An October Surprise

An October Surprise

An October Surprise

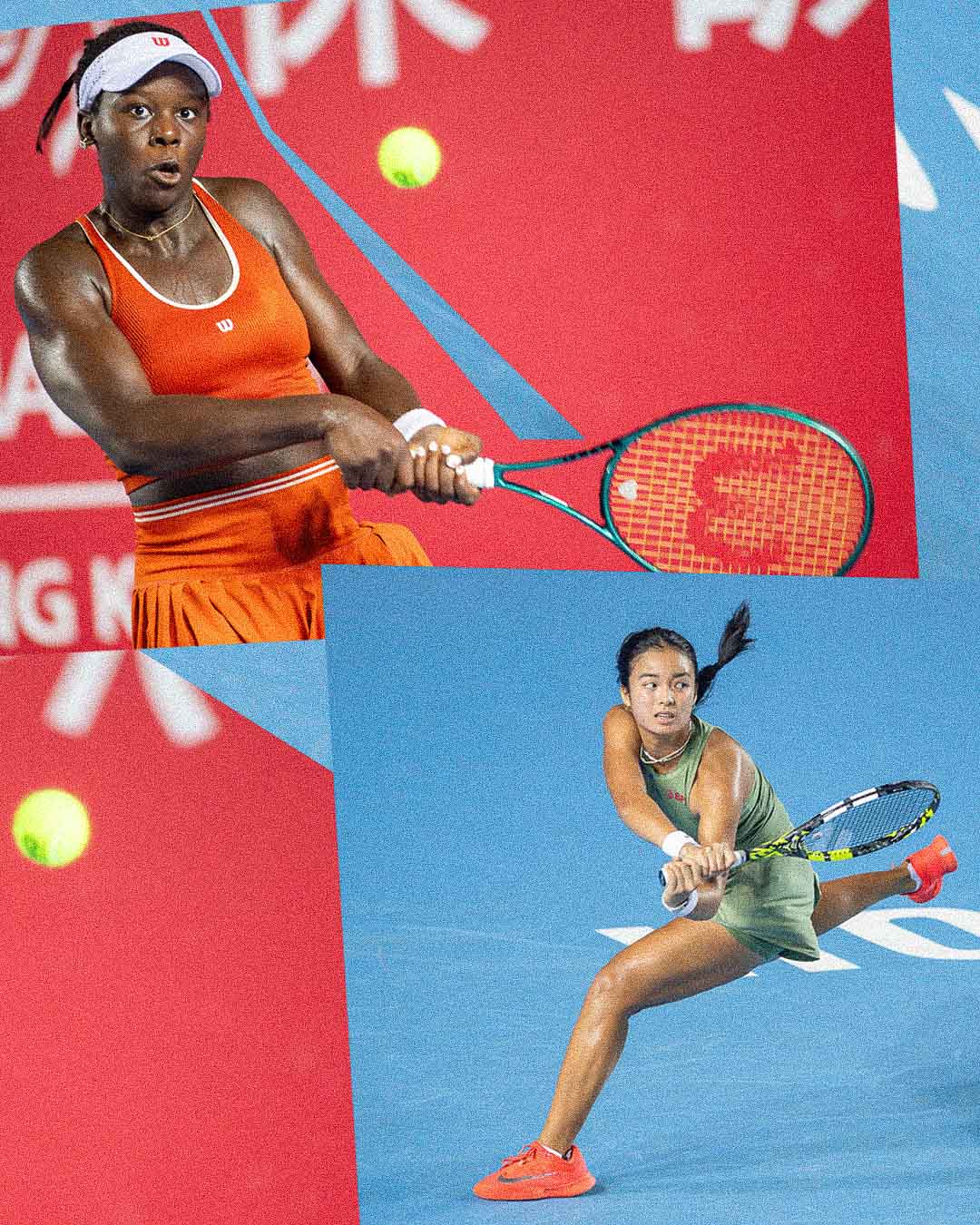

Nobody told Vicky Mboko and Alex Eala they should be phoning it in.

Nobody told Vicky Mboko and Alex Eala they should be phoning it in.

By Giri Nathan

October 31, 2025

Vicky Mboko and Alex Eala during their corker in Hong Kong. // Getty

Vicky Mboko and Alex Eala during their corker in Hong Kong. // Getty

Just like many professional tennis players, I don’t care all that much about the end of season, but I do love a good narrative coda. Victoria Mboko and Alex Eala were two of the WTA’s youngest and most thrilling breakout players in 2025, and on Thursday they battled in Hong Kong for the right to prolong that season just a little longer. Although Mboko, 19, and Eala, 20, are longtime friends who “get bubble tea together,” as the eventual victor explained after the match, they had never played each other at the pro level. At least they started this potential rivalry with a genuine classic.

Both players had similar triumphs this season, breaking out at 1000-level tournaments. They’d entered as wild cards with little experience and left them as known entities. Eala went first. In Miami, the then 19-year-old reached the semifinals by clearing three former Slam champs: Jelena Ostapenko, Madison Keys, and, notably, Iga Swiatek, who just two years prior had been the guest speaker at Eala’s graduation from the Rafa Nadal Academy. Most remarkable was the fact that the lefty Eala was beating all these players in spite of her rather vulnerable serve, all on the strength of her ground strokes, struck hard from right on top of the baseline. She nearly beat Jessica Pegula in the semifinals, too. That was the high point of the season—it’d be a high point of many careers—but Eala also went on to pick up a WTA 250 runner-up trophy in Eastbourne and a WTA 125 title in Guadalajara, and, at the US Open, she became the first player from the Philippines ever to win a main-draw match at the majors.

For Mboko, there had been some sparks beforehand. A three-setter in Rome against Coco Gauff raised many eyebrows, mine included. But it all came together all at once, in Montreal, in front of the Canadian home crowds. Like her friend, she also dismissed a horde of Slam champs: Sofia Kenin, Coco Gauff, Elena Rybakina, and Naomi Osaka. But unlike Eala, Mboko won the whole title, then just 18 years old. Her tennis was mysteriously well-rounded, blending power, counterpunching, and great hands, but I mainly remember this title as one of the most startling examples of mental fortitude I’d seen in a young player. So many comeback wins, and so many cases where she looked like the more poised one in the face of opponents years older and more accomplished. Incredibly, her Montreal win meant she’d be seeded at the upcoming US Open, despite starting the season outside the top 300. She seemed like a new fixture on tour. In reality, these things are always more complicated. She went on to lose four consecutive first-round matches after her title.

But by the time they met at the WTA 250 in Hong Kong on Thursday, Mboko had stabilized again. Heading into the match, she was ranked No. 21 to Eala’s No. 51. By the time they’d split sets, they looked dead even, and the rally level was getting a little absurd.

My working theory is that the most thrilling tennis matches involve future stars whose serves are still quite dubious. No service hold is taken for granted. And you have no idea what shot they might opt for next, because their ambitions sometimes outpace their present abilities. That roughly describes the back half of this match. There were five breaks of serve in the deciding set. First Eala moved ahead. Once her legs tired, she closed down the net to finish points and excelled there, seizing a 4–1 lead. The Hong Kong crowd thrummed for her. But Mboko, the comeback artist, won every remaining game in the match. Returning at 4–4, 40–30, she clocked a backhand return winner right off the baseline, and that was the last time her victory was ever in question. Mboko won, 3–6, 6–3, 6–4, and the two hugged, with unusual joy. It was a match fought with genuine energy and minimal cynicism between two players who did not seem to accept the notion that October was a time for coasting and burnout, and instead saw their entire careers unfurling ahead of them. Pretty decent recipe for tennis, as it turns out.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Killer of Giants

Killer of Giants

Killer of Giants

Learner Tien goes to the head of the class.

Learner Tien goes to the head of the class.

