Hard Reset

Iga Swiatek's Hard Reset

Iga Swiatek's Hard Reset

She needed one. Her team obliged.

She needed one. Her team obliged.

By Carole Bouchard

July 18, 2025

Iga Świątek buckles down during the Wimbledon final. // Getty

Iga Świątek buckles down during the Wimbledon final. // Getty

You don’t go from losing one of your best shots (the forehand) on a surface you have dominated on (clay) to finding it again mere weeks later on the surface that supposedly bedevils you the most (grass) without some kind of major intervention.

Sure, as Iga Swiatek’s coach, Wim Fissette, explained during Wimbledon, her team tweaked her serve and forehand and made adjustments to her footwork this spring, and that work was a key factor in Iga’s triumph on Centre Court on Saturday. However, we know that to be a champion the results won’t come without the proper mindset, no matter how much you tweak their actual games.

I spoke with Swiatek’s team after the Wimbledon final to understand just how they had rebooted her system. A few days before the final, Fissette had told me that the former world No.1 “wasn’t herself” this year until Paris. “In Madrid and Rome, she was probably at her worst from the past years,” he said. Daria Abramowicz, her performance psychologist, confirmed that the team sat Swiatek down and told her—and each other—some hard truths. It looks to me like Swiatek’s hard truths were about how her attitude needed to change.

“The big moment actually was between Rome and Paris,” Abramowicz said. “We had a few difficult conversations within the team, and the one thing that I can tell you about Iga is that she can listen to the tough stuff, and she embraces it. That also says a lot about her as an athlete and a human being. In Paris, we could see adjustments in the attitude, work, and mindset, on court, off the court, and I immediately thought that we were going in the right direction.”

Since then, Swiatek’s error count and her impatience and frustration on court have decreased. “It’s more a mindset of, ‘Winning is one thing, but now how am I becoming a better tennis player?’” Fissette said. “It’s better to be focused on that than be like, ‘I need to win every tournament.’ You need to become a better tennis player, and then the rest will follow.”

The reset worked so well that Swiatek returned to work with a huge hunger to improve, despite the loss in Paris. “After Roland-Garros, she jumped into the work, which was good to see and hear,” said Abramowicz. “She put in a lot of work in terms of attitude and reframing some beliefs. There was no turning point, but the process gradually changed since Rome. There can be a certain amount of grit that sometimes also changes into stubbornness, with obviously more than a bit of perfectionism. The question is how to approach these situations and how to reframe. I just tried to show her how good of an athlete she can be, because that’s still the territory that we can discover.”

Iga finally accepted the changes her coach wanted to make. Nothing better than losing to be convinced, which is logical: When you’ve been winning that much, why would you believe you need to change? That was the other pivotal moment in the coach-and-player trust situation: the match against Elena Rybakina in Paris. A few steps back on the return and a win; that’s all it took after that discussion with the team for Swiatek to give up on what has also made her the player she is: her stubbornness.

“When you start working with someone, you cannot ask them to trust you,” Fissette said. “It has to come naturally, and with Iga having so much success with the previous coach, it was not easy. I had to work hard and find my moment to make a difference. I believe in my ideas, but I also keep adjusting to what’s the right approach with the player. Finding the right moment to make a change, which is not easy, but the Rybakina match in Paris was a huge turning point where she realized what I was saying was working.”

The team also challenged Iga’s limiting beliefs. She admitted she never believed she could win Wimbledon, for example. She also told Fissette, from the beginning, that “fast serve is just not for me.” How can such a champion not believe the sky is the limit—and how it was up to her team to believe when she wouldn’t?

Maciej Ryszczuk, Swiatek’s fitness coach and physiotherapist, was surprised by how she agreed to it all after losing in Paris. “It was a surprise for everyone,” he told me. “Especially on this surface, believing that she can do it, because it was the crucial part. The game was there, but she was struggling with her mental side. We just adjusted the footwork to decelerate a little bit more, with a bit less sliding, to be prepared quicker for the ball. And that’s it. She had it from the beginning, but she needed to believe it.”

People underestimate the strength of Iga Swiatek’s personality and how reluctant she is to change until she has seen proof that it’s needed. “As soon as these top players make the click of first believing and then feeling that the choice is right, then it’s always, ‘Okay, let’s go for it,’ and so it can go fast,” Fissette said. People also underestimate how tough it’s been for her to adjust to a new coach, new ideas, new losses, and so many changes. Fissette told me he had to learn how to talk to her, how to respect her process. I asked Abramowicz what it had meant for her work with Swiatek.

“I’ve never spoken so much to any other coach before,” she told me. “We talk so much about communication, because for Iga, the challenge is having a first non-Polish coach. I try to prepare her through mental training in English, with various tasks in English, so that when she’s under stress and pressure, she can transition into English. However, on the court, you can still see her revert to Polish when under pressure or being overwhelmed by emotions. So we try to develop protocols, patterns, and systems. She also appreciates having a reason for what she’s doing. She likes to understand, speak up, and she asks questions more than ever before, which is something I want to see in terms of environmental mastery and communication within the team. She learned how to manage the team, how to communicate, how to exactly follow whatever she wants, but also to embrace tough things and be able to listen to them.”

Sure, they would have preferred the reset to start hitting hard for Roland-Garros, but seeing how visibly more free Swiatek has been swinging out there throughout Wimbledon, one can wonder if, for the reset to work fully, she needed to clear her entire system beforehand. And Roland-Garros was taking up a lot of space in the hard drive of her tennis beliefs. You could see on her face when she clinched that Wimbledon title that a new world was opening up.

Fissette feels the same. “We have the right answer now, so it’s going to be easier for me. If she focuses on the right things, we know that she has all the answers. She’s still so young and has a lot to learn. My focus is on making her a better player; I want to see more variety in the game.” Has he ever thought he had accepted the wrong job? “No. I never doubted. A career is always going up and down. Iga learned a lot in the last month, and so did I.” Not all reboots are successful, but this one for sure ended up being a blockbuster.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Tennis as Death

Tennis as Death

Tennis as Death

Review: Andrey Rublev: Breaking Back

Review: Andrey Rublev: Breaking Back

By Owen Lewis

Jul 5, 2025

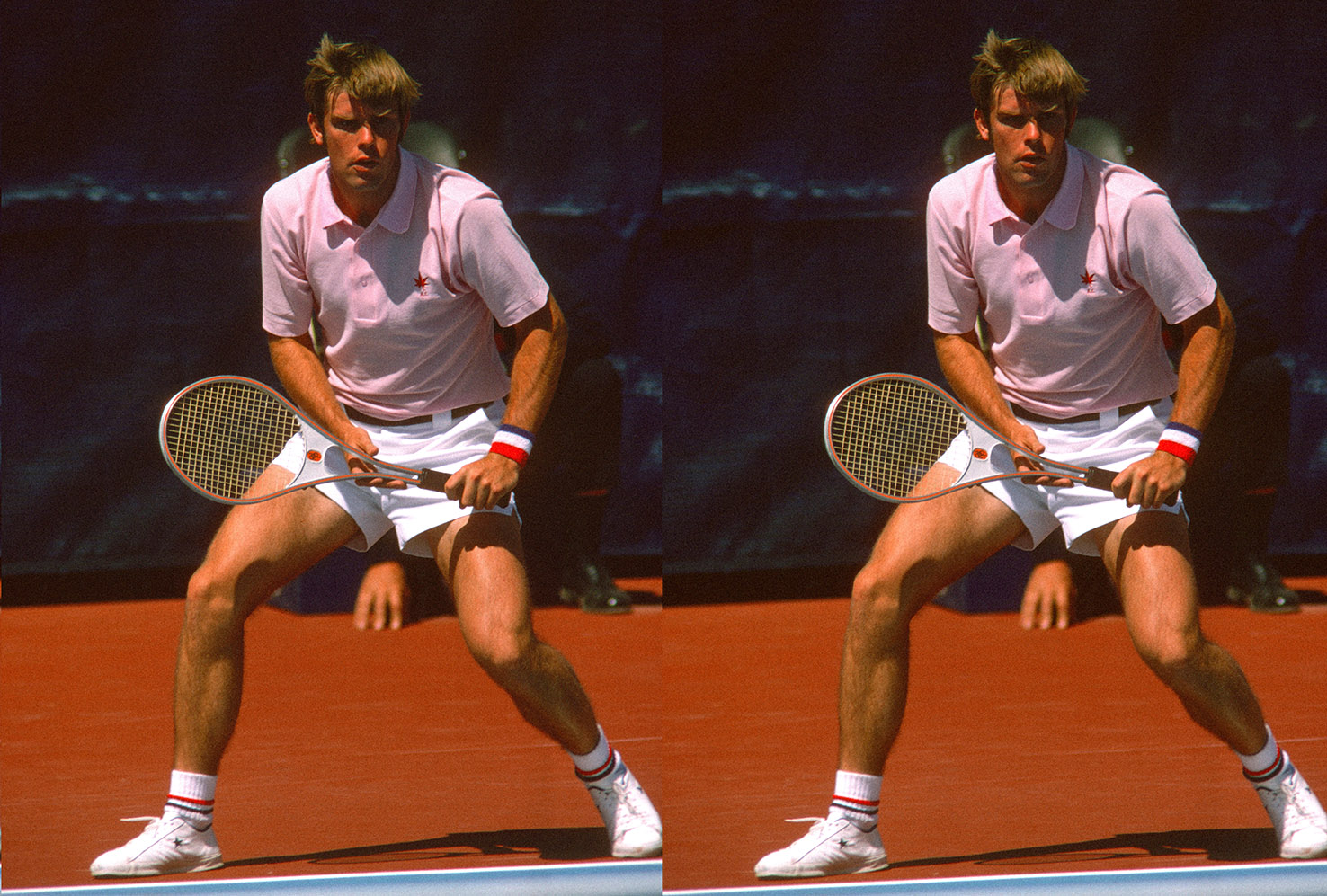

Andrey Rublev during darker times, at the Swiss Indoors Basel. // Getty

Andrey Rublev during darker times, at the Swiss Indoors Basel. // Getty

The first look at Andrey Rublev in his YouTube/ATP Tour documentary Breaking Back comes via his countryman Karen Khachanov. “It was an under-10 tournament in Russia, and I heard from a few courts behind me screams, crying,” Khachanov says. “One boy was laying over, throwing balls, racquets. They told me, ‘His name is Andrey Rublev.’ I say, ‘Very good. Nice to meet you.’ [Laughs]”

That Khachanov seemed unsurprised in his recollection is no coincidence—this sport has a way of desensitizing the shock of watching a player act out their self-hatred. At the 2008 Miami Open, Mikhail Youzhny raged so fiercely at his cowardice for a pitty-pat backhand into the net that he turned his racquet on his own brain, whacking his forehead with the strings until dark blood trickled down his scalp. Even this disturbing masochism earned only a blithe look from his coach, and a startled emoji in Tennis TV’s caption for the video when, in 2021, they released extended highlights of the match. Compare that reaction with the uproar over Aryna Sabalenka’s salty comments after losing the Roland-Garros final to Coco Gauff, and you’ll have a good idea of how much these tantrums move the emotional needle for most observers.

