The Saddest Generation

The Saddest Generation

The despair is palpable for the charter members of the "SadGen".

The despair is palpable for the charter members of the "SadGen".

By Owen LewisOctober 23, 2025

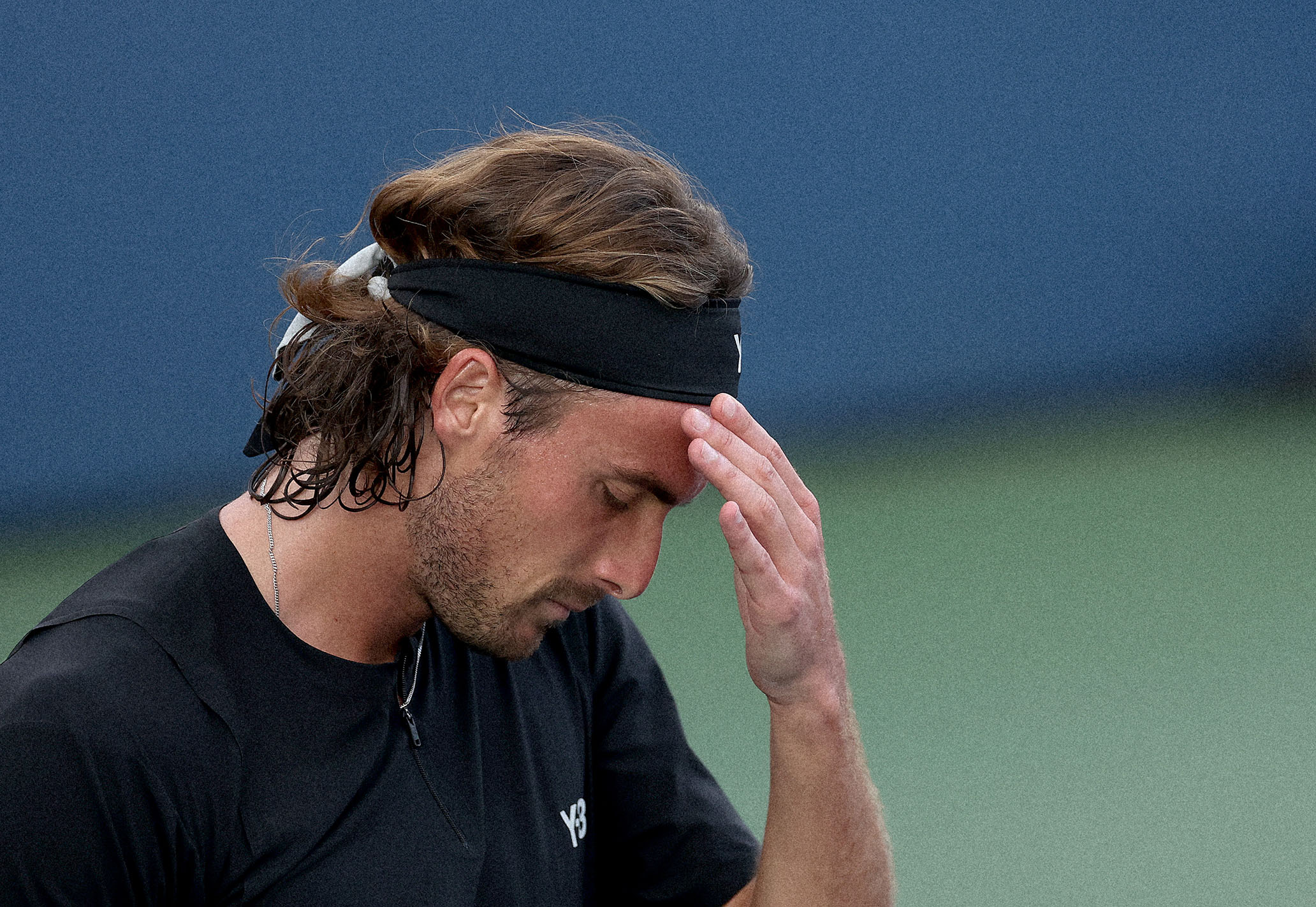

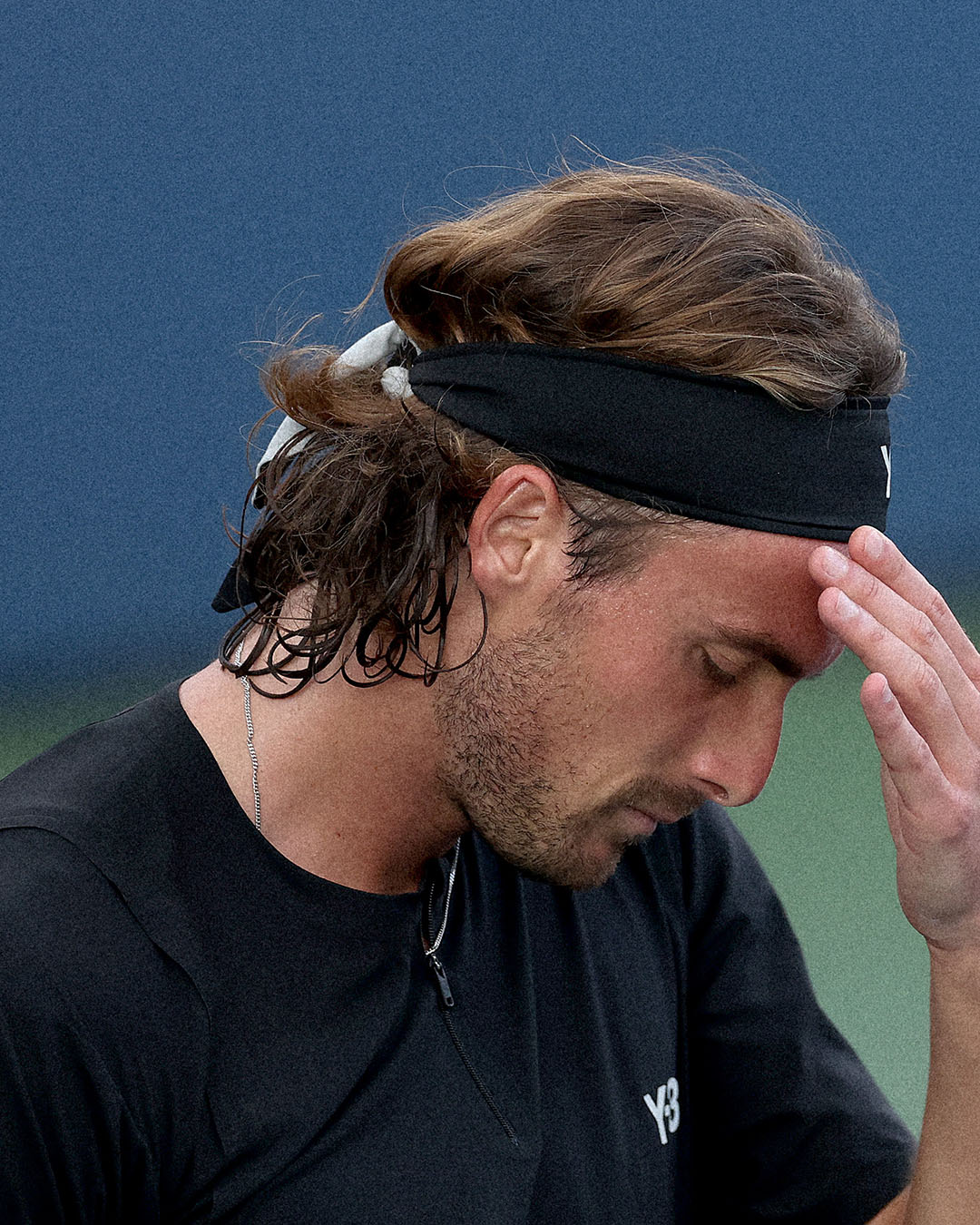

Oy Vey. "SadGen" stalwart, Stefanos Tsitsipas. // Getty

Oy vey. "SadGen" stalwart, Stefanos Tsitsipas. // Getty

In dark times, I turn to the past for comfort: When Daniil Medvedev was kicking Rafael Nadal’s ass through two and a half sets of the 2022 Australian Open final, fresh off winning the 2021 US Open, he looked like the future. A giant first serve and octopean court coverage seemed an ideal recipe to dominate the hard courts for the next half decade. Medvedev had disposed of Novak Djokovic in the previous major final without much trouble, and now the Serb was sitting out the AO thanks to a prolonged, surreal deportation saga. Who knew if he’d be able to recover? Another rival in Dominic Thiem destroyed his wrist hitting a forehand in 2021, and Nadal? Well, Medvedev was handling him just fine, up 6–2 7–6, 3–2 with three break points in hand. Medvedev would probably rack up six or seven of these majors, maybe more if he translated his prowess on cement to clay and grass. Stefanos Tsitsipas and Alexander Zverev could pounce on the crumbs he left behind.

Well, Nadal improbably came back to win that Australian Open final, then won Roland-Garros; Djokovic took over from there until 2024; Carlos Alcaraz won the two majors Djokovic didn’t and began sharing the Slams with Jannik Sinner instead once Novak began to fade. Polished, napalm-packed games shredded Medvedev’s peculiar, probing style. Djokovic employed the serve-and-volley against Medvedev to almost cruel effect, demonstrating the inherent weakness in Medvedev’s Mariana-Trench-deep return position for all to see in the process. These modern greats left no crumbs for Medvedev, much less anybody else. Daniil, still just 28 years old, is now the face of a doomed generation of ATP players.