By Giri Nathan

October 3, 2025

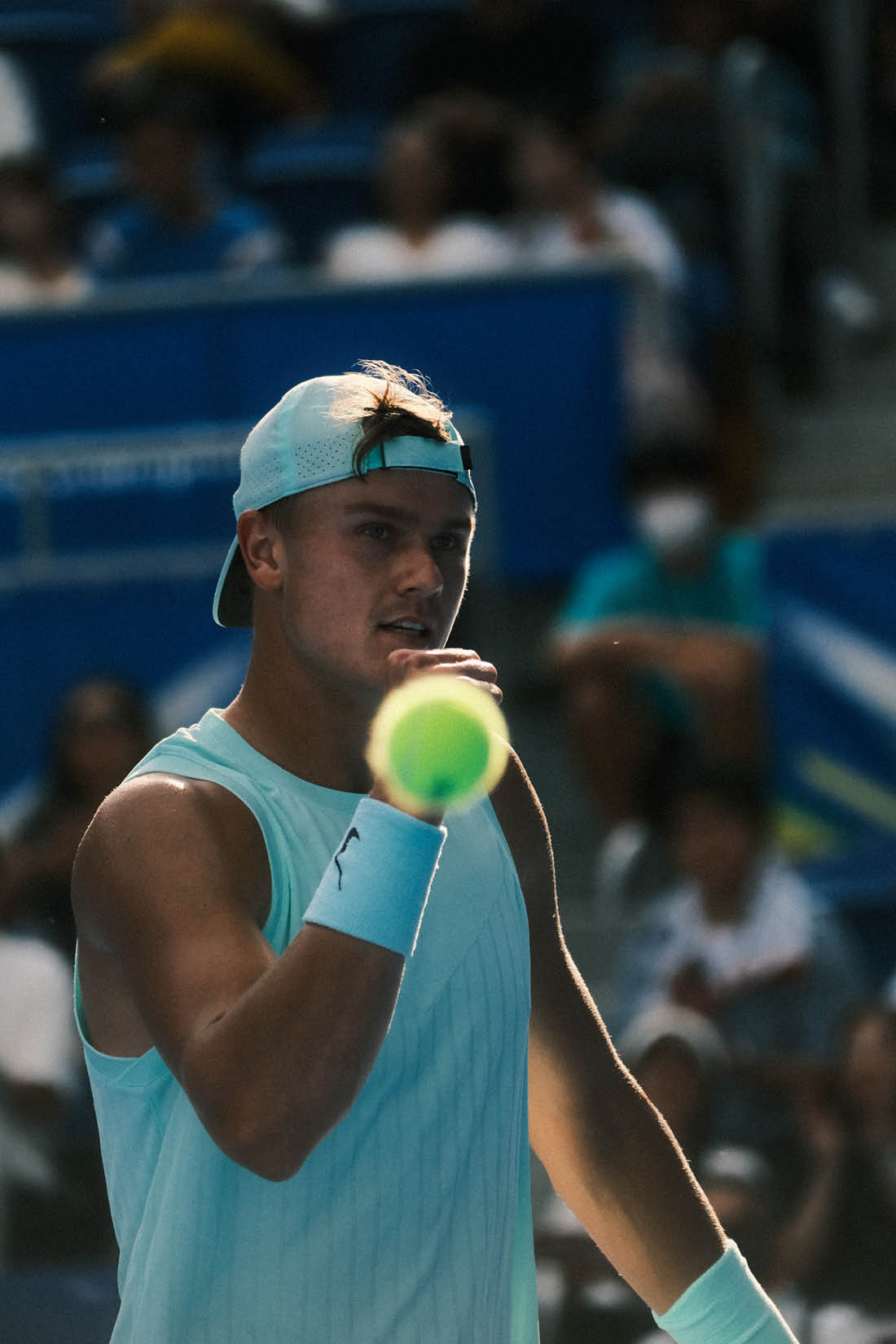

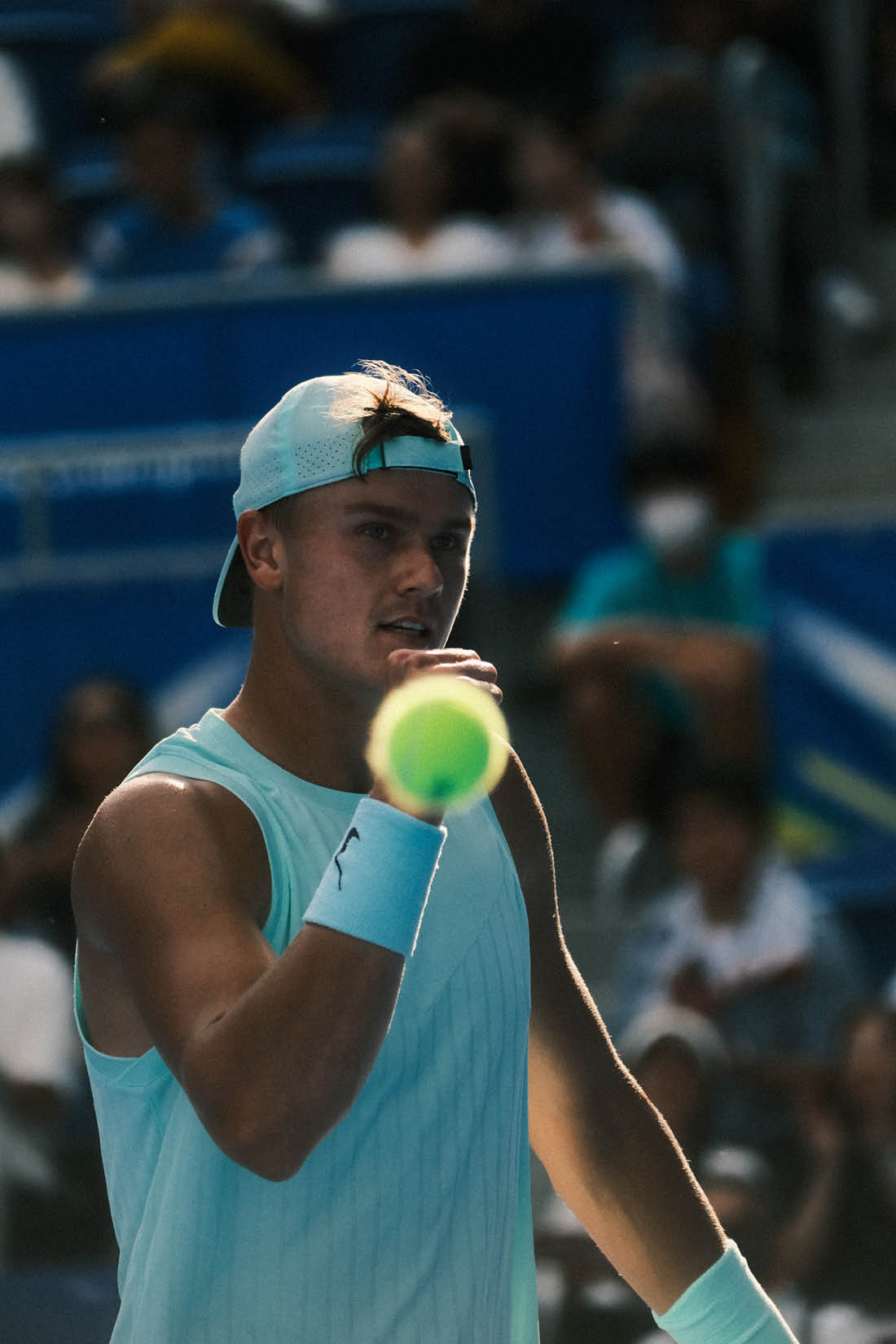

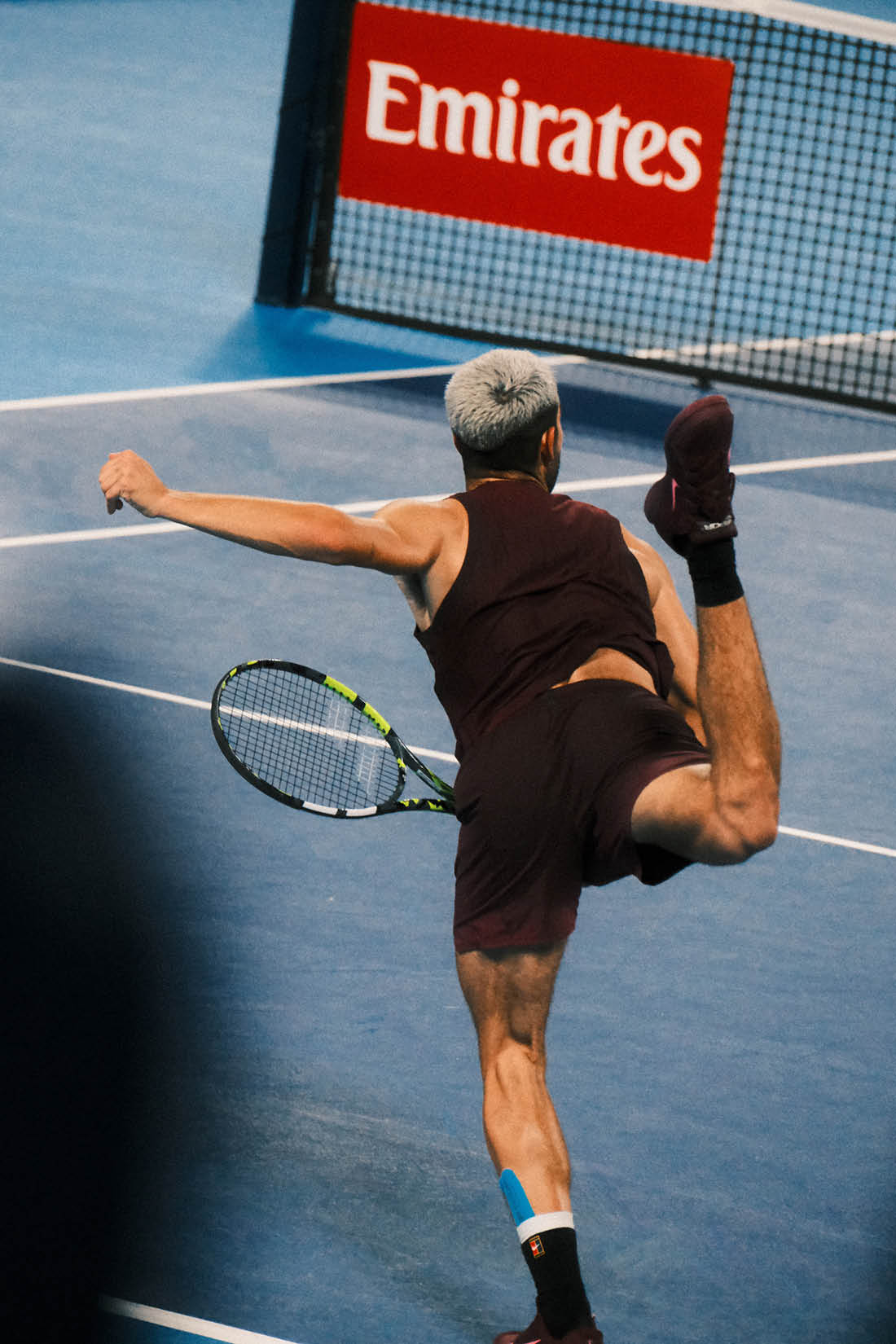

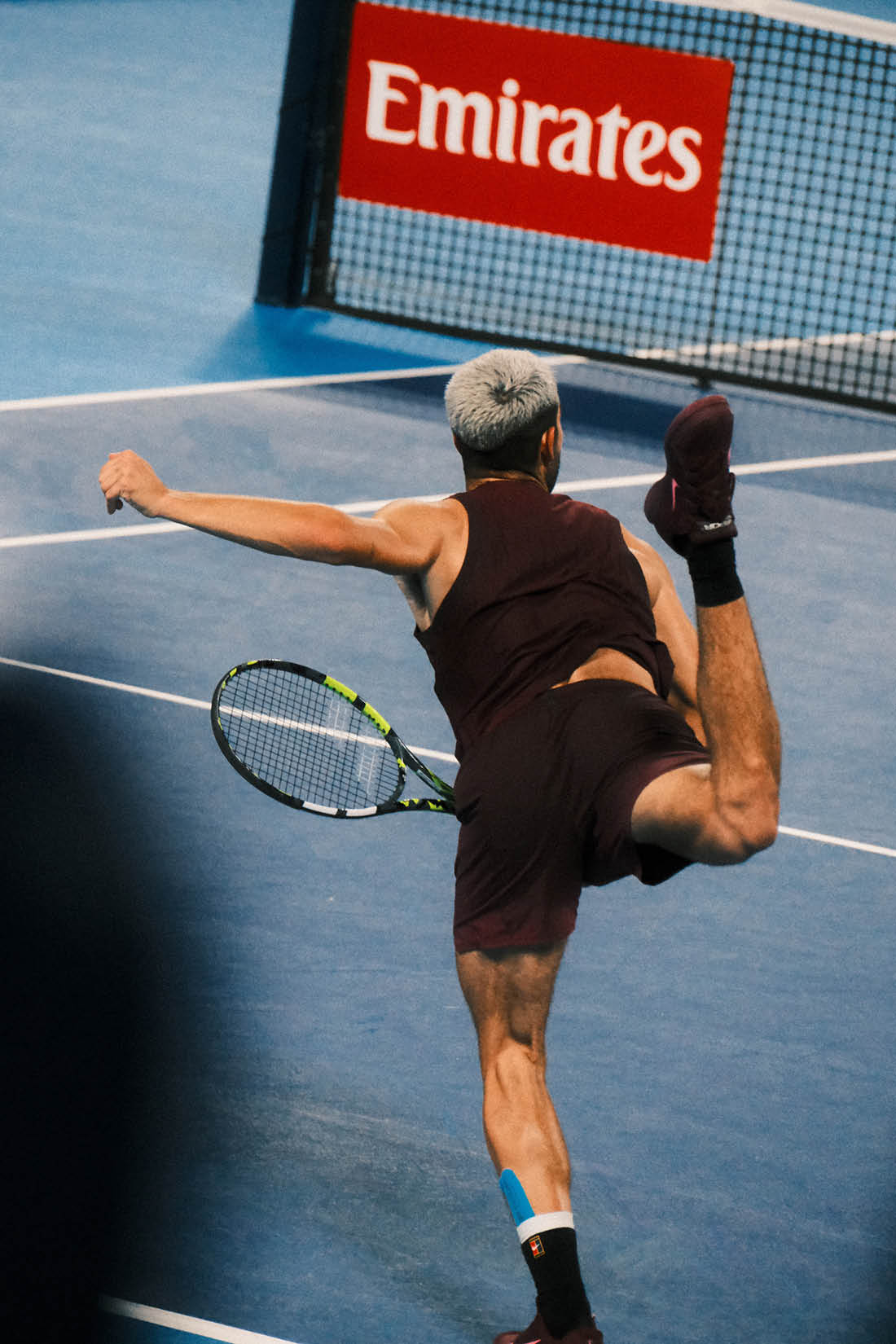

After capturing a plate in Beijing, Learner Tien has an appetite for more. // Getty

After capturing a plate in Beijing, Learner Tien has an appetite for more. // Getty

As he winds down his rookie season, the 19-year-old Learner Tien has compiled an intriguing résumé. What you see in Tien depends on which frame you choose. Start broad, then zoom in, and things get weirder as you go. When playing against all top 50 players this year, Tien is 9–14. Nothing earth-shattering, but very respectable for a teenager making the leap from the Challengers to the ATP level. What if we filter those results more? When playing against top 20 players this year, Tien’s record is 6–5. And then what if we limit to just those opponents ranked in the top 10? A blistering 5–3 record. This kid from Irvine, Calif., has accumulated more top 10 wins this season than anyone besides Carlos Alcaraz or Jannik Sinner. While Tien’s still working on week-to-week consistency against the tour’s rank and file, he seems to relish every chance to play against the very best players alive. And he’s beating them with one of the most oddly satisfying play styles you’ll see—a mix of sweet feel, sharp angles, lefty guile, and cool temperament.

This week in Beijing, Tien became the third-youngest ATP finalist of the season, behind fellow teen phenoms Jakub Mensik and Joao Fonseca, but on the right day he looks like he has more potential than either of those more-hyped peers. Bolstering his rep as a giant-killer, Tien moved through a brutal draw to get to the final of this 500 event: Francisco Cerundolo, Flavio Cobolli, Lorenzo Musetti, and Daniil Medvedev, though admittedly those last two opponents withdrew from third sets with injury, after Tien had already twisted the match in his favor. By the time Tien finished the championship match, he had gained membership in one of the fastest-growing tennis clubs in the world: people who have been mauled in straight sets by Jannik Sinner on a hard court. But everything that led up to that match was tremendously promising for Tien, who has just moved inside the top 40 and who, just a few weeks ago, hired as coach the greatest-ever Asian-American tennis player from Southern California: Michael Chang.

Just as it went with his coach, Tien’s stature is a common source of skepticism. At 5 foot 11 he lacks the long levers seen in most players at the top of the contemporary game. But the way that Tien is sometimes described, you’d think he was a modern-day Gilles Simon, massaging the ball around the court and playing a purely attritional game. Tien does relish the occasional long rally, but Simon is not at all what I see in him. He doesn’t have the face-melting, point-ending power of Sincaraz—a quality that his fellow teen Fonseca does, in fact, possess—but Tien loads up his ground strokes with plenty of pace and spin. To my eye, he’s got much more pop on his shots than he did this time last year, which is not all that surprising, given that he’s still growing up. (One measure of his youth is the fact that he has said he grew up watching Alcaraz, a quote that instantly reduced me to a heap of dust.)

What I’m most struck by is how mature his baseline game already is. He perturbs opponents of the highest caliber. Tien’s open-stance forehand I find impossible to read, and he seems so nonchalant when changing the direction of a rally. He opens up surprising angles early and often. Whenever he finds an opening, he ends points at the net with soft hands, which might portend a future that’s more all-court than counterpuncher. Perhaps these skills don’t inspire as much buzz as the quantifiable, raw power of Fonseca’s ball-striking, but it works all the same. (Right now, it’s actually working better; Tien just moved past Fonseca in the rankings.) It’s a savvy, supple baseline game that holds up well against big hitters—with Sinner the obvious and understandable exception. A year from now, I bet I’ll be favoring Tien over most opponents when caught in a neutral rally on a hard court. For evidence, just talk to Sascha Zverev, Daniil Medvedev, and Andrey Rublev, all of whom have lost to the new kid this season. (And if you do talk to them, you will hear Medvedev’s outstanding pronunciation of Le-ARN-er, which he has rendered somehow Italian.)

But it’s difficult to claw into the top 10 while needing to win every point from that neutral rally. Cheap and easy points make ATP life much more pleasant. As impressive as Tien’s ground strokes are, his serve is not yet doing him many favors. Often he’s spinning the ball in to get the point started. His coach is aware of this central deficit in Tien’s game and has said that they’re working on it. I recently asked the analyst Gill Gross about some great recent servers who are under six feet tall. It’s not the easiest list to populate, but we agreed that Mattia Bellucci, the 24-year-old Italian, is one intriguing outlier who can crack 130 mph despite standing just 5 foot 9. Tien, who already hits his spots quite well, has room for technical improvements on his serve that could squeeze out some more mph, according to Gross. It’s a testament to Tien’s skill as a returner and baseliner that he’s gotten this far on tour with his current delivery. He’s on the cusp of getting seeded at the Slams. Even a perfectly average serve would take him up another notch again. Leave it to Chang and his new protégé to prove that modest height is no death sentence in this sport.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Postcard from Tokyo