Rublev, though, took self-recrimination to such a visceral degree in his darkest years that many grew uncomfortable while watching him play. His fury was not only destructive but desperate. He’d howl after a miss, eyes practically pulsing out of his head. He drew blood from his knee via repeated racquet whacks. At the 2024 US Open, after a shoddy forehand error, Rublev clapped his left hand onto his racquet strings with such force that he cut it and needed medical attention. The miss came at 3–1 in the first set, so early on that it couldn’t possibly have proved costly all on its own. No tennis mistake is worth losing blood over; even if one could be, this wasn’t close to being it.

In Rublev’s on-court interview following his fifth-set tiebreak escape from a fourth-round match with Holger Rune at the 2023 Australian Open—Rublev had had so many leads he’d never be able to think about anything else if he’d lost—he likened crunch time to being held at gunpoint. He crosses himself when his matches end, suddenly seeming to gain a measure of peace, win or lose. In light of quotes like this, it made sense. After hours of feeling like life hung in the balance, I’d accept salvation or oblivion too.

“When you were watching him, you were saying, ‘Okay, he has a lot of potential,’” Galo Blanco, Rublev’s coach and agent, says in the documentary. “‘But he’s completely crazy.’” Breaking Back efficiently chronicles how Rublev ended up so tortured: He was raised with the mindset that tennis mattered above all else, so when his tennis began to fray, so did his world.

The stifling pressure to win a major title only worsened his anxiety (a word Rublev repeats dozens of times throughout the doc, and pronounces “ank-shitty”). Rublev takes the gun-to-the-head metaphor even further to the ATP’s cameras: “Every time I was going on court and things were not going my way, the feeling is like you’re dying. It’s like someone came to murder you.” When Rublev lost, he felt like that someone had succeeded.

In off-court moments on camera, Rublev is light and genial, poking fun at himself and others, eagerly hugging his friends. Compartmentalization can rip perception from reality, that I knew. I also wondered whether Rublev might have been happier in previous years if he’d quit tennis. The tragic thing, as an observer, is that his violent reactions after his errant shots seemed only to ruin his mental health rather than improve his tennis. He is sublimely skilled, better than you or me or everybody on the planet except a dozen or so people could ever get at tennis. But he is also limited. His big forehand is his best shot; it will never be as big as Jannik Sinner’s. He does everything well and nothing as well as Carlos Alcaraz. When Djokovic rips into himself, you get it; you’ve seen what he can do at his best and understand how anything short of that glorious, stifling peak is a disappointment. Rublev, who has made 10 major quarterfinals and lost them all, demanded a perfection from himself that he was incapable of producing.

In time and after a lot of pain, tennis-related and not, Rublev came to realize that expectations of winning a Slam were “bullshit,” that he’d die for real at the rate he was going. “I still love [tennis],” he says. “I still want to achieve as much as I can, but in a healthy way, not a struggle way.”

The realization is euphoric. To this viewer, the expectation that top players win a major is indeed hot crap. A player’s chances of doing so depend almost wholly on how many years in age separate them and various generational talents, who gatekeep the game’s shiniest prizes with a Cerberusian vigor. If Rublev were to win a major, he’d earn the privilege of brief catharsis and Big Three-pilled fans calling the crowning achievement of his career a “Mickey Mouse title” for the rest of time.

Rublev seems to be suggesting that the goal of a financially sustainable tennis career should be to escape with one’s mind intact. Players frequently find it unfulfilling to reach their lifelong objectives—think of Agassi writing in Open that he felt nothing once he reached the top spot in the rankings, or Dominic Thiem losing all his motivation after he finally won a major. The price for these cold prizes is high. Expectations spiral ever higher, unavoidable losses keep you up at night (Djokovic, tennis king of kings, has lost 13 major finals), you play even more matches. The real achievement, then, is not going crazy while navigating this demented maze, to reserve a bit of yourself from the game. Give everything to tennis, and what you get back will be inevitably less.

As top-ranked players have suffered upset after upset at this year’s Wimbledon, Rublev has progressed through the draw calmly, making the fourth round to live up to his 14th seed. Hiccups that once would have had him screaming his vocal cords raw—a missed match point and a fourth set in his opener against Laslo Djere, back-to-back double faults as he tried to serve out his third round against Adrian Mannarino—he now accepted with grace. Against Mannarino, Rublev hit a sick, sliced forehand pass on the defensive in the final game, a shot you’d have thought came from Carlos Alcaraz had the video stream blurred out the player who hit it. An ace on the next point sealed his win. Never did I worry that he was going to hurt himself.

Rublev sits on the beach at the end of the documentary, giving a voice-over that sounds driven more by philosophy than by the fiercely competitive instincts that power elite players. He is sleeping better and spending more time with himself. “It’s not easy because it’s super painful in the beginning,” he says of fixing himself. “But then it’s relief.” Watching him suffer the beginnings of a choke at moments during his Wimbledon run and react as if only a tennis match is at stake, not his own life, I see what he means.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Andrey the Giant

Andrey the Giant

Andrey the Giant

Andrey Rublev might just be the last original “NexGen” star standing.

Andrey Rublev might just be the last original “NexGen” star standing.

By Giri Nathan

July 4, 2025

Andrey Rublev looks for inspiration during his second round match at Wimbledon against Lloyd Harris. // Getty

Andrey Rublev looks to the heavens during his second round victory over Lloyd Harris at Wimbledon. // Getty

I used to say to friends, offhand, that Andrey Rublev could win a Slam someday. The draw might open up just so, and the tempest in his mind might be subdued for just seven matches in a row, and that would be it. He had the weapons to pull it off. He just needed some luck, and he needed to stop beating himself up (both figuratively and literally).

I no longer say this.

In the years since, it has become clear that the Slams will be won by two even younger guys, with one old guy sticking around to make everyone work a little harder. And it appeared that Andrey Rublev himself had hit a clear ceiling. He was the first of his age cohort to reach a Slam quarterfinal, way back when he was a 19-year-old, and he’d reached nine more quarterfinals since. But not once had he advanced to the semifinal. He has been stopped by the usual names, plus the occasional surprise: Rafa Nadal, Daniil Medvedev, Stefanos Tsitsipas, Marin Cilic, Frances Tiafoe, Novak Djokovic, Jannik Sinner.

This Wimbledon, however, is looking a little sunnier for Rublev. It seems to me that both of those conditions for success—a decent draw and a sound mind—have been met. The draw was opened up by a first-round bloodbath that claimed 13 seeded players. Some of the victims were guys of Rublev’s generation, who now comprise tennis’ upper middle class, idling in their late 20s, having been leapfrogged by Carlos Alcaraz and Jannik Sinner. (Interestingly, Rublev was the only player on tour to beat both Alcaraz and Sinner in 2024.) Gone in round 1 were Rublev’s peers Daniil Medvedev, Sascha Zverev, and Stefanos Tsitsipas, who lamented a high-rolling opponent, a total lack of joy in life, and a bad back, respectively.

When asked about the mass exodus of seeds, Rublev said, “It make me feel I’m not the only one!” He knows the feeling; he spun out of Wimbledon in the first round last year. During that loss, he whacked his own knee with his racquet seven times in a row and drew blood. It was part of a larger pattern of outbursts that season, which grew concerning even by Rublev’s violent standards. “I was completely lost,” he recalled in an interview this week with Tennis Channel, looking back at last year’s mental struggles. “It was nothing to do with tennis…. I was getting help from every place possible, but in the end the one who helped me a lot was Marat Safin.” In one of the ATP’s most spiritually apt pairings of player and coach, this spring he began working on a trial basis with Safin, who, like him, is a Russian with fearsome baseline power who spent much of his time on court teetering on the cusp of self-destruction. They also share origins in the same tennis club in Moscow, and both moved on to Spain to continue their training.

Rublev explained that meeting Safin for a conversation by the pool in 2024 helped him exit his spirals of anxiety. “Because I was going in circles, all over and all over, and I didn’t know how to go out from this circle—he helped me to realize why everything was happening to me,” Rublev said in a recent documentary produced by the tour. “He showed me the door.”

We’re still in the early days, but it appears that Rublev has emerged from that door much happier. When I saw how giddy Rublev got at the mere mention of Safin’s name, in Monte Carlo, when they were at the start of their collaboration, it already felt like a triumph. Rublev has since resolved to “achieve as best as I can, but in a healthy way, not in a struggle way.” But being a well-adjusted person and being a successful tennis player are not necessarily correlated. Would Rublev’s results suffer, if he didn’t?

