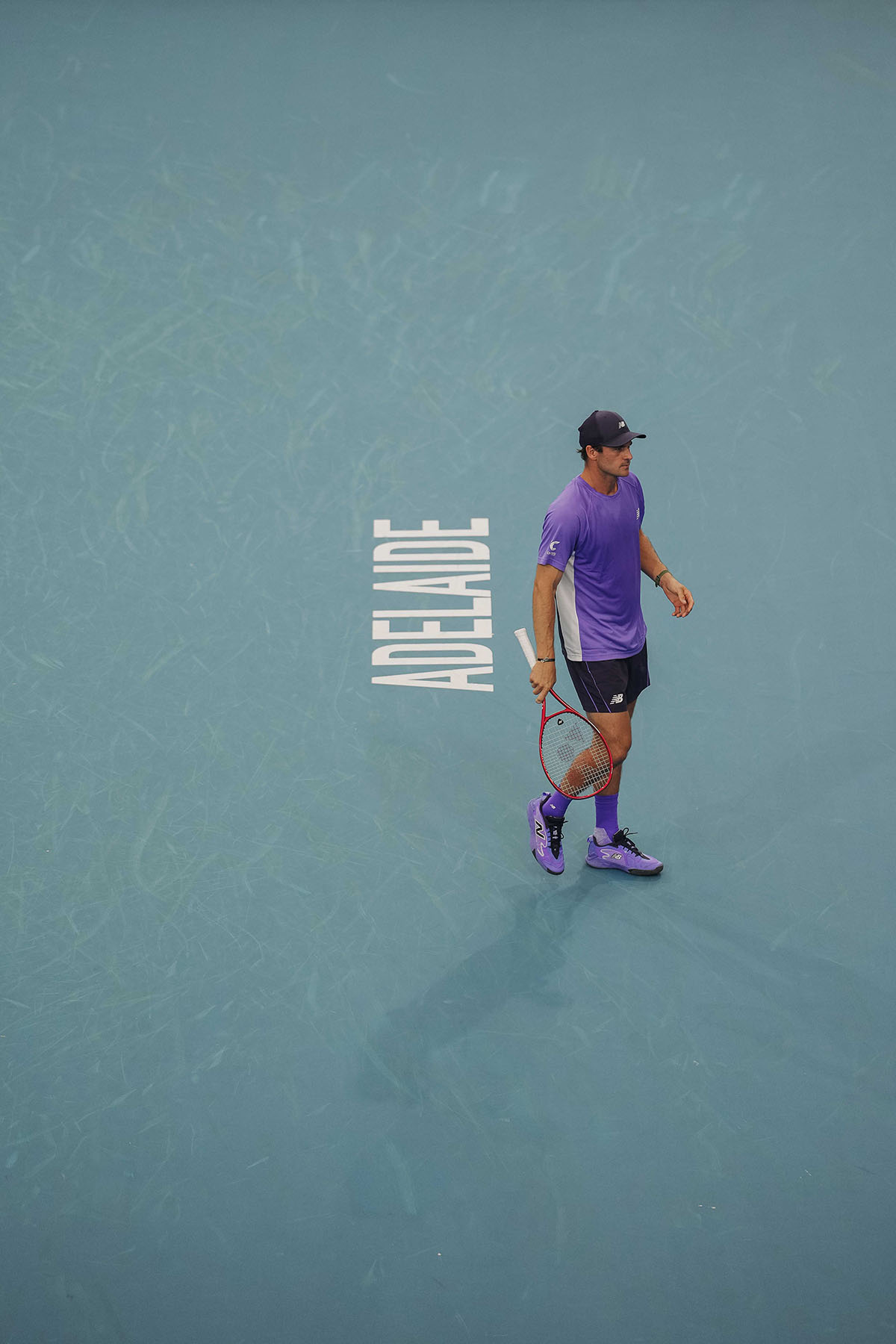

Postcard from Adelaide '26

Postcard from Adelaide

Postcard from Adelaide

Photographer Stuart Kerr kicks off the Australian season with another dispatch from the Adelaide International Open.

Photographer Stuart Kerr kicks off the Australian season with another dispatch from the Adelaide International Open.