Postcard from Tokyo

Postcard from Tokyo

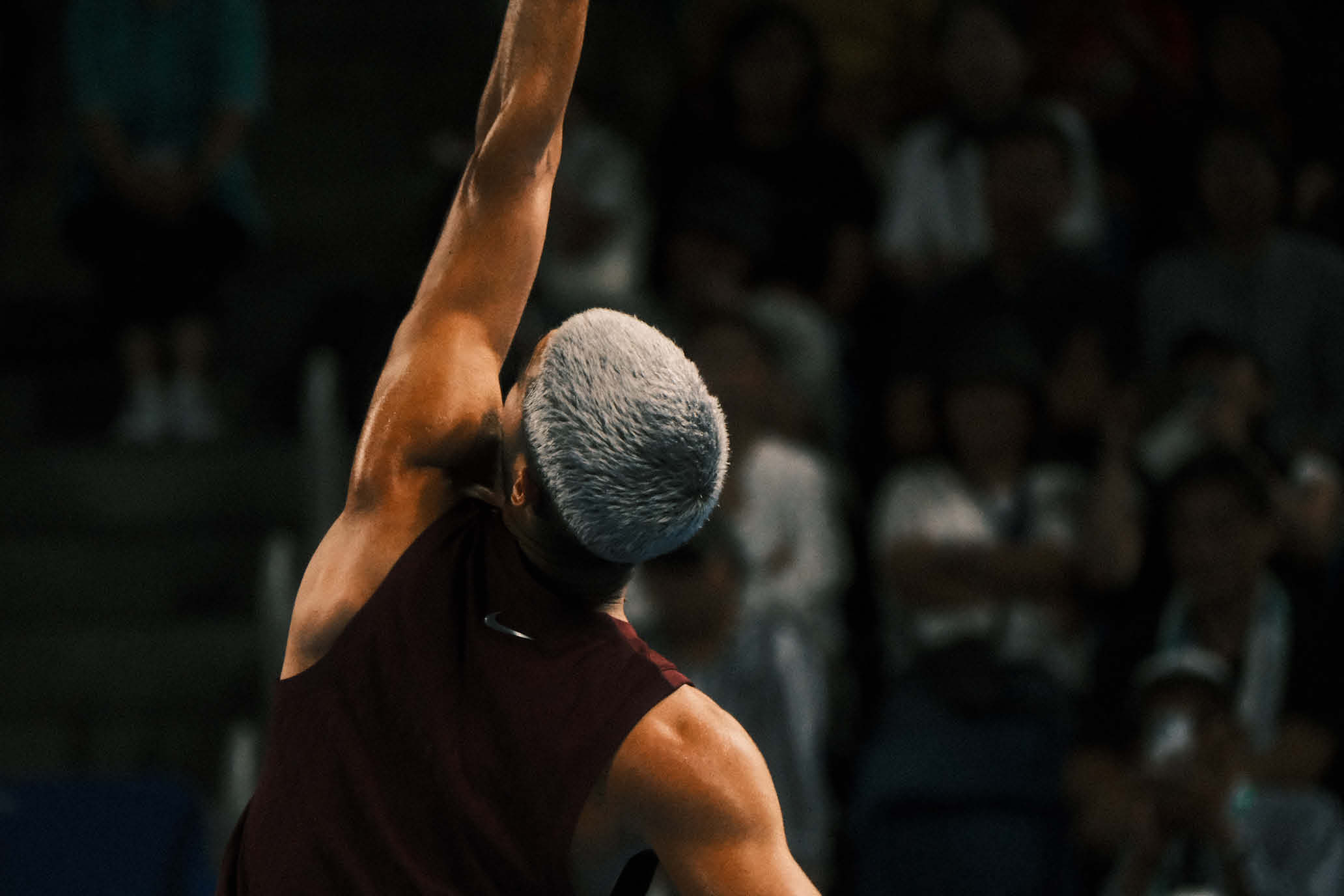

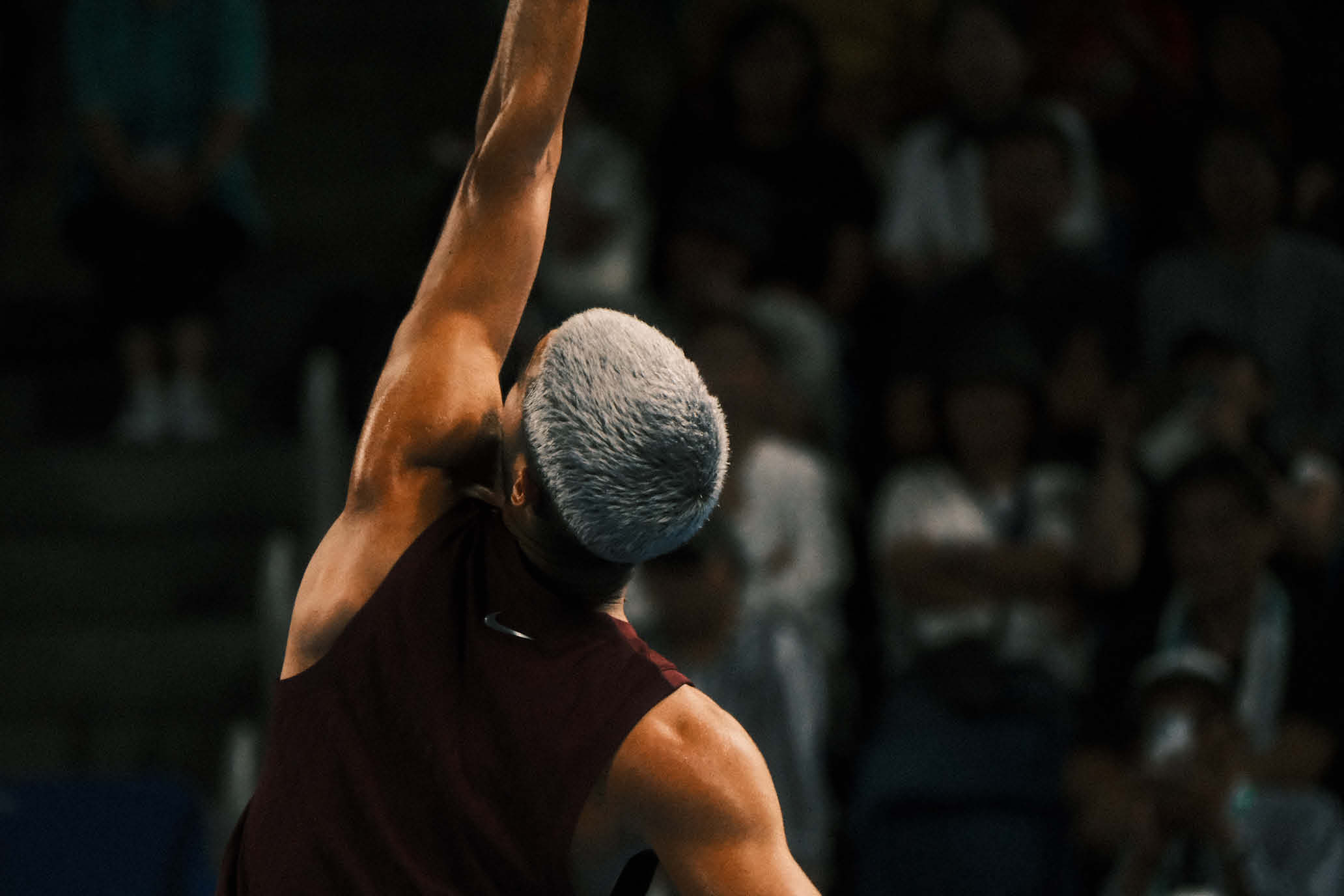

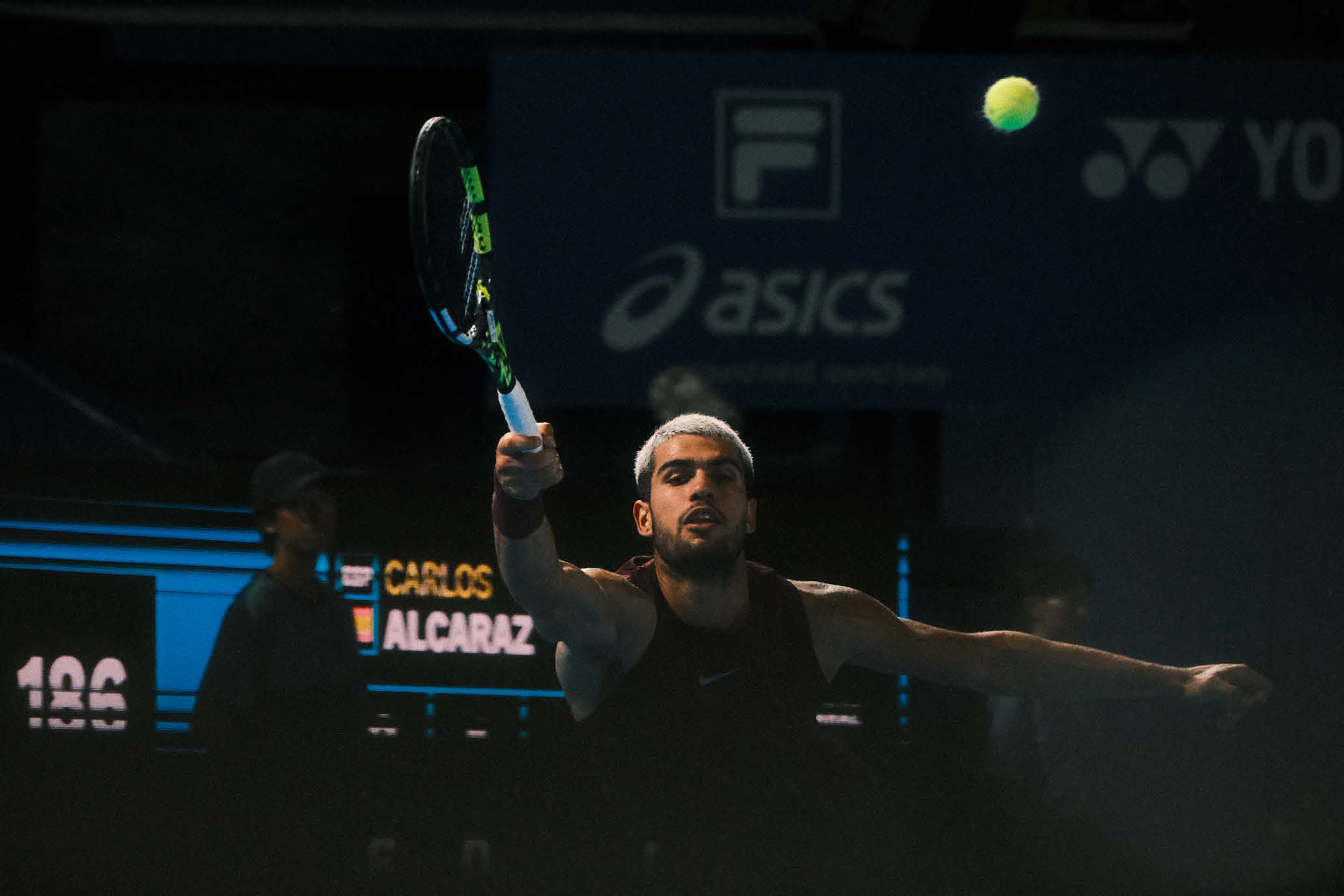

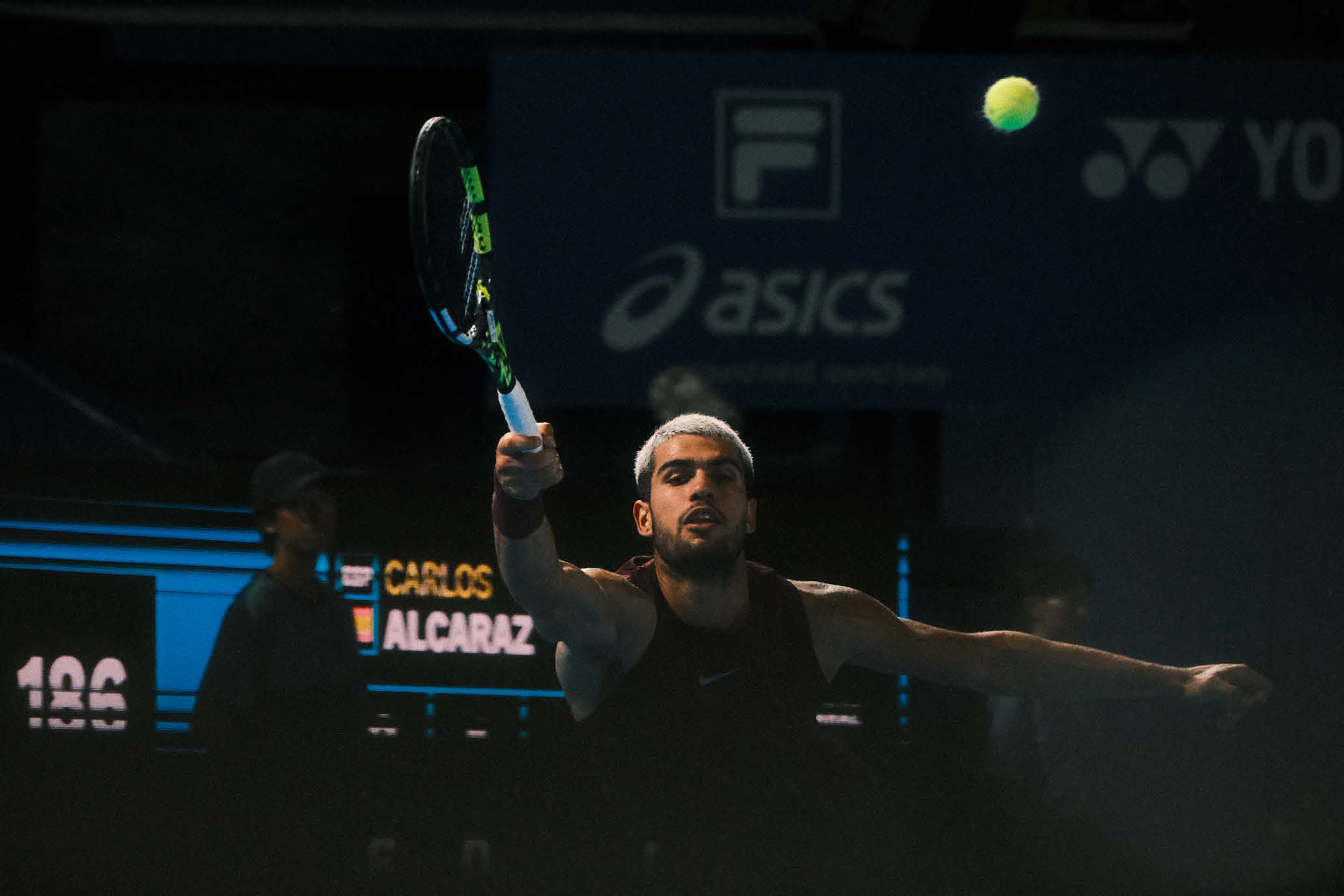

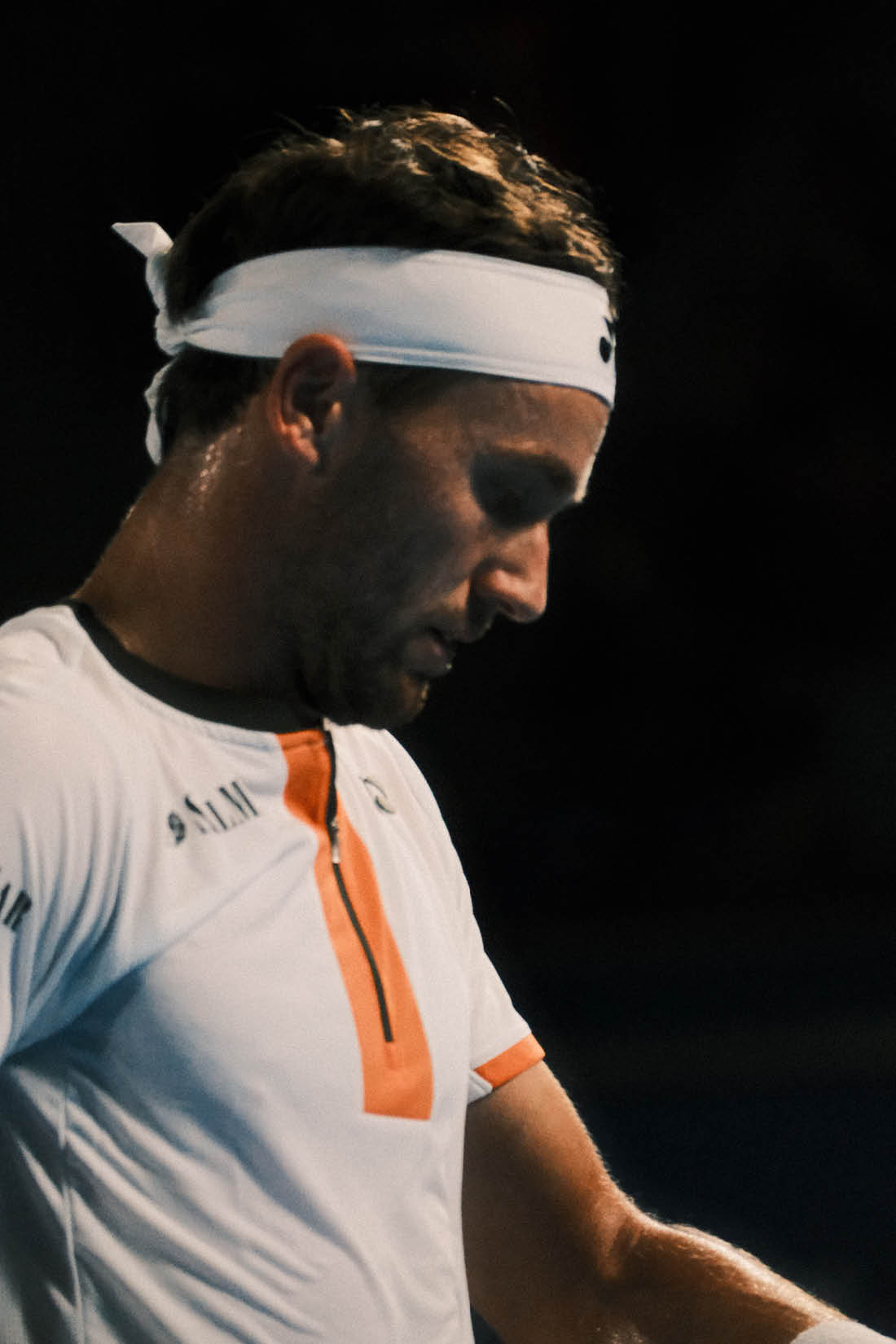

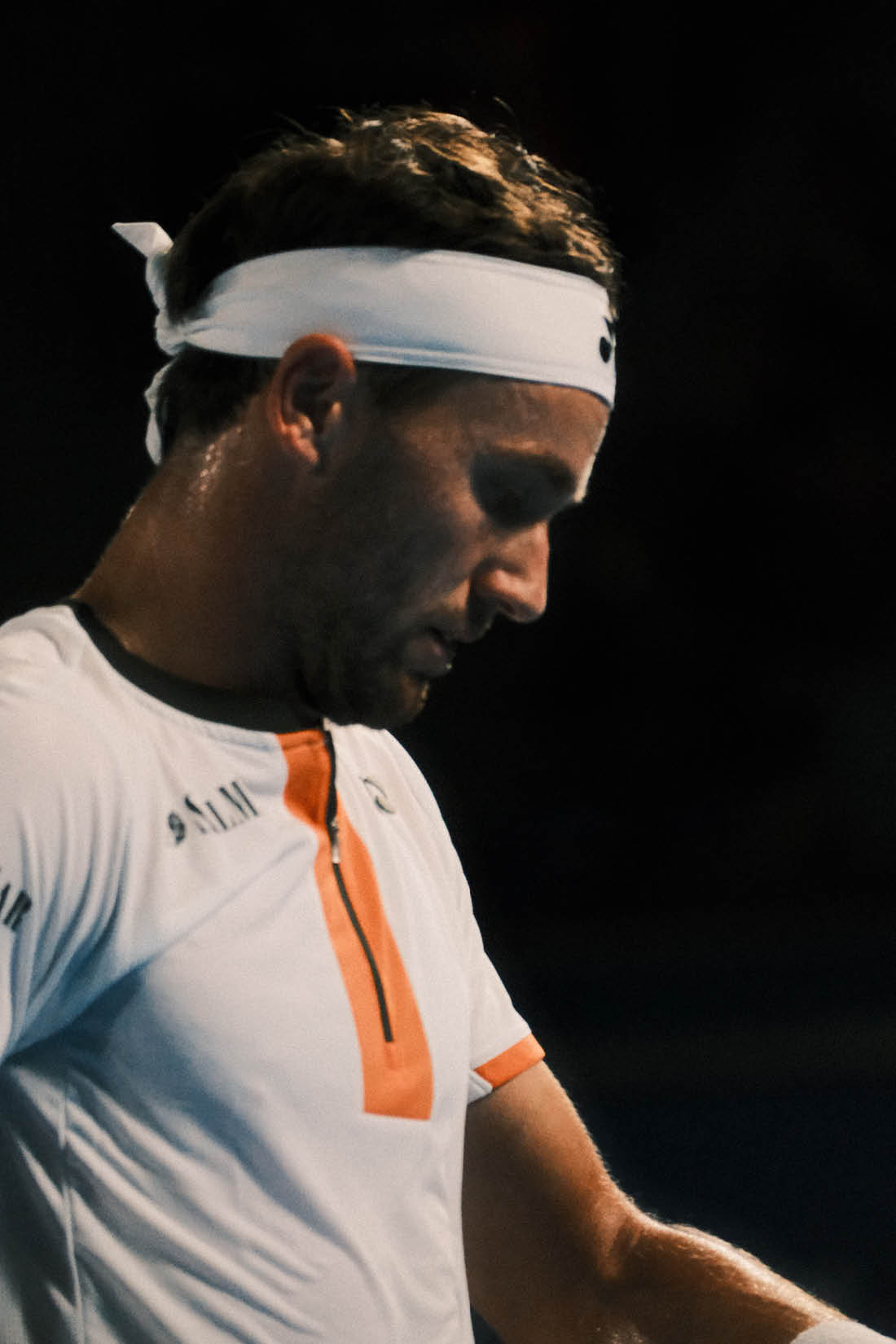

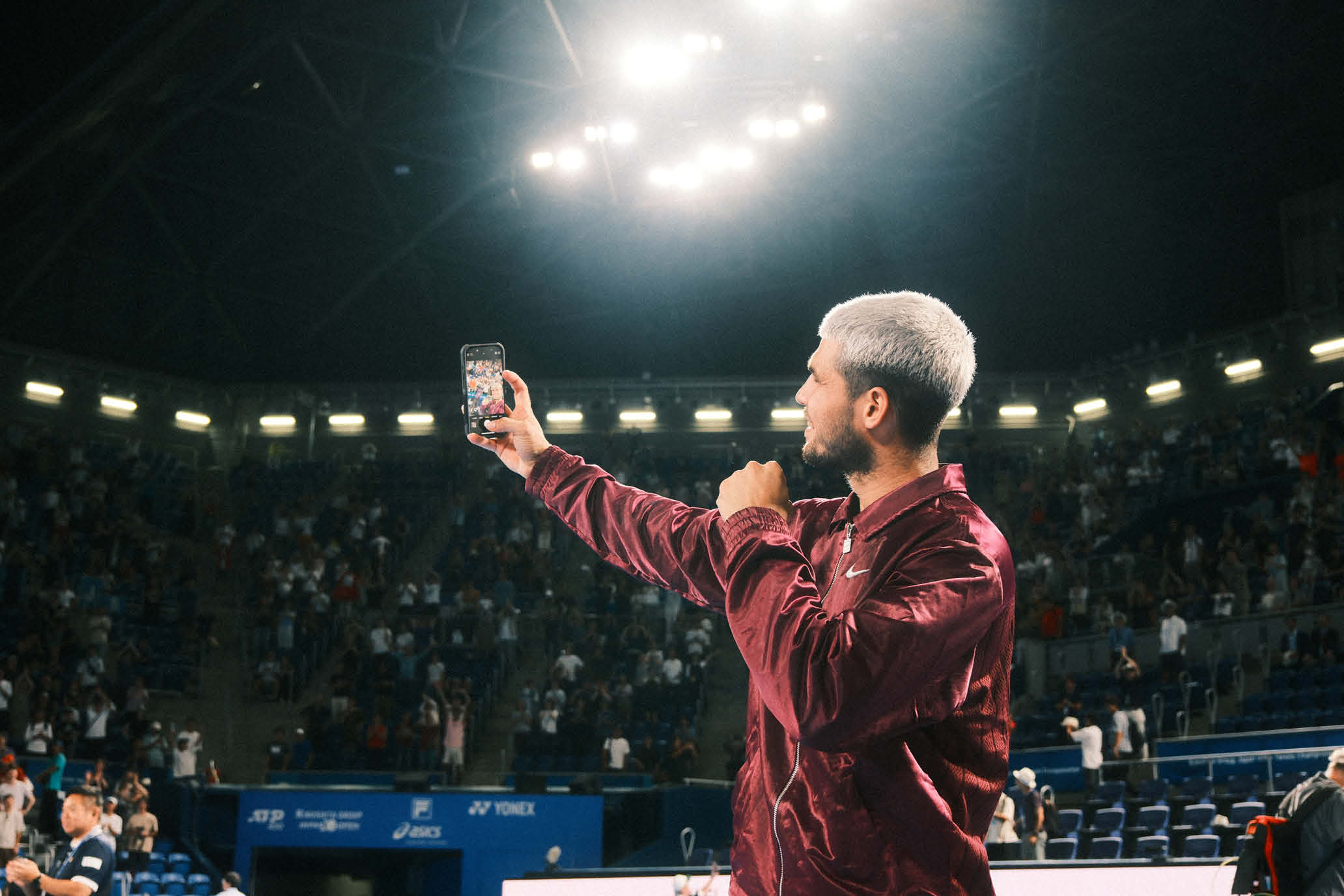

Moody vibes under Tokyo skies as Carlos Alcaraz electrifies passionate tennis fans at the Japan Open.

