Coco Gauff vs. Coco Gauff

Coco Gauff vs.

Coco Gauff

Coco Gauff vs. Coco Gauff

The American star is winning ugly at the US Open. But winning.

The American star is winning ugly at the US Open. But winning.

By Giri Nathan

Aug 29, 2025

Coco Gauff walks on court for her second round matchup with Donna Vekic. // Getty

Coco Gauff walks on court for her second round matchup with Donna Vekic. // Getty

For me, the match of the US Open so far was Coco Gauff vs. Ajla Tomljanovic—which was also, to some extent, Coco Gauff vs. Coco Gauff. Which is why it was so compelling. Gauff is an all-world athlete and mental titan who holds two major titles at just age 21; she also happens to struggle with the two central shots of tennis, the serve and the forehand. And when those shots go awry, her matches can leave her fans white-knuckling. Sometimes a match is thrilling because of both the good tennis and the bad tennis it contains. It keeps you guessing which is coming next.

In that match on Tuesday evening, they played several of the longest and most spectacular rallies of the week, as Tomljanovic kept on the pressure with ingenious counterpunching. But lots of the pressure on Gauff was self-inflicted. You’d see her hitting an off-balance forehand off her back foot, and you’d know it’s going to land short in the court. You’d see that second serve ball toss go up, and you’d know that ball is fated for the net. In between those moments, you might also see some of the most fleet-footed defense you’ve ever seen on a tennis court. So it’s a little bit of everything.

Gauff returned to Ashe on Thursday to play her second-round match against Donna Vekic. Here her demon was, once again, the serve. She’s aware it’s an issue. In fact, just days before the US Open began, she hired the biomechanics specialist Gavin MacMillan, who had previously coached Aryna Sabalenka out of her crippling double-fault habit. Gauff was seen on practice courts receiving technical instructions, just ahead of the year’s last major. I imagine it’s a very tricky time to be in one’s head about technique. Whatever the cause, in her second-round match on Thursday, Gauff was broken four times in the first set, hitting seven double faults. She wept during the changeover after one of those breaks of serve. You might imagine that the atmosphere was tense and emotional.

I must clarify what it is actually like to sit in the lower bowl of Arthur Ashe Stadium during the night session, with beautiful, breezy late-summer weather, for a match starring the most beloved American player of the moment. All the elements are in place for an ideal tennis atmosphere. Instead the stadium is filled with an all-encompassing, dull murmur. Ten thousand lukewarm conversations taking place at the same time. The murmur continues during points, after points; it does not discriminate. It is totally indifferent to the tennis match happening below. It sounds like we are not in a stadium but rather in a large cafeteria, or hotel conference room. Sometimes the collective murmur is enough to drown out the sound of the ball. And what good is tennis without its tennis sounds?

It is the oddest atmosphere I’ve ever experienced on a show court at a tennis tournament. Even the fans seated just a few rows away from the hard court are prone to standing up, milling around, posing for photos during the rallies. I can’t remember when exactly it got this way, but it’s been like this for a while now. It feels like an unhappy medium. You get neither the pure silence of Centre Court nor the raucous environment of a normal non-tennis sporting event. You just get this purgatorial murmur. Sometimes I wonder if it’s an acoustics issue; sometimes I wonder if it’s a Honey Deuce issue. Probably a bit of both.

In any case, that’s the environment in which I watched Gauff will her way through a gutsy first set, before putting Vekic away more comfortably in the second set. And then, after the victory, and despite all my complaints I’ve just registered, Gauff started the on-court interview and…sincerely and effusively thanked the crowd. And even cried a bit! So what do I know? Maybe she’s detecting good vibes that I’ve been missing entirely. “I’ve had some tough moments on this court, and you guys pull me through each time,” she said. For the first time all night, with its teary champ on the mic, Arthur Ashe Stadium got loud.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Peaks and Volleys

Mirra Andreeva’s Peaks and Volleys

Mirra Andreeva’s Peaks and Volleys

The teen will arrive at the US Open with neither momentum nor preparation. And that’s OK.

The teen will arrive at the US Open with neither momentum nor preparation. And that’s OK.

By Owen Lewis

Aug 22, 2025

Mirra Andreeva. // David Bartholow

Mirra Andreeva. // David Bartholow

At 18 years old, Mirra Andreeva has already convinced me that when she strikes a lob, no matter how seemingly doomed the point of contact, it will always land in the most awkward imaginable location for the opponent. The first few times I saw her dive-bomb the baseline on the stretch at Indian Wells this year, I figured it was a purple patch. Nobody, not even Andy Murray, had the ability to hit those precarious parabolas with such precision and consistency. By the end of the tournament, I was already sold. Andreeva survived a second-set blowout to beat Iga Swiatek in the third. Her lobs tempted Aryna Sabalenka, the WTA’s most fearsome offensive machine, to smack forehands halfway up the net in the final rather than deal with another one. What couldn’t Andreeva do? I wasn’t sure if this devilish defensive work was calculated or instinctive, but the results were devastating.

After that obliterating triumph in the desert, her second straight WTA 1000 title of the still-young year, Andreeva looked ready to win a major. That defense could unravel the best offenses; Coco Gauff had won the 2023 US Open playing along similar lines. And at times, Andreeva would throw in blazing serves as fast as 126 mph—what?—suggesting that she hadn’t even scraped her ceiling yet.

Since, though, her results have stagnated. A spectacularly sloppy Miami loss to Amanda Anisimova was easy to look beyond; I’d petition to unilaterally ignore the result directly after a taxing tournament run. The BOSS Open, at which Ekaterina Alexandrova crushed Andreeva, didn’t seem sufficiently important to read into. A 7–5, 6–1 defeat to Gauff in Madrid raised an eyebrow: Andreeva had served for the first set, had set points, been broken, then won only one more game. Gauff beat her again in Rome. At Roland-Garros, Andreeva stormed to the quarterfinals without dropping a set. She met home favorite Lois Boisson, who was playing with unanimous crowd support but couldn’t match Andreeva’s complete game. Andreeva, though, buckled under the ferocity of the support for Boisson and lost in straight sets.

It was around then I started thinking that 18-year-olds should not necessarily be subjected to the intense atmospheric pressure at the top of the tour, prodigious talent or not. The forehands and backhands might be there, but what teenager could possibly be prepared for week-in, week-out travel, unrelentingly cumulative physical strain, grass courts, a French audience? In the first quarter of 2022, after Carlos Alcaraz became famous but before he consolidated his obvious talent into big titles, I had the gall to wonder why it was taking him so long. (He set various age-related records that year, won the US Open, and reached No. 1 in the world.) The game was so clearly ready. But teenage players have to worry about being a teenager as well as building a tennis empire.

My friend Vansh Vermani recently suggested to me that the challenge of improving at tennis is akin to ascending a skyscraper first via elevator, then stairs. Talent enables players to take the elevator at first, as far as the halfway point of the building for the most naturally gifted. But due to the structure’s architectural nature, that’s where the elevator tops out, forcing everyone onto the stairs beyond that point. The high stairs are where you’ll find players with perfect baseline games trying to refine their touch, former world No. 1s cooking up ways to get back at the rival who unseated them, hard-court experts translating their movement onto living grass and shifting clay. Even Novak Djokovic is there, now steadily sliding back down after topping out near the building’s apex at his best, stubbornly trying to ascend the steps labeled “reliably beating Rafael Nadal on clay” and “coherent overhead smash.”

Andreeva, to me, disembarked from the elevator after that remarkable Indian Wells run and has been adjusting to the stairs ever since. At the National Bank Open in Montreal, Andreeva failed to win the first set of her match against McCartney Kessler despite leading by a break four separate times. (Even more surprising than that, two of her lobs landed out during the tiebreak.) In a rare moment of imperfect coordination in the second set, she chased a Kessler backhand and couldn’t get there, then took a tumble and came up with an ankle injury and a good cry. She looked like a kid having an awful day. She fought through it to a straight-set loss, then pulled out of Cincinnati.

Andreeva may not be skipping steps yet or even climbing them, but I’d argue these experiences are still valuable. Sometimes it seems more advantageous to peak later in your career rather than as soon as possible. Get there early and you might not know the ropes yet—Roger Federer lost to Rafael Nadal most of the time despite being ranked higher, Jennifer Capriati burned out quickly, Carlos Alcaraz still had the attention span of an over-sugared toddler, Iga Swiatek faced magnified pressure. Jannik Sinner might have been flailing against top players while Alcaraz broke out, but Sinner’s current reign at No. 1 is smoother than Alcaraz’s ever was. Maybe what looks robotic now is just maturity.

What if it pays to eat all the shit before you reach your peak? Say Andreeva had won Roland-Garros on top of those WTA 1000 triumphs earlier in the season. It would have been remarkable, but the attendant rush of fame and obligation might also have sparked a deeper slump than what we’re seeing now. Emma Raducanu seems, finally, to be emerging out from underneath the deleterious effects of her teenage triumph at the 2021 US Open. Winning a major that young may not be worth it if the price is a three-year recovery period.

Andreeva will arrive at the US Open without momentum or preparation outside a brief mixed-doubles run with Daniil Medvedev (though the lack of expectation might prove helpful). She’ll have a distant chance to win it all and a golden opportunity to learn, to feel, to grow. Those things taking time doesn’t mean Andreeva can’t end up right where she wants to eventually, like her lobs.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Changeover

Damage Control

Damage Control

Excerpt: Changeover: A Young Rivalry and a New Era of Men's Tennis.