By Stuart Kerr

January 16, 2026

YOUR WEEK IN TENNIS — SIGN UP FOR THE SECOND SERVE NEWSLETTER

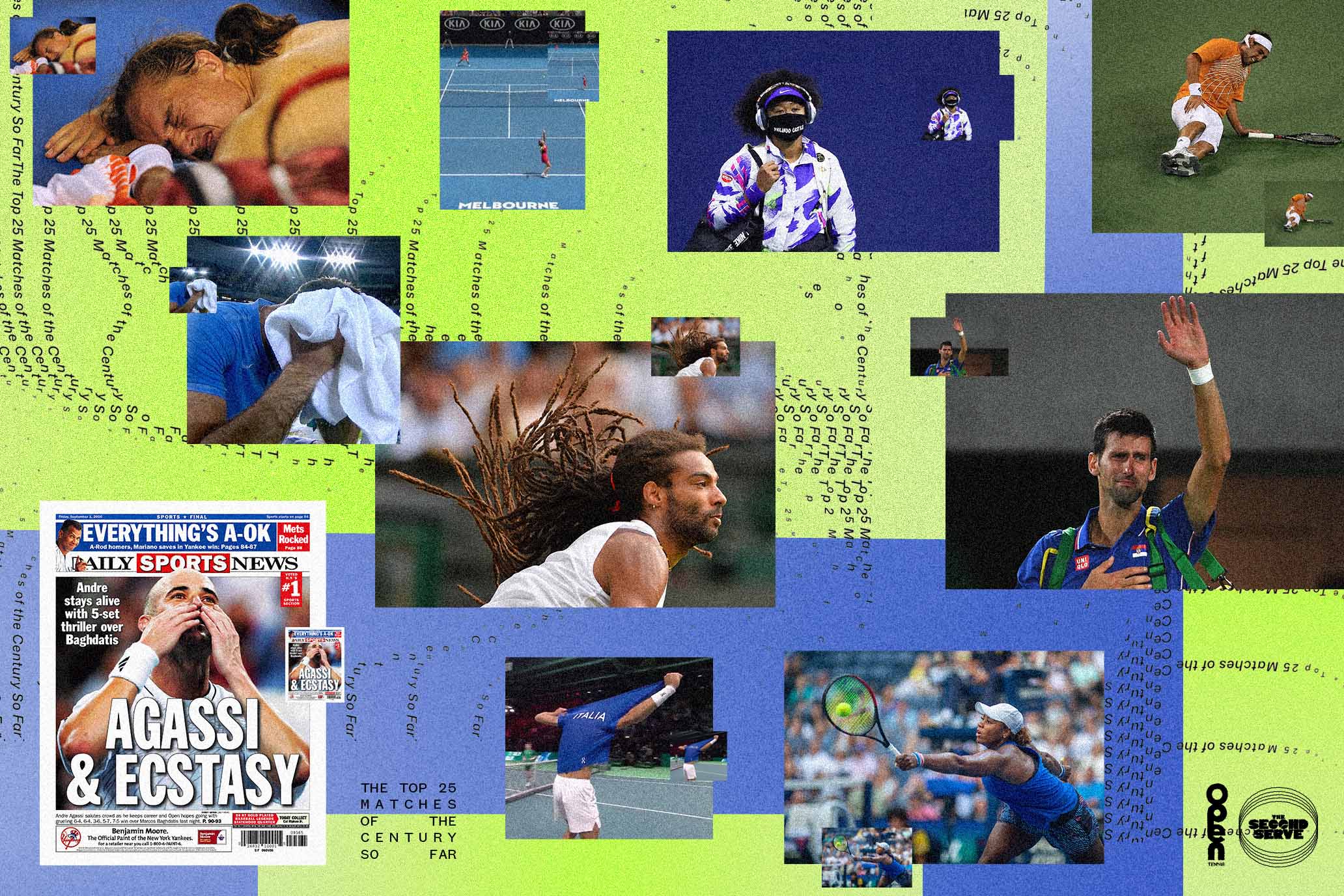

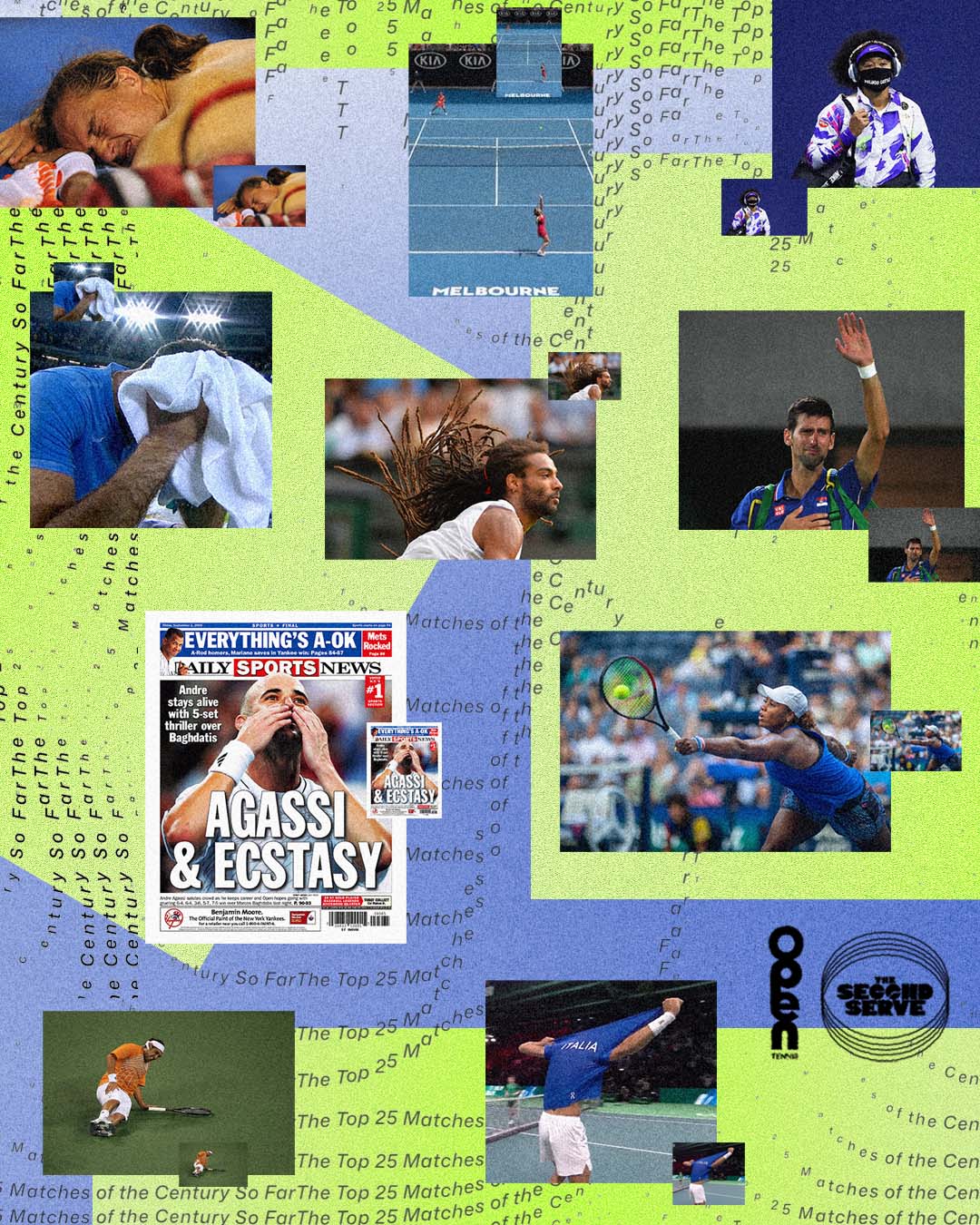

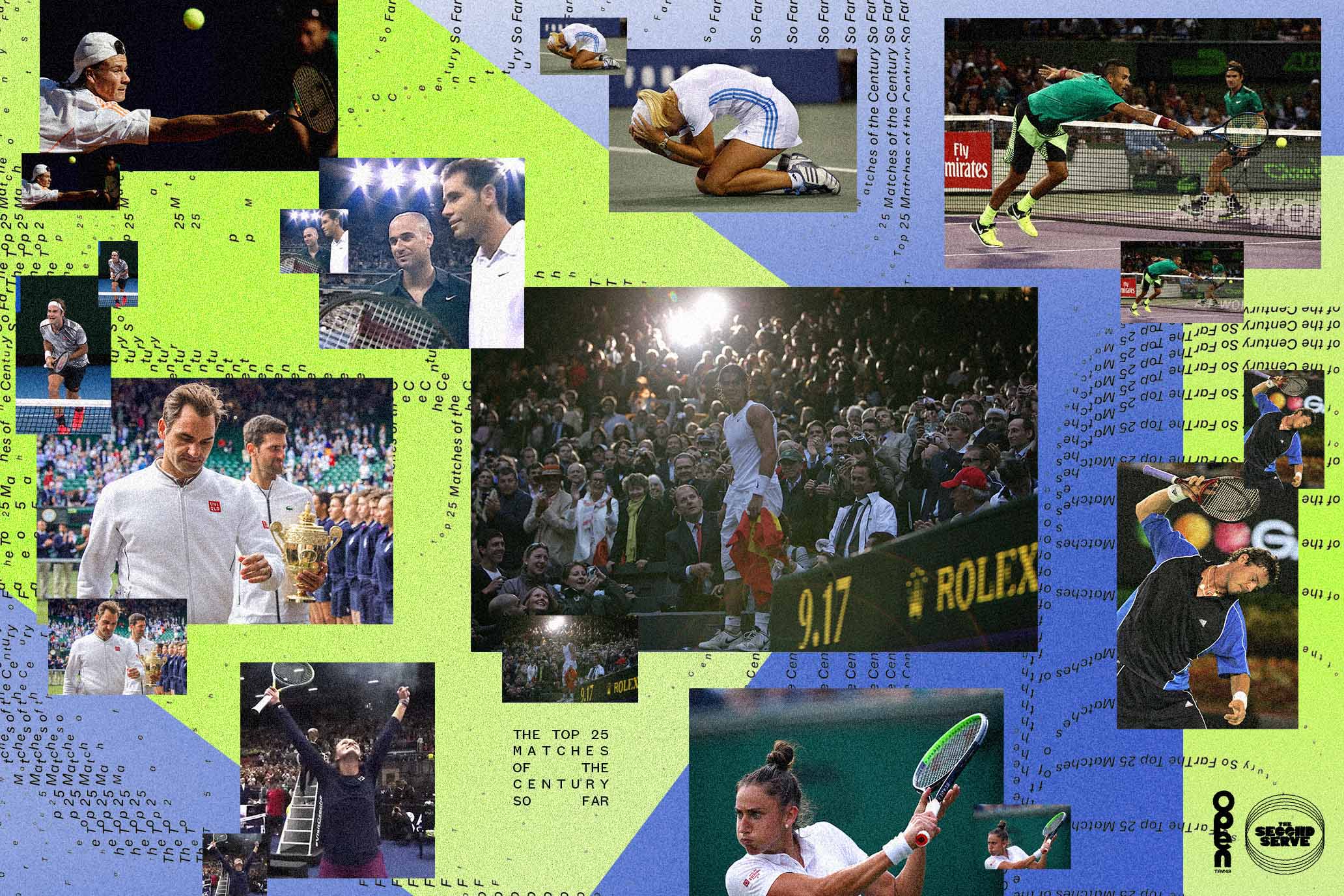

The Top 25 Matches of the Century So Far

The Top 25 Matches of the Century So Far

The Top 25 Matches of the Century So Far

Our favorites for performance, lifestyle, and everything in between.

Our favorites for performance, lifestyle, and everything in between.

By The Second Serve

December 26, 2025

Since we’re a quarter of the way through the century, we thought it a good time to take a look back at all the great tennis that has transpired since the turn of the millennium. We’ve asked some of the best tennis writers working today to choose what they thought were the best matches of the past quarter century, and to help us rank them based on some combination of the level of play, the moment, the stage, and the historical implications. The results were often surprising, always fun—we’re sure you won’t find anything controversial herein.

25.

2025 Davis Cup, Cobolli d. Bergs, 6–3, 6–7, 7–6

Davis Cup—in many ways a vestige of the pre–Open Era that never successfully adapted to the commercialization of tennis—has had a rough go in the 21st century so far, losing the reliable participation of top players and other elements of its magic formula. But for one night in November 2025, even the stripped mine bore a gold rush of a match, with 43rd-ranked Zizou Bergs of Belgium and 22nd-ranked Flavio Cobolli each playing their breathless best as the match went beyond any conceivable last gasp.

Yanking momentum back and forth, the pair combined to save a baker’s dozen match points between them before Cobolli bombed a serve up the T that Bergs could not wrangle back into the court on the 14th, the culmination of an epic third-set tiebreak. The crowd in Bologna roared for Cobolli—only the third-best Italian man but the top Italian who showed up for the occasion—and a couple days later he’d win Italy its third straight Davis Cup title.

Bergs, a player initially known more for a coquettish TikTok presence than his tennis, may never get closer to glory than that, but just being part of such a moment also might be enough. “You gave everything, and that is the greatest victory of all,” his father, Koen Bergs, wrote to Zizou later. “No matter the score, you have already won in my eyes. You are a champion of spirit, a warrior of heart, and a son who makes his father endlessly proud.” —Ben Rothenberg

24.

2012 Australian Open, 2nd Round, Tomic d. Dolgopolov, 6–4, 3–6, 6–3, 6–7, 6–3

By the 2010s, men’s tennis had steadily grown more and more monotonously metronomic. Two dudes, planted behind the baseline, lashing topspin ground strokes at each other until one of them blinked. The 2012 Australian Open ended with the farcical peak of this when Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic needed nearly six hours of baseline grinding to finally determine a winner. But a week prior, in that same Rod Laver Arena in Melbourne, two oddballs had shown what was possible. Alexandr Dolgopolov and Bernard Tomic put on as outré an exhibition as men’s tennis has ever seen this century, matching each other’s freak with exchanges of exaggerated slices.

Their creative carving sculpted something beautiful that would never again get such a stage in men’s tennis this century. That this match went five sets was entirely incidental to its greatness; viewers were hooked early in the first set. Forget metronomic—did you ever see those pictures of the sorts of webs spiders weave after being given LSD? That was this match.

Tomic, who was then a genuine hope for his country as a 19-year-old fresh off a Cinderella quarterfinal run at Wimbledon, won to reach the fourth round; he would top out there and never made it to another major quarterfinal in his career. A couple of years later Tomic would play almost certainly the worst match of the century when he lost to Jarkko Nieminen in just 28 minutes. But on that one night, with a continental grip, Tomic brushed up against the truly sublime. —Ben Rothenberg

23.

2019 US Open, 2nd Round, Townsend d. Halep, 2–6, 6–3, 7–6

Taylor Townsend had never beaten a top 10 player, progressed past the second round of the US Open, or taken a set off of former No.1 Simona Halep when she lined up against the reigning Wimbledon champion at Arthur Ashe Stadium in 2019. Then ranked No. 116, Townsend barely scraped through qualifying to earn her spot in the main draw. To earn the biggest win of her career, Townsend engineered the century’s most audacious display of net-rushing tennis, a style that had all but disappeared after the 1990s. “I think it was really great confirmation that this style of play works,” Townsend said afterward, “that I can continue to do it.”

To disrupt Halep’s baseline rhythm and keep the counterpunching Romanian on her heels, Townsend crashed the net an astounding 106 times. Her intentions were laid bare in the opening game, as she held serve off four successful forays into the net. Halep ran off five straight games to take the first set, but Townsend never backed off. She continued to chip and charge and serve and volley to finally take her first set in eight tries against Halep, setting up a dramatic final set. Townsend crashed the net 64 times in the third set, forcing Halep to respond in kind with her own baseline magic.

By the time Halep had saved two match points and Townsend saved one, the only mystery left was the result. The entire stadium, which included Kobe Bryant and Nadia Comaneci, knew what was coming in the final tiebreak: Taylor would rush the net, and Simona would either find the pass or not. It was edge-of-the-seat viewing, and as the old cliché goes, fortune favored the brave. —Courtney Nguyen

22.

2016 Olympics, 1st Round, Del Potro d. Djokovic, 7–6, 7–6

Going into the match, Novak Djokovic was at the height of his powers; the only accolade that had eluded him thus far was an Olympic gold, and thus joining Rafa and Andre as the only men to complete the career “Golden Slam” (though Steffi Graf had done it in a calendar year). He’d leave the Olympic stadium bereft, though. So far Novak had been in uncharacteristically lackluster form at the Olympics, but this year was supposed to be different, with Novak seemingly able to do anything on a tennis court. What we didn’t know at the time was that Novak was at the beginning of his yearlong lost weekend, where he’d miss time due to injury and see his ranking drop to the un-Novakian number of 12 and his love life written about in the tabloids. There was no evidence of any of that in Rio, though.

Juan Martin del Potro, on the other hand, showed up greatly diminished from the heady days of 2009 when he upset Federer in the US Open final. The atmosphere in Rio was electric from the start, practically a home court for the Argentine del Potro, and what ensued was a deeply emotional match that would see both players—and seemingly the whole stadium—in tears. While del Potro’s backhand was barely effective due to the wrist injuries that would end his career early, his forehand was a problem. Novak tried to stay away from it, but when del Potro got a look, he seemed to demolish the ball. He used that shot to pummel most of his 41 clean winners over just two tight sets. That, along with an 86 percent first-serve percentage, was too much for Novak, whose heart was broken again. Novak would get his Golden Slam eight years later in Paris, and del Potro would win silver at the games and eventually lift the trophy two years later in Miami, but Rio was the signature late-career triumph for del Potro, and he knew it. “I wanted to win, but I also wanted the match to go on because everything was wonderful,” he said afterward. It was an unexpectedly epic and moving run for del Potro, who had the Brazilian crowd in the palm of his hand. —David Bartholow

21.