Moody vibes under Tokyo skies as Carlos Alcaraz electrifies passionate tennis fans at the Japan Open.

Photography by David Bartholow

SIGN UP — YOU'RE ONLY AS GOOD AS YOUR SECOND SERVE.

Finish Line

Finish Line

Finish Line

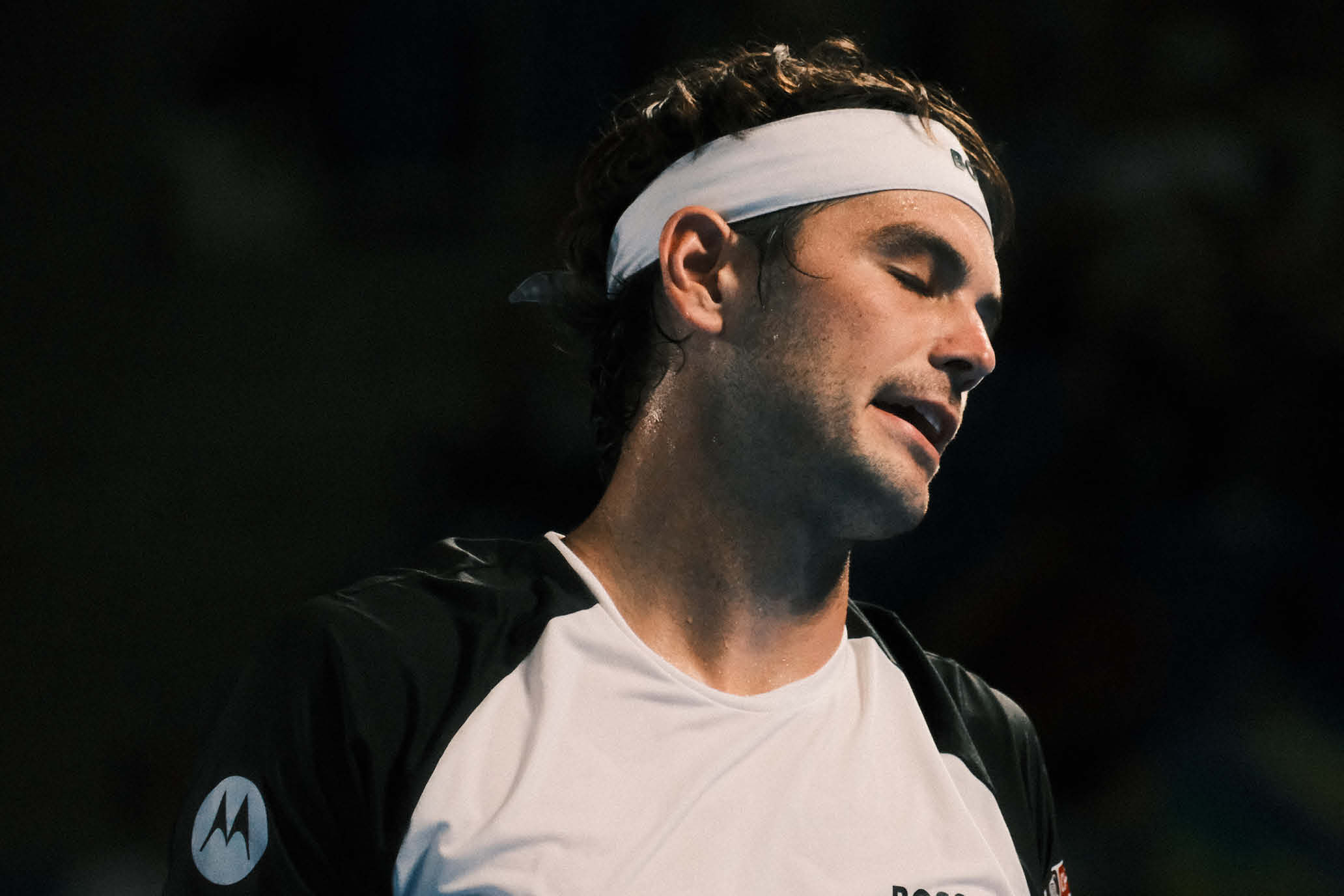

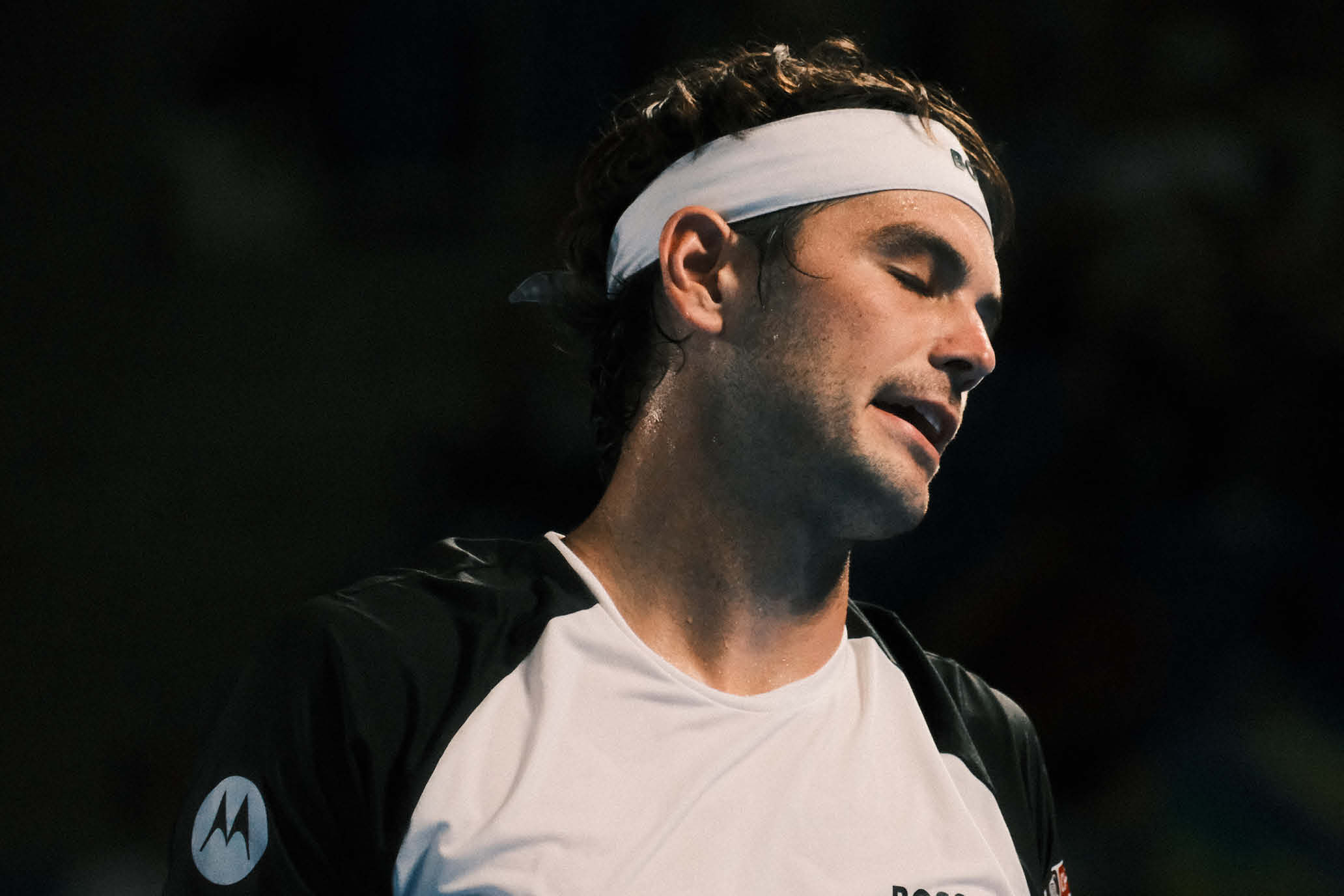

Jannik Sinner and Carlos Alcaraz vie for the year-end ranking of No. 1 in the world.

