Wham, Bam, Thank You, Slam

Wham, Bam, Thank You, Slam

The Australian Open’s 1-Point exhibition is both ecstasy and agony.

The Australian Open’s 1-Point exhibition is both ecstasy and agony.

By Owen LewisJanuary 14, 2025

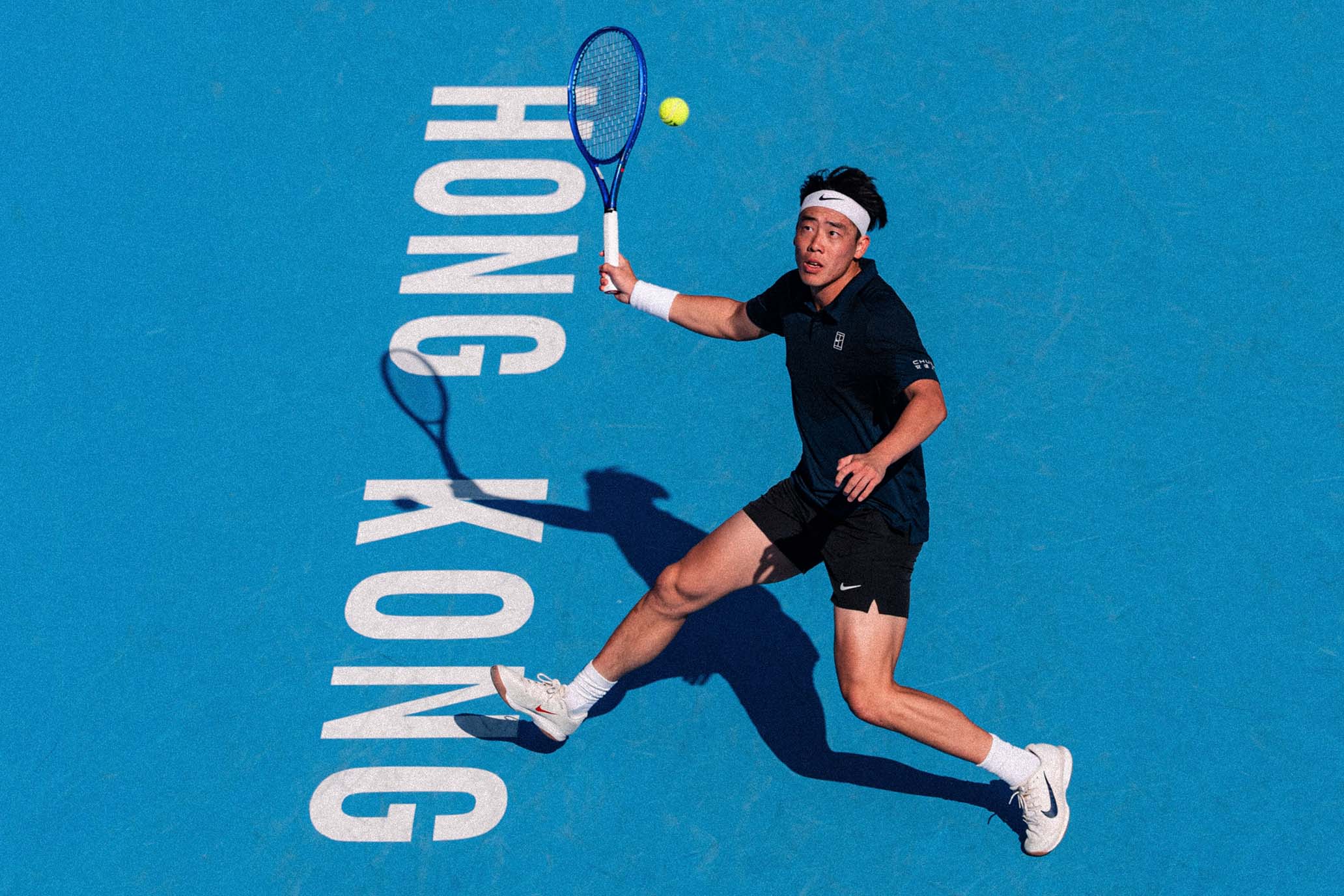

1-Point Slam runner up, Joanna Garland. // Getty

1-Point Slam runner up, Joanna Garland. // Getty

If anything in the main draw of the 2026 Australian Open beats the 1-Point Slam for drama, it’ll prove a wildly successful tournament.