2020 US Open Semifinal, Osaka d. Brady, 7–6, 3–6, 6–3

Many elements of the 2020 US Open, played behind closed doors as the pandemic roiled onward outside, felt understandably depressing. Arthur Ashe Stadium, known for its buzz and roars that reach the rafters, had become an empty cavern whose size only amplified the echoing emptiness.

Though there were fewer than 150 people in attendance in a stadium built for more than 22,000, the women’s semifinals of that tournament turned the void into infinite possibility. Under the roof, Naomi Osaka and Jennifer Brady distilled something that felt lab-perfect in the pristine conditions: pure power tennis in a vacuum.

The two women combined for 19 aces and just three double faults, belting baseline winners on command in a dazzling barrage of reverberating power tennis. No one had shaken off the pandemic dust as quickly as Brady, who had won in a stacked field in Lexington before coming to New York ready to take on the world. She played the match of her life, but Osaka was just better—as she so often proves to be across her absurd 13–1 record in the quarterfinals, semifinals, and finals of majors.

Osaka, who had won the loudest and most chaotic US Open final a couple years earlier, thrived in the opposite extreme and won her third major a couple days later. But the real victory, she said, was making the final: By playing seven matches, Osaka ensured she would get to wear all seven of the masks bearing names of victims of racialized violence that she had made for the tournament, which she said had been “a very big motivating factor” for her.

Osaka won a rematch over Brady a few months later in the final of the 2021 Australian Open. That one didn’t live up to the high-proof potency of this match; it’s hard to imagine the conditions will ever exist again for the recipe they brewed the first time. —Ben Rothenberg

20.

2018 Australian Open, 3rd Round, Halep d. Davis, 4–6, 6–4, 15–13

After twin towers John Isner and Kevin Anderson needed more than six and a half hours to end their deadlocked 2018 Wimbledon semifinals with a 24–22 fifth set, the rules of tennis were rewritten. Soon, no match, anywhere in professional tennis, would be allowed to continue on past 7–6 in the final set. The rule was made to stop mundane marathons between men who can’t return serve, but tennis has never been one-size-fits-all, and a lot of classics were surely prevented in the process.

Thankfully, though, Simona Halep and Lauren Davis had already played one last classic a few months earlier. In a lightweight throwdown for the ages, the generously listed 5-foot-6 Halep and 5-foot-2 Davis tussled back and forth for hours. With neither possessing a serve that could win her many free points, every game was a complete toss-up. Even in the tightest moments, the two stayed attacking throughout, trading winners and breaks as the third-set score pendulated into double digits.

Davis had three match points on return at 10–11 but couldn’t convert, for a good reason: One of her toenails was falling off. Though ranked No. 1, Halep had a lot to prove: She was playing in Melbourne without an apparel sponsor, wearing a red dress she’d ordered from China and an Australian Open-branded visor.

Halep would make it all the way to the finals of that Australian Open, winning another marathon in the semifinals against Angelique Kerber before finally hitting the wall in the final against Caroline Wozniacki. Halep, who had to be hospitalized for dehydration after losing that final, would finally win an elusive first major title a few months later in Paris. But the best match of her year—and the grittiest of her career—was against Davis. —Ben Rothenberg

19.

2015 Wimbledon, 2nd Round, Brown d. Nadal 7–5, 3–6, 6–4, 6–4

What if low-percentage suddenly became high-percentage tennis? For the answer, look no further than Dustin Brown’s epic upset of Rafael Nadal at Wimbledon. Rafa came into the tournament somewhat diminished as a 10 seed after an appendectomy in late 2014, but the match was less about Nadal than Brown, whose brand of tennis was at one point described by commentator Andrew Castle as “hilarious.”

Brown, 30, came into the match ranked 102 in the world, having come through qualifying. Though a prototypical journeyman, Brown was a grass-court specialist and thrilling shotmaker who’d beaten Lleyton Hewitt at the Championships two years prior and had smoked Rafa on the grass of Halle the previous year—and he put on a hell of a show. Rafa lost this match after the very first game, won by Brown in four quick points: a serve + drop shot, a serve + swinging backhand volley winner, a 123 mph second-serve ace, and a drop volley. The ensuing four sets were characterized by more of the same. Every time Rafa held serve, it felt like a dodged bullet, whereas Brown held easily. By the sixth game the broadcast team, who had given Brown so little of a chance they didn’t bother to familiarize themselves with his bio, was wondering if Nadal was washed-up (He wasn’t). On set point in the third, in an attempt to return a Brown serve up the T, Nadal instead hit his own shin with his racquet, sending a bloodcurdling crack throughout Centre Court. Never has Nadal looked so out of sorts.

The match calls to mind the infamous “No Mas” fight, during which the more powerful Roberto Duran was so fatally flummoxed by Ray Leonard’s audacious style, he basically shut down. It’s nearly as notorious. In the recent history of Jamaican sports, there are only the achievements of Jamaican sprinters (Usain Bolt chief among them) and Brown’s takedown of Nadal. Here was a guy whom the elites in the Jamaican tennis establishment didn’t want—he represented Germany at the time but had the full support of the Jamaican street—a former ball boy at a Montego Bay resort, deploying a flashy, risky, and joyous brand of tennis to prevail on his sport’s biggest stage, against one of its most august opponents. —David Shaftel

18.

2006 US Open, 2nd Round, Agassi d. Baghdatis, 6–4, 6–4, 3–6, 5–7, 7–5

Take two of the best pure ball-strikers alive, one at the end of his career and the other at the start. Beat them to such a pulp that they can barely walk, and have them play a fifth set. This is your recipe for an unforgettable tennis match—or at least it was in the second round of the 2006 US Open, where a 36-year-old Andre Agassi met a 21-year-old Marcos Baghdatis. Maybe it was the contrarian in me, but despite Agassi’s legend, I recall rooting for the Cypriot, who had just broken into the top 10 that season. A paunchy shotmaker in board shorts and a headband, he seemed to possess the gift of perfect timing that defined Agassi’s own game. My friends and I liked to imitate the Baghdatis running forehand, badly.

That night, Agassi took the first two sets, then Baghdatis the next two. By the time they arrived in the final frame, pain had emerged as the third character in the match. Baghdatis was hopping around, rolling on the ground in cramp agony. Agassi, pumped full of cortisone injections to grit through his final tournament, saw his naturally stiff pigeon-toed walk get even creakier still. Between points it looked like neither man could walk 10 paces in a straight line. But during the points they hurtled around Ashe in crisp and hypnotic baseline rallies, their contact as clean as their faces were ragged. Agassi notched the last victory of his career; Baghdatis would never again touch the heights of that season. From them I learned how tennis could ravage a body, both over the course of an epic career, and over the course of a single evening. In his memoir Agassi wrote that the two players, flat on their backs and receiving treatment after the match, held hands—happy to have shown the world all that, and to have survived. —Giri Nathan

17.

2019 Indian Wells Final, Andreescu d. Kerber, 6–4, 3–6, 6–4

I remember the rage that propelled Bianca Andreescu to winning that Indian Wells 2019 final against Angelique Kerber, whose lefty paw had already won three majors. Ranked 152 to start 2019, 60 ahead of Indian Wells and 24 after, the 18-year-old became the fourth-youngest player to win a WTA 1000 at the time (Hingis, Seles, S. Williams), the youngest here since Serena (1999), and the first wild card in the event’s history.

I was on-site when she blasted through like a joyful hurricane, and what got her the title against Kerber, who tried everything to escape that kid, was her unique recipe of power and variety, added to an exceptional tennis IQ, a forehand hitting like a whip, and will power as X factor: She’d yell her “Come on!!!” and the ground would shake.

Yet, down a break in the third, Andreescu was about to lose her fairy-tale ending, her right shoulder in pain. But then it happened. She called coach Sylvain Bruneau and sat there repeating how badly she wanted to win, tears in her eyes, with an intensity that went through the stadium like a wildfire. And so Bibi went back and took over, missed three match points at 5–3 but hit a monster forehand at 5–4, 30A. “She’s gonna do it. It’s insane,” was my only thought. A great return later, and she was yelling out of rage and pride on the ground, everybody pinching themselves.

The rest is history: a 10-win streak until retirement in Miami; just two matches played before winning the WTA 1000 in Toronto and the US Open, beating Serena Williams. She was top five, and the world was her oyster when her left knee gave up at the WTA Finals, starting a streak of injury issues. We’re still here, waiting for Bibi, just because we know how unreal her peak is. —Carole Bouchard

16.

2001 Wimbledon Final, Ivanisevic d. Rafter, 6–3, 3–6, 6–3, 2–6, 9–7

Glorious chaos, in tennis form. One of the all-time great Wimbledon finals, even if the quality of the tennis itself was at times, as Pat Rafter admits, “pretty scratchy.” But this was about more than just tennis. Scarred by losing three finals and bruised by a shoulder injury, Goran Ivanisevic was ranked 125 and needed a wild card just to get in the event. Somehow his game came together, his serve began to fire, and the unthinkable became possible. Rafter, a serve and volleyer in the true Aussie tradition, had lost in the final the previous year, but after beating Andre Agassi in the semis, he was the favorite.

The final was pushed back to Monday due to rain, and tickets were sold on the gate for £40, a bargain that created an atmosphere more like a football match, with the Australians in green and gold mingling with Croatians in red and white checks, alongside Jack Nicholson, shades and all.

The match itself was chaos. Twice, Ivanisevic led by a set, but Rafter sped through the fourth to level. The fifth was nip and tuck until Ivanisevic fired a forehand return across Rafter to get the break for 8–7. Ivanisevic was so nervous he could hardly stand up, and that final game, wow. Three double faults, two on match point, and a third match point lost to perhaps the best backhand topspin lob of all time from Rafter before the Aussie returned into the net to finally give Ivanisevic his dream victory. —Simon Cambers

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP FOR THE TSS NEWSLETTER

The Top 25 Matches of the Century So Far — 15 - 6

15.

2021 Wimbledon, 2nd Round, Kerber d. Sorribes Tormo, 7–5, 5–7, 6–4

Angelique Kerber’s the queen of angles and timing, Sara Sorribes Tormo is all topspin and stamina, but they share a rare ability to generate classic matches. Their lack of innate power forces them to win points through colorful, inventive means that rub off on opponents and produce ecstatic slogs. It’s a shame they’ve only played each other this one time, and a tragedy that the only public video record of it is Wimbledon’s pathetic three-minute offering on YouTube.