So far, so good. He’s had a decent season. This week at Wimbledon he has survived two high-stress, tiebreak-stuffed matches. In his second-round win over the big-serving Lloyd Harris, Rublev even demonstrated rare flair at the net, winning 23 of his 26 forays there. He said that he knew he should be going to the net more often to finish points, but he previously lacked the confidence. Again he credited Safin: “His confidence straightway gives you confidence as well.”

Rublev won a painless third round against Adrian Mannarino on Friday to earn a spot in the fourth round. His likely opponent there, and the only other seed remaining in their quarter, is Alcaraz. If he can somehow find a way through, this could be a reformed Rublev’s best chance yet to make that long-awaited semifinal. He might even enjoy himself.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Tears of a Clown

Tears of a Clown

Tears of a Clown

For Sascha Bublik at Wimbledon, anything can happen.

For Sascha Bublik at Wimbledon, anything can happen.

By Giri Nathan

June 27, 2025

Sascha Bublik during his winning campaign at Halle. // Getty

Sascha Bublik during his winning campaign at Halle. // Getty

On June 19, Jannik Sinner shocked the world, or at least me, a person who’d spent the past year thinking I had him mostly figured out. The No. 1 player in the world released a musical collaboration with the singer Andrea Boccelli. The world-famous tenor delivers his operatic swells in Italian, and Sinner offers wooden bits of spoken word in English. The tennis player opens the song with this invaluable wisdom: “In our lives there will always be many first times. All you have to do is, is [sic] to be yourself.”

Nobody on the ATP follows that maxim—be yourself—more faithfully than Sascha Bublik, the shaggy, smirking showman who represents Kazakhstan. His tennis is an unabashed reflection of his personality: expressive, trollish, darkly comic. He is a tall servebot that has been augmented with surprisingly soft touch. He has a taste for drop shots and trick shots, and a tendency to tank sets or even entire matches; he likes to talk about how much he values his life outside of tennis and doesn’t want to sacrifice too much at the altar of his career. He speaks with awe about the inhuman work ethic of the very top players, and clearly cherishes his own humanness. That archetype might sound a little familiar to you, and yes, he is basically a Nick Kyrgios without the baggage and with an active ATP career. On the same day that Sinner made his musical debut about being oneself, Bublik, always himself, managed to upset the top seed and defending champion at Halle in three sets.

Bublik can beat pretty much anyone if he’s having a good day and they’re having a bad day. But Jannik Sinner has effectively purged bad days from his tennis life. It was the first time since August 2023 that Sinner had lost to a player ranked outside the top 20. It was also the first time since August 2024 that a human being not named Carlos Alcaraz had managed to beat him. For Bublik, this was a career-best upset. He had a dozen top 10 wins but had never before beaten the tour’s No. 1 player. Barely a month earlier, Bublik had been routed by Sinner in straight sets and wrote sarcastically on Instagram: “I almost got him guys.”

After their match in Halle, he offered a pleasant update: “I got him guys.”

Bublik, rarely blessed with consistency, kept marching along after the upset, beating Tomas Machac, Karen Khachanov, and even Daniil Medvedev to reclaim the Halle title that he’d won in 2023. “From the mental point of view, that’s the toughest match I ever played in my life,” said Bublik after the final. In his six previous matches against Medvedev, he had won just one set. “I have never beaten Daniil. He’s a super tough player to play, especially with my game style, and today everything clicked in mentally and physically.”

It has been a season of renewal for the 28-year-old Bublik, who said he considered quitting tennis around this time last year. As recently as this March, he had lost 18 of his previous 22 matches. He fell to No. 82 in the world after Indian Wells. His reasonably secure top-40ish career was in peril. As with so many players, dropping down a rung of competition helped him rebuild some form. His fortunes began to turn at the Challenger in Phoenix, where he made the final. During the clay season, typically his most wretched stretch of the calendar, he picked up a Challenger title in Turin. Clay season concluded with perhaps the most miraculous moment of his career to date: At Roland-Garros, he made his first Slam quarterfinal, beating top 10 seeds Alex de Minaur and then Jack Draper, after which he wept and savored the applause of the crowd. This longtime jester was now taking part in disorientingly sincere interviews about seizing the moment. “You know, sometimes in life there is only one chance, and I had a feeling like that was mine,” Bublik said after the fourth-round Draper win at Roland-Garros. “I couldn’t let it slip. So, standing here, this is the best moment of my life. Period.” I received texts from friends who were enjoying their first-ever exposure to Bublik. And it must have been nice. But those tears were even richer, emotionally, if you’d witnessed the dozens of clownish episodes in the years leading up to that point. (I highly recommend his conversation with Casper Ruud and Benoit Paire, and in particular his phrase “Check the fact sheet,” if you want a better sense of Bublik’s life philosophy.)

That life-peak run at Roland-Garros was ended unceremoniously by Sinner; Bublik has already exacted his revenge on grass. Now he is about to enter Wimbledon as a No. 28 seed that no player wants to see in his draw. Bublik’s best surface is grass, where his big serves and skidding off-speed shots grow more lethal. In his runner-up speech at Halle, Medvedev openly asked his peer to eliminate Sinner or Alcaraz from the Wimbledon draw, opening things up for everyone else’s sake. On the lawns of southwest London, Bublik could sputter out in round 1, or he could defeat two top 10 players. Both outcomes feel equally possible to me at this moment. Therein lies the Bublik magic.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Late to the Ball

Late To the Ball

Late To the Ball

Tatjana Maria, Amanda Anisimova, and the triumph of the never-too-late attitude.

Tatjana Maria, Amanda Anisimova, and the triumph of the never-too-late attitude.

By Carole Bouchard

June 19, 2025

It was a big week at Queen's for Tat Maria and Amanda Anisimova. // Getty

It was a big week at Queen's for Tat Maria and Amanda Anisimova. // Getty

Tatjana Maria and Amanda Anisimova launched their grass seasons at the Queen’s Club by showing again that it’s never too late to win big, and never too late to reset your career.

The grass may host a blink-and-you-miss-it season, but it always delivers on the drama and the storylines, and it lived up to its billing in its first week. Women’s tennis was back at Queen’s for the first time since 1974, and the players returned in style, giving tennis a fairy-tale ending. Disney is calling, wanting a word with Tatjana Maria.

Maria, 37 and ranked 86th in the world, hadn’t won a single first-round match in her previous nine tournaments when she entered qualifying at Queen’s. Sure, we knew her game was perfectly suited for grass, with her sharp backhand slice and her fondness for the net, but it seemed to many that her incredible run to the semifinals at Wimbledon in 2022 was a result plucked from a bygone era. Unbeknownst to the rest of the field at Queen’s, Maria was about to tear through the draw, clinching her fourth title and reminding everyone she was still an opponent’s nightmare on grass.

Maria’s win was an even more poignant story as it came against former wunderkind Amanda Anisimova. Two very different career paths, but the same story, where success only comes when the player is ready. Anisimova, now 23, reached the semifinals at Roland-Garros in 2019 when she was just 17. She had it all: the power, one of the sweetest backhands in the game, and loads of charisma. But life came for her the same year, with the death of her father. And then came her struggles. Anisimova lost her way, despite finding moments of occasional grace, such as her run to the second week at the Australian Open, in 2022, with coach Darren Cahill, and to the quarterfinals at Wimbledon the same year. Still, tennis lost Anisimova when, mentally drained, she decided to take a break in 2023.

Yet, the same way Tatjana Maria found her best game in her 30s, Anisimova, thanks to her run at Queen’s, has reached her highest ranking to date (13th), launching a kind of second career in the process.

While away from tennis, Anisimova went to college, enjoyed a normal life, learned to paint, and only then came back. Because she wanted to, not because she felt she had to. It has taken some time to pay off, and some more time for her body to adjust to the rigors of the tour, but this year she won her first WTA 1000 title in Doha and advanced again to the second week at Roland-Garros. She’s still not as consistent as we’d like, but she’s finally happy to be out there. Will getting to the final at the Queen’s after beating Zheng Qinwen for the first time be a trigger for a deep run at Wimbledon? Let’s see.

Will Queen’s winner Tatjana Maria be propelled to another epic? Maybe. She is nowadays talked about mostly for her longevity and taken as an example of how to have it all, having had two kids by the time she semifinaled at Wimbledon. Sure, before her there was Kim Clijsters, but if you looked for a player who was not a star to give guidance to the field, you always came back to Maria. The German can be seen all season long with her husband/coach and kids in tow, a smile on her face, fire in the racquet.

“It’s incredible to see what she’s doing, and her family is so cute, seeing her kids coming everywhere,” said Anisimova, who would be Maria’s last victim (6–3, 6–4). It’s not just that Maria became the oldest player to win a WTA event. It’s not just that she was on that dreadful nine-first-round loss streak before arriving in West London. And it’s not about what it says about her mental strength that she still wants to go through it all. It’s mostly about who she beat on the way to that title.

After winning three matches in qualies, Maria had to go through four top 20 players to get her hands on the trophy. The lowest-ranked player she faced in the main draw was Canadian Leylah Fernandez (no slouch at 30th in the world). Besides Leylah, Maria went through two more Grand Slam finalists (Karolina Muchova and Elena Rybakina), the reigning Australian Open champion (Madison Keys), and an on-the-rise-again, 14-years-her junior Amanda Anisimova. How many sets were lost in seven matches? One.

“I’m a good example that even at my age, you can still win big trophies,” Maria told the press after the final. “I’m super proud of myself that I could win this tournament because actually, I always believed in it, and my husband too. That’s why we kept going.” Maria winning at the Queen’s, 51 years after the last women’s match was played there, with a throwback game, is quite the wink from history. It’s also a great lesson for the next generations who, for some impossible-to-understand reason, have decided it wasn’t worth it to get a decent slice. (And it’s not even a shot of the past: Just ask Ash Barty!)