Excerpt: Changeover: A Young Rivalry and a New Era of Men's Tennis.

By Giri Nathan

Aug 19, 2025

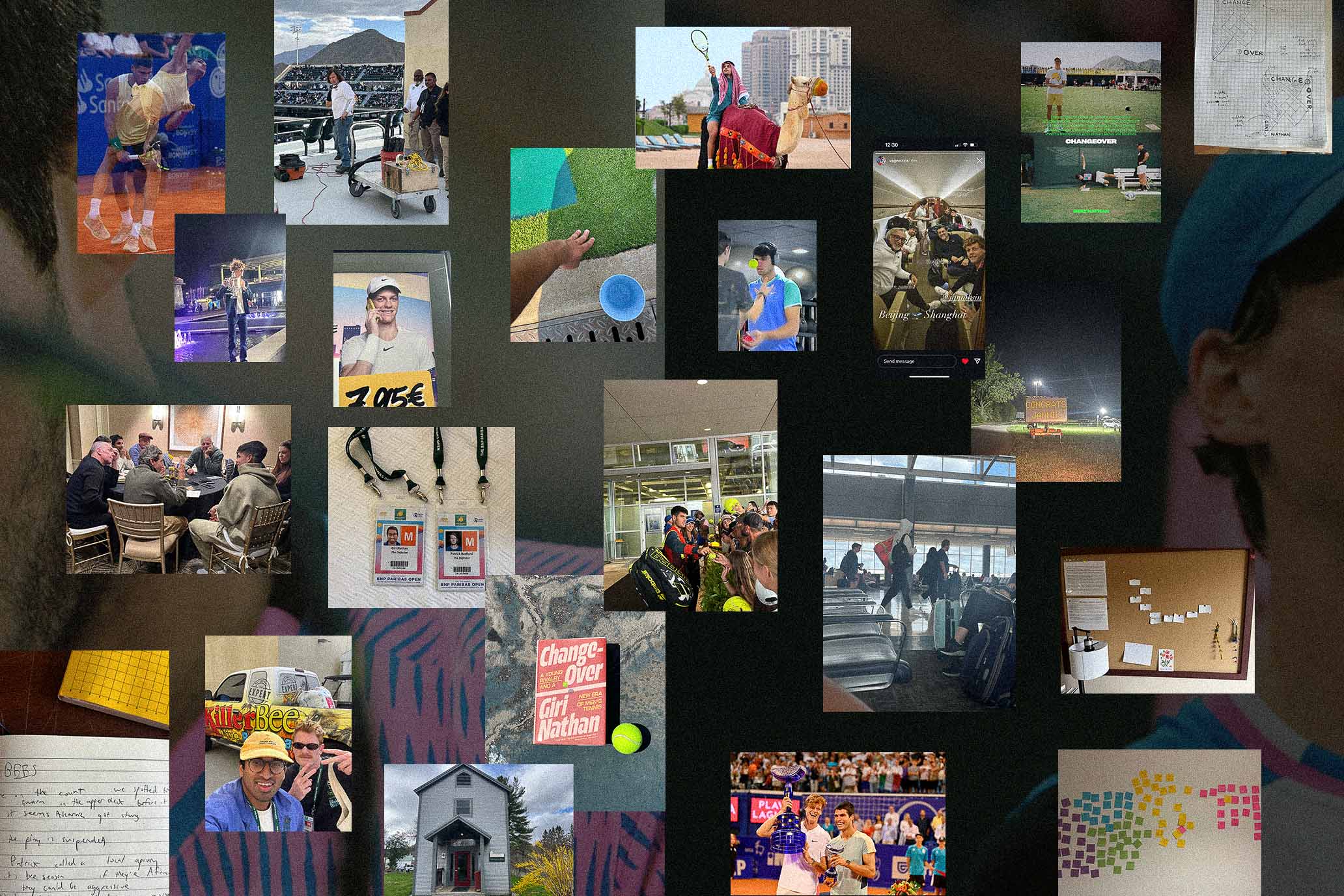

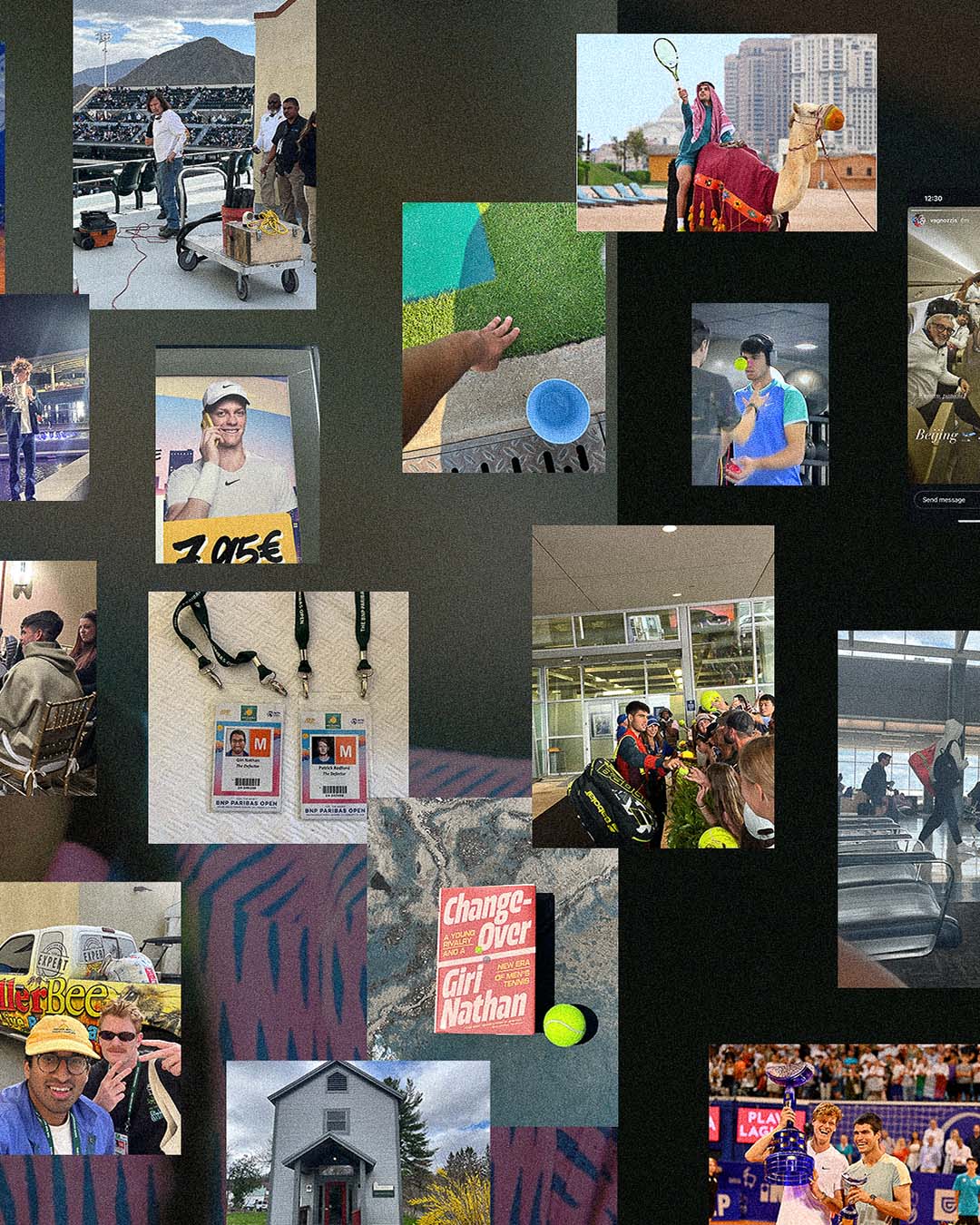

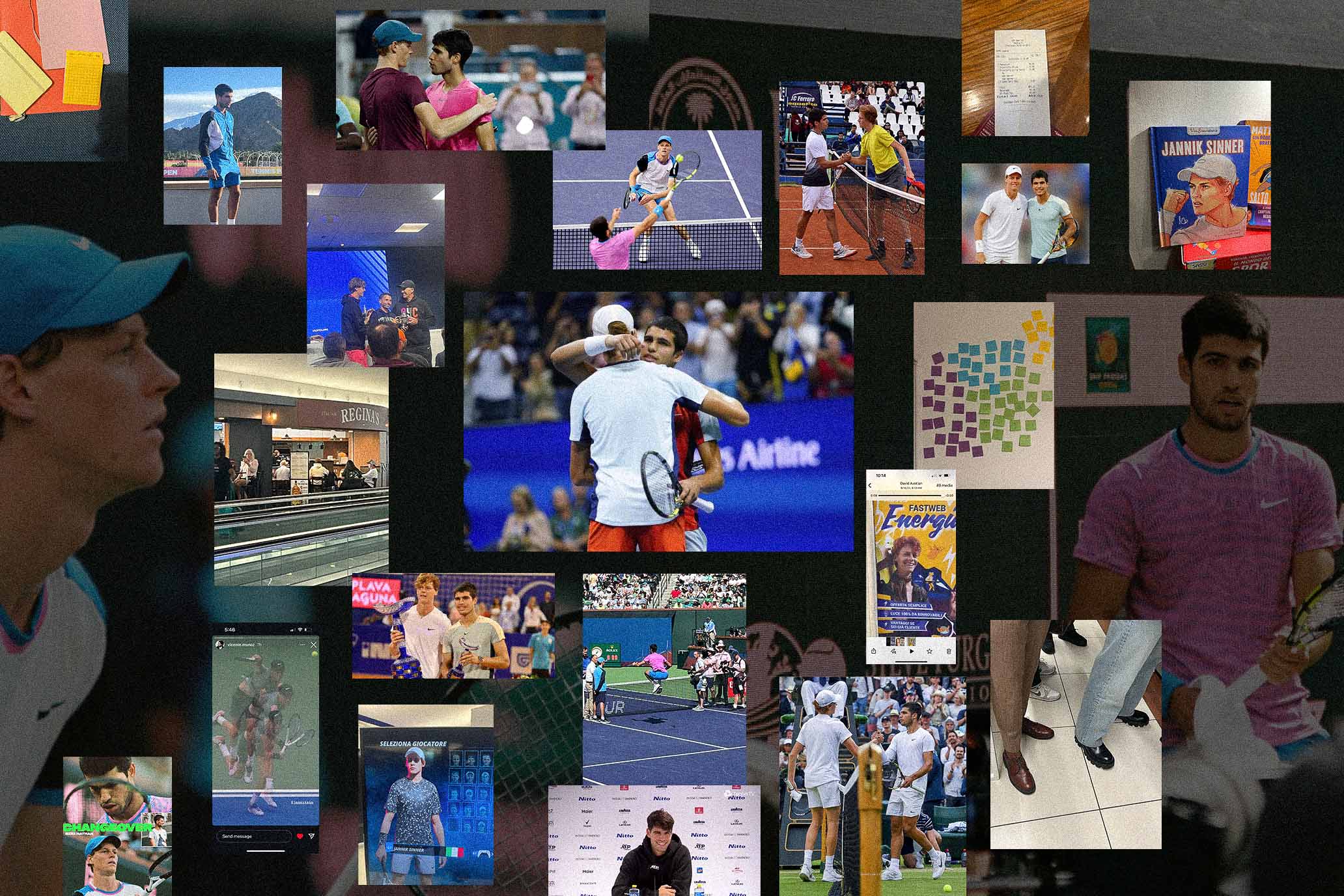

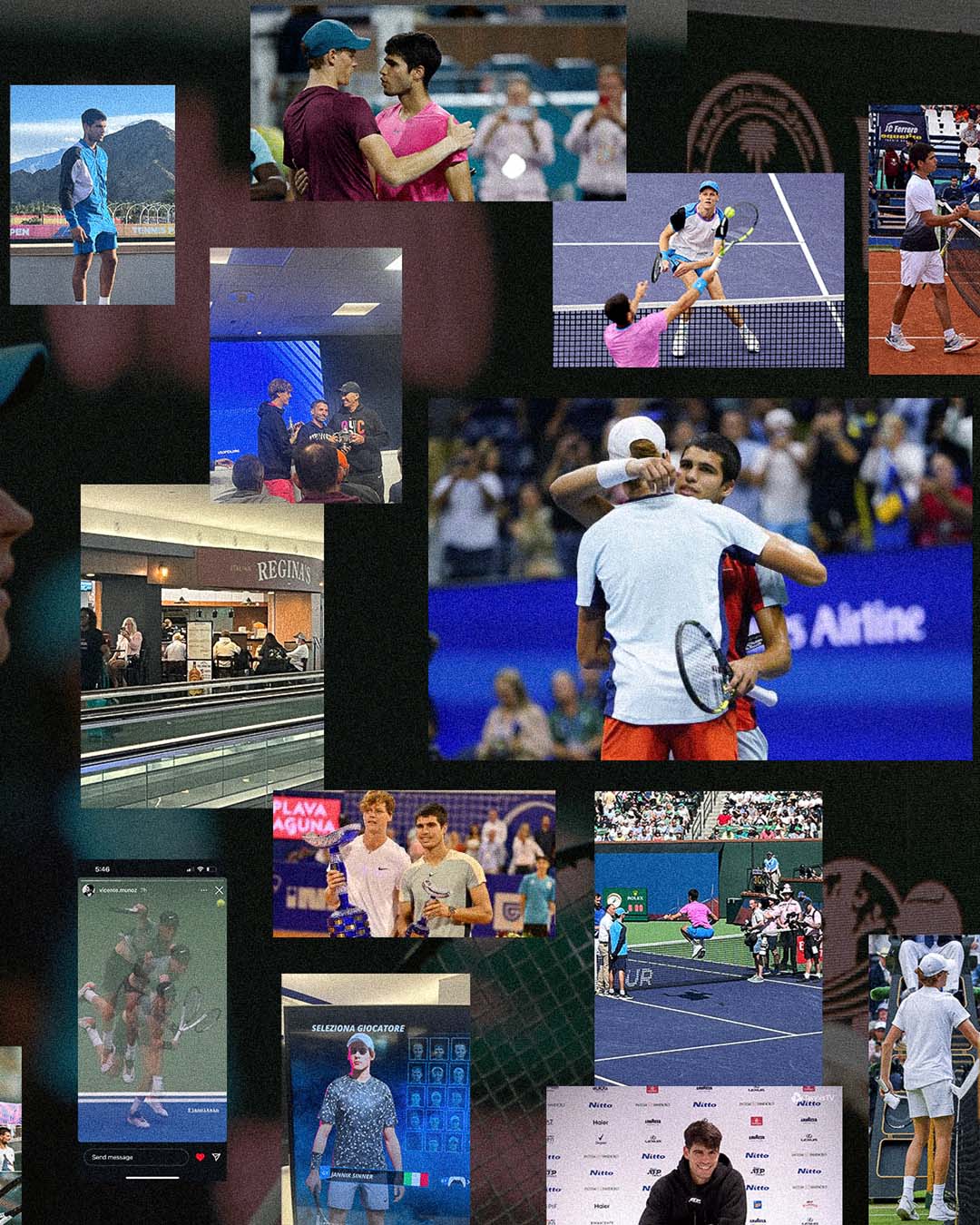

Giri Nathan's mood board for Changeover.

Giri Nathan's mood board for Changeover.

These days, to talk to a player in a truly relaxed state, you often have to catch them at the outset of a tournament, before the churn and toil begin. That hasn’t always been the case. The membrane between journalist and player was more permeable back in the day. The veteran tennis journalist Jon Wertheim told me that at the turn of the millennium, he could speak to Venus Williams privately for half an hour in the middle of a tournament; my eyeballs plopped out onto my keyboard. Curry Kirkpatrick, who wrote fizzy profiles of players for Sports Illustrated throughout the eighties and nineties, told me stories about ambling up to Andre Agassi at a swimming pool and bickering with John McEnroe on a walk after he’d written something not quite to the hothead American’s liking. The notion of a player today submitting themselves to the critical eye of a journalist, for meaningful conversation, was essentially unthinkable. Tournaments have whittled away the zones where players and writers could commingle. Storytelling is consolidated in the hands of the players.

Sports media is dead; most of what’s left is window dressing for online sports gambling firms.

Print journalists have become unnecessary middlemen for athletes who can instantaneously transmit their idle thoughts to fans on social media. To expand his popularity, a player relies not on a ferrety writer, but on a well-cut highlight reel or a high-end photo shoot. I understand the calculus: When your own time becomes so valuable, why give away access to your life story for free? There has to be something in it for them, too. A brief, canned sit-down interview might be an acceptable cost to promote a needy sponsor, or to secure a sumptuous cover shoot, which yields photos that can be tossed on Instagram to slake thirsty fans. The image has fully stomped out the written word in sporting culture, if not culture full stop. Players with enough clout can even partake in another current pastime: the hagiographical docuseries, where the player gets full editorial veto power. As noted, Netflix cameras trailed Alcaraz for chunks of the 2024 season. What we lose, in this new media ecosystem, are the thornier narratives that the players themselves don’t want to share.

