Naomi Osaka is Always Moving

Naomi Osaka is Always Moving

As she rounds back into form, the four-time Grand Slam champ is consistently compelling.

As she rounds back into form, the four-time Grand Slam champ is consistently compelling.

By Ben RothenbergAug 8, 2025

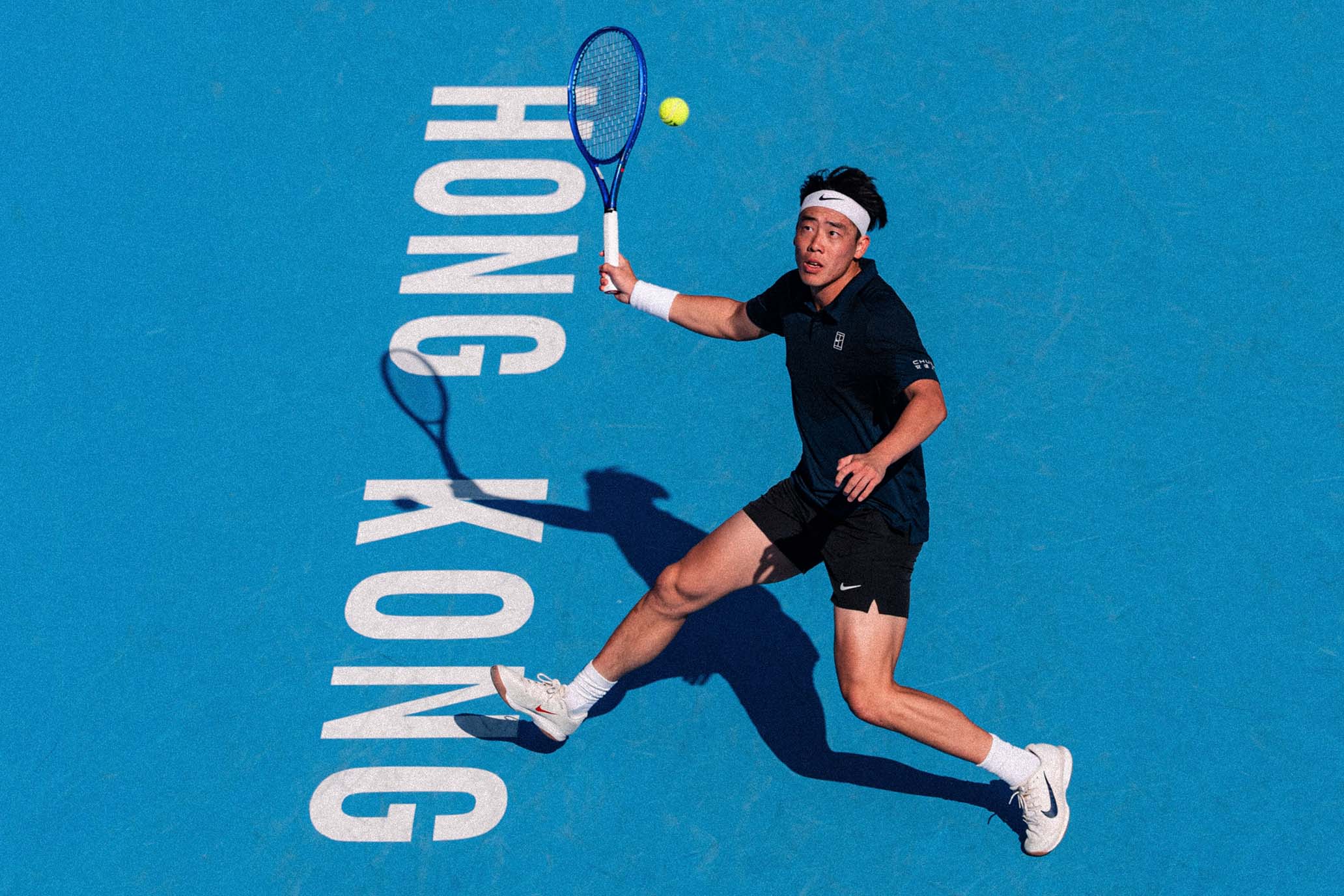

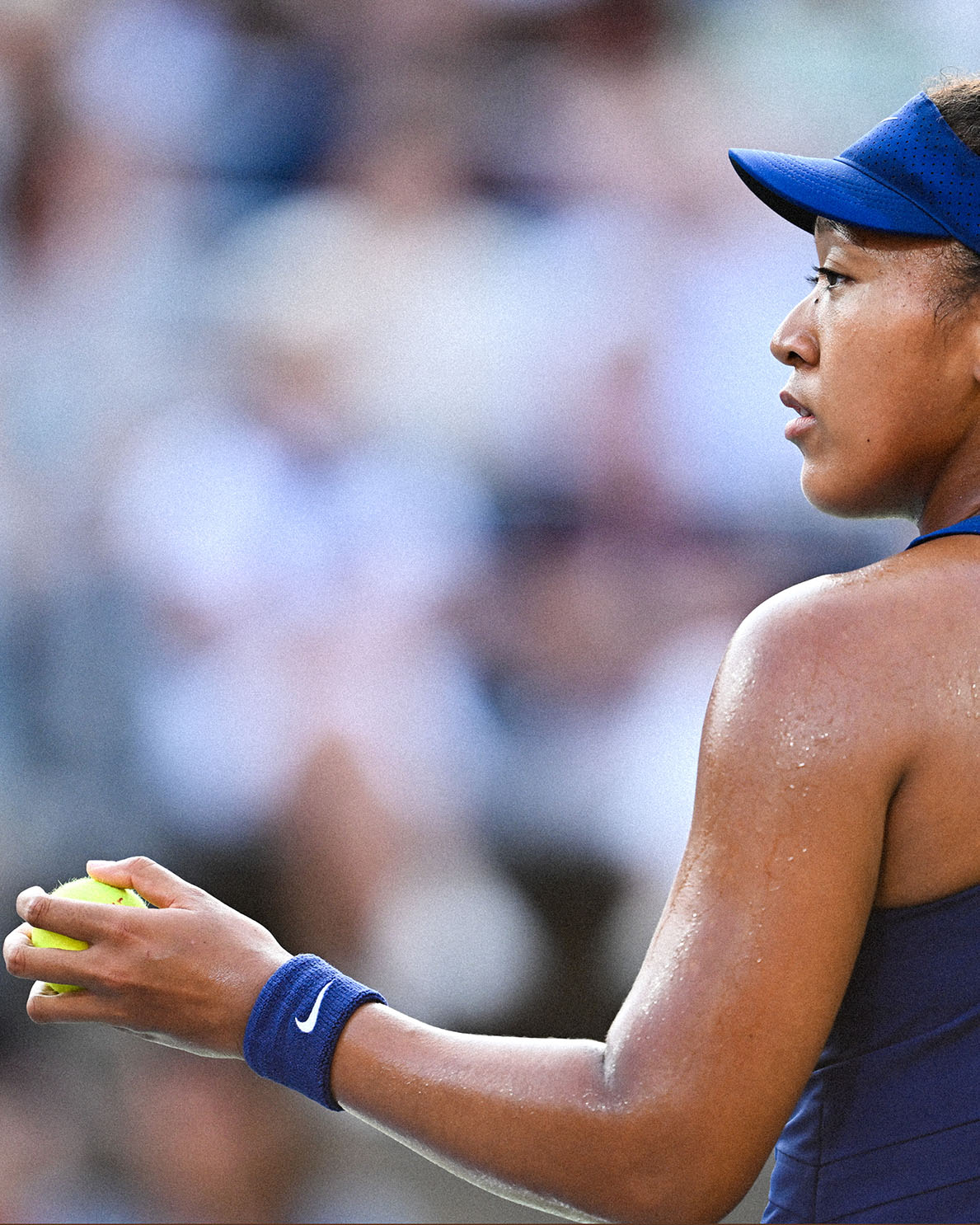

Naomi Osaka is all business during her finals run in Montreal. // Getty

Naomi Osaka is all business during her finals run in Montreal. // Getty

There are three predominant ways folks discussed Naomi Osaka’s resurgent run to the final in Montreal this week. All three of them are technically correct, but all three, I think, miss the real factors at play in her apparent return to competitive relevance.