“Grass is perfect for my slice,” said Maria. “I am serving well, I can play a lot of slice, I can go to the net. I can play exactly how I would like to play, and the surface takes every single thing from it. It’s a perfect fit for my game. It actually helps me that nobody plays my style, and everybody has to get used to playing against me. Of course, my game on grass, nobody wants to play me, which is an advantage,” she said after cruising through the draw in London.

“Just not something you’re used to,” Anisimova said of Maria’s playing style. “I mean, in most of my matches, I’m not getting a slice after every single ball. It’s definitely different.” Why not try to take something from it? Imagine the power of Anisimova with a strong slice in her toolbox. The only top player of this next generation who has really worked to add other weapons to her big-hitting game is Aryna Sabalenka, and look what that’s done for her career.

Tatjana Maria winning in London is also a reminder that maybe more players should acquire a slice. And a drop shot. And a good volley. It’s never too late to win the biggest title in your career, to get that career back on track, to add more layers to your game, to shine. Tatjana Maria and Amanda Anisimova were two faces of the same tennis coin throughout the week at the Queen’s, proving, in their own ways, it’s never too late to find your form.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Wonderful Scenes

Wonderful Scenes

Wonderful Scenes

Tam O’Shaughnessy talks tennis, NASA and Sally.

Tam O’Shaughnessy talks tennis, NASA and Sally.

By Patrick Sauer

June 18 2025

Tam O’Shaughnessy in London, 1971. // Getty.

Tam O’Shaughnessy in London, 1971. // Getty

It’s as obvious as the moon in the night sky: Neil Armstrong’s pitch-perfect ode to “a small step for man” and a “giant leap for mankind” is on the short list of the greatest American quotes ever uttered. The brilliance in his poetic brevity will live forever, but he’s not the only astronaut to deliver a profound message from the heavens. For sheer out-of-this-world oddness, a new celestial laureate must be recognized: Dr. Sally K. Ride, America’s First Lady of Space. Gazing back at the home planet from the Challenger space shuttle, she points out the Himalayas and the coral reefs off Australia, notes how the stellar perspective has given her a deeper understanding of how fragile existence is, and then adds a beautiful note, equal parts Neil and Louis Armstrong.

You can look at Earth’s horizon, see this really thin royal blue line, and realize it’s Earth’s atmosphere. And that’s all there is of it. It’s about as thick as the fuzz on a tennis ball.

Given the monumental circumstances, it’s wild that Ride’s thoughts went to an expression that is not only not a cliché, but one that turns up exactly zero Google search returns. To come up with a “Fuzzy Dunlop” during that singular moment of awe shows how central tennis was to her life. It’s one of a handful of captivating throughlines thoroughly explored and dissected in Sally, a new documentary from filmmaker Cristina Costantini streaming on Disney and Hulu.

The heart and soul of Sally is Ride’s partner of 27 years, Tam O’Shaughnessy. They first met at a middle-school tennis tournament, reconnected around the time of the 1983 Cape Canaveral launch, and went on to cofound Sally Ride Science, a program of STEM education designed primarily for girls based out of UC San Diego. Sally is a queer love letter, but it doesn’t hold back on everything Ride sacrificed for her NASA career, including public acknowledgment of their relationship. It only came to light when O’Shaughnessy wrote Ride’s obituary following her 2012 death from pancreatic cancer. The push and pull of being a trailblazing public astronaut and a closeted private individual was never resolved and nearly did the couple in. As O’Shaughnessy says in the film, “It hurt me, but I’m not sure it hurt Sally. She didn’t care about such things.”

Be assured, though, neither Dr. Ride the person nor Sally the documentary is a downer for long. There are too many moments of sheer joy on the courts, in NASA trainings, orbiting the planet, and in tender moments between Sally and Tam—my personal favorite being the time they got all horned up and frisky looking at fungi under a laboratory microscope, culminating in O’Shaughnessy’s posthumous acceptance of Dr. Ride’s Presidential Medal of Freedom from Barack Obama, as the first woman to accept the award on behalf of her same-sex partner.

O’Shaughnessy, an award-winning children’s science author and educator, spoke to The Second Serve about her brief professional Virginia Slims career, her and Sally’s friendship with Billie Jean King, Ride’s bravery in the wake of the space shuttle tragedies, and the sun-kissed beauty of her young romantic tennis rival.

Let’s start with tennis. How did you get into the game, and how did your professional career go?

I grew up in Southern California in the ’60s, which was a golden era of tennis, with so many of the great players—men and women—playing and practicing at the Los Angeles Tennis Club and other area tournaments. I started at 10 and got to see up close what championship tennis looks like. I fell hard for the game, began playing rinky-dink junior tournaments, and just got better and better, which was the same for Sally. We first met as young girls on a boiling-hot day in a tennis tournament line. She was a highly skilled, fierce player.

At 13, I played in a doubles match with Billie Jean King, and she became my coach and our lifelong friend. I was nationally ranked as an amateur and decided to try the pros, which happened to coincide with this incredibly neat new thing, the Virginia Slims circuit. It was really hard making the jump. You think you’re a hotshot, and then everyone is so talented and athletic. I didn’t have a great career, but I was there, and I competed.

Any match or tournament that sticks out in your mind?

In 1972, I played both singles and doubles at Wimbledon. I lost early in both, so I’m not sure that counts as memorable. To get into Wimbledon, I had to go through a qualifier at the Roehampton Club in London, which had the worst grass courts on earth. It felt like running through a rolling series of moguls. I had to win three matches in three days, which was a crazy experience, but it got me in the main draw. I was so honored to set foot on the Wimbledon courts.

Looking back, what did you get out of your tennis years?

The thing about tennis and sports—or endeavors like music, art, dance, whatever—is it teaches you things you might not even necessarily be aware of. By zeroing in on tennis, I learned discipline, which was applicable to pursuits throughout my life. I also came to understand how important and generous good coaches are. As a kid, I was so lucky to learn from Billie Jean and Dr. Walter Johnson, who coached Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe. He also founded the American Tennis Association’s junior development program back when the USTA wouldn’t allow Black kids to play. I played in a few ATA tournaments, which were so much fun. Dr. Johnson didn’t care where you came from, what your background was; all he wanted was tennis to be for everyone. The ATA was an impressive organization. Dr. Johnson was ahead of his time.

In Sally, you say the women on the Virginia Slims circuit were open-minded, and who you were dating or sleeping with was irrelevant. Given how early on in the gay rights movement it was, how important was that experience to you as a young woman?

Well, quite frankly, there weren’t that many queer women on the circuit—most players were straight. But because we had this common thing of tennis, which we were all trying to master against one another, it gave us a unified sense of purpose in many ways. We were also always together, practicing, traveling, going out to eat, etc. Nobody had an entourage or unlimited spending money, so we were a tight-knit bunch. In the early days, people got along, not that there weren’t fights and jealousies and all sorts of things.

Like, say, a Margaret Court?

Yes, every once in a while there was a Margaret Court type, but it was the exception. When I realized I was attracted to women, I felt like I didn’t have anything to really worry about on the circuit. It was a nice way to develop a sense of self as a young person.

In the documentary, Billie Jean King says that after she was outed in 1981, Ride saw the backlash, media storm, and loss of endorsements she faced and understandably decided to keep her true self locked away to not jeopardize her NASA standing. Do you think Sally would’ve done anything differently if she had had an experience similar to yours?

Sally grew up in a family that loved and encouraged her but never talked about personal things, ever. Being private was part of Sally’s nature; it didn’t really have to do with being an astronaut. I’m sure if she had been in the open, welcoming environment I found on the circuit, it would have helped shape her, but she kept our relationship private throughout, so I don’t know if anything would’ve gone differently. Over the years, there has been so much progress for the LGBTQ community, but Sally still died three years before gay marriage was legalized. The more these things moved forward, the more comfortable she felt. I think Sally would’ve gotten there. And I would have loved marrying her.

Can you explain how tennis helped Dr. Ride’s journey to space?

Sally would always say that one reason she was selected into the Astronaut Corps in 1978 was her tennis background. It was unique and set her apart from other applicants. Being so physically coordinated goes along well with being an astronaut. Specifically, her game helped her become talented and proficient in her abilities in operating the space shuttle’s robot arm. Once again, tennis provided future skills unrecognized at the time.

There’s a powerful section in Sally following the 1986 Challenger disaster, but there’s no mention of the 2003 Columbia explosion. I’m curious, was Sally’s reaction different the second time?

When Challenger exploded, Sally was completely crushed and numb, blown away that it happened, even though she was one of a handful of astronauts who truly understood the risks. President Reagan asked her to be on the investigation committee, and she played a pivotal role in the public questioning sessions of NASA leadership.

In the footage, she’s a bulldog.

You can see it in Sally’s face, how angry and upset she is. She held NASA’s feet to the fire. As we would all come to learn, NASA made huge mistakes because they got away from the culture of excellence that built the American space program. Sally believed that after the hearings, NASA solved the problems, going back to double-checking every checklist and having reams of data and evidence for making every decision. She was part of the investigation team after Columbia as well and was disillusioned to realize NASA had let the culture lapse, again. It was like leadership had collectively forgotten what happened to the Challenger.

Since you touched on it earlier, with all these aspects of the movie and your life currently under siege, how are you coping?