Aside from this broader societal shift, there’s also been a tennis specific shift: The athletes have gotten a lot more sophisticated about whom they hire for their “team.” Top-ranked players have become business executives, constantly hiring and replacing personnel. Typically, the team consists of the following. There is the agent, to secure the endorsement deals, sponsorships, and appearance fees. The coach, to hone tactics and technique—sometimes two, with different emphases, as Sinner has in Darren Cahill for the bigger picture and Simone Vagnozzi for the fine details. The strength-and conditioning coach, to keep nudging the body toward its optimal state. The physiotherapist, to help a banged-up body recuperate after matches. There might also be a sports psychologist and a nutritionist. Much of this staff travels the world with the player, and unlike in team sports, where a franchise handles the overhead, players have to pay their employees out of their own earnings. In a 2021 interview with Sports.ru, Andrey Rublev estimated his annual expenses were about $600,000; even that was on a down year for travel, and more than a few players have an even larger full-time staff than his.

The rapid expansion of the player team is a consequence of rapidly increasing prize and sponsor money in the sport. The titles won them glory, and the agents leveraged that glory to win the player even bigger checks. Winning Roland-Garros in June, for example, earned Alcaraz €2.4 million from the tournament. But a few weeks earlier, he had signed a long-term contract with Nike that paid him roughly $15 to $20 million a year, according to the Spanish outlet Relevo. Sinner had signed a similarly structured Nike contract in 2022, about $150 million over 10 years, before he had won much of note. The apparel companies were already flinging around the sorts of sums they had paid to the Big Three. In a famous round of corporate bidding, Roger Federer had been lured away from Nike to Uniqlo with a 10-year, $300 million contract. Even apparel companies outside of sport wanted a piece of the new kids. Sinner became an ambassador for Gucci, and in 2023 the luxury brand had to persuade Wimbledon to permit a brownish duffel bag that broke the tournament’s militant all-white code. The Italian’s leggy frame and glassy expressions hold up surprisingly well in the context of a fashion shoot. Alcaraz’s brawnier build, meanwhile, had him modeling underwear for Calvin Klein.