Jannik Sinner and Carlos Alcaraz vie for the year-end ranking of No. 1 in the world.

By Simon Cambers

September 23, 2025

Jannik Sinner celebrates a victory, and a year-end No. 1 ranking inTurin last year. // Getty

Jannik Sinner celebrates a victory, and a year-end No. 1 ranking inTurin last year. // Getty

Roger Federer used to begin every year with two main goals: to win his beloved Wimbledon and to finish the year ranked world No 1. Lofty goals for most, realistic aims for a man who ended up winning Wimbledon eight times, second only to Martina Navratilova, and who topped the year-end rankings five times.

Until the establishment of the ATP rankings in August 1973, the world rankings were an informal affair, decided by national associations, Tours, and—it hardly seems possible to imagine now—a small group of revered journalists. Not the most objective of arrangements.

While the old system was a constant source of argument, the new rankings held immediate credibility and prestige, providing players with a new goal that really meant something. Finishing the year ranked No. 1 was indisputable proof of who was the best player of that year. Ilie Nastase was the first man to earn the honor, in 1973, and only 18 other men have ever managed it, an elite band.

The race to end the year on top has seen many players make superhuman efforts, crisscrossing the world in the chase, knowing that their place in history would be assured if they could be No. 1 when the year ended. Take Pete Sampras. The American finished as world No. 1 for six straight years in the 1990s, an all the more remarkable statistic when you remember that he picked up very few points on clay. In 1998, he was so desperate to finish No. 1 for the sixth year in a row that he played six events between the U.S. Open and the season-ending ATP World Championships, as it was called then, edging out Marcelo Rios, the talented Chilean, to stay top dog.

“To get to No. 1 is one thing; but to stay there is another thing,” Sampras said at the time, having clinched the year-end ranking at the ATP World Championships in Hanover when Rios, exhausted and injured, pulled out before his first match. “It’s twice as hard. To have stayed on top for most of my career is a little overwhelming. You see many players in the past have not handled the pressure or not enjoyed it. I’m very comfortable being No. 1, and that helps.”

Novak Djokovic holds the record for the most years at No. 1 overall, with eight, but no one has come close to matching Sampras’ run of six on the bounce. I remember how physically and emotionally tired he was when he first chatted to the media in Hanover in 1998—the first time I covered the season-ending event myself—but the effort was worth it as he set a record that he feels may never be broken.

Andy Murray followed Sampras’ example when he ended the year ranked No. 1—for the first and only time—in 2016, winning five titles in a row to pip Djokovic for the honor, sealing the deal when he beat him in the final. Murray’s hip gave out midway through the following year, but even now he will say that finishing No. 1 meant everything. John McEnroe, who managed it four times, always said it was validation of a whole year’s results, showing, without doubt, who was the best.

In this era of instant gratification, it’s somehow reassuring that today’s top players also see ending the year at No. 1 as something worth the effort. Carlos Alcaraz’s victory over Jannik Sinner in the U.S. Open final gave him a commanding lead over the Italian going into the Asian swing of events, but there is still some work to be done if he is to become just the 11th man to finish a year at No. 1 more than once, having done so for the first time in 2022, after his breakthrough Slam win in New York.

It would be no surprise, though, should Sinner end the season on a charge. The fact that the ATP Finals are again held on home soil in Turin this year is an obvious incentive for him to finish the year strong, and the 24-year-old, who took his Grand Slam tally to four in 2025 thanks to wins in Melbourne and at Wimbledon, remembers the “special feeling” he experienced when finishing No. 1 for the first time at the end of 2024.

Providing Alcaraz stays healthy, it will take a herculean effort for Sinner to overhaul the almost 2,600-point lead the Spaniard had in the ATP Race—the calendar-year standings—going into this week’s events (Sinner is in Beijing, while Alcaraz is in Tokyo).

But Sinner showed last year just how good he is indoors, winning in Shanghai and then going unbeaten as he won the ATP Finals in Turin, picking up a combined 2,500 points in the process. Alcaraz won in Beijing last year—beating Sinner in the final—but if the Italian can cut the lead by winning again in Shanghai the following week, then anything’s possible.

Neither man is currently scheduled to play between then and the last Masters 1000 event of the year, the Rolex Paris Masters at the end of October, although even that could change if one or the other man feels he needs to add an event to chase more points.

Both players won two Slams apiece in 2025, and both are clearly showing signs of fatigue, but the lure of year-end No. 1 keeps them going. What happens in the Asian swing is likely to decide who ends up on top.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

September Song

September Song

September Song

The Laver Cup is about as entertaining as tennis can get in post-US Open.

The Laver Cup is about as entertaining as tennis can get in post-US Open.

By Giri Nathan

September 23, 2025

Taylor Fritz had perhaps the best weekend on the gray, slow hard court at the Laver Cup in San Francisco. // Getty

Taylor Fritz had perhaps the best weekend on the gray, slow hard court at the Laver Cup in San Francisco. // Getty

The Laver Cup wrapped up its eighth iteration. I think I can conclusively admit that they’ve hit on something good. Even the first iteration in 2017, which had some of the bluster and silliness of pro wrestling, was already entertaining to me. Then in 2022, Roger Federer chose to retire at the Laver Cup—because his management company co-owns it—burning a classic afterimage on that gray court. Now I’m so bought that, even though I often forget this event exists, I always lock in when it does reappear on my TV. After the long days of the U.S. Open I often don’t want to look at a tennis ball for weeks; these matches won me back. It’s about as entertaining as tennis can get in late September.

A reason for all that is that the players are actually trying. Is the Laver Cup an exhibition? It has the official stamp of the ATP, but that isn’t everything. Over at Bounces, Ben Rothenberg has written up a satisfyingly thorough breakdown of tennis exhibitions, applying lots of different criteria. In my own head, I think I had been operating under a softer standard: Do the results of the tournament tell you anything of enduring value about the players, and the careers going forward? Some exhibitions are played at about 30 percent effort, and the run of the match is worked out ahead of time; I find that stuff mind-numbingly dull, and I can barely stay seated to watch it. At the Laver Cup, however, the tennis feels real enough that I even find myself changing my opinion about certain players.

For example: Were you guys too quick to terminate the hype on 19-year-old Joao Fonseca? Watching him beat Flavio Cobolli in straight sets, I was reminded what a freakishly good ball-striker he is. He was treated like a prodigy on the Sincaraz trajectory, his third-round run in Miami set expectations high for the summer, and he made the third round at Roland-Garros. While he didn’t pull off many more splashy results, there were still some highly competitive, narrow losses against players like Tommy Paul and Taylor Fritz. If you were expecting top 20 by the end of the season, then sure, it’s disappointing, but No. 42. I think Joao’s biggest deficit, compared with 19-year-old Carlos or Jannik, is movement—he doesn’t fly in and out of the corners like those guys did—and I’m awaiting the offseason training block that solidifies his physical foundation. But he’s learning. Whenever Fonseca was interviewed at the Laver Cup, he talked about how much he was absorbing from his teammates.

That is one cool aspect of the tournament: transfer of wisdom. Some of it is coming from the coaches. As someone who was born after Yannick Noah’s playing career, and spent many more hours watching his son play basketball, I’m deepening my appreciation of one of the coolest dudes ever to walk a tennis court. Andre Agassi’s recent, drastic turn toward the spotlight has revealed him as perhaps the world’s best analytical tennis talker. But there’s also a lot of horizontal exchange among the players. As Federer pointed out in an interview with The Athletic, it’s the one time of the year where you can ask your teammates nuts-and-bolts tennis questions and they won’t be as cagey about giving up an edge, since you’re all on the same team trying to win the same $250,000-a-head prize. It’s funny to see Sascha Zverev, navigating a very tense match, brushing off Carlos Alcaraz and specifically shouting for Casper Ruud to tell him where to stand on second-serve returns. That’s not a dynamic you see often in this solitary game.

Zverev would go on to lose that match to Taylor Fritz, who secured the win for Team World over Team Europe and probably had the best weekend of anyone. On Saturday he beat Carlos Alcaraz in straight sets, and while I’m sure he would’ve rather taken that win anywhere but Laver Cup, it will count on the official ATP ledger, updating their head-to-head to 1–3. He maintained a clear vision of what he wanted to do on court—increase the pace on the rally balls, strike early and often—and never wavered. Fritz’s great play coincided with a roughly biannual bad forehand day for Alcaraz. The best ground stroke on the men’s tour wasn’t finding its mark, but that’s also because the man on the other side of the court was playing arguably his best match of the season.

Fritz remarked afterward that these were tricky conditions for his matchup against Alcaraz. The gray Laver Cup hard courts are gritty and slow; those Wilson balls got roughed up and puffed up to grapefruit size. (Sidenote: Many fine rallies on this court. Give us more hard courts like these! Or take away the second serve.) “I felt like it was going to be very hard on a surface like this for me to hurt him. I felt like it was going to be very easy for him to put me out of position,” Fritz said. But his strategy still worked perfectly. It’s enough to make you wonder if Fritz, a former Indian Wells champ, might in fact be a slow hard-court specialist. Perhaps he gets fewer aces than he otherwise would, but he still has power to hit through the court, and this vastly improved but still limited lateral mover can retrieve more balls than he would otherwise. When he has a bit more time on the ball, he has phenomenal rally tolerance.

“I’m so proud of Fritzy, and I hope he realizes what he’s capable of,” said euphoric coach Agassi after the upset. This season Fritz had lost a very competitive Wimbledon semifinal against Alcaraz; does this win show him a way forward? I’ve already consigned 2026 majors to Sincaraz dominance, but maybe he can keep things more interesting. Even the fact that I’m speculating about this is a testament to the Laver Cup; rather than an isolated exhibition, it seems continuous with the fabric of pro tennis.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Bjorn Free