It’s a dangerous, miserable time. A lot of harm is being done across the board in our country, from immigration to science to education to, of course, the basic rights of human beings who are simply different from another type of person. It’s heartbreaking to me. I have to remind myself, American support for gay rights is around 70 percent, and in my lifetime, we’ve become a more socially just society that believes in the individual rights of other people. I think it’s imperative that institutions with a large platform and some level of power—be it universities, corporations, organizations like NASA, professional sports leagues, the Democratic Party, and so on—rise up, speak their truth, and stand against what’s going on. It’s normal, everyday American citizens who are most adversely affected. We need real leadership. It’s a hard thing to do, but it’s the only way forward.

Personally, I have to take frequent breaks from the news. This is where my love of sports helps. Athletes can be so encouraging, inspiring, and a positive reminder of what’s possible. The French Open has been a welcome respite from all the awfulness.

Let’s end on a happy note: In your mind’s eye, what do you see when I ask you to picture Sally Ride and Tam O’Shaughnessy out on the tennis court?

First off, I picture myself slender and fit again, with brown hair, so I like that. Mainly what I see is a warm, sunny California day out on a hard court, Sally on the other side of the net. She’s wearing some goofy baggy shorts and a white T-shirt. We’re hitting a ball back and forth until Sally starts being silly, rushing to the net and slamming a volley at my feet, just for the fun of it. We’re both laughing. It’s a wonderful scene.

Tam O'Shaughnessy accepts the 2013 Presidential Medal of Freedom on behalf of her late partner, Sally Ride in 2013 in Washington, DC. // Getty.

Tam O'Shaughnessy accepts the 2013 Presidential Medal of Freedom on behalf of her late partner, Sally Ride in 2013 in Washington, DC. // Getty

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Forces of Nature

Forces of Nature

Forces of Nature

Coco Gauff looks to continue to confound on grass.

Coco Gauff looks to continue to confound on grass.

By Giri Nathan

June 13, 2025

Coco Gauff celebrates her Roland-Garros victory. // Sandra Ruhaut, Getty

Coco Gauff celebrates her Roland-Garros victory. // Sandra Ruhaut, Getty

I recently had an eye exam where I had to peer into a device and press a button every single time a pinprick of light appeared anywhere in my field of vision. There were dozens and dozens of those lights flashing on and off, in rapid succession, each one easily identifiable in isolation. But the focus required to identify and respond to each of them, in a timely and accurate fashion, without any false alarms, was surprisingly taxing. I felt myself making the occasional error not because of my eyes—my eyes are working fine, it turned out—but because I was sleepy that day and struggling mightily to stay vigilant about every single pesky, tiny light peppering the field. It was frustrating. Even a little embarrassing. I now wonder if this is how No. 1 seed Aryna Sabalenka felt in her Roland-Garros final against No. 2 seed Coco Gauff on Saturday.

One line you hear often in tennis commentary is the idea that the “ball is on her racquet.” It is used to identify the aggressor in the matchup. The main character, even. She is the proactive player, and the opponent is reactive. She is the one determining her own fate. Every time the ball is sitting on her strings, the question is whether that swing will produce a winner or an error. It’s as though this two-player game has been reduced to the will of a single player. To me the most “ball is on her racquet” matchup in all of tennis is Sabalenka vs. Gauff. It is a match of peerless offense against peerless defense. And this time, just as it did in the 2023 US Open final, defense survived an initial onslaught from offense and then slowly took control of the match. By the end, offense looked hopeless and dysfunctional.

Sabalenka ended the match with just 37 winners to go with her 70 unforced errors. Afterward she seemed to locate the reason for the loss entirely within her own tennis, as if Gauff were just an incidental feature of the match, like a passing cloud. To hear Sabalenka tell it, the wind was a more significant adversary during the final than the human who was the tournament’s No. 2 seed. Sabalenka described herself as “terrible.” She said that Gauff had won the match by “running and playing those high balls from the frame”—shanking the ball, in other words. She also said that Gauff didn’t play all that well: “I think she won the match not because she played incredible; just because I made all of those mistakes from—like, if you look from the outside, kind of like from easy balls.” A day later, she issued a written apology on Instagram.

Personally I enjoy the occasional press conference delivered in the throes of post-match emotion, with plenty of self-flagellation and without much attention paid to etiquette, but these remarks sure did inspire a lot of Discourse. There was the age-old debate about the arbitrary line between “forced” and “unforced” errors; there was a lot of outrage on behalf of the Roland-Garros champion. Here, as always, Gauff has appeared several decades wiser and calmer than everyone doing said Discourse, calmly batting away the various comments from Aryna that were relayed to her. And to take it into pure tennis terms, if I were Coco, I’d be thrilled to learn that the adversary I’d beaten in two Slam finals still hadn’t quite pieced together how I’d done it. That means it could still work again.

In the 2023 US Open final I saw how Gauff’s scrambling defense seemed to shrink the court for Sabalenka. Challenged to keep hitting two or three extra shots in every rally, the mental fatigue accumulated. Sabalenka’s power tennis, which can be flighty even in the best of circumstances, went utterly haywire. It’s not an accident that the match played out this same way in Paris, too. It was by design. You could take my word for it, or you could listen to someone who once lost to a 15-year-old Gauff and has wonderfully articulated what makes her so dangerous. Here’s a bit from Andrea Petkovic’s lovely description of the way Gauff takes away time and space from her opponents: “The unforced errors hit by Coco’s opponents when she’s playing well are actually forced,” she writes. “Except, they are not forced by Coco’s previous shot (which is what usually goes into the forced error statistics) but they are forced by the entirety of her game and presence on the other side of the net and by choices she has made 20 minutes prior to the point of you netting a forehand.”

While I was watching Gauff force these dozens of errors with her consistency, I remembered that the longtime stereotype of American tennis is serve-and-forehand bashers who favor hard courts. And yet, the best American of this generation is a player whose serve and forehand are her most commonly discussed liabilities. And she was winning at the highest level on clay, with sheer court coverage and a sublime backhand. American tennis: not a monolith! Given Gauff’s athletic gifts, her speed and endurance, clay would seem the best surface for her. She might have gotten to this Roland-Garros title sooner were it not for the perennial dominance of Iga Swiatek, who ended her run at this tournament for the past three seasons in a row. Regardless, she finally made good on the prophecy she wrote into her Notes app in 2021: “I had a dream last night that I will win french open.”

Now Gauff moves toward Wimbledon, the one Slam where she has yet to advance past the fourth round, a stage she first reached as a 15-year-old, making her name for the first time. And though she would probably not self-identify as an enthusiast of grass courts, she does have the third-highest win rate on grass among current top 10 players, and the tour’s second-highest grass-specific Elo rating, according to Tennis Abstract. And Wimbledon has been a bit of a free-for-all in recent years. So why not Coco? Maybe she’ll pull it off and then reveal the Post-it note from 2015 predicting it would happen.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

The Final Confessional

The Final Confessional

The Final Confessional

Roscoe Tanner Seeks Redemption.

Roscoe Tanner Seeks Redemption.