Good thing I could never forget watching it on TV at the time. I’ve never seen a match with so many wonderful rallies—in three long sets on grass, still bright and fast in the first week, these two mustered only 19 combined unreturned serves. Rallies began on even terms and were free to flow to places that most modern tennis matches are too power-dominated to ever visit. This style can produce slower and more masochistic rallies than some are used to, but I think it captures the best of tennis. Such rallies showcase the broadest possible variety of shots on offense and defense, allowing the sport to shine both athletically and aesthetically, and for more than a moment at a time. SST broke serve early in the third set with a lob she hit while running backwards, at the end of an exchange that had already featured a baseline rally, an overhead, and a volley. I’ll take that over serve-plus-one, please and thank you. The match’s conclusion felt inevitable, as in so many Sorribes Tormo marathons: Her nonexistent serve eventually results in a love break at the worst possible time. Even in defeat, her persistence against a better player made her primarily responsible for the best match of the tournament, and the year. —Owen Lewis

14.

2008 Wimbledon Final, Nadal d. Federer, 6–4, 6–4, 6–7, 6–7, 9–7

The ultimate clash of styles, on the biggest stage, for the greatest prize of them all. Federer was trying to win for a record sixth straight time, while Nadal, the clay-court king, was the upstart looking to cause a big shock and prove that he could play on grass.

The anticipation was off the charts; Federer was unbeatable in his “back garden,” but Nadal had made the final in each of the two previous years, and if the fans didn’t know he was ready, Federer did, having been crushed by the Spaniard just a few weeks beforehand in the French Open final.

The match started late because of rain, and when it did begin, Federer was nervous. Nadal took the first two sets and was the better player early in the third, only for an 80-minute rain delay to turn the momentum in Federer’s favor. After grabbing the third set on the tiebreak, Federer saved two match points in the fourth, one with a brilliant backhand pass down the line, to take it to a decider.

The fifth set was again interrupted by rain, and when they resumed, the light was fading fast and it was almost impossible to see, with only TV making it look playable. Federer had the momentum and was serving first, but Nadal was unstoppable, finally breaking serve in the 15th game before serving it out for the biggest title of his life. Federer looked like a broken man. —Simon Cambers

13.

2005 Italian Open Final, Nadal d. Coria 1, 6–4, 3–6, 6–3, 4–6, 7–6

Nadal looked cooked. After three sets of clay-court trench warfare with a far more seasoned opponent, Rafa faltered, losing the fourth and falling down a double break in the decider. The break-back point he held at 0–3 felt like a small diversion before Guillermo Coria’s inevitable victory. Nadal, 18 years old at the time, disagreed: He played a patient, mature rally befitting of a much older player, ending with a perfectly timed forehand drop shot. (Show that point to anybody who thinks Alcaraz was the first Spaniard to use the dropper.) He then raised a thickly muscled left arm, leaped in the air, and roared.

What was powering this kid? Suddenly he had renewed energy, covering the court just as relentlessly as he had early on. If Carlos Alcaraz decided to play like Lorenzo Musetti, you’d get something like young Nadal here. Coria seemed to age trying to get the ball past this misplaced track star, even as he played brilliant tennis of his own. One desperate Coria get, off a screaming Nadal forehand down the line, turned into a perfect drop shot. They collided in a tiebreak, where, in classic Rafa fashion, Nadal finished the match the hard way. After missing a second-serve return on one championship point and double-faulting away another, Rafa chased down a variety of Coria rockets, including an overhead, eventually forcing an error with a vicious forehand pass. Nadal then fell to the ground in ecstasy, reacquainting Coria, best known these days for blowing a humongous lead in the 2004 Roland-Garros final, with how it feels to lose after expending every effort your body could offer up. Coria lost in the first round of the tournament in 2006. Nadal reached the final, played a similar epic against Roger Federer, and won that, too. —Owen Lewis

12.

2003 US Open Semifinal, Henin d. Capriati, 4–6, 7–5, 7–6

The ’03 US Open had been halted frequently by rain, to the point where this intriguing semi between Justine Henin and Jennifer Capriati commenced past 9 p.m.

In June, at Roland-Garros, Henin had won her first major singles title. Following 10 years as a teen prodigy and burnout case, Capriati in 2001 and 2002 had snapped up three Grand Slam singles titles. Each now hoped to reach the US Open final for the first time.

Added to the mix was a pleasing style contrast between Capriati’s forceful ground strokes and Henin’s rainbowlike palette of speeds, spins, and an extraordinary one-handed backhand.

For three hours and three minutes, these two lit up Ashe Stadium. Channeling the energy of the American crowd, Capriati came two points away from winning the match a staggering 11 times and served for it in each of the last two sets. But Henin was that rare mix of artist and warrior, repeatedly able to transition from defense to offense—and eventually, at 12:27 a.m. Saturday morning, she won in a third-set tiebreaker. Later that same Saturday, she would defeat compatriot Kim Clijsters in the finals. Four years later, she’d win a second US Open title.

This loss marked the second time Capriati had been beaten in the semis of the US Open in a third-set tiebreaker. Twelve years earlier, she’d lost that way vs. Monica Seles. And one year following the Henin match, more heartbreak in the semis, Capriati beaten in a third-set tiebreaker by Elena Dementieva. —Joel Drucker

11.

2022 Ostrava AGEL Open, Krejcikova d. Swiatek, 5–7, 7–6, 6–3

The 2022 final in Ostrava was three hours and 16 minutes of women’s tennis played at the height of its modern form. That’s what it took for Barbora Krejcikova to hand world No. 1 Iga Swiatek her first loss in a final in more than three years.

At her best, Krejcikova’s flat pace and depth were the perfect foil for Swiatek’s topspin-driven game. On paper, this had all the markings of an intriguing clash. But great matches are not solely defined by quality of play, dramatics, or significance. The truly memorable ones have a certain X factor, some magical alchemy that makes you feel you’re catching lightning in a bottle. In Ostrava, that X factor was…well…Ostrava!!! (Exclamation points courtesy of the tournament’s own campy branding.) A match between Poland’s brightest young sporting star and the Czech Republic’s newest major champion, played on the border of the two neighboring nations, meant a packed-out atmosphere that felt more like a Davis Cup final than a WTA 500 in autumn.

Swiatek and Krejcikova proceeded to reward the passionate fans with an absolute clinic, with Swiatek hitting 42 winners to 30 unforced errors and Krejcikova responding with 44 winners and 41 unforced errors. After holding off Krejcikova in a 73-minute first set, the Pole was two points from a straight-set win. But Krejcikova kept her cool to edge the tiebreak and broke Swiatek to earn a chance to serve out the win. The match ended in a rousing finale, with Swiatek dramatically saving five match points before Krejcikova fired an ace to win. —Courtney Nguyen

10.

2005 Australian Open Semifinal, Safin d. Federer, 5–7, 6–4, 5–7, 7–6, 9–7

Marat Safin is on the very short list of players who have upstaged Roger Federer’s genius. This masterpiece of a semifinal at the Australian Open 2005 against Federer, the revenge of the 2004 final, is his legacy, ahead of his US Open final perfection against Pete Sampras. On that day, Safin, the temperamental artist who reached world No. 1 at 20 in 2000, the youngest of the Open Era at the time, reached a state of grace.

This semifinal against Federer had it all: out-of-this-world quality and variety of play, cast, stakes, twists, and turns. You couldn’t look away. So here I was, waking up the building in the middle of the night in Paris while yelling, “You’ve got to be fucking kidding me!” when Safin saved that match point in that tiebreak (5–6) and sealed his legend. Federer had hit a superb drop-shot volley, but Marat answered with a perfect lob. On a 26-win streak, Federer had seen and lost his last chance. It would be his only loss on a hard court that year (50–1).

That match has also entered legend, because it glued us until the last shot. Safin had two match points on serve at 5–3 in the fifth, another at 5–4, and two more at 6–7. I was laughing-crying when Federer saved No. 6 at 7–8, as it felt unreal. But then, on No. 7, Safin went for that infamous backhand down the line, saw Federer fall while chasing it down, and let his forehand paint the last stroke. Coached by Roger’s former coach Peter Lundgren, Safin would win the title against Lleyton Hewitt, but he’d never play another Grand Slam final. He had already entered tennis immortality, so be it. —Carole Bouchard

9.

2017 Australian Open Final, Federer d. Nadal, 6–4, 3–6, 6–1, 3–6, 6–3

Imagine possessing 17 Grand Slam singles titles and realizing you must have the courage to implement a significant change. Add the fact that your greatest rival held a 23–11 lead in your matches, including the three previous times you’d played each other on the court you’re about to compete on. This was what Roger Federer faced as he entered Rod Laver Arena to play the 2017 Australian Open final vs. Rafael Nadal. Eight years earlier, a five-set loss to Nadal in the finals had brought Federer to tears. There’d also been semifinal defeats Down Under in ’12 and ’14.

In 2017, Federer arrived in Melbourne ranked 17, largely the result of missing the last six months of 2016 while recovering from knee surgery. He’d also gone more than four years without winning a major. Nadal, also hindered throughout ’16, was ranked nine. Versus Nadal, the Federer backhand had frequently been exposed, primarily due to the Spaniard’s lethal left-handed crosscourt forehand. But on this evening, Federer committed to hitting his backhand earlier and harder. That step would prove decisive, kick-starting Federer’s entire game. Still, Nadal went ahead 3–1 in the fifth—at which point Federer played five of the greatest games of his career. Not just the backhand, but every other aspect of the Federer game sparkled as he earned a redemptive Slam triumph. Federer would go on to win Wimbledon that year and take another Australian title in ’18—his final major. Nadal too would continue to excel, winning another eight Slams. —Joel Drucker

8.

2019 Wimbledon Final, Djokovic d. Federer, 7–6, 1–6, 7–6, 4–6, 13–12

“Tennis is the most beautiful sport there is and also the most demanding,” wrote David Foster Wallace in String Theory, and this match is a stained-glass mirror reflecting the brightest and harshest rays of that truth. I came into this match as a Roger Federer fan, and so did most of Centre Court that day. Federer had just become the first player ever to reach 350 Grand Slam match wins en route to the final, and the world felt primed for another chapter in his glimmering storybook. Which only adds another layer to make what Novak Djokovic did that afternoon feel more impossible. With the stakes as high as ever and the crowd against you, it became the ultimate test of Billie Jean King’s idea that pressure is a privilege. I spent the longest final in Wimbledon history, all four hours and 57 minutes, on Do Not Disturb and clinging to the edge of my seat.

Federer served at 8–7 in the fifth, up 40–15, two championship points from what would have been his ninth Wimbledon and 21st Slam. I vividly remember thinking, This is it, as the camera cut to his wife, Mirka, unable to look, and the commentator saying, “Breathe in, breathe out,” while I tried doing the same on my couch. Then seven straight points from Djokovic. Seven! The crowd roar and buzz turned into deafening disbelief.

This was also the first year Wimbledon used a 12–12 final-set tiebreak, making this the first Slam final ever decided by it. Djokovic, the top seed, defended his title, winning 7–6, 1–6, 7–6, 4–6, 13–12 for his fifth Wimbledon and 16th major, widening their head-to-head rivalry to 26–22. He became the first man in 71 years to win Wimbledon after erasing match points in the final. Federer left without No. 21, without a ninth Wimbledon, and in what would be his last Grand Slam final appearance. After the match, I thought back to Wallace’s words. How can this not be the most beautiful sport there is? —Jordaan Ashley

7.