Bjorn Free

Bjorn Free

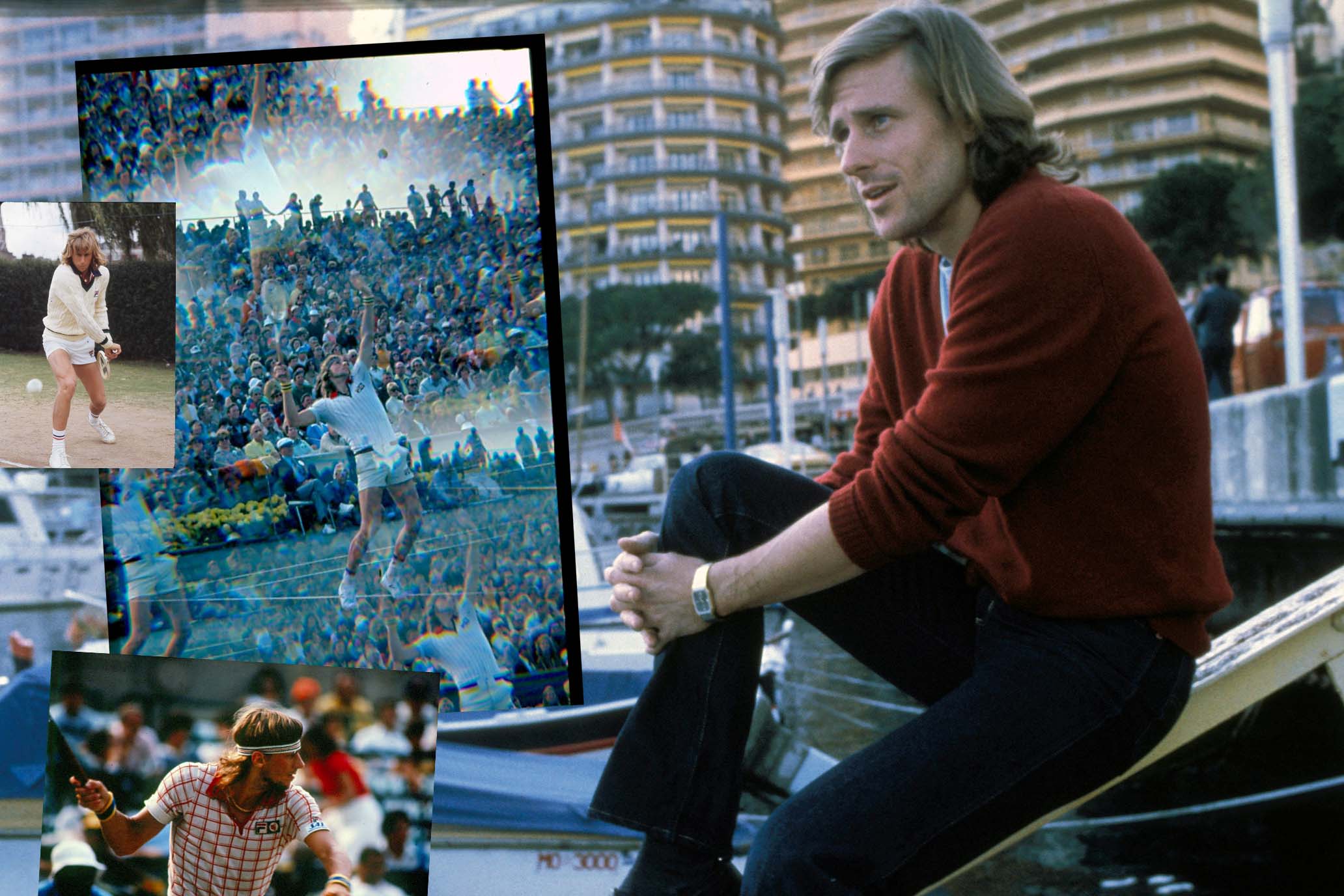

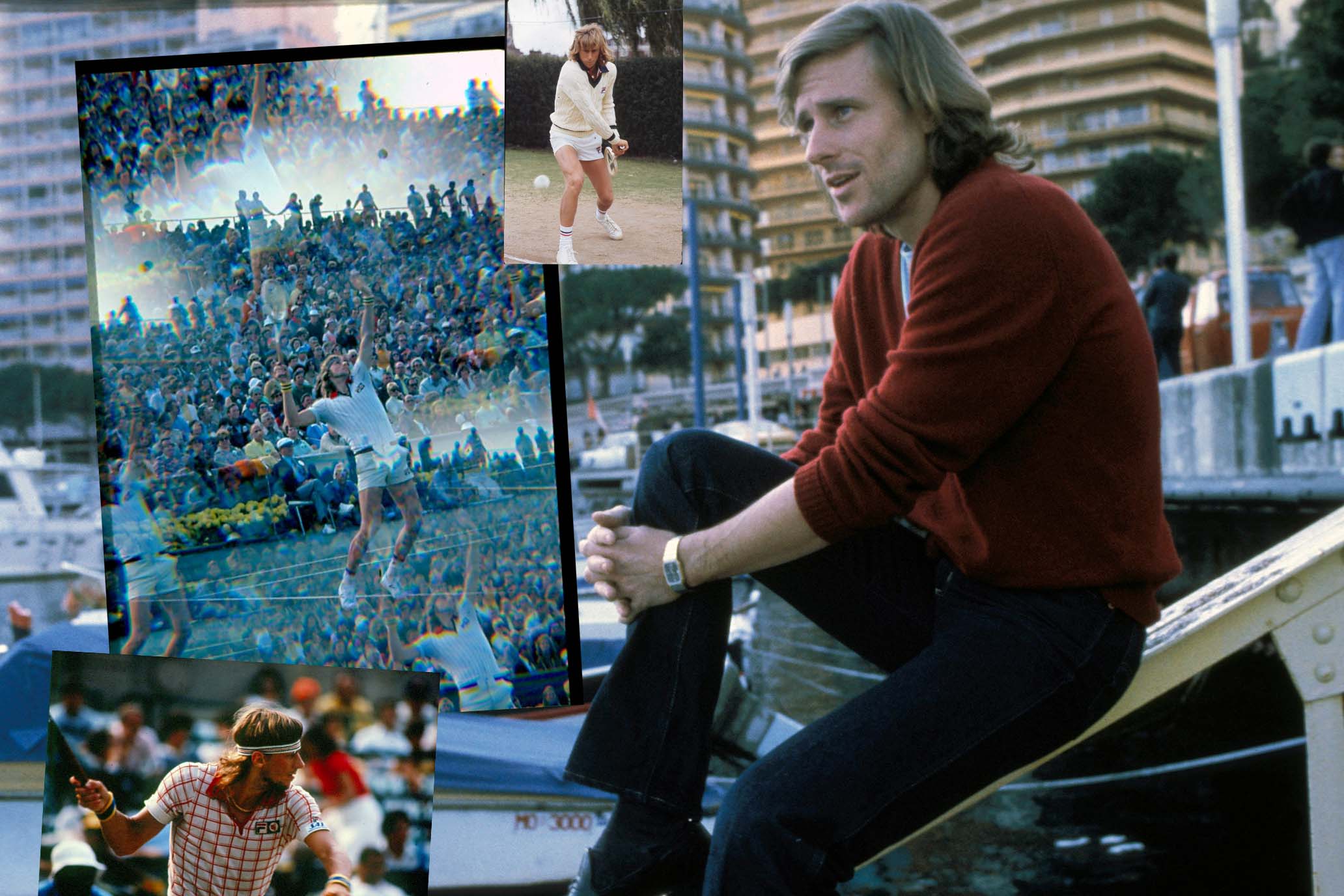

Book Review: Heartbeats: A Memoir, by Bjorn Borg.

Book Review: Heartbeats: A Memoir, by Bjorn Borg.

By Joel Drucker

September 19, 2025

In the literature department I’ve occupied in my mind since the summer I started playing tennis more than 50 years ago, there is a course titled Tennis Belles Lettres that explores the autobiographies of tennis legends. Billie Jean King crafted a tale of destiny. Jimmy Connors took on the world. Andre Agassi dissected his love-hate relationship with tennis. John McEnroe dissected his love-hate relationship with himself.

What should we expect from Heartbeats, Bjorn Borg’s new autobiography (as told to his wife, Patricia Borg)? While the four tennis legends listed above have issued ample public comments for decades, Borg has been exceptionally silent. “For me,” he writes, “standing in front of cameras and talking at press conferences was torture.” As anticipated, a request to interview him for this story was declined.

Nicknamed the Ice Man for his unflappable behavior in the heat of battle, Borg’s exceptional reticence—particularly when juxtaposed against the heat generated by his primary rivals, McEnroe and Connors—only added to the aura he’d long built as tennis’ quintessential cool pop icon. In 1973, the month he turned 17, Borg burst onto the scene with a quarterfinal run at Wimbledon, triggering what was dubbed Borgmania. The Swede with the long blond hair and swimmer-like body emerged as a one-man version of the Beatles, in London that debut year and for the duration of his days at the All England Club escorted by a cordon of British policemen shielding him from teenyboppers and paparazzi, evoking memories of A Hard Day’s Night. First alongside Connors, later with McEnroe, accompanied by poet-musician Guillermo Vilas and disco-era darling Vitas Gerulaitis, Borg by the end of the ’70s had emerged as the lead attraction in tennis’ transition into the rock ’n’ roll era. Prior greats were crooners. These men were electric.

Given Borg’s on-court achievements and crossover popularity, it would have been easy for him to craft a book filled with mild commentary about notable matches and a smattering of the celebrity-laced tales that invariably accompany the journey of a highly accomplished athlete who, once retired from competition, spends the balance of his or her life as the custodian of an image. Should you only seek those, rest assured: Places like the ’70s hot spot Studio 54 and the All England Club each receive appropriate measures of coverage.

“I sat there wondering what had gone wrong,” Borg writes about his state of mind after the 1980 Wimbledon final versus McEnroe had gone into a fifth set despite the Swede holding seven championship points. “John, meanwhile, was fired up, like the young rebel he was.” But as McEnroe would say, let’s face it: A few clicks on YouTube to see the actual match—most notably, its 34-point fourth-set tiebreaker—more eloquently display what proved to be Borg’s fifth straight Wimbledon title run. As I’ve learned firsthand from covering tennis for more than 40 years, the participants speak best with their racquets.

But to his credit, Borg digs into other areas, calling himself out repeatedly for character flaws and regrettable occurrences. “I was so used to being the centre of attention and having someone look after me, ever since I was a kid,” he writes. “If no one was watching, I could go completely off the rails.”

Addressing his long-rumored penchant for substance abuse, Borg writes, “To this day, I’m ashamed just thinking about it. That was the worst shame of all, that my drug problem had reached such a level, with such serious consequences, and all in front of my own father. I didn’t even ask the doctors or nurses how close I’d come to dying. I didn’t want to know.”

Along with this come accounts of failed romances, death threats, and, most recently, an aggressive form of prostate cancer. As Borg describes yet another unenjoyable off-court moment, “The doctors said I would have died if I hadn’t had the surgery. Maybe I had fooled myself into thinking I had a choice.”

Most endearing is the high regard Borg shares for two men, both of whom died in 2008. One is his father, Rune: “Dad was the rock of the family.” The other is his longstanding coach Lennert “Labbe” Bergelin: “Labbe’s huge heart was dedicated to tennis, and he was fantastic with us juniors.” Borg eventually hired Bergelin to become tennis’ first full-time traveling coach.

Here we tap into Borg’s legacy. So subdued is Borg that it’s easy to forget that he was a tennis revolutionary. In addition to the new step of having a handler in Bergelin, Borg was the first player who made significant topspin the essential part of his arsenal. While others such as Lew Hoad, Rod Laver, and Manuel Santana were able to hit many a topspin drive, they’d done so mostly as a supplement to flatter strokes and extensive all-court play. But Borg was primarily a baseliner, his whipped and dipped ground strokes literally altering the trajectory of where the ball went, how points were built, and the whole matter of contact point management. From what Borg commenced, follow the high-bouncing line to such greats as Vilas, Ivan Lendl, Andre Agassi, Rafael Nadal, Novak Djokovic, and Jannik Sinner. Borg literally changed the shape of tennis.

But did Borg’s making prove his undoing? From the obsessive training rituals he and Bergelin adhered to like monks to a shrine, to the narrowness of his attrition-based playing style, to the carousel-like itinerary of tournaments and lucrative exhibitions that blossomed during tennis’ new Technicolor era, it appears that all the ingredients were in place for Borg to grow anxious and world-weary. Describing life in 1980, in the midst of a three-year run when he would dazzle the world with victories at Roland-Garros and Wimbledon, Borg writes that, “despite how well everything was going, I started to feel a creeping sense of panic…. The only time I got any real quiet was in my hotel room, and even that had started to feel more and more like a prison.”

A fatigued Borg took off the 1982 tennis year. The public premise was that he would compete again in ’83. The metaphoric movie trailers for Borg’s return were a series of exhibitions he played throughout ’82. I covered several of those, and the anticipation of Borg back in the mix ran high. But Borg has now issued a confession. Appearing on Johnny Carson’s late-night TV show in July ’82 two days before playing Connors, he writes that, “I talked about having many more years of tennis ahead of me. Of course, none of that was true.”

So it came to be that in January 1983, Borg announced his retirement. Over the next couple of years, he’d play a few more matches, mostly out of obligation. There’d also be a brief return to the tour in the early ’90s, Borg by then unable to compete with his prior effectiveness. Later came fun and games on the emeritus circuit more formally known as tennis’ senior tour.

The result is that a spirit of sadness pervades this book. If life has done well by Borg, tennis has been a mixed bag. He in large part was the sport’s first burnout case, setting the foundation for the likes of McEnroe and Agassi to eventually write books that thoughtfully explored the sport’s toxic qualities. This stream of literature was different from prior tennis books. Tales such as Arthur Ashe’s 1975 work Portrait in Motion and Gordon Forbes’ 1978 work A Handful of Summers depicted the traveling circus as a group of merry marauders, happy to be adults playing a game.

As for Borg, by the end of 1981, a darn good year considering he’d beaten Lendl in a five-set Roland-Garros final and only lost the Wimbledon and U.S. Open finals to an inspired McEnroe, at all of 25 years old, the carefree Beatle had given way to the jaded, late-stage Elvis: caught in a trap. “I was let out to play my matches,” writes Borg, “expected to perform, then locked back in again.” But the prison also made him rich. In that fantasized literature class, what would the professor teaching this book make of the gain-pain ratio between Borg’s youthful dreams, accumulation of wealth, and adult nightmares he appears to have at last recovered from?

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Sabalenka and Swiatek: The Great Rivalry That Isn’t

Sabalenka and Swiatek: The Great Rivalry That Isn’t

Sabalenka and Swiatek: The Great Rivalry That Isn’t

The two best players on the WTA Tour should be a matchup for the ages. So far it hasn’t been.

The two best players on the WTA Tour should be a matchup for the ages. So far it hasn’t been.

By Owen Lewis

September 17, 2025

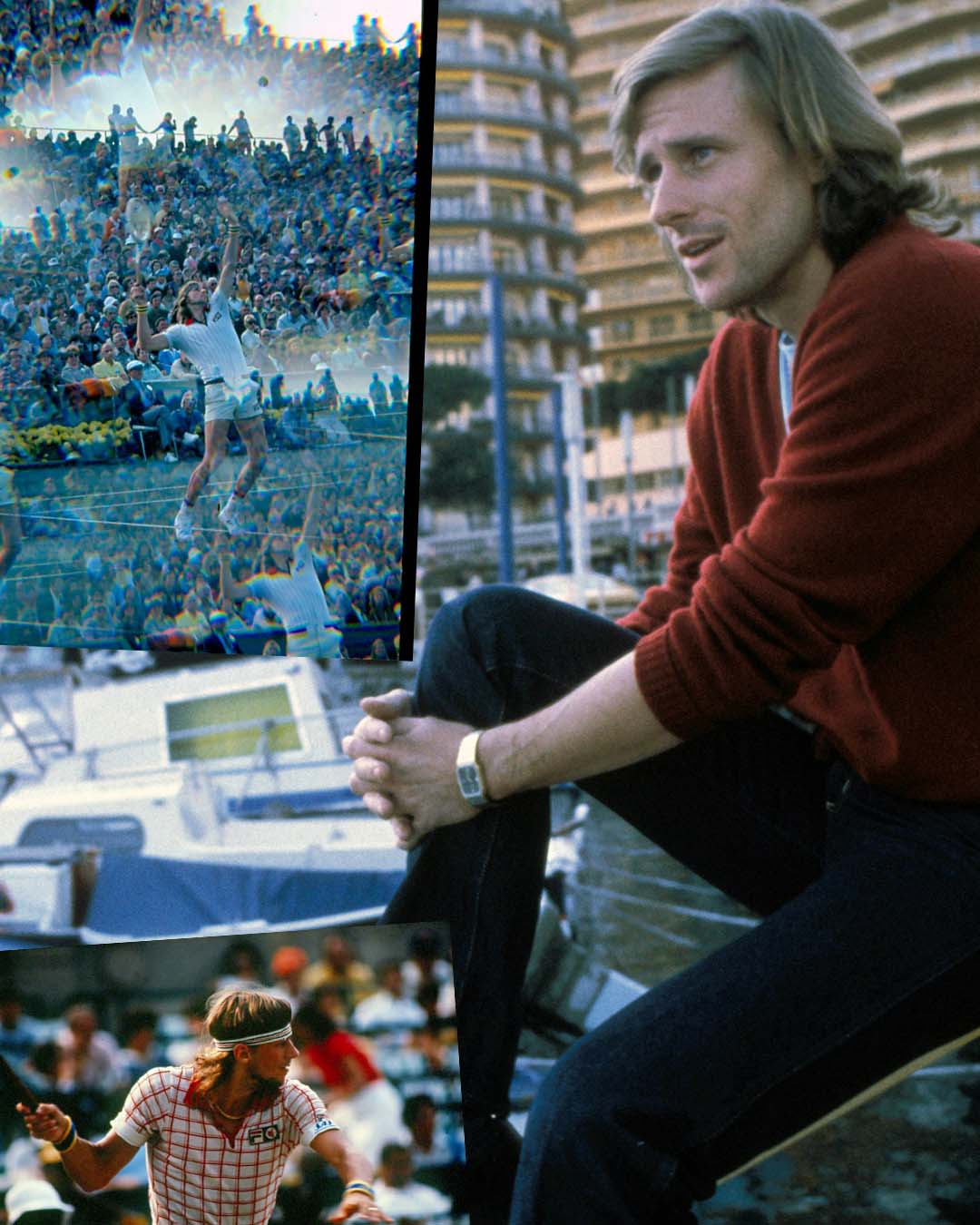

Aryna Sabalenka and Iga Swiatek after their epic clash in Madrid, 2024. // Getty

Aryna Sabalenka and Iga Swiatek after their epic clash in Madrid, 2024. // Getty

I can think of no other explanation: There is a curse on the Iga Swiatek–Aryna Sabalenka rivalry. They have shared seven of the last 12 major titles on the WTA Tour. They have hoarded the No. 1 ranking since early 2022, ceding it only to each other since Swiatek first scaled the mountain in April that year. They have played cinematic, all-consuming three-setters in the late rounds of majors and the finals of the Madrid Open. Their rivalry will decide the better player between them, but likely also the best player of the generation. Swiatek leads every meaningful statistical category: She has more majors, has more weeks at No. 1, leads the head-to-head, and is three years younger. But over the past three years, Sabalenka has gone deep at every single major and might even have matched or exceeded Swiatek’s major-title count had she been able to consolidate more leads in semifinals and finals. During this stretch, my eyes have told me Sabalenka is the better player.

I’m really guessing when I say that, though, because Sabalenka and Swiatek have played just once this year, and only two of their 13 matches were at majors. Neither of those was in a final.