By Joel Drucker

June 13 2025

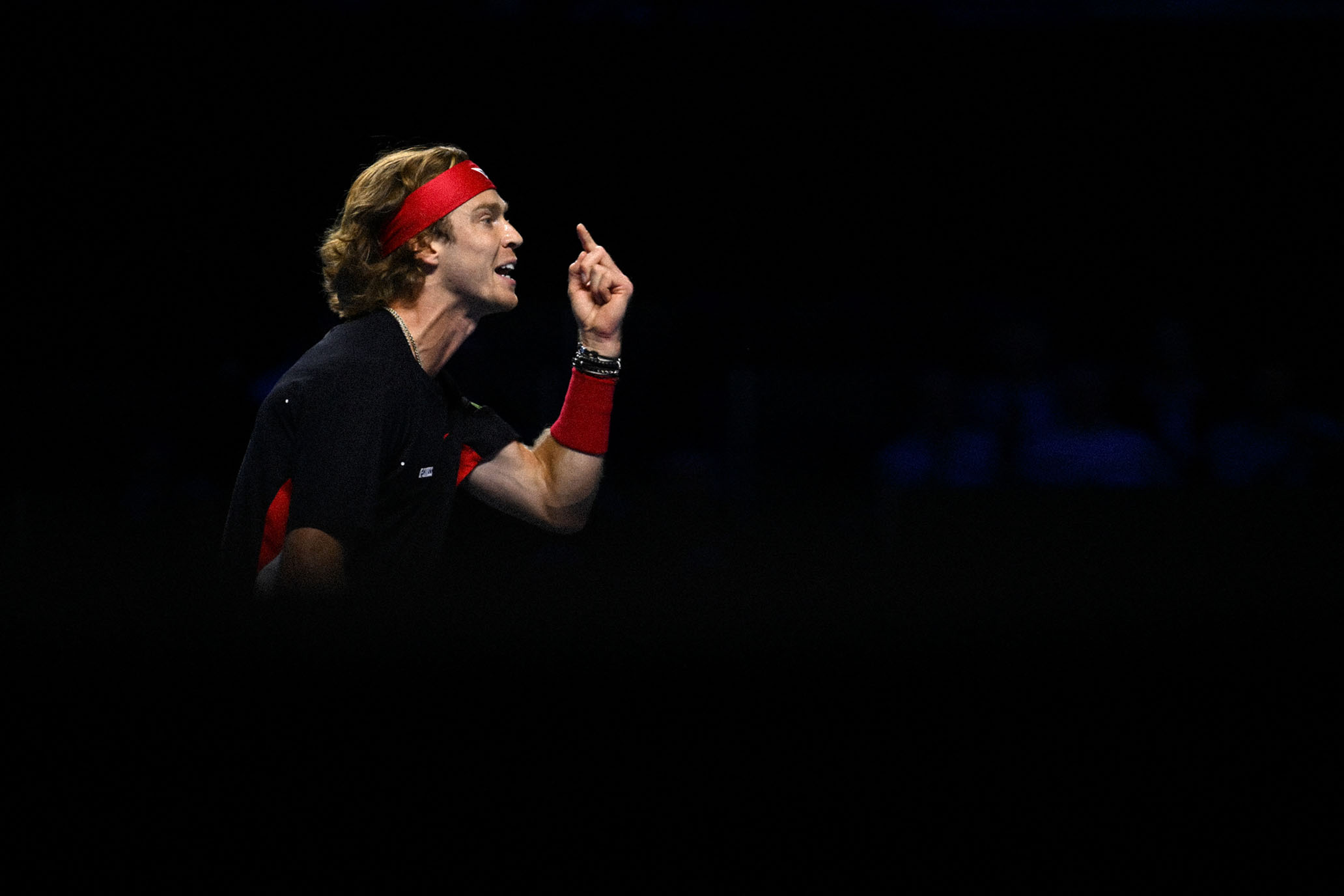

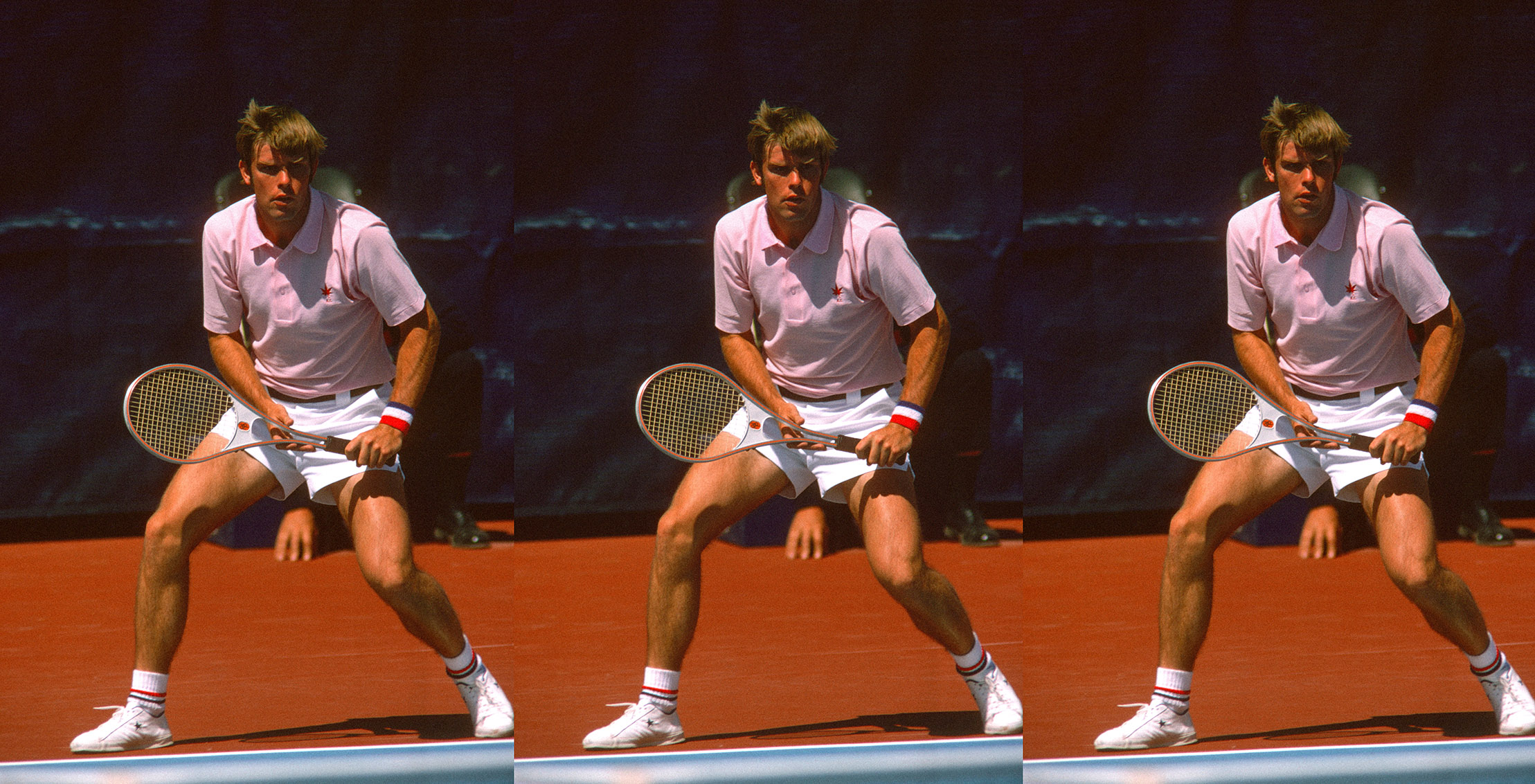

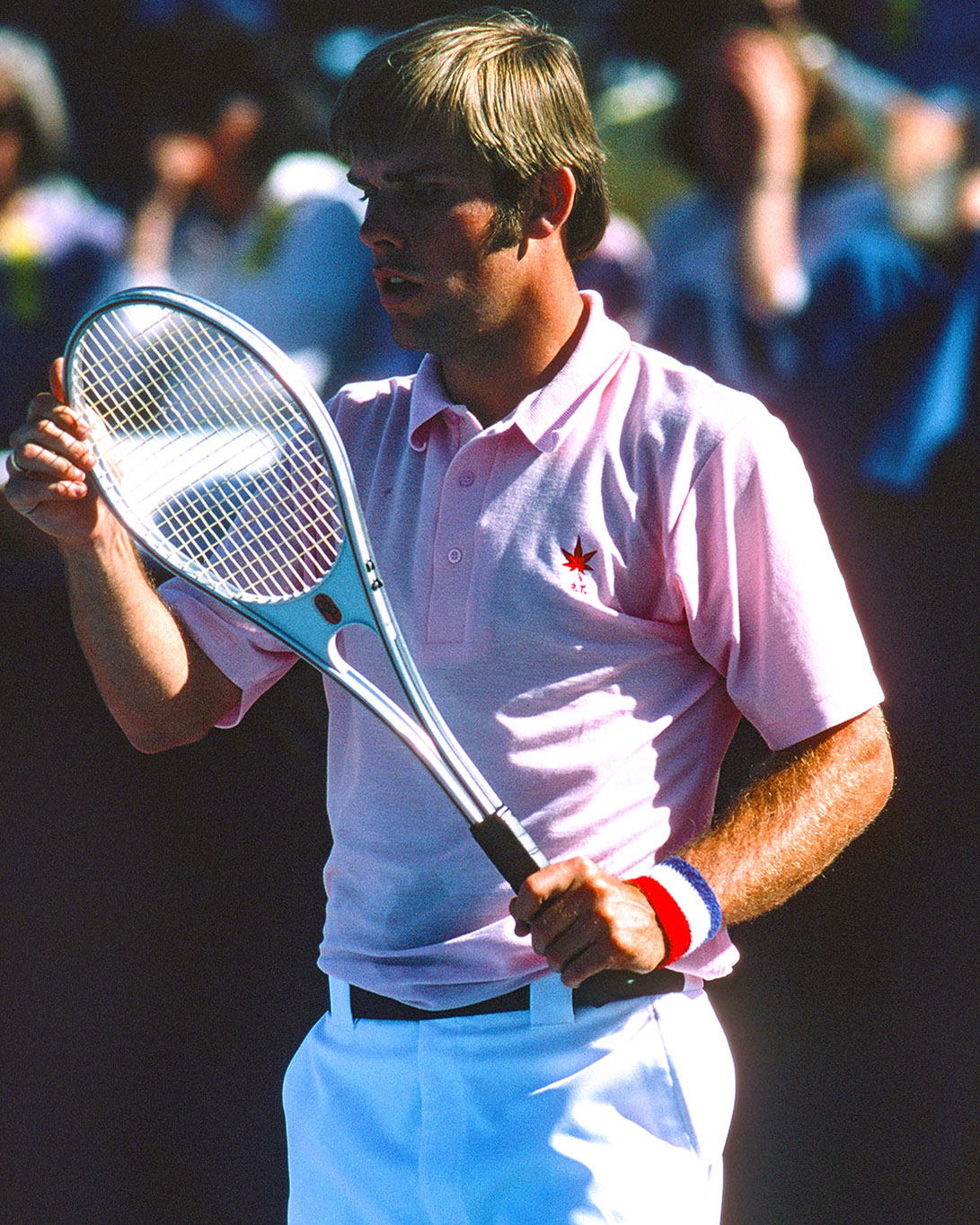

Roscoe Tanner at the American Airlines Tennis Games, Tucson, AZ, 1975.

Roscoe Tanner at the American Airlines Tennis Games, Tucson, AZ, 1975.

Father’s Day promises to be a busy day for Roscoe Tanner. There’s a good chance he’ll go to the church he attends near his home in Orlando. Tanner might also spend time on the tennis courts of several facilities he teaches at roughly 15 hours a week. Perhaps he’ll show a foursome of beginners the fundamentals of doubles. Or help a college player understand the nuances of the serve-volley tactic that took Tanner to a career-high ranking of fourth in the world. And maybe one student will seek to mimic Tanner’s whiplike, left-handed service motion that was once clocked at 153 mph.

But Tanner’s greatest joy on Father’s Day will come from contact with his five daughters—Lauren, Tamara, Anne Monique, Omega, and Lacey. Five women from four mothers, all the children at last on good terms with a man who for decades neglected his spousal and parental responsibilities in ways no one would dare wish upon anyone. From missed child-support payments to bounced checks to multiple jail terms, Tanner has both inflicted pain and paid a heavy price for a series of horrendous choices. He knows this, too, and is now keen to publicly make amends. One step forward: the publication of Tanner’s memoir Second Serve: My Fall From Grace and Road to Reconciliation. “What you’re about to read,” writes Stan Smith in the introduction to Second Serve, “is a brutally honest account of a celebrity athlete who experienced the riches of the world—only to see everything evaporate in his hands.”