2017 Miami Semifinal, Federer d. Kyrgios, 7–6, 6–7, 7–6

If there’s been a better three-set men’s match in the past 25 years, I missed it. It wasn’t exactly a shock that these two would put on a show that year in Miami. At 35, and having spent much of 2016 recovering from a meniscus tear, Federer had already startled tennis with a 2017 return that instantly signaled a late-career revival, winning the Australian Open and Indian Wells. (It would turn out to be his best year since 2007!) Nick Kyrgios, for his part, had begun his season beating Novak Djokovic twice: At 21, was he becoming the player he had the gifts to be?

The scoreline alone announces a crazy-good match. A match that, really, came down to three gambler’s go-for-it second serves from Kyrgios, resulting in three crushing misses: one to surrender a first-set break he’d earned; a second in the first-set tiebreak at 9–9 that provided Federer with a set-point opportunity he capitalized on; the third at 5–5 in a third-set tiebreak that he’d lose on the very next point, smashing his racquet after failing to return a Fed serve out wide to his backhand. It wasn’t just how close it was, though. It was everything, or everything you might expect from two players with electrifying attack games: penetrating flat forehands (one from Kyrgios clocked at 119 mph); big serves to all parts of the box; balls taken as early as possible; why-not net rushes, nasty slices, uncanny backhands down the line. And clean, given the point-in, point-out audacity—and the noise from a Key Biscayne crowd that reached Davis Cup decibels. It was proto-Sincaraz, and it was mesmerizing. —Gerald Marzorati

6.

2001 US Open Quarterfinal, Sampras d. Agassi, 6–7, 7–6, 7–6, 7–6

Andre was 31, Pete was 30. The two best players of the ’90s, now in their twilight. Going into the match, Andre had won their last three meetings, 6–1 in the 5th in the 2000 Aussie semi, and then Andre bludgeoned him in the finals of Indian Wells and Los Angeles (yes, there was once a tournament in L.A.). “The feeling that you had walking onto a court with him, you felt like you were a part of something that was bigger than both of us,” Andre told me of Pete back in 2006. “The feeling was its own entity, its own animal, its own energy.”

In their round of 16 matches, Andre had battered an outmatched teenager who had beaten Pete at Wimbledon earlier that summer—Roger Federer—and Pete had beaten the defending champion, Pat Rafter, in four sets.

Andre looked clean in head-to-toe black, ditto for Pete in white. Pete was on fire from the beginning, dialed in, hitting his spots with that perfect serve, demonstrating his uncanny athleticism, point after point, game after game. Andre in free flow was a beautiful thing to see. He could not have played better. Murdering the ball, penetrating the court to Pete’s backhand, over and over. But Pete was knifing the backhand with great success and then ripping it with a remarkable ferociousness that for Andre was hard to forget. When Pete established that he could hang with Andre a little from the baseline, that meant trouble. Neither player lost his serve, but after losing the first-set breaker 10–8, Pete won the next three breakers.

To watch it now is amazing. Tennis is no longer played like that. The evolution of hyper-carbonated ground strokes coupled with the slowing of the courts no longer allows for Pete’s style. A year later Pete would beat Andre to win the Open, 6–4 in the fourth. It would be the last pro match Pete ever played. —Craig Shapiro

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP FOR THE TSS NEWSLETTER

The Top 25 Matches of the Century So Far — 5 - 2

5.

2005 Australian Open Semifinal, S. Williams d. Sharapova, 2–6, 7–5, 8–6

As 17-year-old Maria Sharapova stepped to the baseline to serve for the match in the second set, up 5–4 and having yet to be broken, it seemed for all the world like an inflection point. She’d used the depth and angles of her ground strokes to dominate Serena Williams in the first set (6–2), as she had in the previous year’s Wimbledon final and WTA Championships. Williams had undergone knee surgery at the end of 2003, and through 2004 was not the player—the crushingly dominant player—she’d been from late in the winter of 2002 through the spring of 2003, a stretch during which she, at one point, held all four Grand Slam titles. Was she, at 25, now on the way to…done? She was not.

A revivified Williams forehand and a ghastly double fault at 15–40 evened the set, which Williams went on to win 7–5 after breaking Sharapova again. Set 3 was 66 minutes of breathless tension and fight in the cauldron created by the Australian summer heat. Maria’s yelps grew louder. Serena’s glares grew longer. The baseline rallies left both of them gasping for air. Once again, Sharapova secured a late break and was serving for the match at 5–4. Once again, she failed to get it done, despite holding three match points, an epic almost—overwhelmed or wrong-footed by some of the most daring forehands Williams would ever strike. Williams eventually prevailed 8–6, went on to win the final—and went on (inflection point!) to become Serena. Along the way, she never lost to Sharapova again. —Gerald Marzorati

4.

2009 Australian Open Semifinal, Nadal d. Verdasco, 6-7(4), 6-4, 7-6(2), 6-7(1), 6-4

If you are a true tennis fanatic, there’s something about waking up in the middle of the night to watch a big match. It just means more when you have to set your alarm for 3:30 a.m. to watch a spectacle unfold.

In the case of the 2009 Australian Open semifinal between Rafael Nadal and Fernando Verdasco, sacrificing a little bit of sleep was no price at all. What unfolded was an instant classic—a five-hour and 14-minute marathon of the utmost quality that ended at 1:07 in the morning (9:07 EST!). What I remember most about the match was the absurdity of the baseline rallies. Even Alcaraz vs. Sinner matches would be jealous of what Nadal and Verdasco produced from the back of the court.

No statistic can do justice to what we saw with our own eyes. But if you somehow missed it, there is proof in the numbers. Just how good was this tennis match? Verdasco blasted a ridiculous 95 winners…and lost! Nadal made only 25 unforced errors. That’s right, of 385 total points played, a mere 25 ended with a Nadal mistake.

Seventeen years later, I still can’t decide how I feel about the match ending on a Verdasco double fault. On the one hand, that’s not how any legendary contest should ever end. On the other hand, it sort of augments Verdasco’s career-long role as a tragic hero.

Although a loss to Federer in the championship two days later would have done nothing to diminish Nadal’s semifinal feat, the fact that he went on to lift the trophy—after yet another five-set thriller against Federer—allows the Nadal-Verdasco match to live in even higher echelons of tennis lore. —Ricky Dimon

3.

2024 Madrid Open Final, Swiatek d. Sabalenka, 7–5, 4–6, 7–6

The crown jewel in one of the tour’s best rivalries. Swiatek won the first set of this final surgically enough, as you might expect given her ridiculous résumé on the dirt. But from early in set 2, Sabalenka found whichever area of the court she liked with her titanic ground strokes, forcing the modern Queen of Clay to play the rest of the match on the back foot. Swiatek did whatever she could to jam up the gears of the hostile ball machine on the other side of the net: anticipating putaways to her forehand and sliding them past Sabalenka for crosscourt passing shots; counterpunching deep backhands on the run; attacking early and with venom in the rare peaceful moments in a rally that Sabalenka did not dominate. Each woman executed her strategy to near-perfection, whittling the margin for error down to nothing.

Sabalenka thwacked her way to two championship points at 6–5 in the third set, then another in the deciding-set tiebreak. Swiatek erased one with a purposeful forehand winner—off a Sabalenka return that wasn’t too shabby either—and the other two fell away thanks to Aryna’s suddenly nervous, uncertain swings. Though Sabalenka had beaten Swiatek in the 2023 Madrid final, beating the Pole on clay remained a very real mental block. (Naomi Osaka would learn the same thing when up match point against Swiatek at Roland-Garros the next month.) Sabalenka saved a championship point herself with a pinpoint ace, but Swiatek’s greater reliability down the stretch proved the difference. At Roland-Garros in 2025, with Iga’s aura of invincibility somewhat dented after an uncommonly flawed clay season, Sabalenka got her revenge in a semifinal played at a similar standard for the first two sets before wilting in the third. The Madrid final remaining spectacular until the end makes it a tough act to follow, even for these two. —Owen Lewis

2.

2005 Wimbledon Final, V. Williams d. Davenport, 4–6, 7–6, 9–7

True to its status as tennis’ most important tournament, Wimbledon’s press seats are unsurpassed—close enough to the court that you can hear each player’s shoes squeak. And so, on Saturday, July 2, 2005, I occupied a seat on the north end of Centre Court, watching Venus Williams and Lindsay Davenport play one another in the final.

It was fascinating to see these two champions, raised within a 30-minute car ride of each other in Southern California. Both were hungry for a big result. Williams had last won a major in 2001, Davenport in 2000. While some rivalries revolve around contrasts, this one tilted on similarities: powerful ground-strokers, each able to repeatedly drive the ball deep and hard. Each had played excellent tennis in the semis, Williams beating defending champion Maria Sharapova, Davenport fighting hard to get past versatile Amelie Mauresmo.

Having won the first set, Davenport served for the title at 6–5. But Williams countered sharply and took the set in a tiebreaker. In the third, the quality of play picked up nicely, with power, precision, and movement rising to the occasion.

Then there came a moment neither will ever forget.

Williams served at 4–5, 30–30, and double-faulted. Facing championship point, Williams quickly gained control of the rally and laced an untouchable down-the-line backhand. Per the Wimbledon tradition of those years, there would be no tiebreaker. At 7–all, Williams broke Davenport and then held serve at 15—becoming the first woman since 1935 to win the Wimbledon singles title after facing championship point.

The day before the final, Williams had made the case for equal prize money to Wimbledon officials. By playing one of the greatest finals in the tournament’s history, she’d emphatically proved her point. Two years later, equal prize money became a reality at SW19—and this time, too, Williams won the title. All told, Williams and Davenport would play each other 27 times, Davenport winning 14. Of course, no one knew that this would also be the last time they’d meet—and, poetically, their final encounter proved a masterpiece. —Joel Drucker

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP FOR THE TSS NEWSLETTER

The Top 25 Matches of the Century So Far — 1

1.

2022 US Open Quarterfinal, Alcaraz d. Sinner, 6–3, 6–7, 6–7, 7–5, 6–3

We are here to celebrate, of course, that transcendent five-setter, where Jannik Sinner held match point before being undone by Carlos Alcaraz, where both players asserted themselves as the premier talents of their generation, where they produced dozens of rallies that defied lay understanding of what was possible in the sport, where they advanced the societal relevance and physical limits of tennis itself. Oh, not that one. I meant the other one.

Yes, I’m talking about the predecessor: the 2022 US Open quarterfinal, between a 21-year-old Sinner and 19-year-old Alcaraz. When the match concluded at 2:50 a.m, I felt I’d caught an illicit, long-awaited glimpse of the ATP beyond the “Big Three” era. Back then these two were still primordial goo. Alcaraz had won bigger titles. Sinner had been a top player for a little longer. But there was still so much to prove. Neither one had yet reached world No. 1, won a Slam, beaten Novak Djokovic in a best-of-five, or even really figured out his own serve.