The first is that Osaka’s great run was thanks to the arrival of Tomasz Wiktorowski, the veteran coach who guided Agnieszka Radwanska and Iga Swiatek through the strongest stretches of both of their careers.

Wiktorowski is a great, proven coach, and he has surely been a positive presence this week in Osaka’s corner. But I don’t think that any coach can change the fortunes of a player within just a few days of meeting her in any meaningful way. Wiktorowski almost certainly represented a positive vibe shift, but it’s tough to know from one week what the long-term returns will be on this partnership.

More than the addition of Wiktorowski, what I think helped Osaka’s equation pay short-term dividends was the subtraction of Patrick Mouratoglou.

Mouratoglou is a smart guy and a savvy businessman with a lot of good ideas about how to grow tennis, but I was never convinced he was a good match for Osaka. His best-known chapter as a coach—helping Serena Williams usher in a second act that put her in the Greatest of All Time conversation—might’ve augured well for his work with Osaka; Osaka also did very well for herself when she previously employed a former Williams coach in Sascha Bajin. But Williams was much closer to peak form when Mouratoglou arrived in 2012 than Osaka was when Mouratoglou came to her late last year, and there’s not a one-size-fits-all fix to reinvigorating the career of another established superstar.

Mouratoglou, too, also didn’t seem to have the focus or hunger for Osaka that he had while proving himself with Williams, spending lots of time and energy and oxygen on his own media pursuits in ways that only served to increase the noise around Naomi. Without any big titles together, the most memorable moment of their partnership might’ve been when Osaka was asked, at a pretournament press conference, what she thought of Mouratoglou’s comments on French television during Roland-Garros that “we’re in a period in women’s tennis where there are no major stars.”

“I didn’t hear that,” Osaka said, betraying some annoyed surprise. “But I don’t know, maybe we should do a powwow about the things that he says. Totally off topic, but sometimes I scroll on Instagram and he pops up and I’m like, ‘Oh wow,’ and then I keep scrolling.”

Osaka has had no trouble generating headlines and attention of her own for the past five years, even without a force multiplier in her corner.

The second misconception is that this week in Montreal was Osaka’s best run since returning from pregnancy and maternity leave. This is true, but I think it’s the wrong framing to use when discussing what Osaka is rebounding from, exactly; she had already slipped far from her peak form well before becoming pregnant in late 2022 and missing the entire 2023 season.

The six matches in a row that Osaka won in Montreal were the longest win streak she’s had since what I think was the peak of her powers: a 23-match win streak that ran from summer 2020 into spring 2021, including her second titles at both the US Open and Australian Open.

In my biography of Osaka, I borrowed a term from Neil Tennant of the Pet Shop Boys to describe Osaka during that time: It was her “imperial phase.” Everything she touched seemed to turn to gold, and she seemed ready to run up the score on court and off; the New York Times Style section wrote a feature called “How Naomi Osaka Became Everyone’s Famous Spokesmodel.”

But right at that apex, Osaka started slipping steeply and then spectacularly, culminating with her withdrawal from the 2021 French Open after a standoff with tournament organizers over mandatory post-match press conferences. Osaka took a few short breaks after that but felt compelled to return to play the Tokyo Olympics—where she lit the cauldron in the Opening Ceremony—and to attempt to defend her title at the US Open.

From the start of 2018 to the 23-match win streak that ended at the 2021 Miami Open, Osaka was 111–36 (75.5%); from then until the beginning of her maternity leave, she was 20–15 (57.1%). Since her maternity leave she’s been 49–30 (62.0%), including the Montreal run that bumped her win rate up by a couple percentage points. I am not sure that whatever derailed Osaka back in 2021—perhaps the various mental health struggles she revealed, perhaps a loss of the hunger that once propelled her, perhaps something else entirely—has yet been adequately addressed.