“I made some selfish choices,” Tanner told me. “There’s no other way to put it. But I paid for that, and now I’m really lucky that that’s behind me.”

If this sounds familiar, that’s because it is. Twenty years ago, Tanner attempted a similar reinvention. Then, too, there was a book, that one titled Double Fault: My Rise and Fall, and My Road Back. But soon after, Tanner relapsed and was once again arrested. “I don’t want to go through a blow-by-blow description of the last fifteen-plus years of my life,” he writes in Second Serve. “You can do an online search if you’re so inclined.” Estimated to have roughly 30 percent new material, Second Serve addresses Tanner’s desire to live peacefully and ethically. “Some people learn about faith with a nudge, other people get it with a sledgehammer,” said Tanner. “I think I’m closer to the sledgehammer.”

Those who’ve known Tanner for years, some back to childhood days playing in junior tournaments, speak of him mostly with confusion and concern, largely because they have such fond memories of the confident and well-behaved competitor he’d always been. According to former top tenner Brian Gottfried, a Tanner tennis mate since their days as preteens in the early ’60s, “Whenever you played Roscoe, it was always fair and square.”

The world saw the swashbuckling Tanner, too, and never more gloriously than on July 7, 1979, when he entered Centre Court to play the Wimbledon singles final. A heavy underdog versus three-time defending champion Bjorn Borg, Tanner competed brilliantly, jumping off to a two-sets-to-one lead before eventually succumbing, 6–4 in the fifth. It was a first-rate showcase of a man who’d thrown himself into the arena and also emerged triumphant for his effort. As a postscript, Tanner defeated Borg in the quarterfinals of that year’s US Open.

Alas, as graciously as Tanner conducted himself inside the lines, temptation beckoned and captured. “But away from the court,” he writes, “I cheated on [his first wife] Nancy with abandon…. I needed the comfort of a warm embrace. The tour was a lonely place where wolves were looking to devour lambs on the court.” While surely not the first athlete to commit adultery, after his playing career ended, Tanner overextended himself beyond belief, triggering a cascade of financial troubles that in time led to his arrest and imprisonment.

As a player, Tanner could always put setbacks behind him and march forward with his own brand of focus and confidence. “The glass was always overflowing for Roscoe,” said Dick Gould, his coach at Stanford. Tanner, though, recognizes that the laser-like focus that helped him win so many matches wasn’t always so effective elsewhere. “But when you transfer that stubbornness into different things that you think you can get done outside the tennis world,” he said, “it doesn’t necessarily work properly.”

Documenting his time served in a German prison, Tanner writes, “They say that a person can live thirty days without food, three days without water, three minutes without air, but only thirty seconds without hope.” Having bottomed out in prison, Tanner surrendered to a higher power. As he writes, “I leaned over my bed and clasped my hands. ‘Dear Lord,’ I began, ‘I’ve done so many wrongs that I don’t know where to begin. I want you to know that I’m sorry for what my life has become. I repent of my sins and ask you to come into my life now.’”

Tanner writes that, “I’m now in a place where I’m content doing my thing—giving lessons, coaching players, and imparting advice about a game that I’ve loved since I was a little boy.” The same week I read Second Serve, I watched the movie Catch Me if You Can. This is the tale of Frank Abagnale Jr. In his youth, Abagnale forged dozens of checks before being caught by the FBI, imprisoned, and, eventually, hired by the FBI. Who better to detect a forger than a forger?

As I pondered Tanner’s fate, I wondered if, akin to Abagnale, he might find meaning as a source of counsel for youngsters about to embark on the pro tennis journey, active pros faced with many hedonistic options, ex-players uncertain of the next best step. For the sport is filled with dozens of these solitary souls who create pain not just for themselves, but sometimes also for others. And while forgiveness can be granted with words, trust is rebuilt best by deeds.

A common trope is to compare tennis to democracy: a fair form of competition, all outcomes based strictly on the ability of an individual to effectively perform. But there is also a downside to such a singular community. In the 1830s, a Frenchman diplomat named Alexis de Tocqueville came to America. Ironically enough given the case of Tanner, Tocqueville’s nominal mission was to study the American prison system. But his bigger quest—less than 50 years after his homeland’s own revolution—was to understand how democracy played out in this former British colony.

Though tennis as we know it had yet to be invented, Tocqueville anticipated what Tanner must have felt during those many solitary days and nights he spent competing all over the world and then returning to his hotel room. Writing in his iconic book Democracy in America, Tocqueville noted that, “Thus not only does democracy make every man forget his ancestors, but it hides his descendants and separates his contemporaries from him; it throws him back forever upon himself alone and threatens in the end to confine him entirely within the solitude of his own heart.”

“I’ve made some mistakes,” said Tanner. “I paid for it, but let’s all learn from it and go forward.” Now 73 years old, Tanner continues his quest to liberate himself from solitude and cultivate love with the many hearts he shattered and is working earnestly to mend. “I missed a lot of time with them,” Tanner said about his daughters. “On the other hand, I prefer to think about where I am right now, and I’m in a good position with each of them.” On this Father’s Day, light a candle and hope that Roscoe Tanner has indeed authored his final confessional.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Back In Black

Back In Black

Back In Black

Jannik Sinner picks up where he left off.

Jannik Sinner picks up where he left off.

By Giri Nathan

June 6, 2025

Jannik Sinner channels the Official Preppy Handbook during his 2025 Roland-Garros campaign. // Getty

Jannik Sinner channels the Official Preppy Handbook during his 2025 Roland-Garros campaign. // Getty

Jannik Sinner didn’t even want to accept a settlement. Throughout his doping saga, the No. 1 player in the world has proclaimed his innocence. He has said that he took all necessary precautions, and it was only due to the neglect of his support staff that he ended up with the anabolic steroid clostebol in his system. You probably know the story by now, but here’s a reminder of the colorful details. He maintains that his physiotherapist treated a wound on his own finger using a topical spray that contained clostebol; the physiotherapist used that same hand to give Sinner massages; the clostebol got into Sinner’s bloodstream via tiny sores on the player’s skin. The World Anti-Doping Agency, however, sought a ban of one to two years. In the end, Sinner’s legal team convinced the player that it was worth accepting a settlement instead of going back to court, prolonging the process, and risking a much longer ban. And so Jannik, who had just won the Australian Open, took the deal and sat out a three-month chunk of the 2025 season.

It was a convenient chunk of the season, in that Sinner missed no major tournaments, and the first event upon his return to tour would be Rome, where he would enjoy the raucous support of his home crowd. But the suspension was also a profoundly strange time in his life. For the first two months of his suspension, Sinner was subject to strict restrictions on what he could do and where he could appear—even as a mere fan. Though he wanted to spend some of his downtime watching his friends compete in motocross and cycling, he learned he was not even allowed to attend official sporting events. As for tennis, he could not train on courts that were associated with the professional tour, or with any national tennis federation, ruling out pretty much all of his usual haunts. He had to seek out private facilities. He also could not train with any active professional players. But like any tennis player, he had to find a suitable partner. Suddenly the world’s top player was in the same conundrum as a weekend warrior looking for a decent hit.

As it turned out, Sinner had received a message from an old acquaintance: Roberto Marcora, the former world No. 150, who is 12 years his elder and long gone from the tour. Marcora half-jokingly offered his services as a sparring partner. Soon enough, Sinner’s team reached out to him, and they weren’t joking at all. Marcora’s name had to be submitted to WADA for official approval. Because he’d last played professionally at Indian Wells in 2023, Marcora was deemed inactive by the authorities, and they were good to go. In an interview with TennisTalker, Marcora described hitting with an even more advanced version of the kid who had already beaten him in a Challenger final back when Jannik was 17. He said it felt like practicing with Djokovic, but with more power.

After April 13, some of the suspension restrictions were relaxed. Sinner could train with his old pals again. A few days later he was seen hitting with Jack Draper, who was in the midst of a breakout season. The following week, Draper blazed to the final in Madrid, but Sinner was still watching the tour from afar. He made his official return to competition in Rome. In a press conference before the tournament, Sinner did something that shocked me more than any drug test results could. This strenuously private man offered an unprompted update on his romantic life. He’d recently been photographed with the model Lara Lieto, but he took a moment to assure the assembled press that he was in fact single and ready to mingle: “I was also very surprised to see some pictures, which—nothing serious, let’s say it like this: I’m not in a relationship.” Had someone taken our robotic, reticent Jannik and replaced him with this grinning playboy? Or perhaps he was just feeling a lot freer with the doping stress behind him.

Back on court, Sinner picked up right where he left off: beating everyone in sight. It looked as though the stringent limits of his suspension hadn’t detracted much from his game. He murdered his opponents in a tennis-goth, all-black outfit. “I believe it suits me quite well. I like not the yellow and orange and these very bright colors. I like more the darker colors,” he remarked—a clear contrast to his foil Carlos Alcaraz, who often opts for candy-colored kits. On one of his off days during the tournament, Sinner slipped into a dark suit and went to the Vatican to meet the newly named Pope Leo XIV, who loves to play and watch tennis. Sinner gave him a racquet as a gift and offered to volley a bit. The Pope looked around at all the precious objects in the room and decided against it.

The following day, the post-pope Sinner administered a 6–0, 6–1 beatdown to Casper Ruud, the sort of rout you rarely see between two top 10 players. Sinner was so comically, excessively good that Ruud described his play as “next-level shit” and admitted it was “almost fun to witness.” At this point I began to wonder if the three months of rest had in fact given Sinner a leg up on the competition. My speculation cooled off two rounds later, in the final, against Alcaraz, who had dominated the clay season up to that point. This was the most narratively satisfying way for Sinner to return to the tour: a title fight against his archrival, on Alcaraz’s best surface. Sinner stayed neck and neck in the first set, earning himself set points, only to let them slip away. He faded out quickly in the second set. That made four consecutive losses to Alcaraz since the start of 2024. Sinner had suffered only three other losses to the whole rest of the tour during that same span. But he appeared quite happy and relaxed after the match. After all, this was arguably the most challenging test in tennis, and he left it realizing he was “closer than expected” to his goal, despite all that time in exile.