All those facts enhanced the spectacle. I am increasingly convinced that the best matches are those between nondominant servers who move beautifully. And at the time I was certain I had never seen kids so noodly in physique covering the court with such violence and flair. Without serves to win free points, both players had to deploy their ground strokes in inventive ways in order to gain any advantage in the rally. I am also convinced that the best matches are played between players who are learning, in real time, that they can do preternatural things. When Sinner slides into a screaming open-stance backhand, or Alcaraz leaps into the air for a behind-the-back passing shot, I see them writing their own styles into being.

Their rivalry was then in a state of naivete. It was just the fourth time these two had met on the pro level. You could see them noticing and adjusting to the other’s moves—say, sneaking over to a new return position to counter a wide service position, or reading the drop shot better and better. There was still mystery between them then. Now their knowledge of each other seems nearly total. By their own admission, they spend weeks of their lives on the practice court, studying, specifically, how to beat each other.

Thankfully this hasn’t made their tennis any less enthralling. In 2025 they completed a trilogy of Sincaraz Slam finals. It began on the clay of Roland-Garros, with a match that mirrored the dizzying level and scope of this one. If the 2022 US Open was an omen of greatness, then the 2025 Roland-Garros was the fulfillment of that promise, the formal pronouncement of a new era in men’s tennis. By that time they were stronger, wiser, more technically sound, playing for even higher stakes. A few weeks after that match in Paris, still feeling its reverberations, I found myself on a familiar years-old highlight reel, looking back, once more, to a past made richer by the future now visible. —Giri Nathan

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP FOR THE TSS NEWSLETTER

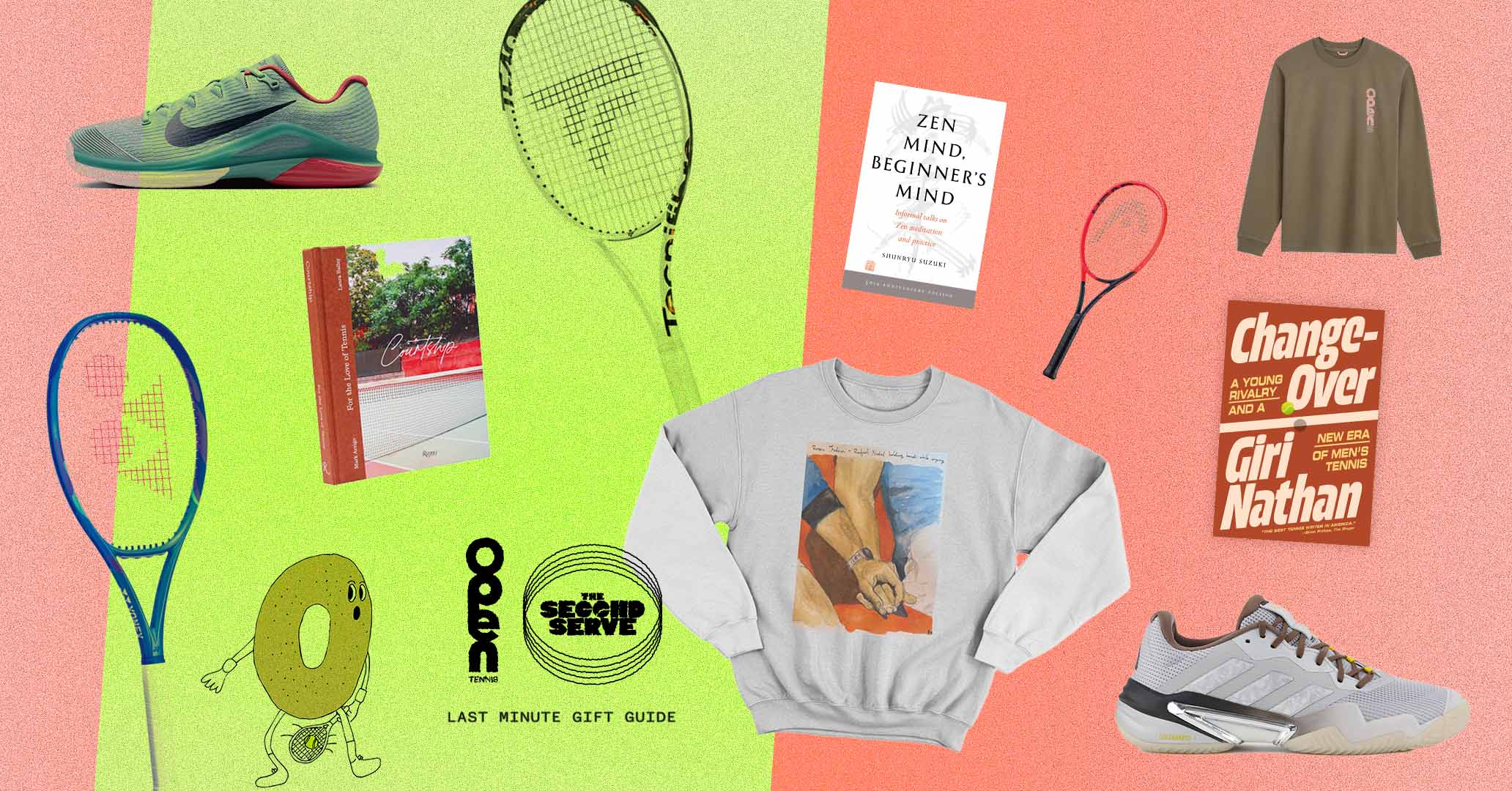

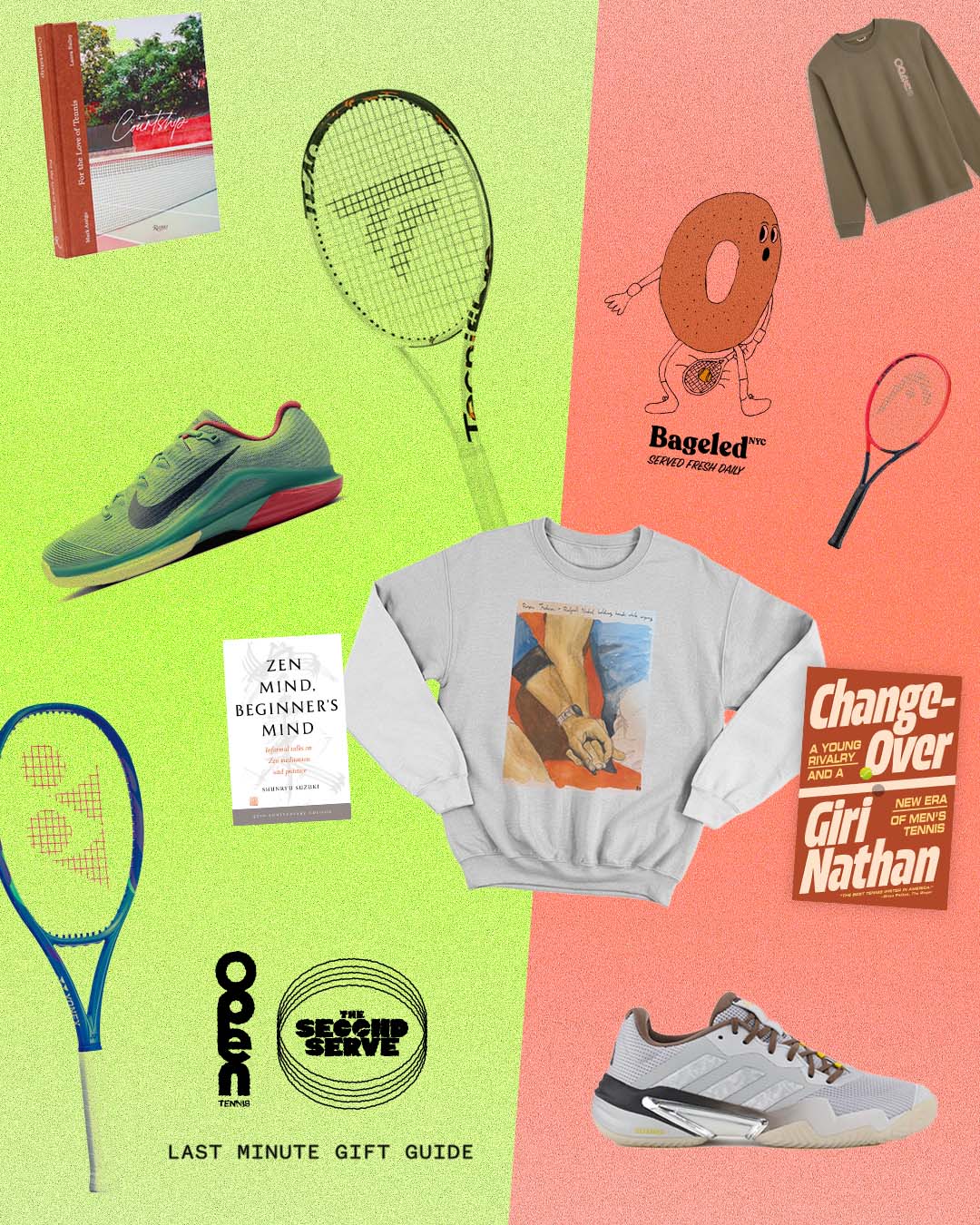

TSS Holiday Gift Guide

Net Gains

Net Gains

Our last-minute tennis gift guide.

Our last-minute tennis gift guide.

By The Second Serve

December 5, 2025

While the tennis fan in your life is likely still white-knuckling the interminable offseason (six whole weeks!), there’s still time to ply them with tennisy gifts this holiday season. According to our staff and contributors, here’s our short list of TSS-approved gifts that will still arrive in time for your holiday of choice. Or just buy this stuff for yourself on Boxing Day to make up for a disappointing haul. Either way, we’re here to help suffering tennis enthusiasts make it to the start of the Australian summer with their sanity intact. It’s been a very trying winter, and it hasn’t even started yet, so spread holiday tennis cheer whether it’s at the indoor courts, in the racquet bag, or on St. Kilda Beach in Melbourne.

Brain Dead x adidas Barricade 13

They’re finally here. L.A. icons Brain Dead have partnered with adidas on a pair of Barricade 13s—the latest iteration of one of the longest-running on-court tennis shoes in the game—featuring looks that bring sport and casual wear together as seen on TSS’s own David Bartholow and in OPEN Tennis Vol. 2. Known for its stability, torsion system, and lockdown fit, the Barricade has been a mainstay on the court for decades, quietly marking its 25th year in 2025, according to Tim Newcomb in our weekly newsletter. Key details include a translucent outsole exposing speckled underlays, metallic silver 3-Stripes, co-branded sock liners, and custom tongue branding. It really is the most exciting performance shoe release in recent memory.