This leads into the third and most important thing that I think the narratives got wrong about Osaka in Montreal: that, with this run, she is clearly “back.”

Yes, Osaka is likely to be seeded at the US Open later this month, her first time being seeded at a major since her title defense at the 2022 Australian Open. That’s a return to a certain status, to be sure.

But as someone who struggled for more than a year to figure out where her story was headed while writing a mid-career biography of her, the thing I am most confident of about Naomi Osaka is that she remains a moving target, difficult to keep in clear focus with any lens, for any length of time. She’s still growing, still evolving, still learning, still stumbling, still struggling. All humans are doing those things, sure, but with Osaka there’s always been a certain rawness to her visible turmoil that makes it all the more stark, vivid, and captivating.

Her final match in Montreal was, ultimately, a brutal encapsulation of this. Osaka was the much better player at the start of the match, taking the first set 6–2 against the inexperienced Victoria Mboko, a local favorite for the Canadian crowd. But when the match should’ve still seemed firmly in her grasp early in the second set, at 6–2, 1–1, Osaka began to crash out.

First, a crosscourt forehand by Mboko landed near the line; Osaka had expected an out call that didn’t come and grew extremely frustrated extremely quickly, letting the tension of the moment show. When her first serve was called out on the next point, she sarcastically shouted, “I believe you, 100 percent!” toward the chair umpire. When Mboko broke for a 2–1 lead, Osaka dropped her racquet in exasperation, giving both Mboko and the crowd hope that the front-runner might be stumbling.

Indeed she was, and she never got it back together in the second hour of the match, or even after it. Several times she raced through her own service games, wanting to start the next point just a couple seconds after the previous one.

After Mboko won 2–6, 6–4, 6–1, a despondent Osaka left the court and had to be cajoled back on by a WTA handler for the trophy ceremony.

Her eyes still watery, Osaka sounded unimpressed by the Montreal crowd cheering for her for the first time all night as she stood at the microphone. “Thanks, I guess,” she said as she began.

Osaka’s speech lasted only 20 seconds—she conspicuously didn’t mention or congratulate Mboko—and ended with her coldly saying, “I hope you guys had a good night.” Predictably, many of the locals took umbrage at what they saw as a slight to their young new star hero.

Osaka skipped her mandatory post-match press conference, but a couple quotes from her were released hours later, in which she admitted how quickly her own mind can turn on her and acknowledged her slight of Mboko.

“I think it’s kind of funny—this morning I was very grateful,” she said. “I don’t know why my emotions flipped so quickly. But I’m really happy to have played the final. I think Victoria played really well; I completely forgot to congratulate her on the court. Yeah, I mean, she did really amazing.”

Osaka’s second answer accepted the positive framing she was offered about how successful her first week with Wiktorowski had been.

“Yeah, obviously this tournament went really well,” she said. “It could have went better, but that’s just me being picky. I think it was a really good first tournament, and I hope that we can continue.”

Because they are often so compellingly unvarnished, Osaka’s emotional reactions to defeats often gain more attention than her victories. That pattern may well repeat itself after this loss, particularly after runner-up Karen Khachanov was wildly effusive about Ben Shelton in his post-loss remarks hours later in Toronto.

Osaka is aware of this trend and lamented it in a post on Threads hours after her loss at Wimbledon.

“Bro why is it every time I do a press conference after a loss the espns and blogs gotta clip it and put it up,” she wrote. “Wtf, why don’t they clip my press conferences after I win? Like why push the narrative that I’m always sad? Sure I was disappointed a couple hours ago, now I’m motivated to do better. That’s human emotions. The way they clip me I feel like I should be fake happy all the time.”

Osaka is right: she’s definitely not “always sad.” She’s not “always” anything, really. Except, perhaps, continually compelling. No matter her coach, no matter her ranking, no matter if we—or she herself, even—have any idea what she might do next.