Roland-Garros in 2023 should have been the moment. Swiatek, untouchable clay empress, breezed to the final. Sabalenka, who had just won the Australian Open, had Karolina Muchova pinned at 5–2 and match point in the third set of their semifinal. She didn’t convert the match point, got broken, then failed to win a point against Muchova’s serve when she had the opportunity to break for the match. With Sabalenka serving at 5–5, 40–15 and a tiebreak in sight, the ship seemed cautiously upright once again. Not so: Sabalenka double-faulted away both game points and lost the third set 7–5. Sabalenka has authored several spectacular collapses in similar moments, but this remains her signature meltdown.

Okay, we thought. A freak choke, but they’d make the major final happen before long. An unexpectedly dramatic Swiatek–Muchova final made us forget all about the loss. But the ensuing hard-court majors failed to produce the matchup, too. This time it was Swiatek suffering upset losses that again kiboshed the matchup. Back in Paris in 2024, Sabalenka picked up a stomach bug and slid out in the quarterfinals—the only time in two years she’d departed a major before the last four. Jasmine Paolini was waiting in the semis, whom Sabalenka likely would have crushed to meet Swiatek in the final.

The 2025 Australian Open prolonged the tease to the point of agony. Sabalenka had looked well below her best for most of the tournament but played an authoritative semifinal to make her third straight title match in Melbourne. Swiatek, razor-sharp for the first five rounds, chiseled out a match point on serve in the third set of her semifinal against Madison Keys. Once again, we were one point away from Sabalenka–Swiatek in a major final, and this time it seemed a lock: Swiatek had never lost from match point up before in her professional career. Naturally, she did here, because of the curse. (Also Keys’ boulder-heavy ground strokes.) Swiatek led the fateful 10-point tiebreak all the way up until 8–7, only to lose the final three points. I saw that Sabalenka–Swiatek final die in person, courtesy of a ticketed fan departing early. I stared raptly at Rod Laver Arena’s luminous blue rectangle for the last half hour of Swiatek–Keys, unable to conceive of Swiatek losing until Keys held a match point herself.

Tennis fans often mention that Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal never played at the U.S. Open—they won nine titles in Flushing between the two of them, but somehow never played. Four times Federer held a match point over Novak Djokovic to get to Nadal, four times he lost the point. In 2013 the dream matchup was foiled by a man named Tommy Robredo, who hadn’t beaten Federer in ten tries. These fans, frankly, would not have dared call the opposing magnetic forces embroiling Federer and Nadal a “curse” had they known what was to come with Swiatek and Sabalenka. Both players missing match points that would have locked in the dream final? A literal plague taking the edge off Sabalenka at Roland-Garros in 2024? It was too unlikely to be anything other than dark sorcery.

I’d respect the tennis gods for their sheer stubbornness if they weren’t depriving me of indelible memories from Sabalenka–Swiatek matches. When these two play, the intensity is weighty and constant, even in blowouts. Last year, Sabalenka crushed Swiatek in Cincinnati in her easiest win of the whole rivalry—but Swiatek still saved an astonishing nine match points, forcing Sabalenka to hit a wickedly angled backhand return winner to convert the 10th. And who could forget their 2024 Madrid final, the best match of the year? One point from victory, Sabalenka hit a deep return that figured to set her up to attack on the next shot, only to watch Swiatek pound it for a winner herself. Sabalenka has no shortage of nightmare-fueling losses in huge matches; this is one of a very few she can look back on and honestly tell herself she did nothing wrong.

The lone edition of the rivalry this year, in the Roland-Garros semifinals, was played at an impossible standard of precision and proaction. It felt like watching surgery, and only partly because I had a writing assignment that depended on Swiatek losing at the clay major for the first time in three years. This was the highest-level WTA match of the year, a subpar Iga notwithstanding. Sabalenka played with raw, determined aggression to punch through Swiatek’s defenses. She didn’t even hit the hardest forehands of the day, so desperate and willing was Swiatek to take the initiative first. Each shot that failed to squarely hit its target was promptly punished. The match was a searing reminder of the magic Sabalenka and Swiatek can generate together. They have not played since.

This is not entirely the fault of the top two. The depth of talent and quality on the WTA makes the tour consistently thrilling to watch but is not especially conducive to recurring matchups. (Not like the shallow ATP, where Alcaraz–Sinner finals are likelier to be derailed by assorted physical ailments than another tennis player.) Amanda Anisimova and her wrecking-ball backhand spoiled the party at both Wimbledon and the U.S. Open. There is no shame in losing to her, or to the other players who have spoiled the dream matchup this season.

But watching Sabalenka and Swiatek play beautifully around each other without engaging directly does leave me wanting, and not just for their on-court harmonies but for a concrete answer of which player is better. This battle likely won’t have a clear winner for several years but has me transfixed. If only it weren’t being fought at long range.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Alcaraz and Sabalenka Summon the Tornado

Alcaraz and Sabalenka Summon the Tornado

Alcaraz and Sabalenka Summon the Tornado

Painful losses at Slams were the catalyst for the US Open champions.

Painful losses at Slams were the catalyst for the US Open champions.

By Carole Bouchard

September 12, 2025

Aryna Sabalenka and Carlos Alcaraz are going to need bigger trophy cases. // Getty

Aryna Sabalenka and Carlos Alcaraz are going to need bigger trophy cases. // Getty

Sometimes the best thing that can happen to a winner is losing. Carlos Alcaraz and Aryna Sabalenka showed us this by clinching titles in New York, having both bounced back from crushing losses at Wimbledon in June (not unlike Jannik Sinner, who prevailed in London after losing an epic five-setter in Paris to Alcaraz, despite three match points in the fourth set). When you’re already the best, you need a much stronger trigger to reach the next stage. And what better motivation than losing in the last stretch of a Grand Slam when your sole tennis ambition is to win them all?

To Sabalenka’s credit, she’s undoubtedly the player who has evolved the most and in the most radical ways to become the champion she is now. She had to control her temper, control her power, clean up her technique (that serve has come so far!), and find a way to bring variety to a game that seemed immune to it. Despite all that progress, she had yet to win a Slam in 2025 and seemed to need a double dose of defeat to get over the last hurdle. The World No.1 didn’t get there after losing to Coco Gauff in a messy Roland-Garros final. No, she needed a loss in the Wimbledon semis to an ascendant Amanda Anisimova for her to buckle down.

Carlos Alcaraz was already in control of most of what he needed, but his problem was Jannik Sinner, who continues to level up. The Spaniard, who won his sixth Grand Slam title in New York and returned to the rankings throne for the first time in two years, was on the verge of losing ground to the Italian, and he knew it. More to the point, his coach, Juan Carlos Ferrero, knew it. The margin on clay was thinner than thin, and the Wimbledon title was gone, but that loss birthed Carlitos Version 2.0 in New York, just as those tough losses triggered Aryna’s change of mindset. No champion can afford to remain in denial or delusion. And so, both asked the mirror on the wall and didn’t like the answer that came back.

Going into Wimbledon this year, Sabalenka said that “it felt like, if I made it to the final, it means that I’m going to win it. And I didn’t expect players to come out there and to fight. I thought that everything was going to go my way easily, which was completely the wrong mindset.” It is extraordinary that Sabalenka, who has gone through heartbreaks in Grand Slams before putting the puzzle together, and who faces an era where Iga Swiatek has been as dominant—if not more—than her, felt she would be an invincible force the moment she set foot in the final of a major.

Champions of that caliber need a healthy dose of confidence and delusion in equal measure, but the key word here is “healthy.” Being denied again at Wimbledon was the perfect shock to the system for Sabalenka. And the US Open ended up being the perfect exorcist for all her ghosts, as she won that fourth Grand Slam title against Anisimova, her SW19 nemesis, by remembering she wasn’t owed a Grand Slam title but had to fight tooth and nail for it.

“I really wanted to give myself another final, to prove to myself that I have learned those tough lessons and that I can do better in the final,” she said ahead of the US Open final. “I have learned the lesson, and I will never behave like that again. I let my emotions take over, and I am not like that anymore. It will never happen again. I have to trust myself and give it my all. At Wimbledon, I doubted myself a lot, and that is the main reason for my unforced errors.” And so at Wimbledon, she finally made that promise to herself that it wouldn’t happen again. And, at least in New York, it didn’t.

Alcaraz, who suffered for five and a half hours in Paris to keep his crown, already knew all of this, of course, when he landed in New York. But what he didn’t know anymore after Wimbledon was how to keep Sinner at bay. And so Ferrero found him the answer: a two-week “let’s take him down” retreat. Here Wimbledon didn’t trigger an overhaul but an epiphany. By starting to plan for Sinner more originally, Ferrero pushed Alcaraz to get back to himself. And so, to return to a genius kind of chaos. All the angles, all the effects, all the variations. Everything everywhere all at once. Summoning a tennis tornado like only he can.

“The consistency of my level during the whole tournament has been really high, which I’m really proud of, because it’s something I’ve been working on. Here I saw that I can play really consistent,” Alcaraz said after the final. Wimbledon had shown him that to stay ahead of Sinner, he had to reach the Italian’s level of steadiness. Now, finding steadiness in that tennis storm he’s been delivering is quite the feat!

Sinner had already used his trigger power from Paris to win Wimbledon, so a newly improved and steady Alcaraz must have come as quite a shock. The challenge now for both winners is to continue to train with a sense of urgency, despite being at the top of the rankings. Now the question is: What’s next? Can they keep their noses out in front of opponents that are just as likely to come back stronger?

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Let the Winners Fly

Let the Winners Fly

Let the Winners Fly

Amanda Anisimova and Aryna Sabalenka prepare for a slugfest.

Amanda Anisimova and Aryna Sabalenka prepare for a slugfest.

By Giri Nathan

September 5, 2025

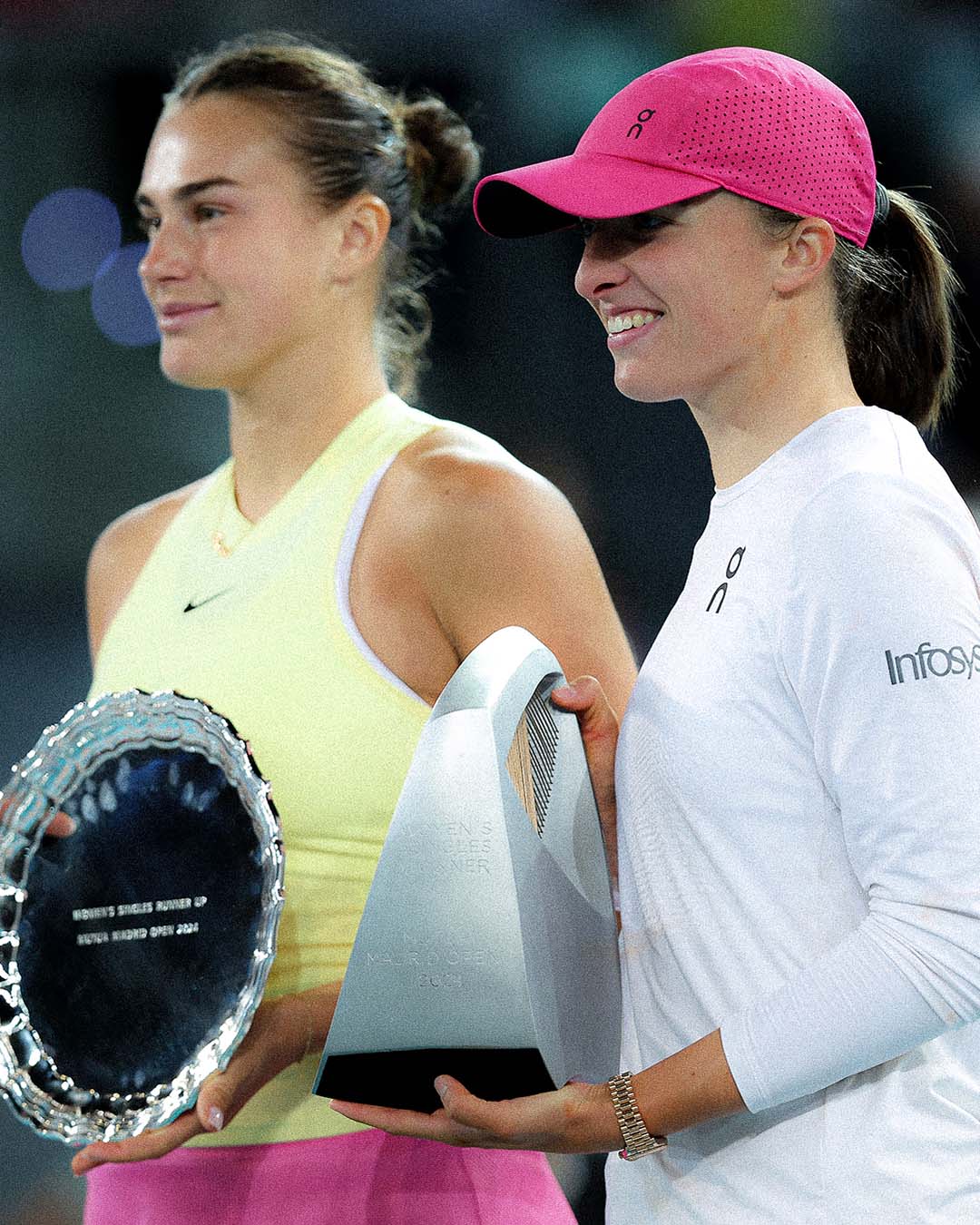

Amanda Anisimova and Aryna Sabalenka before their semi-final matches. // Getty

Amanda Anisimova and Aryna Sabalenka before their semi-final matches. // Getty

Quite often this semifinal Thursday is the best day of tennis that the US Open has to offer. And this one might have been the best of all Thursdays in recent memory. Two three-setters, both high-quality, and both a little nervy in the best ways.

After Aryna Sabalenka went down a set against Jessica Pegula, I began to wonder if she was on course to have the greatest Slamless season of all time. Top player in the world, deep runs at all four majors, and…none of the biggest titles to show for it? But she soon corrected her course. In truth this matchup always looks pretty comfortable for her. During a mid-match interview, Pegula’s coach, Mark Knowles, made a comment to the effect that Sabalenka appears to enjoy hitting the clean ball that comes off Pegula’s racquet.

I have always had that same impression, and it’s admittedly not so subtle a thing to pick up on, given the 7–2 head-to-head in Sabalenka’s favor heading into this match. She has the obvious advantage in offensive weaponry, and those flat, low, consistent shots from Pegula that perturb so many other opponents only seem to aid Sabalenka’s rhythm. Pegula barely put a foot wrong in the deciding set, in which she lost only four points on her serve, and somehow still lost the match—as she herself wryly observed, alongside a selfie with a post-loss Honey Deuce. There’s not all that much Pegula could have done differently in this matchup, and it must be frustrating, but to her credit, she made the defending champ work hard until the last ball, even as Sabalenka sweated through some flubbed match points.

Better still was the second match, a long shoot-out between Naomi Osaka and Amanda Anisimova. On paper this was a match for people who like to see the tennis ball get thoroughly mashed, and the reality was everything we’d been hoping for, plus some. Both players have the power to end points at a whim, and both seemed to grasp the nature of the matchup: Whoever first surrendered a sizable patch of open court was going to lose the point. This was not to be a match won in slow, grinding rallies. Second serves were feasted upon at all times. Sometimes so aggressively that, for long stretches of play, it looked as though the server was somehow at a disadvantage. One Osaka return came in so fast it toppled Anisimova onto her back; Anisimova, for her part, won a startling 66 percent of points when facing second serves.