The AO has struck gold with its exhibition, evidenced by the jump in prize money from $50,000 to $1 million in just its second year. One point deciding a match—just one point!—presents a very specific kind of gut check that is very different from an official match. Even top professionals might not pass it. Main-draw matches are their own gauntlet of nerves, but players can find solace in repetition. Miss a backhand on one point, and you’ll have a chance to right the wrong on the following point. The 1-Point Slam offers no space for mistakes. So do you take your fate into your own hands, or push the ball down the middle of the court and hope your opponent misses? On Wednesday night, plenty of high-ranked pros picked the latter option. Some of them just plain choked.

Jannik Sinner, the two-time defending champion of the Australian Open and a player as impervious to emotional vulnerability as I’ve ever seen, lost to amateur Jordan Smith when he hit a serve that fluttered weakly into the net. (Pros in the top 100 are allowed only one serve, while lower-ranked players and amateurs get two.) Carlos Alcaraz landed several forehands onto the baseline in a rally against Maria Sakkari, only to net one of his favorite drop shots. Six-time major champion Iga Swiatek beat top male pros Flavio Cobolli and Frances Tiafoe but sent a forehand way long against 71st-ranked Pedro Martinez.

Rod Laver Arena was not only sold out but truly invested in the points, which is more than quite a few official matches can say, even those with the highest stakes. Twenty-four-year-old, 117th-ranked Joanna Garland was the breakout star of the night—she outmaneuvered Alexander Zverev with a hard backhand down the line, got Nick Kyrgios to miss a return (he smashed his racquet afterward, because of course), and drew a backhand error from Donna Vekic. Even as Garland lost the final to Smith, she couldn’t stop smiling. It was incredible theater. The hosts maintained a steady stream of banter and asked players about their tactics, which was annoying at the best of times. Still, I imagine the 1-Point Slam did more to intrigue casual or previously uninterested tennis watchers than most official matches.

Unfortunately, the event also has some kinks it badly needs to work out. And they’re a bigger deal than the numerous delays between rounds and the first point kicking off 41 minutes after the scheduled start time. As the 1-Point Slam progressed past the early “matches,” with the top seeds falling, it became sickeningly clear that while players to whom the money would be transformative had a real chance of winning, several would have their dreams dashed in the space of a few moments. In those moments, the jokey, game-show-esque aesthetic of the 1-Point Slam proved woefully inadequate.

Take Martinez, who lost to Smith in the semifinals. Before he sent a tight, tight backhand down the line wide, he probably considered the million his for the taking. He was the only male professional left in the draw at that point. He is 28 years old and ranked 98th in the world, 47 spots below his career high. Though he has made more than $5 million in prize money over the course of his career—singles and doubles combined—that money has been spread out over many years. He has won just one title; the last event he played before the Australian Open was on the Challenger Tour. This would have been the best payday of his life. He had more riding on this one point than he will when he plays his first-round match at the Open or, in all likelihood, in any match he’d ever played before.

When Martinez missed that backhand, the crowd roared in support of Smith. Martinez’s cry of “NO!” was audible for no more than a split second. But you could see the anguish on his face and in the way he drew his arm back to slam his racquet into the hard court, only to reconsider at the last second. He gamely shook Smith’s hand, and that was the end of his story; he appeared on the broadcast only once more, in a replay of his reaction. I’d screwed up my schedule and had to leave the event half an hour in, but I was glad not to be there for this, because I might have had to run out. A beaming host began interviewing Smith so fast Martinez couldn’t possibly have had time to make himself scarce, or perhaps vomit. I thought briefly that the tournament suddenly had far too much in common with Squid Game.

Mind you, the money meant a lot to Smith, too. He spoke of buying a house in Sydney, and I’m thrilled that he now can. The juxtaposition with Vekic, who repeatedly plugged her line of diamonds throughout the night, was also deeply unpleasant to watch. Imagine if the money had gone to Vekic instead after that. Imagine if Garland had understandably crashed out after missing a backhand in the final, when she’d spent the earlier rounds hitting so many good ones. Worse, imagine if Alcaraz or Sinner, who’d pocketed $2 million each just this week for an exhibition in South Korea, had beaten Smith in the final. I would like to believe that they’d have let an amateur or lower-ranked pro win, but given that both have taken enormous paydays at the Six Kings exhibition in Saudi Arabia, I’m not sure they’d be able to resist chasing the cash.

The 1-Point Slam is onto something—more than something. 2008 Bill Simmons is somewhere in a parallel universe arguing that this format should replace the main draw at the majors in a column laden with pornography references. The event manages to amplify the aspirations, nerves, and drama of a tennis match and condense it into a single point. But the game-show vibes in the late rounds need to go as soon as possible. The idea may be novel and unofficial, but the hopes and dreams of the unwealthy taking part are very real. The losers deserve a format that respects their disappointment.