TSS x Eddie Martinez

Solinco Whiteout 305

This custom racquet combines Solinco’s expertise in crafting sporting equipment of quality, performance, and versatility with Brooklyn artist Eddie Martinez’s signature tennis ball and “blockhead” motifs to create a stylish racquet for discerning players and fans. The Whiteout is designed to offer players with faster swing speeds a precise control- and feel-oriented racquet. Each racquet comes with a copy of The Second Serve’s new print magazine, OPEN Tennis Vol. 1, Solinco Hyper-G racquet strings, as well as stickers and dampeners bearing Eddie Martinez and The Second Serve’s designs. Sold exclusively by The Second Serve.

Yonex EZONE 98

Our creative director David Bartholow has been playing with previous iterations of the Yonex EZONE for years, and while he was devoted to them, they could be a touch stiff, so balls tended to fly unexpectedly. The new, eighth-generation EZONE, though, is a “flawless update,” he says. The EZONE 98 has a thinner beam and is significantly more maneuverable than the previous versions and has a “ridiculously buttery feel” when paired with Poly Tour Pro 125. “In moments, whether delusional or not, you get the sense that you can do almost anything with this instrument,” says Bartholow.

Nike Zoom Vapor 12

After a few wayward years where Nike inexplicably veered from the foolproof Vapor platform they introduced in 2012 by way of Roger Federer, the course has finally been corrected. Not only that, says Bartholow, but the new Vapors might be the best ones yet. While it has lost some of that amazing plushness from previous generations, the shoe is somehow infinitely more durable: “Pairs that once evaporated in six weeks are now lasting me three to five months of playing five days a week.” The addition of a TPU layer to the toe and primary wear areas brings much-needed protection that only contributes to the improved durability. “They’re also a touch longer and more true to size, which my toes appreciate. Whereas previous versions required zero break-in period, these do require a few sessions, but nothing crazy. As a self-professed Vapor head, one could say I’m downright elated that Nike understands how important it is to preserve this shoe,” says Bartholow.

Tecnifibre TF40 305

Patrick Riley, of the band Tennis, was a highly touted junior player before he burned out, as many of us do, so when he picked up tennis again (the sport, that is) recently, he was overwhelmed. “Getting back into tennis after taking a 15-year break, I was entirely lost on what I wanted,” said Reilly. As a junior he played with Head Prestige frames, “but a lot has changed: Balls are slower, I am slower and weaker. (This is not entirely true: Reilly’s slick game was photographed for OPEN Tennis Vol. 2, and we can confirm he still commands the court.) “The TF40 305, with the 18×20 string pattern, was the perfect choice to bridge the gap; it has the feel and control of a Prestige but significantly more power and is light enough to customize,” he said.

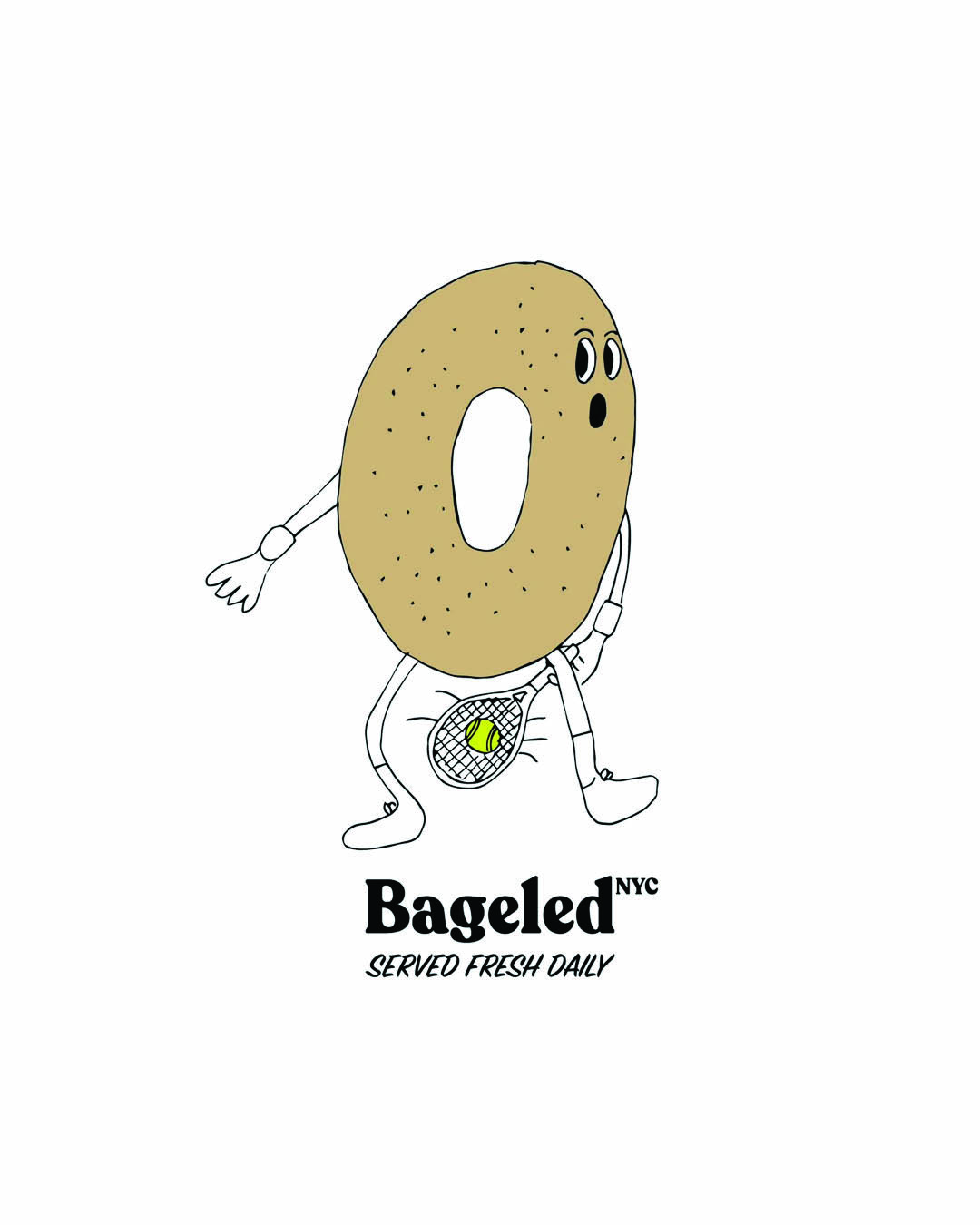

“Tweener” Tee

When the US Open released its official merch, one design looked strangely familiar. The Brooklyn-based brand Bageled NYC has been making small runs of tennis-centric merch and accessories that you can see worn by locals in the Fort Greene tennis scene, in Brooklyn. As reported in our Groundies column, their most iconic design features founder Sam Burns’ drawing of “Bagel Bud” hitting a vicious tweener while grinning. The shirt’s tagline, “Served Fresh Daily,” also happens to appear, verbatim, on the USTA’s bagel shirt. Accept no substitutes.

Open Tennis Long Sleeve Tee

New in, our midweight long sleeve T-shirt features the OPEN Tennis and The Second Serve logo on the backside and left chest (and has a standard fit that tapers slightly from the chest to the waist hem). It was designed with a wide rib collar, semi-raglan sleeves, and signature flatlock construction, which is all to say it’s extremely classy. Our latest muted colorway is perfect for indoor tennis season. Printed on Reigning Champ’s Midweight Jersey Standard Long Sleeve shirt.

Fedal Holding Hands Tee

It’s the LVBL x Stand Up To Cancer x The Second Serve crewneck sweatshirt, featuring the painting “Federer and Nadal holding hands while crying,” by the writer and artist Sam Anderson. Why not immortalize the tender moments surrounding Rog’s retirement in wearable form? All proceeds go to benefit Stand Up To Cancer.

Head Radical MP

Don’t be afraid of trying new gear! Mike Belgue of the sportswear brand Reigning Champ had been using Tim Henman-era Slazenger racquets for the past 15 years, firmly stuck in his glory days, until a friend at Head suggested he try the Radical MP. “Not only did I have less arm and shoulder discomfort, but I felt like I could get balls that were out of reach previously, and when I got my racquet on them, I had more control while also having more effortless power,” he wrote in OPEN Tennis Vol. 2. “It still has a ton of touch while feeling confident with plow-through, but it’s so much more compliant than my old racquet. The equipment change renewed my vigor for the sport, and I’m sure it’s added years to my arm.”

Tecnifibre X-One Tennis Balls

Let’s be honest: All the tennis lovers in your life want for the holidays is tennis balls. “The Tecnifibre X-One is a remarkable ball that is insanely durable,” said Brain Dead’s Kyle Ng in OPEN Tennis Vol. 1. “I don’t know what X D-Core is, but it’s doing its job! This is a heavy ball that you don’t need to toss in the dumpster or ball machine after the first few hits. It can go the distance. And an extra ball per can is everything.” Nothing embodies optimism more than a fresh case of balls!

Courtship: For the Love of Tennis

Writes editor David Shaftel in OPEN Tennis Vol. 3 (out next month!), “Conceived by the model, writer, photographer, and activist Laura Bailey, the hefty, best-in-class Courtship features nearly 200 pages of images by the landscape photographer Mark Arrigo. Arrigo’s photos of courts are diverse, moody, and comprehensive. The photos are accompanied by a section of essays by the likes of Bailey, as well as Judy Murray, Peter Gabriel, Billie Jean King, Anna Wintour, and many more boldfaced names. The book is a thorough encapsulation of Bailey’s tennis life, an intoxicating mix of high- and lowbrow courts.”

Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind

“In Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, Shunryu Suzuki distills shoshin (beginner’s mind) into a reader-friendly guide that sheds light on the life- and tennis-applicable facets of Buddhism,” said our resident coach, Simon Hegelund, in OPEN Tennis Vol. 2. “I recommend this to players who tend to put pressure on themselves, are highly ambitious, and perhaps find themselves stuck. In the beginner’s mind, everything is practice.”