Armed with these bankrolls, the Big Three could afford to reinvest in personnel to help prolong their careers and earning potential. This became a new template for the present stars to follow. But as the tennis journalist Ben Rothenberg told me, young players ensconced in these huge teams can also become “siloed and isolated,” spending most of their lives around people on their payroll, marinating in a tour culture that is increasingly sterile. The personalities are becoming a little less freewheeling and inquisitive, a little more coddled and calculating. We cherish someone like Daniil Medvedev because he is an outlier to these trends. He seems to be one of the last people speaking his truth at all hours, sometimes to his financial detriment, always to our delight.

There’s a lull before every tournament called “media day.” Players have arrived on the premises, and they’re practicing, but not yet playing official matches. They are thus ripe to be turned into Content. They spend a decent chunk of that day recording clips that will be circulated on social media to promote the tour. Part of the day is set aside for journalists. Select players of interest are trotted out for a casual roundtable discussion, which at the Cincinnati Open was taking place in the dining area of a little golf club across the street from the tournament venue. These discussions, which were each set to last around eight or nine minutes, were also susceptible to starting eight or nine minutes early, as Sinner’s did; the player’s schedule overrules all others’. He popped into the golf club looking tanner than I remembered, as if his skin were bronzing to match his hair, and wearing a white-and-black hoodie that seemed like overkill for the 84-degree afternoon. He talked us through his summer of ailments—hip pain in the clay season, an unnamed illness at Wimbledon that left him woozy, the tonsillitis that knocked him out of the Olympics—and ended with a bit of Zen. “You know, sometimes you have to accept this.” The hip in particular had looked sketchy in his most recent match in Montreal, a loss to Rublev, where Sinner had been clutching at it for the better part of an hour. When I asked if it was still bothering him, he said it wasn’t, and he was “not afraid.”

But he wrapped up on a muted note, as if he just wanted to get some match reps in Ohio to get in shape for the imminent U.S. Open, the year’s last major.

In Cincinnati, Sinner and Alcaraz were the first and second seeds respectively and could meet in the final. Djokovic was still recovering from his Olympic bliss and would not play the role of the chaperone at the teen dance making room for the Holy Spirit between the youthful duo. Alcaraz showed up on media day in the boxy white tee that had become his pre-tournament staple, speaking fondly about the “epic” final he’d lost to Djokovic at last year’s tournament. Asked whether the suburban environs relaxed him, he laughed; this was still a 1000-level tournament, and he was fighting to end the year as the No. 1 player in the world, a race that Sinner still led despite Alcaraz’s rare double at Roland-Garros and Wimbledon.

Alcaraz was asked once again about playing alongside Nadal at the Olympics, and I was vaguely depressed to hear him recycle almost verbatim an answer I’d heard before. I felt for him, and for those trying to coax a tasty quote out of him. Every journalist seemed to want the Nadalcaraz doubles to have been a transformative experience for the junior Spaniard, and while I’m sure it was on some level, it might not have been the Yoda-like transmission of wisdom we hoped to depict it as. Again I was reminded that sports writing isn’t so much tracing the truth as telling a story with a satisfying shape. I could almost mouth the words as Alcaraz repeated what he’d learned from Nadal on court: “Sometimes when we were down, he was there in a positive way, talking to me like, ‘Well, right now they are gonna feel the pressure. We have to just stay there, putting some balls in, trying to get them in trouble.’ Some situations, some things that you probably don’t see—or is difficult to see—he sees very clear.” Alcaraz was always cooperative with reporters, and he didn’t switch on autopilot the way Sinner sometimes did. It was hard to blame a 21-year-old for reusing an old line. Maybe today’s players had reason to prefer recording breezy video clips about who the funniest or most handsome player on tour was, when the alternative was talking to us obsolete scribes with our little recorders.

Click here to order Changeover.

Giri Nathan's mood board for Changeover.

Giri Nathan's mood board for Changeover.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