In his runner-up remarks, Sinner paid Alcaraz a compliment: He would be the favorite at Roland-Garros. As we approach the tournament’s last weekend, that may still be true. Alcaraz has lost some sets here and there, but his peak level, seen in his last two rounds against Ben Shelton and Tommy Paul, has been astounding. Sinner, meanwhile, hasn’t dropped a single set through five matches and is barely losing games as of late. They are the No. 1 and No. 2 seeds, sitting on opposite sides of the draw, and they might finally meet in a major final. They have been hurtling toward such a match for quite some time, and it is the most appealing prospect in men’s tennis, though having just spent way too much time thinking about these two dudes, I’m quite biased. The dream final might be just a few days away…unless Novak Djokovic interferes with the proceedings.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

The Devil in the Details

The Devil Is In the Details

The Devil Is In the Details

“To see that your player is improving gives sense to your job,” says Pere Riba, Zheng Qinwen’s coach

“To see that your player is improving gives sense to your job,” says Pere Riba, Zheng Qinwen’s coach

By Carole Bouchard

Jun 2, 2025

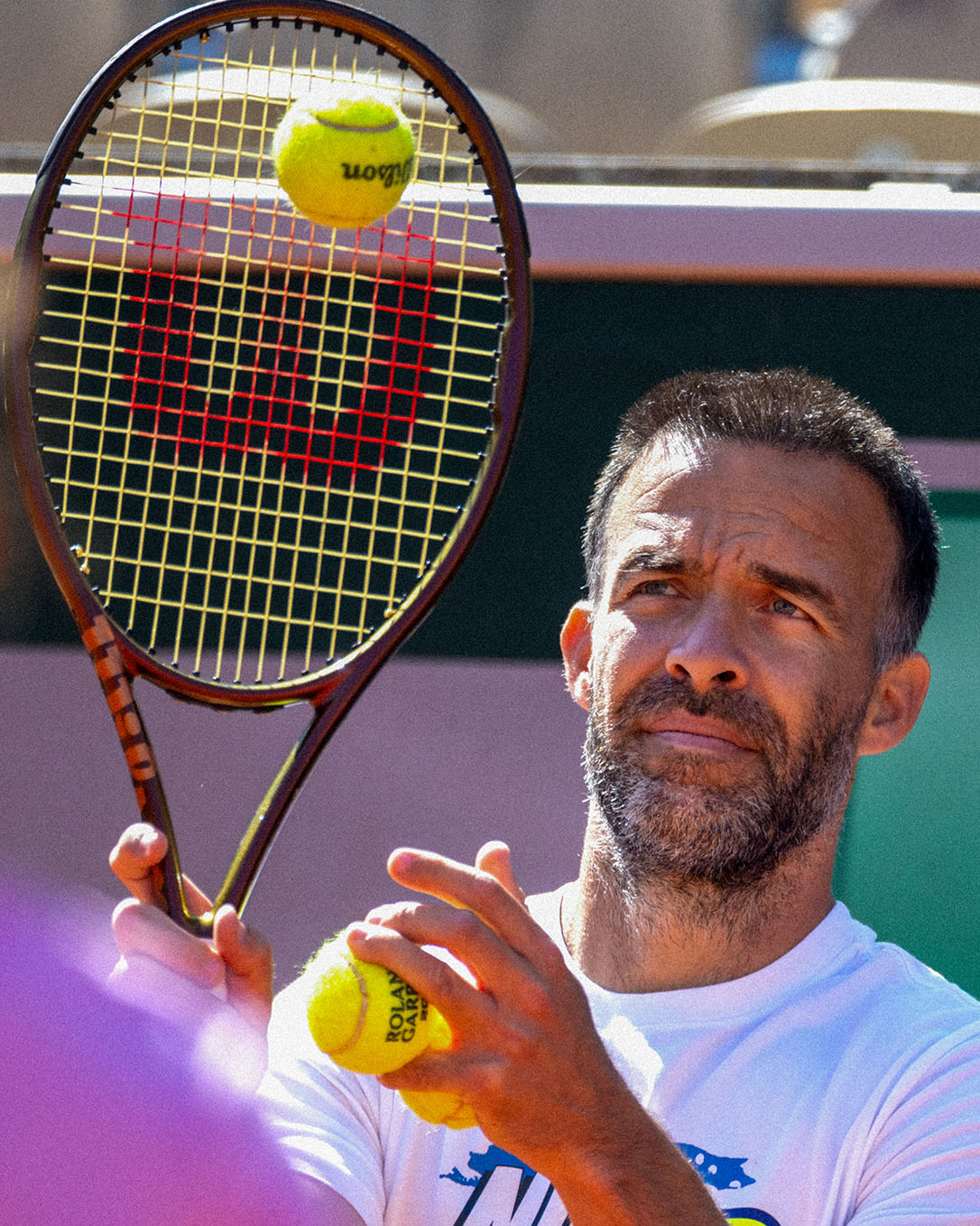

Pere Riba pictured at Roland-Garros this year with his charge, Zheng Qinwen. // Getty

Pere Riba pictured at Roland-Garros this year with his charge, Zheng Qinwen. // Getty

Pere Riba has been working with Zheng Qinwen since she was 18, bringing her to the top 10, a final at the Australian Open in 2024, as well as a gold medal at the Olympics and the finals of the WTA’s year-end championship tournament. In 2023, he was on the team that helped Coco Gauff win the US Open. If there’s someone who knows how to develop a top player’s game, it’s the Spaniard. Carole Bouchard caught up with him at Roland-Garros, where talk of Zheng’s evolution had him all smiles.

Qinwen said that she felt it was time to add things to her game this year, such as coming to the net and hitting drop shots. How did you work on developing her game?

You must always be ready to learn. [At 22, she] is still really young and has a big margin of improvement. If there are things you don’t have in your game or things you have but that need to be improved, you need to do it. It’s always the moment to add things. Of course, she is already one of the best players in the world, and she has amazing potential, but you still have to work on these small details. You want to make the player more complete, because the more tools they have, the easier it is to find a way to win the matches.

It’s challenging to find time to work on the game during the season. How do you manage it?

Yes, well, at least you have a good moment in the preseason to make these changes. But even during the season, you have to choose well to find training blocks. It’s getting tricky nowadays because of the WTA 1000s that are held over two weeks, so you really have to plan well. You need the training blocks to make these little changes happen. Then if you don’t have them, you can also use practice sessions. You set goals. You always ensure that you find an intention in the practice. That is really important to avoid going to the court and then just hitting for the sake of hitting. Of course, you have to do the basics, but then you must find the why. That’s how the player goes to the court with the mindset of, “I want to improve that part of my game.”

I don’t believe in being limited by age in some way. Of course, when they are younger, they can listen a little bit more, but I believe that you can always improve. It doesn’t matter the age—24, 25, 26, 30, or 35—you can always improve. We have the examples of Roger Federer, Novak Djokovic, and Rafael Nadal to prove it. When you see that this can happen—because they did—then why not others? Women’s tennis is the same. They have to be open to improving all the time, and it doesn’t matter if you are No. 1, No. 5, or if you have won a Grand Slam title. You must be open to the idea of continuing to improve, because if not, others will.

Is it easier with Zheng because she is so ambitious and dedicated?

She is truly open to improvement and change. Especially when she believes in it and when she sees that it’s so obvious. I understand that when the player is growing, when the player is getting better, especially in the rankings, sometimes you can doubt about making changes. Everything is working well, right? Everything you are doing is working, and you’re winning a lot of matches; everything seems fine. Yet there are still small things to improve. You must understand that if you improve, you will become a better player and have a greater chance of winning big events, especially when you are young.

It’s a big responsibility when your player is already in the top 10, having played a Grand Slam final and won the gold at the Olympics…

Yes, it is. But in the end, you have to aim as high as you can. In my opinion, she has to aim to be No. 1 and win Slams. If you want to win these events and be at the top, then the process requires these improvements.

I saw her at the net here, and I was like, “Oh, that’s new!”

She’s going more to the net, she’s doing drop shots, she’s opening the court more, she’s serving much better. And still, she can improve many things. But I’m really happy because for a coach to see that your player is improving gives sense to your job. Every year I watch her, she becomes a better player. Results are another thing because sometimes you can do things well and then have one bad day. However, if you take a global look at the work done over the years, you can see that every year she has been better than the previous one. I have a lot of faith in her.

Did you already have a vision for a game early in your collaboration?

I met her when she was 18. I remember that she was ranked 180 and came from juniors. I saw huge potential, but at that moment, it was a different thing: She had good potential on the shot, but there was something in her game patterns that needed work. I love the process that she went through, and you can now see it in the way she uses her heavy forehand. Now she goes to the court, and she so clearly knows the patterns and what she has to do. Now she’s playing with sense. She knows when to attack and when she has to defend. Of course, she needs to improve a lot because everyone can improve, but I’m so happy with the process, seeing how far she’s come since her junior days. It makes me happy to see how she has evolved and how she continues to evolve.

Long-term work is the only thing that can work…

Well, these days it’s not easy to find because young generations don’t have the patience. They want to succeed right now. But they have to believe in that process and show a little bit of patience during the work, even when the result isn’t coming at the moment they’d have wanted it to. You need to allow time for the process you are undertaking, as things will work out in the long term if you do it correctly. It’s going to come.