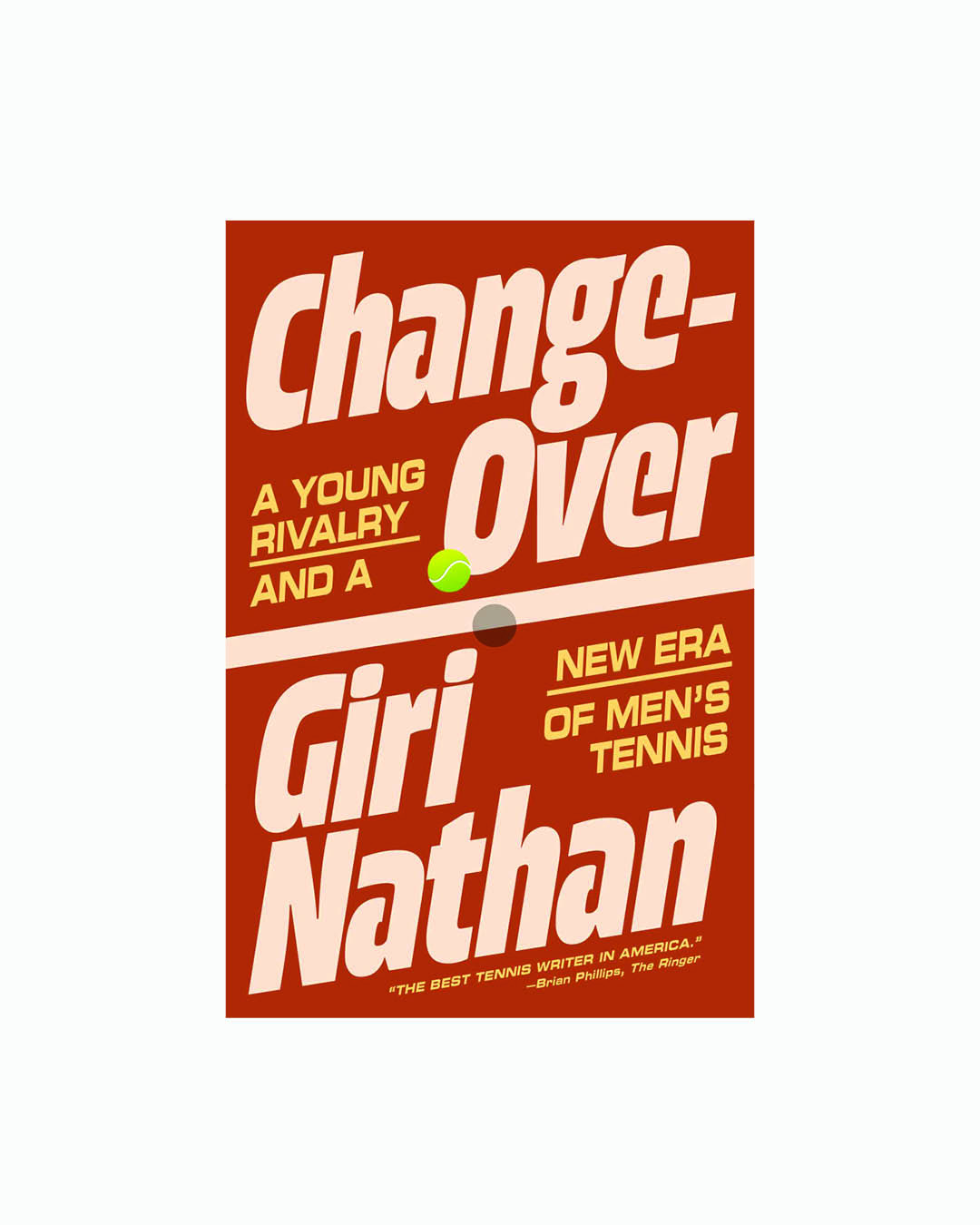

Changeover: A Young Rivalry and a New Era of Men's Tennis

Lauded by everyone who lauds books, Changeover is the definitive text on the rivalry between Carlos Alcaraz and Jannik Sinner, by the definitive tennis writer of his generation, Giri Nathan (who also happens to be the writer of our weekly newsletter). Our resident book critic Patrick Sauer called it a “fantastic, propulsive, deeply considered look at the Sincaraz phenomenon.” It’s required reading for fans of both the modern game and literary sportswriting.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP FOR THE TSS NEWSLETTER

Fuzzy Memories

Fuzzy Memories

A Q&A with Nicholas Fox Weber, author of

The Art of Tennis.

By Patrick Sauer

November 6, 2025

Fuzzy Memories

A Q&A with Nicholas Fox Weber, author of The Art of Tennis.

By Patrick J. Sauer

November 6, 2025

If asked to describe the ideal of tennis artistry, most fans would pull from a familiar canon: the angled dead-on-arrival drop shot, a feathery one-hand backhand slice, a down-the-line buggy whip forehand, a leaping at-the-apex overhead smash, a perfectly placed just-inside-the-baseline lob, or perhaps the Serena Special, a walk-off ace-up-the-tee. Outside of the underarm quick serve, there is no wrong answer—Michael Chang cramping in his ’89 French Open victory excepted—the beauty is in the eye of the match-watching beholder.

There is, however, an entirely different way of answering the question. Proper responses could include Caravaggio, William Shakespeare’s Henry V, Rene Lacoste’s alligator (er, crocodile?), Katharine Hepburn, Diego Rivera, Tom and Jerry, Babar the Elephant, Errol Flynn, or former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, all of whom warrant a sporting mention in Nicholas Fox Weber’s superb new book The Art of Tennis.

Weber, who turns 78 next month, is the acclaimed author of 15 art and architecture books and a lifetime tennis devotee who only began opining on the sport, in print, in the past decade. He’s made up for all that lost time and more in The Art of Tennis, as it’s one of the most idiosyncratic, enlightening, and enjoyable books about the inspired creativity the sport has given rise to that I’ve come across. Weber introduces a menagerie of fashionably erudite characters like Bunny Austin, the man who, at Wimbledon 1933, broke down the no-shorts barrier, and art critic Henry McBride, who had a “musical portrait” written in his honor called “Tennis” with notes and tempo listed as “point, set, match.”

Weber makes time for familiar players of the past like Bill Tilden, Helen Wills, Althea Gibson, and Guillermo Vilas, but the author goes wherever the ball bounces. There are detours to the Middle Ages, to mid-century Broadway, to present-day Africa, and to meet a few of his personal friends, including his dogged tennis partner Nick Ohly. There is a warm chapter on Ohly, who died of a massive heart attack during a midday lawn match in New Haven, Conn., one of countless rolling matches over a long friendship, moments after saying to Weber with a smile on his face: “Let’s keep going. It’s such a nice day, and the game is so much fun.”

It really is. From his apartment in Paris, Weber spoke to The Second Serve about the art—and soul—he called upon in writing his first book about the game he loves.

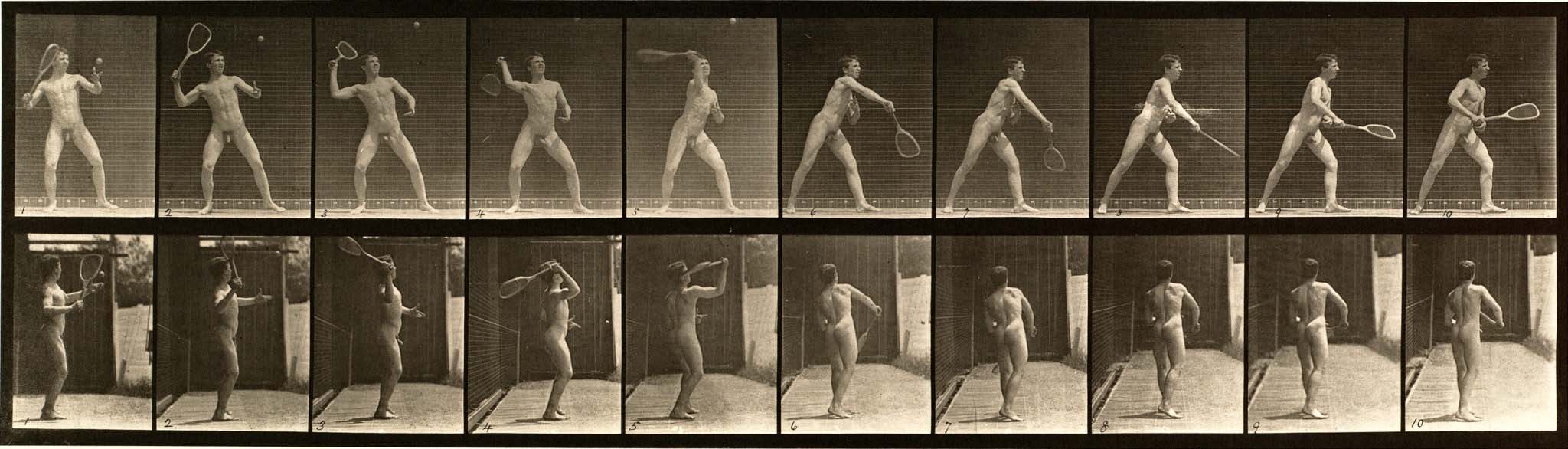

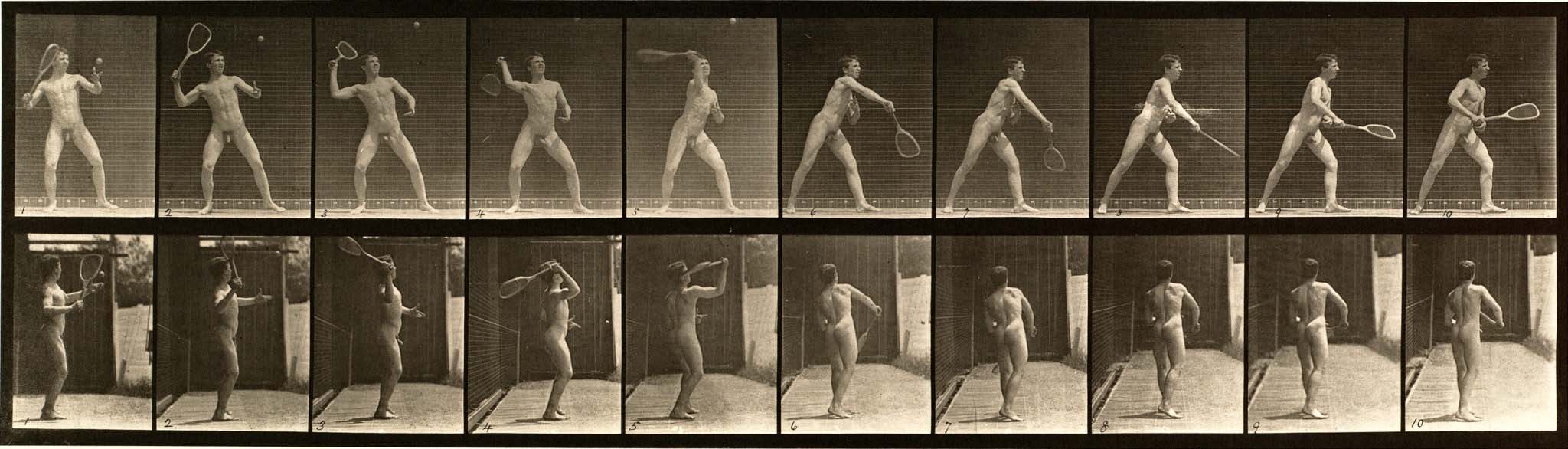

“Animal Locomotion,” Plate 294, Eadweard Muybridge

“Animal Locomotion,” Plate 294, Eadweard Muybridge

I swear this isn’t asked in jealousy, but how did you come to live in both Ireland and Paris?

In my early 20s I fell in love with a remote corner of West Cork, so in the ’80s my wife, Kathy, and I bought a small house overlooking the sea. Over the years it’s become more and more of our home. The town didn’t have anywhere to play tennis, so we built a lovely court set out in a field. It’s got fake grass, an Astroturf that survives the rain very well. It’s wonderful.