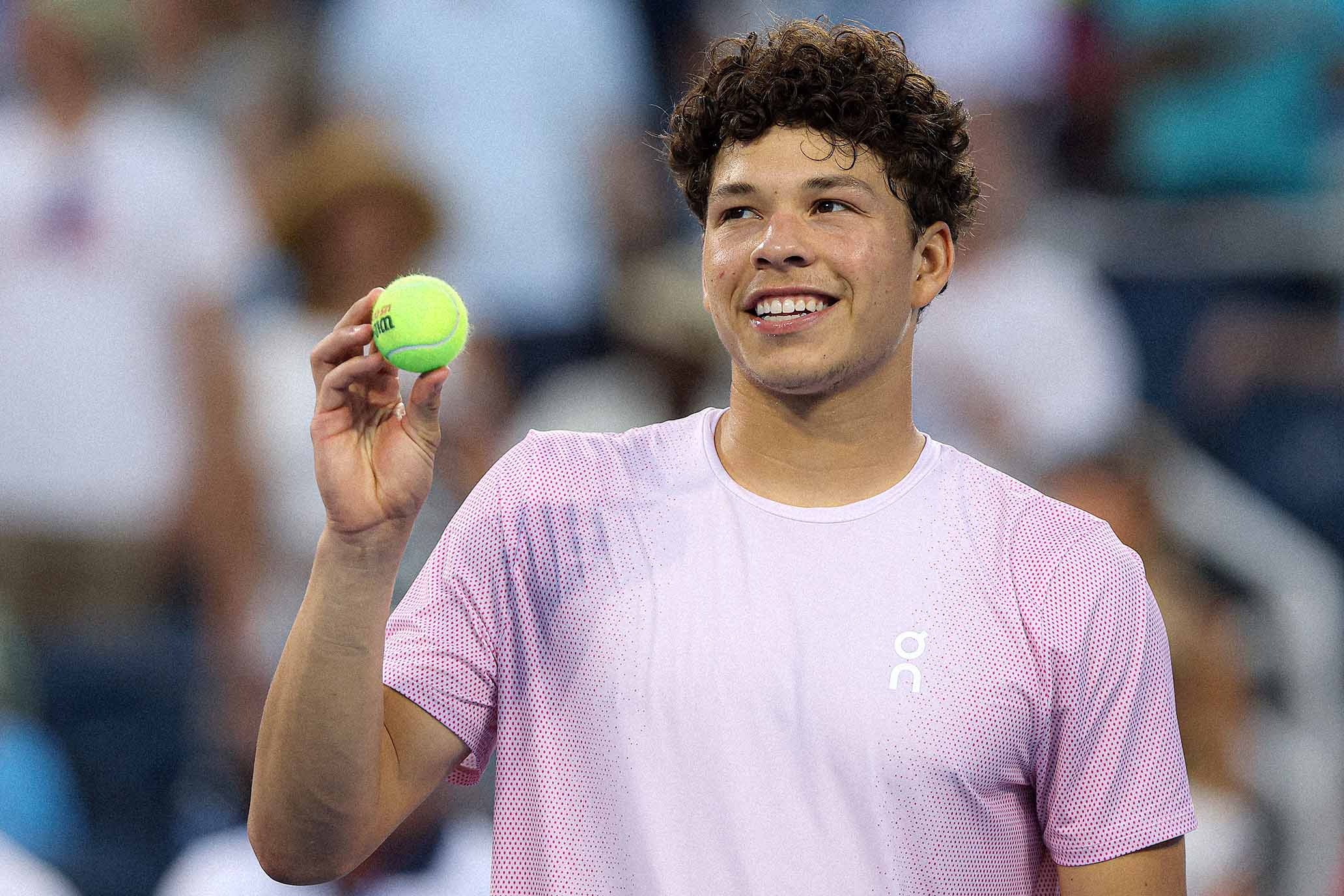

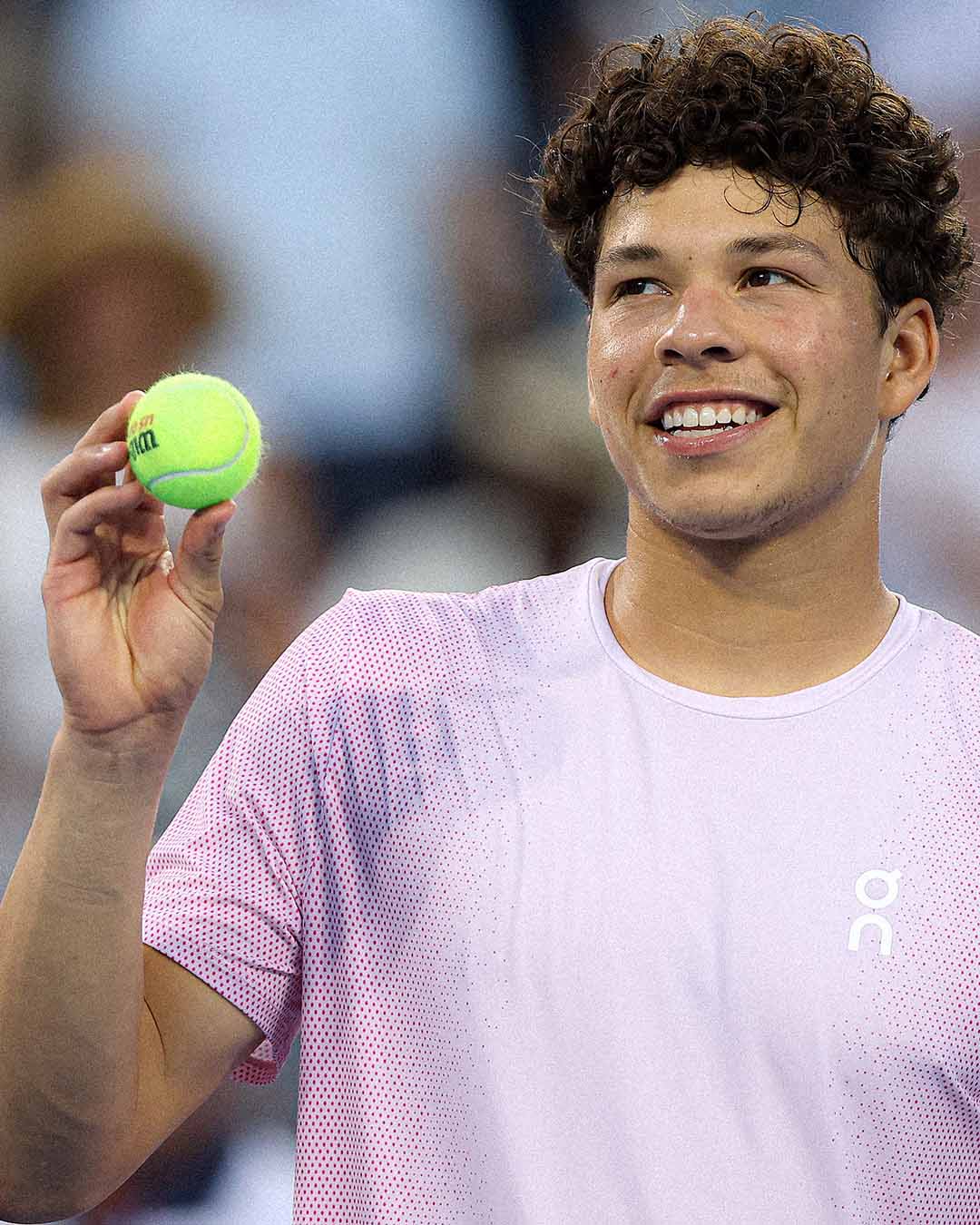

How Good Is Ben Shelton?

How Good, Exactly, Is Ben Shelton?

How Good, Exactly, Is Ben Shelton?

The American sets up shop inside the top 10.

The American sets up shop inside the top 10.

By Giri Nathan

Aug 15, 2025

Ball don't lie. Ben Shelton in Cincy. // Getty

Ball don't lie. Ben Shelton in Cincy. // Getty

How good, exactly, is Ben Shelton? I find myself constantly revising my answer to this question. Which is to his credit.

When he left college to go pro in 2022, I thought he was an outlier athlete with a big lefty serve and a lot of issues in his baseline game. I wasn’t sure how far that could take him. When he immediately made deep runs at the hard-court Slams in 2023, but barely won two matches in a row on the tour level, I became deeply confused. When he won a title on clay in 2024, I wondered if I misread him as a tennis player altogether.

And when, this year, he entered the top 10, I was still having trouble thinking of him as a player of that caliber. At that point in the season—mid-June, grass courts—he had compiled an unimpressive record against top 20 players: just 1–6. That one victory, his best win at that point of the season, was against Lorenzo Musetti, on Lorenzo Musetti’s worst surface, hard court. Was Shelton really a player who would linger in the top 10? What is this numinous idea of a “top 10 player” I have in my head, and how would I need to reevaluate it in this Sincaraz era, where two players so vastly outclass the rest of the field that “top 10” becomes a purely ceremonial descriptor, because they still all seemed irrelevant when it was time to contend for the biggest titles? What was Shelton’s level, really?

Shelton answered some of these questions, forcefully, in Toronto this month. He won his first Masters 1000 title, and in terms of addressing my doubts about his performance against top players, he beat the world No. 17, 8, 4, and 16 along the way. He is closing the gap on Taylor Fritz as the top-ranked American on the ATP. And his tennis looks materially different from how it did when he first landed on tour. Though he seemed at the outset like a servebot, he has proved himself a far deeper player. With that serve he used to go for raw pace; now he’s developed a more eclectic repertoire, always keeping a returner guessing, the way a good pitcher would. From the baseline, he has a much higher rally tolerance. He used to bail out of these exchanges early, going for a premature winner, but he has since shored up his backhand and trusted his beefy legs to grind it out. In fact, despite being a serve-dominant player, he might thrive most on slower surfaces going forward, both because his stamina is a competitive advantage and because he needs the time to set up his ground strokes. Shelton relishes pressure; in Toronto he won three consecutive matches in deciding tiebreaks. And Ben and his dad, Bryan, have established the most persistent player-coach chatter on tour, constantly talking tactics between points. While their dialogue might seem excessive to old-school “solve your own problems” purists, this is the new reality of the tour, and they’re savvy to take advantage of it.

You can already see the fruits of his labor. In the three majors of 2025, Shelton was eliminated by either Jannik Sinner or Carlos Alcaraz, and he kept all of those matches competitive for at least one or two sets, which is more than the rest of the field can boast. There is something to be said for straight-up athleticism and a willingness to mix it up at the net. The serve will always be enough to get his foot in the door. The return game is still very much a work in progress. Of the top 50 players on the ATP, Shelton is currently 47th in percentage of return points won. That must improve. But since he’s sixth in percentage of service points won, he doesn’t need too much of a margin to win most of his matchups. With Sinner and Alcaraz establishing their new regime, it’s an open question who will fill out the upper middle class of the ATP in the years ahead. Daniil Medvedev is in free fall; Novak Djokovic is on his way out; Sascha Zverev has plenty of limitations. Who will it be? Jack Draper needs to stay healthy. Lorenzo Musetti needs to solve hard courts. Jakub Mensik, Arthur Fils, Joao Fonseca, Learner Tien—these all remain quite speculative. Ben Shelton is a good enough player to fill that void, for the moment. Who will follow him? And just how high can he rise?

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Always Moving

Naomi Osaka is Always Moving

Naomi Osaka is Always Moving

As she rounds back into form, the four-time Grand Slam champ is consistently compelling.

As she rounds back into form, the four-time Grand Slam champ is consistently compelling.

By Ben Rothenberg

Aug 8, 2025

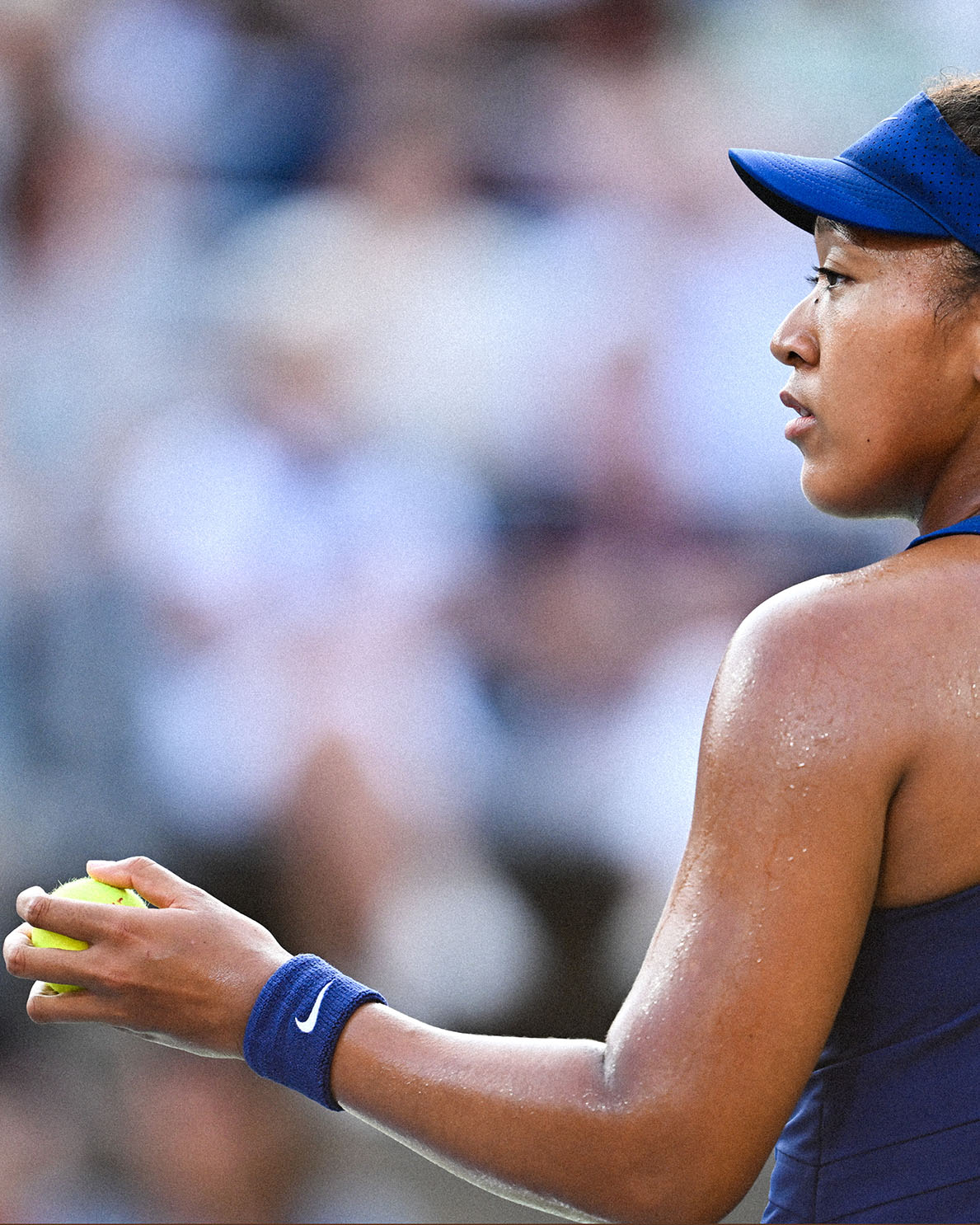

Naomi Osaka is all business during her finals run in Montreal. // Getty

Naomi Osaka is all business during her finals run in Montreal. // Getty

There are three predominant ways folks discussed Naomi Osaka’s resurgent run to the final in Montreal this week. All three of them are technically correct, but all three, I think, miss the real factors at play in her apparent return to competitive relevance.