To think that we once debated who among the NextGen would finish with the most majors, envisioning tallies deep in the single digits. Tsitsipas still has a bad backhand and now a bad back; his former coach Goran Ivanisevic was so critical of his charge that it seemed to torpedo the relationship. Zverev, the least sympathetic of the group, has long been reduced to lobbing excuses after early defeats and now conspiracy theories about court speed. Casper Ruud, three times a major finalist, doesn’t seem likely to make another and would rather play golf on grass than tennis. Frances Tiafoe pulled the plug on his season months early and is replacing his team.

The original LostGen of Grigor Dimitrov, Milos Raonic, and Kei Nishikori has already seen their window open and then slam shut; the group we once dubbed the NextGen is now SadGen.

Lately, the despair is visible in SadGen players’ demeanor. On his way out of his last several tournaments, Medvedev has raised hell upon the chair umpire. His seven-minute outburst during his first-round loss to Benjamin Bonzi at the US Open went instantly viral and was hilarious at times, but once the laughs faded you realized this was just a 28-year-old man throwing the most public tantrum possible. His cramp-induced retirement against Learner Tien in Beijing involved contentious discussions with both umpire and supervisor. And last week in Shanghai, as Arthur Rinderknech celebrated bouncing Medvedev out in the semifinals, Daniil was still griping with Mohamed Lahyani. Medvedev’s specific complaint was that Rinderknech had held up a hand, asking Medvedev to wait before the match point and (apparently) breaking his rhythm. But Medvedev had himself to blame more than anybody else—having saved one match point with a 128-mph second serve, he tried it again on the next one and missed badly. “Explain yourself,” Medvedev berated Lahyani after the match, as Rinderknech celebrated. Et tu, Daniil? A safe, spinny second serve was an option too. Medvedev just won the Almaty Open, a 250-level tournament, a much-needed victory but not one that seems likely to tame his temper the next time his game goes off the rails.

Tsitsipas, meanwhile, recently scheduled a series of tweets to send during his funereal loss to Sinner at the Six Kings Slam exhibition in Saudi Arabia. More alarmingly: His tweets are now accompanied by a distinctive note labeling them as “Ad.” Tsitsipas’ sometimes unattributed, sometimes bizarre philosophical musings have become monetized content. He and Medvedev, both major finalists inside the past three years, are having a good old existential crisis.

Though their grieving processes can prove cringeworthy, I sometimes think we hold SadGen players to too high a standard. The simple fact is that the all-time greats are just much better at tennis. Losing to them repeatedly over a decade-long span and then crashing out due to that fate strikes me as entirely natural, rather than a sign of crippling mental weakness. After the Cincinnati final, in which Sinner retired ill after five games against Alcaraz, a friend texted me that had Taylor Fritz done so instead, the tennis world would have jumped down his throat for being a disappointment. I agreed, then paused to ask myself why. Was it the manifestation of a desire for someone, anyone, to overcome their apparent limits and upset the status quo at the top of the game?

At Wimbledon, Fritz came closer than he ever had. Alcaraz beat him in a four-set semifinal but stared down two set points in the pivotal tiebreak that would have forced a decider if converted. A popular first instinct after Alcaraz reeled off four straight points to close the match, despite Fritz beginning each of them with either a precise first serve or a baseline-kissing return, was to criticize Fritz for not optimizing his aggressive forehands afforded to him by his good early work. In hindsight, I think this was silly. Taylor, as the underdog, hit wonderful shots on all four points, beneath stifling pressure to which his opponent was far more accustomed. To expect perfection from him after Alcaraz then returned those wonderful shots is simply not a realistic standard for Taylor Fritz—it’s a realistic standard for Carlos Alcaraz. (Alcaraz himself failed to meet that standard in the final, I suspect partly because Fritz made him use too much of his magic to survive here.)

Tennis results can feel frustratingly predetermined at the best of times. Even Djokovic, paragon of inevitability for most of his career, will surely never beat Sinner again. “It’s one of the best matchups we have,” Alcaraz claimed before Sinner predictably beat Djokovic in straight sets for the fourth straight time, at an exhibition in Saudi Arabia, facing all of one break point in the process. If true, that’s a dire landscape of rivalries. Few would blink an eye, though, if Djokovic retired right now. SadGen players will feasibly play for another decade, and all the way they’ll be hounded by the younger, more skilled New Two. I might cringe at Medvedev’s antics, but if the proposition in my own life were to work my butt off in the hopes of outdoing supertalented peers (unlikely) or capitalizing at a major in which both were injured (keep dreaming), I couldn’t vouch for my own sanity either.

None of this is especially conducive to an entertaining ATP Tour. Alcaraz-Sinner matches rarely miss, but if made to explain to a stranger why I dedicatedly follow a half of the sport that boasts all of one elite, competitive rivalry (and even here Alcaraz has won seven of the last eight), I worry I’d sound incoherent. Participating in this impossible game as a member of SadGen seems far worse than a dubious pastime, though: Einstein’s classic definition of insanity is also your job description. Perhaps there’s comfort in what you know, even if the familiar is something like misery.