The scoreboard was tight from start to finish—they split the first two sets in tiebreaks—and the pressure was inescapable. At one point, Anisimova bonked herself on the head quite hard with the racquet, and at others, Osaka chucked hers around the court. Anisimova loosened up in the match’s waning moments, though, reeling off those eerily pure backhands that are her singular stamp on the game, and she managed to serve out the match. This semifinal was the clearest sign that both players, who had stepped away from tennis for personal reasons, have completed their journeys back to the very top of the sport. Now the WTA has been blessed with some high-profile rivalries that we couldn’t have anticipated this time last year, or that we did not expect to ever be so relevant again. Saturday’s final is one of those: Anisimova versus Sabalenka, a rematch of their Wimbledon semifinal, and the epitome of first-strike tennis. Let a thousand winners fly.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

No Fairy Tale

No Fairy Tale

No Fairy Tale

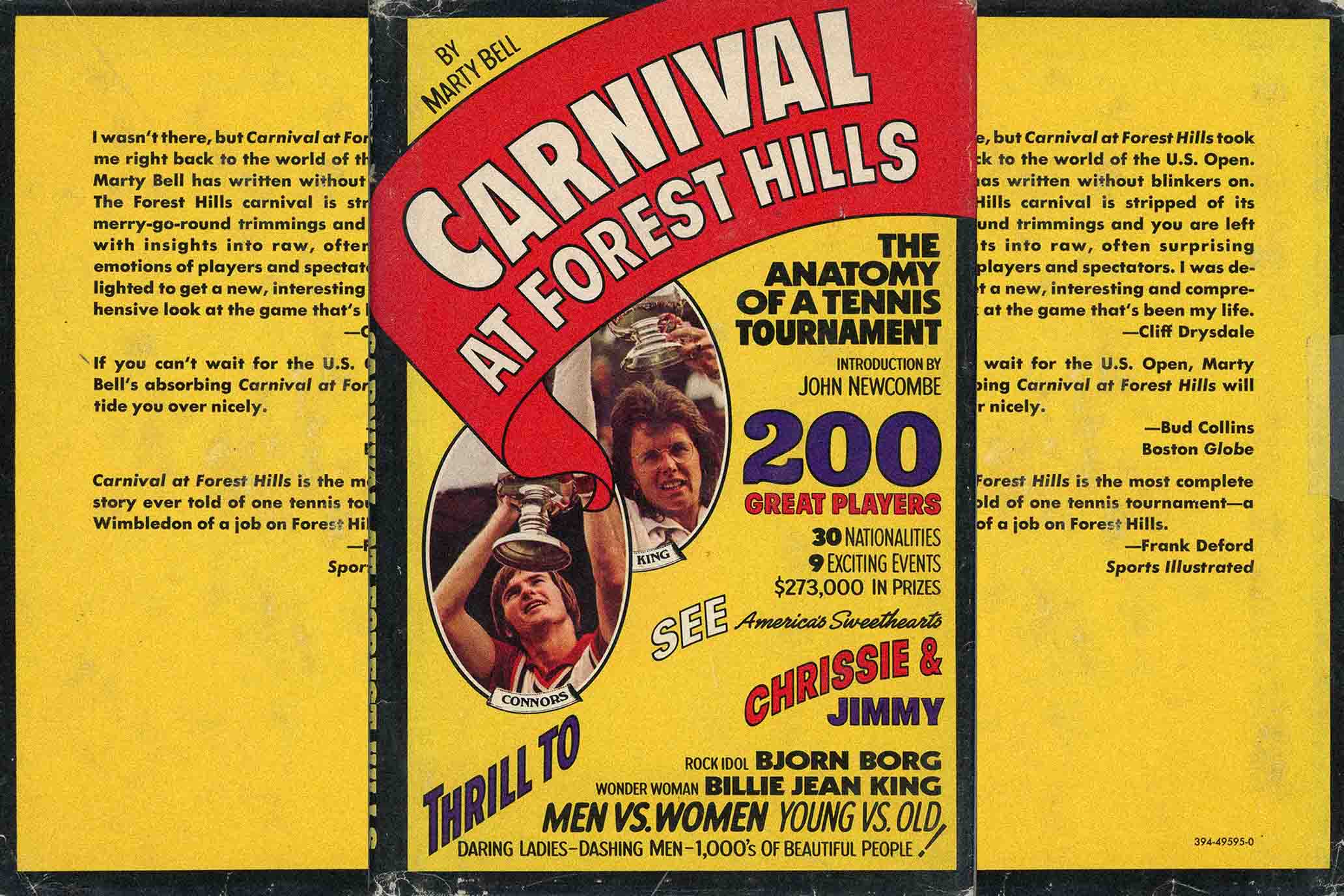

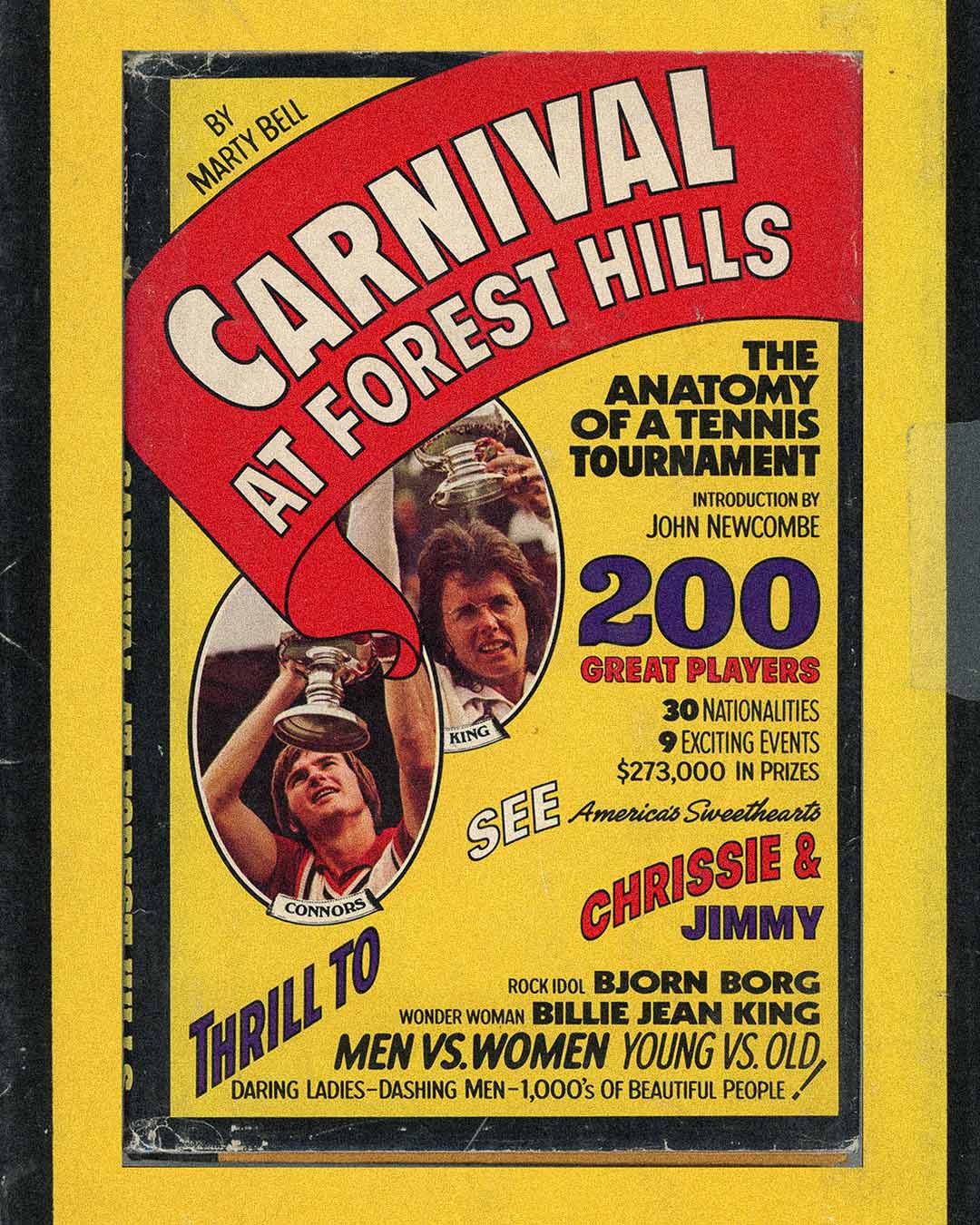

Reappraisal: Carnival at Forest Hills by Marty Bell.

Reappraisal: Carnival at Forest Hills by Marty Bell.

By Joel Drucker

September 4, 2025

Chris Evert and Jimmy Connors, who were very briefly “America’s Sweethearts”. // Getty

Chris Evert and Jimmy Connors, who were very briefly “America’s Sweethearts”. // Getty

My weekend prior to this year’s US Open was spent at the induction ceremony of the International Tennis Hall of Fame. Located in Newport, R.I., this subdued and cozy venue had housed the U.S. National Championships until 1914. The Sunday morning following the ceremony, I headed west and south across New England and into New York to cover the US Open at the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center—a locale arguably not subdued and cozy enough.

Alongside those trips came a journey to a time and place theoretically in the middle. It happened in the form of rereading a book titled Carnival at Forest Hills. This is the tale of the 1974 US Open, played then at the West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills, a genteel neighborhood in Queens. Does that make this venue just right? Given what was going on in tennis then, think twice before you bathe yourself in nostalgia.

Consider the decade from 1968 to ’78 tennis’ Transitional Era. Nineteen sixty-eight marked the commencement of Open tennis, amateurs and pros at last unified, the sport now entering the contemporary sports world of commercialism. In the United States during that time, participation in the game tripled. By ’78, tennis’ growth was in large part symbolized by the US Open relocating to the current public facility at Flushing Meadows.

Carnival at Forest Hills captures the Transitional Era smack in its tumultuous middle. “Old-time members must have been as dismayed as the old-line Washingtonians in 1829,” writes author Mary Bell, “when Andrew Jackson opened the White House to the public and invited his frontier friends to a wild inauguration party. Tennis had become democratized.”

To further extend that 19th-century, P.T. Barnum-like quality, savor the book’s poster-like cover. The title is splashed in white letters against a red background and a bright yellow full page. The top seeds, Jimmy Connors and Chrissie Evert, engaged to be married at the time, are referred to as “America’s Sweethearts.” Bjorn Borg: “Rock Idol.” Billie Jean King: “Wonder Woman.” All joined by “1,000’s of Beautiful People.”

Remnants of tennis’ feudalistic past remained, ranging from the erratic bounces of the grass courts, to players expressing anger at how they were treated by haughty amateur officials, to the words of a volunteer linesman who lamented the increasing presence of money. There was also tremendous intimacy and access, with players, officials, fans, and media spilling over one another as they packed themselves into the West Side Tennis Club. The presence of such sporting Australians as the swashbuckling defending champion John Newcombe, his best friend/doubles partner Tony Roche, and the relentless genius that was 39-year-old Ken Rosewall (a stylistic ancestor to Roger Federer) served as reminders of tennis’ tradition of sportsmanship, elegance, and cucumber-like cool in the heat of battle. “Rosewall, as always impeccably groomed and dressed in his lucky yellow shirt and wristbands,” writes Bell, “seemed to spend the first set studying his opponent’s game.”

Then there was the new. The 1974 US Open marked only the third year that players were permitted to wear non-white clothing, hence a lively, quintessentially ’70s Technicolor showcase of pink, red, blue, yellow, and more. It was also the fifth year of the tiebreaker, in those days a rapid-fire version played to five points (no two-point lead). The next year, the tiebreaker would make an incremental shift to the seven-point version now employed. But one ’74 US Open protocol is long gone: winner and loser occupying the same room during a post-match press conference. Following a round-of-16 loss to Connors, ’73 finalist Jan Kodes declared in front of Connors’ face that “In my opinion, only two players are left in the tournament who I think can win: John Newcombe and Stan Smith…. I think Jimmy has third place.”

But while tennis experimented with such transitory elements as new garb, scoring systems, and player-press interactions, Bell observed something far deeper that was altering the complexion of the sport. While once the circuit consisted of a fraternal flock of solo acts circling the globe together, such top players as Connors and Evert had begun to change that dynamic. “[Connors] and Chrissie came to this and every tournament completely surrounded by a group of people whose only purpose was to guide them to the championship,” writes Bell. “The shell isolated them from everyone and everything else.” So began what’s become even more prevalent these days.

That was just one observation that delivers more depth than the book’s breezy title would lead you to believe. Neither raffish nor jaded, Carnival is concurrently highly readable but also quite thoughtful. Having read dozens of sports books authored in the late ’60s and early ’70s, I’ve long noticed in works of those years a compelling mix of appreciation, engagement, access, and analysis. Thanks largely to the growth of television, sports at that time had become popular enough to warrant broader sociocultural assessments—but not so big to the point where athletes were kept distant from the press and public. A writer like Bell could easily observe and chat with many tennis players, including even the very best. That’s hardly the case now, when players are mostly available during frequently sterile post-match press conferences and prefer to tell their own stories via social media. Over the years, that increasing distance has made many a journalist jaded, cynical, and occasionally even bitter about how the cocoon makes it difficult to write great stories.

No such rancor is present in Carnival. As Bell follows the tournament, day by day, making concise dives into selected matches of interest, his affection for tennis endures. Writing about a gem of a semi between Evert and Evonne Goolagong, Bell writes that “Now on point after point, they just stood back at the baseline, hitting as hard as they could for as long as they could.” In addition to match analysis, there are snapshot-like portraits of such notables as Arthur Ashe and his quest for more Grand Slam glory, Stan Smith’s mid-career crossroads, Goolagong’s alluring playing style, Newcombe’s charismatic personality, Borg’s popularity, and many others.

As you’d expect when reading about a competitive endeavor, those who win most emerge as the lead players. In the case of the 1974 US Open, those spots were filled by the eventual singles champions, King and Connors. Bell adroitly parses the polarizing qualities of each, albeit for drastically different reasons—King for leadership skills that some perceived as overly bossy, Connors for his highly isolated manner. “What are friends?” Connors asks Bell as they chat on the deck of the club. “I’d rather have a dozen good friends than a hundred who stab you in the back.”

Lest you think Connors has always been a New York darling, that was far from the case in 1974. During Connors’ 68-minute 6–1, 6–0, 6–1 victory over Rosewall in the final, a fan yelled out, “Connors, you’re a bum.” But as Bell writes, “The jeers from the stands only seemed to encourage him to be meaner and more aggressive. And he could always look to the marquee where the inner circle huddled together.” Bell went so far as to compare Connors to Richard Nixon, the American president who’d resigned a month prior. As Bell saw it, Nixon and Connors were both ambitious, tenacious, and uncouth competitors.

In the spirit of the best primary sources, Carnival vividly demonstrates how even then, the tennis world was hardly innocent. Open tennis had triggered both opportunities and challenges. To this day, the sport continues to wrestle with that legacy.

Carnival at Forest Hills by Marty Bell.

Carnival at Forest Hills by Marty Bell.