The first is that Osaka’s great run was thanks to the arrival of Tomasz Wiktorowski, the veteran coach who guided Agnieszka Radwanska and Iga Swiatek through the strongest stretches of both of their careers.

Wiktorowski is a great, proven coach, and he has surely been a positive presence this week in Osaka’s corner. But I don’t think that any coach can change the fortunes of a player within just a few days of meeting her in any meaningful way. Wiktorowski almost certainly represented a positive vibe shift, but it’s tough to know from one week what the long-term returns will be on this partnership.

More than the addition of Wiktorowski, what I think helped Osaka’s equation pay short-term dividends was the subtraction of Patrick Mouratoglou.

Mouratoglou is a smart guy and a savvy businessman with a lot of good ideas about how to grow tennis, but I was never convinced he was a good match for Osaka. His best-known chapter as a coach—helping Serena Williams usher in a second act that put her in the Greatest of All Time conversation—might’ve augured well for his work with Osaka; Osaka also did very well for herself when she previously employed a former Williams coach in Sascha Bajin. But Williams was much closer to peak form when Mouratoglou arrived in 2012 than Osaka was when Mouratoglou came to her late last year, and there’s not a one-size-fits-all fix to reinvigorating the career of another established superstar.

Mouratoglou, too, also didn’t seem to have the focus or hunger for Osaka that he had while proving himself with Williams, spending lots of time and energy and oxygen on his own media pursuits in ways that only served to increase the noise around Naomi. Without any big titles together, the most memorable moment of their partnership might’ve been when Osaka was asked, at a pretournament press conference, what she thought of Mouratoglou’s comments on French television during Roland-Garros that “we’re in a period in women’s tennis where there are no major stars.”

“I didn’t hear that,” Osaka said, betraying some annoyed surprise. “But I don’t know, maybe we should do a powwow about the things that he says. Totally off topic, but sometimes I scroll on Instagram and he pops up and I’m like, ‘Oh wow,’ and then I keep scrolling.”

Osaka has had no trouble generating headlines and attention of her own for the past five years, even without a force multiplier in her corner.

The second misconception is that this week in Montreal was Osaka’s best run since returning from pregnancy and maternity leave. This is true, but I think it’s the wrong framing to use when discussing what Osaka is rebounding from, exactly; she had already slipped far from her peak form well before becoming pregnant in late 2022 and missing the entire 2023 season.

The six matches in a row that Osaka won in Montreal were the longest win streak she’s had since what I think was the peak of her powers: a 23-match win streak that ran from summer 2020 into spring 2021, including her second titles at both the US Open and Australian Open.

In my biography of Osaka, I borrowed a term from Neil Tennant of the Pet Shop Boys to describe Osaka during that time: It was her “imperial phase.” Everything she touched seemed to turn to gold, and she seemed ready to run up the score on court and off; the New York Times Style section wrote a feature called “How Naomi Osaka Became Everyone’s Famous Spokesmodel.”

But right at that apex, Osaka started slipping steeply and then spectacularly, culminating with her withdrawal from the 2021 French Open after a standoff with tournament organizers over mandatory post-match press conferences. Osaka took a few short breaks after that but felt compelled to return to play the Tokyo Olympics—where she lit the cauldron in the Opening Ceremony—and to attempt to defend her title at the US Open.

From the start of 2018 to the 23-match win streak that ended at the 2021 Miami Open, Osaka was 111–36 (75.5%); from then until the beginning of her maternity leave, she was 20–15 (57.1%). Since her maternity leave she’s been 49–30 (62.0%), including the Montreal run that bumped her win rate up by a couple percentage points. I am not sure that whatever derailed Osaka back in 2021—perhaps the various mental health struggles she revealed, perhaps a loss of the hunger that once propelled her, perhaps something else entirely—has yet been adequately addressed.

This leads into the third and most important thing that I think the narratives got wrong about Osaka in Montreal: that, with this run, she is clearly “back.”

Yes, Osaka is likely to be seeded at the US Open later this month, her first time being seeded at a major since her title defense at the 2022 Australian Open. That’s a return to a certain status, to be sure.

But as someone who struggled for more than a year to figure out where her story was headed while writing a mid-career biography of her, the thing I am most confident of about Naomi Osaka is that she remains a moving target, difficult to keep in clear focus with any lens, for any length of time. She’s still growing, still evolving, still learning, still stumbling, still struggling. All humans are doing those things, sure, but with Osaka there’s always been a certain rawness to her visible turmoil that makes it all the more stark, vivid, and captivating.

Her final match in Montreal was, ultimately, a brutal encapsulation of this. Osaka was the much better player at the start of the match, taking the first set 6–2 against the inexperienced Victoria Mboko, a local favorite for the Canadian crowd. But when the match should’ve still seemed firmly in her grasp early in the second set, at 6–2, 1–1, Osaka began to crash out.

First, a crosscourt forehand by Mboko landed near the line; Osaka had expected an out call that didn’t come and grew extremely frustrated extremely quickly, letting the tension of the moment show. When her first serve was called out on the next point, she sarcastically shouted, “I believe you, 100 percent!” toward the chair umpire. When Mboko broke for a 2–1 lead, Osaka dropped her racquet in exasperation, giving both Mboko and the crowd hope that the front-runner might be stumbling.

Indeed she was, and she never got it back together in the second hour of the match, or even after it. Several times she raced through her own service games, wanting to start the next point just a couple seconds after the previous one.

After Mboko won 2–6, 6–4, 6–1, a despondent Osaka left the court and had to be cajoled back on by a WTA handler for the trophy ceremony.

Her eyes still watery, Osaka sounded unimpressed by the Montreal crowd cheering for her for the first time all night as she stood at the microphone. “Thanks, I guess,” she said as she began.

Osaka’s speech lasted only 20 seconds—she conspicuously didn’t mention or congratulate Mboko—and ended with her coldly saying, “I hope you guys had a good night.” Predictably, many of the locals took umbrage at what they saw as a slight to their young new star hero.

Osaka skipped her mandatory post-match press conference, but a couple quotes from her were released hours later, in which she admitted how quickly her own mind can turn on her and acknowledged her slight of Mboko.

“I think it’s kind of funny—this morning I was very grateful,” she said. “I don’t know why my emotions flipped so quickly. But I’m really happy to have played the final. I think Victoria played really well; I completely forgot to congratulate her on the court. Yeah, I mean, she did really amazing.”

Osaka’s second answer accepted the positive framing she was offered about how successful her first week with Wiktorowski had been.

“Yeah, obviously this tournament went really well,” she said. “It could have went better, but that’s just me being picky. I think it was a really good first tournament, and I hope that we can continue.”

Because they are often so compellingly unvarnished, Osaka’s emotional reactions to defeats often gain more attention than her victories. That pattern may well repeat itself after this loss, particularly after runner-up Karen Khachanov was wildly effusive about Ben Shelton in his post-loss remarks hours later in Toronto.

Osaka is aware of this trend and lamented it in a post on Threads hours after her loss at Wimbledon.

“Bro why is it every time I do a press conference after a loss the espns and blogs gotta clip it and put it up,” she wrote. “Wtf, why don’t they clip my press conferences after I win? Like why push the narrative that I’m always sad? Sure I was disappointed a couple hours ago, now I’m motivated to do better. That’s human emotions. The way they clip me I feel like I should be fake happy all the time.”

Osaka is right: she’s definitely not “always sad.” She’s not “always” anything, really. Except, perhaps, continually compelling. No matter her coach, no matter her ranking, no matter if we—or she herself, even—have any idea what she might do next.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

More Than Hype

Vicky Mboko: Way More Than Hype

Vicky Mboko: Way More Than Hype

The Canadian phenom’s title in Montreal has been in the making all year.

The Canadian phenom’s title in Montreal has been in the making all year.

By Carole Bouchard

Aug 8, 2025

Vicky Mboko is all smiles during her title run in Montreal. // Getty

Vicky Mboko is all smiles during her title run in Montreal. // Getty

Victoria Mboko is the tennis tornado the game needs. We all love a prodigy narrative, and there’s nothing like a teenager tearing through draws. And nothing like a teen entering her home tournament, a WTA 1000, with a wild card, and ending up with the trophy after beating another former teen wonder, Naomi Osaka, to clinch the biggest title of a career that has just started.

After Carlos Alcaraz, who’s been defying gravity since winning the US Open at 19 in 2022, and Mirra Andreeva, who’s become a solid top 5 to top 10 player at just 17, the mantle, it seems, has now been passed to Victoria “Vicky” Mboko, an 18-year-old wonder from Canada.

Mboko ended the 2024 season ranked 350th in the world, and now, not even a year later, she is guaranteed a spot in the top 30 (24). “I want to win every match I play,” Mboko told me back in March, and she still sings the same tune in August, saying after dispatching Coco Gauff in the round of 16 in Montreal last week: “When you play a tournament, the goal is to win it.” Tennis, made simple.

As Montreal is rightfully losing its mind over the epic run of the teenager, those who’ve been following Mboko’s season closely saw it coming. On her home soil, the Ontario native, from French-speaking Congolese parents, is displaying why she’s been, outside of the Slams, one of the best stories in the game.

After beating Elena Rybakina to reach her maiden WTA 1000 final, Mboko became the first Canadian to defeat three former Grand Slam champions (Rybakina, Gauff, and Sofia Kenin) in a single WTA event in the Open Era. Osaka made four. And in one single match, she showed why she was turning all heads around this year: She has learned in less than a year how to play and manage matches like a top 10 player. She plays as if she already belongs.

It takes less than a minute for anyone watching Mboko play to stop, gasp, and wow. She possesses a level of effortless power and charisma that draws crowds, along with the risk-taking temperament that comes with it, and an infectious positive energy. She will leave opponents meters away from the ball, whatever their ranking or experience. Her tennis is the definition of bold and unimpressed. She also shows a nice tennis IQ and solid variety in her game. At 18, she walks out there and plays as if she has been playing that way for a decade. Of course, we know it’s easier at that age to swing freely, and that pressure will keep mounting. “We shouldn’t forget that it’s important she keeps smiling out there,” Noelle Van Lottum, who is on Mboko’s coaching team and is also head of women’s tennis at Tennis Canada, told me this year. “What’s most important is that everybody remains calm around her and that we keep helping her improve. Vicky needs to keep that joy to play.” It will be key to keep now more than ever.

Yet her honeymoon phase is fascinating to witness, especially because it’s been percolating for a while. People discovering Mboko through her Montreal run need to understand she’s not a one-week wonder, because Mboko has been improving steadily all year. In the first six ITF events she played in 2025, she won five. When I had my first chat with her back in March, when Mboko was awarded a wild card for Miami’s WTA 1000, her record was 27–1. And she was as bubbly-but-determined about it all as she is now with her 53–9 record.

Mboko is here to win big, that is all. She’s not a longtime Serena Williams fan for nothing. Yet she won’t get ahead of herself, as she already experienced how rough the journey could be when she got sidelined for six months last year due to a knee injury. That’s the thing we don’t want to dwell on, for fear of jinxing her—that Mboko’s main worry moving forward won’t be developing her game but managing her body. After the final, Mboko announced that she will skip Cincy to rehab a wrist injury she picked up during her semifinal against Rybakina, ahead of the US Open. The sport has just one job here: not burning that kid out. “I don’t have so many people around me, and it’s kept me very calm and very comfortable,” she told me this summer. Quiet off the court but enjoying the frenzy of a big court’s crowd is also Mboko’s recipe: She’s been swinging in Montreal in front of a packed crowd entirely devoted to her without being overwhelmed; another sign of a solid foundation. More? You can see she’s enjoying it.

People will say that, with such power and physicality, one tends to move up the ladder quicker. True. But what is also making Mboko’s ascent to the top fascinating, like Andreeva’s, is how quickly she learns. She took over the ITF level in a winter, won her first match in a WTA 1000 in Miami in March, qualified for Rome and won a match before losing to Gauff in three sets in April, then qualified and got to the third round at Roland-Garros, was a match away from qualifying for Wimbledon, then got a lucky loser spot and won her first-round match. And she’s now in her first WTA 1000 final, becoming only the third wild card to achieve this in Canada in the Open Era after Monica Seles (1995) and Simona Halep (2015). She lost against Gauff in Rome and beat her in Canada. She lost against Rybakina in Washington and beat her in Canada. She learns at a speed that will scare a field already busy managing the Andreeva rise. What’s also both scary for her rivals and absolutely amazing for the rest of us is that Mboko is already that good despite having a huge margin of improvement. When they say the sky is the limit, she’s the definition of it.

The last Canadian woman to play in a final at home was Bianca Andreescu, who won there in 2019 and went on to win the US Open. She could be a good example for Mboko, as her rise was also spectacular, but the journey kept getting harder. Mboko, like Andreescu, isn’t a hype; she’s the real deal. It’s no guarantee to become the next Serena, Maria, Iga, Aryna, or Naomi, but it’s a great chance to have a fair shot at it. “To get this result in a tournament like this is a huge turning point for me,” said the teen wonder in Montreal, already aware of how a tennis journey can be slowed or fast-forwarded. In Montreal, it may have skyrocketed.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Genie Bouchard's Long Goodbye

Genie Bouchard’s Long Goodbye

Genie Bouchard’s Long Goodbye

It’s been a wild ride for tennis’ original influencer.

It’s been a wild ride for tennis’ original influencer.

By Giri Nathan

Aug 1, 2025

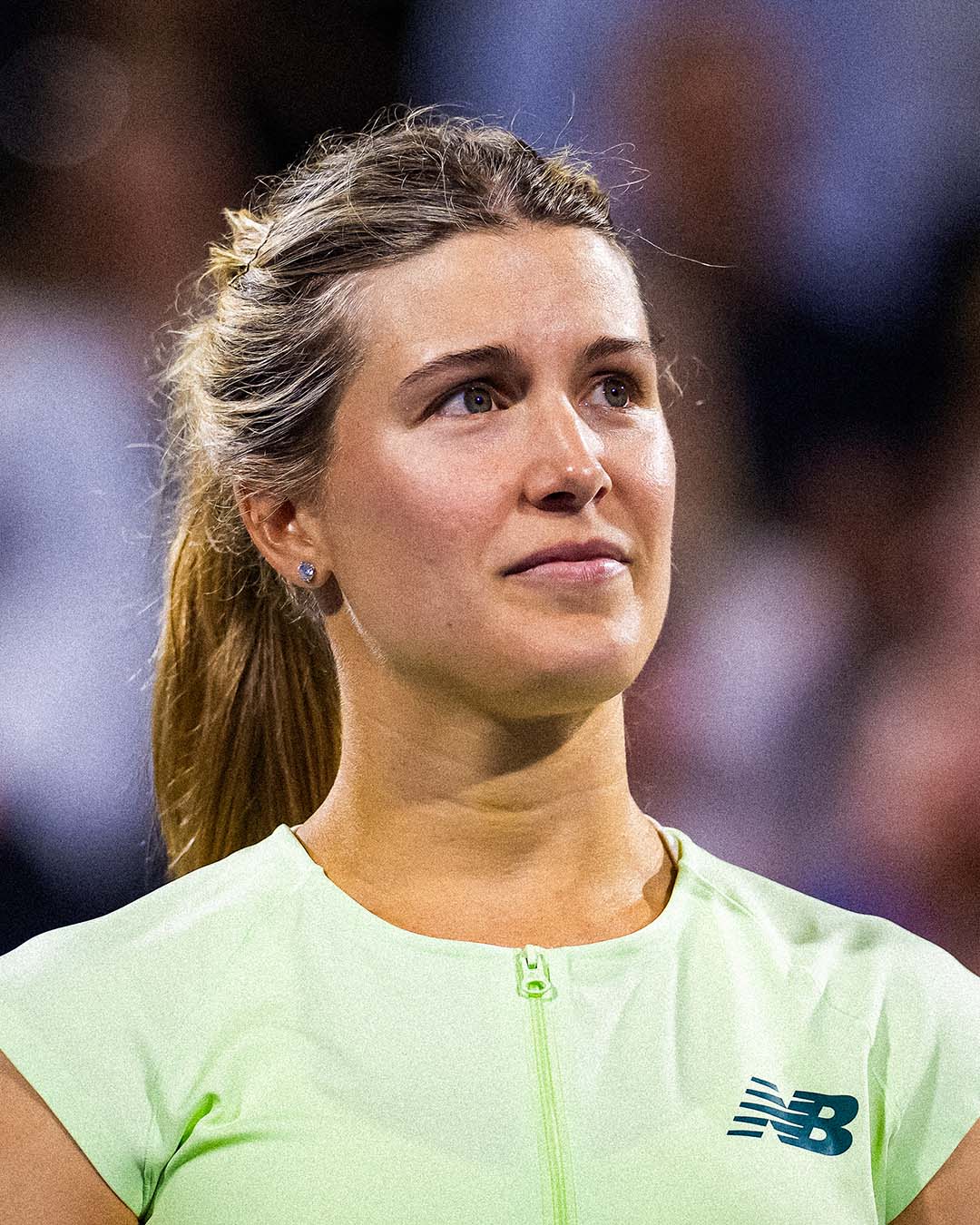

Genie Bouchard says goodbye at the National Bank Open in Montreal. // Getty

Genie Bouchard says goodbye at the National Bank Open in Montreal. // Getty

Tennis success is so fickle. In the 2014 season, Eugenie Bouchard turned 20 years old and shot up the rankings. She had an aggressive style, sitting on the baseline and taking the ball early with compact, almost stilted ground strokes. She was a semifinalist at the Australian Open, semifinalist again at Roland-Garros, runner-up at Wimbledon. By the end of the season, she was No. 5 in the world. Bouchard achieved many firsts for Canadian tennis. After a run like that, she appeared to be on course for a Hall of Fame career.

As we now know, that isn’t how her career played out. In the following 2015 season, her results settled back down to earth. During a strong fourth-round run at that year’s US Open, Bouchard slipped on a tile floor in the locker room and suffered a concussion, an injury that forced her to withdraw from the tournament and, as her lawyers would later argue in U.S. federal court, hampered the rest of her career. (In 2018, Bouchard and the USTA reached an undisclosed settlement.) Sadly, I might have followed this legal saga more closely than her on-court highlights from this point onward, all the way up to her retirement from tennis this week.

If the post-concussion symptoms that followed that fall were as serious as those alleged in the lawsuit, that would indeed be tragic. It is also possible that, for any number of reasons unrelated to that fall, Bouchard just happened to produce her career masterworks before embarking on her 20s, like a Nas or Rimbaud. It was always going to be a challenge to try to replicate the magic of 2014. Sometimes tennis players start out hot, only to get solved by opponents over time. It happens. Here, though, the decline was shockingly abrupt. Bouchard was ranked No. 47 in the world at the end of 2016, then No. 81 in the world at the end of 2017. A few months later she was out of the top 100, where she would remain for almost the whole remainder of her career.

Through it all, Bouchard was still very much…around. In fact, she was making some of the best money of any female athlete in the world, according to Forbes lists published in 2017 and 2018, the same years of her on-court decline. No matter how the tennis matches were going, brands continued to deem her a compelling saleswoman. She modeled. She posted a lot of “lifestyle” images on social media. She did some cheesy stunts, like agreeing to go on a date with a random internet user after a wager on the outcome of the 2017 Super Bowl. When the prize money dried up for Bouchard, she found that she could still monetize attention. Eventually the traditional high-end tennis sponsors stopped renewing the contracts. One day you’re peddling Babolat racquets, the next day you’re peddling an e-book about cryptocurrency.

This is the move that probably soured many tennis fans on Bouchard: becoming a hybrid professional tennis player/influencer. Perhaps the fans felt that a genuine athlete shouldn’t stoop to this stuff. Perhaps she was just too abrasive and frequent with the posts. Perhaps this “secure the bag” mentality wasn’t going to win her much sympathy, given her preexisting reputation and upbringing. (She was born to an investment banker dad, who tried to devise a scheme so her tennis training costs would count as tax-deductible business losses, only to be denied in Canadian court, which ruled that these were actually just personal expenses and a 9-year-old Eugenie did not have the capacity to sign away future earnings.)

Or perhaps Bouchard was just a little ahead of her time. Because that’s pretty much what all the top players do now, without much hate—shill things on Instagram. On-court prize money has always been a fraction of what players can make on ads. As a society we have figured out how to spend even bigger chunks of our days consuming such ads, often dressing them in the guise of things that are not ads. With the memory of her spectacular 2014 season fading, Bouchard was like so many people at this dire moment in culture: trying to take a short bit of fame and spool it out into a longer-lasting revenue stream.

Amid all those extracurricular activities, Bouchard did keep touring, and in spite of injuries and struggles with form, she had an interesting result here and there in her late career. She only let up in 2024, when she accepted the fate of a near-terminal tennis player: pickleball. For a time she played both games professionally. Earlier this year the 31-year-old Bouchard announced that she would be retiring from tennis at her home tournament in Montreal, where she played some excellent matches this week. She won a three-setter against Emiliana Arango, and in the second round she nearly pulled off the upset of world No. 20 Belinda Bencic. As for what’s next? She’s not sure yet. But it’ll probably be hard to miss.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

For Foki's Sake

Alejandro Davidovich Fokina dreams big.

Alejandro Davidovich Fokina dreams big.

Despite finals setbacks, Foki has his sights set on the majors.

Despite finals setbacks, Foki has his sights set on the majors.

By Karina Niebla // CLAY

July 30, 2025

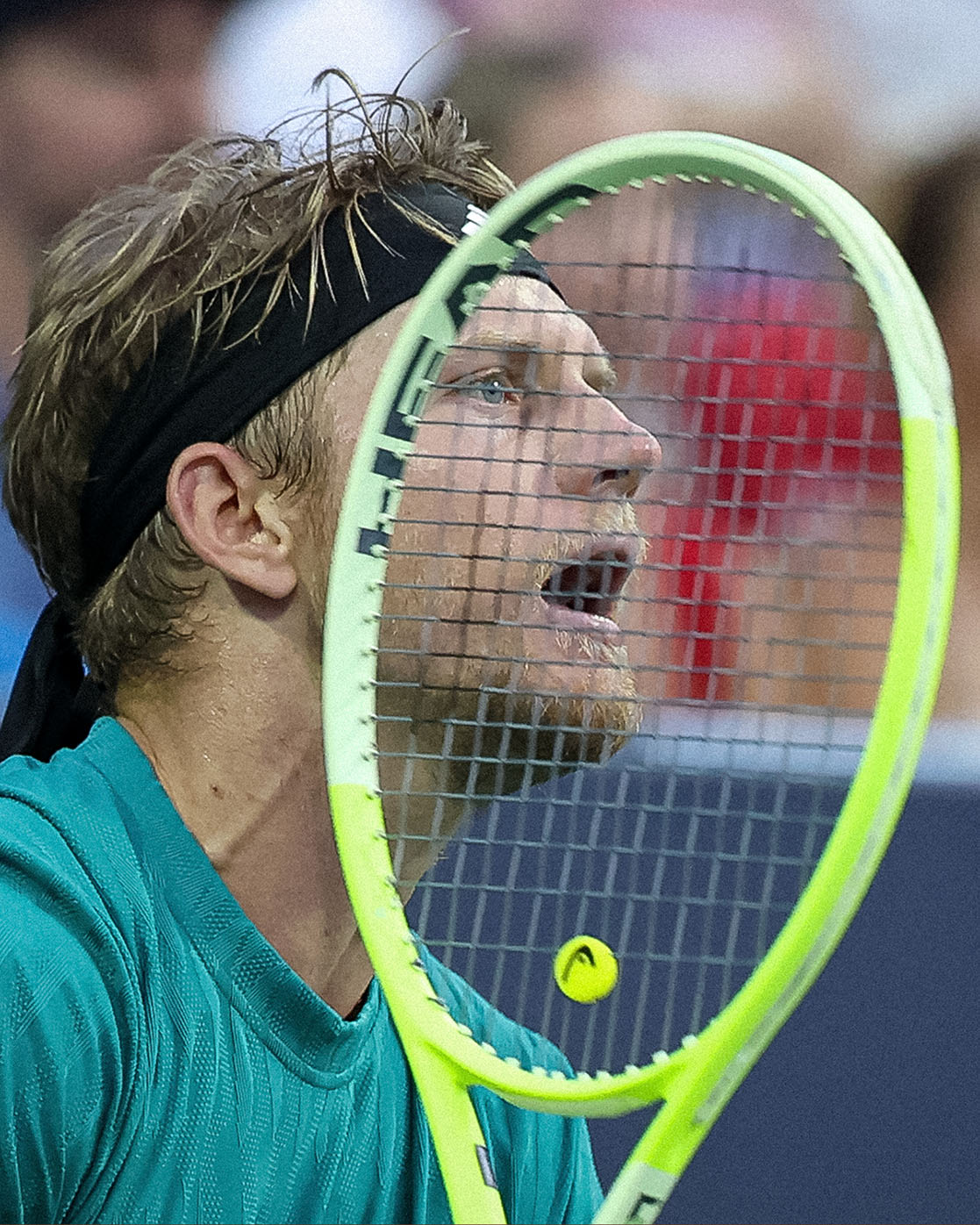

Foki tries to go the final mile in DC. // Getty

Foki tries to go the final mile in DC. // Getty

HAMBURG—Reaching a final, if not actually winning one, is most likely the goal of any pro tennis player. Losing them every time is certainly not, but that’s the recent reality for Spain’s Alejandro Davidovich Fokina: He’s played four finals on the ATP Tour and lost all four, the most recent being his gut-wrenching loss to Alex de Minaur in D.C. on Sunday. And cracking the top 20 for the first time, it seems, was no consolation.

“I’m happy to be in the top 20, but the goal was to win the title,” Davidovich Fokina said after his most recent finals defeat, in which he was up a break in the third set and with match points on his racquet, before ultimately losing the match—a near mirror image of his loss in February in the Delray final against Serbia’s Miomir Kecmanovic. Another final was lost to Tomas Machac in Acapulco in March.

CLAY’s Karina Niebla sat down for a long chat with Foki this year at the Hamburg Open. Known for his sometimes harsh demeanor and sharp tongue—and for being superstitious enough to have been playing in one white and one black sock since he was 15 years old—the Spaniard revealed himself to be a sensitive, at times candid, person, although he describes himself as sometimes having the bearing of “a volcano.”

You’ve been very close to winning a title on several occasions. How do you deal with the mix of hope and pressure that comes with being so close?

This is the year I’ve felt closest to winning that first title. The year is still long, there are many tournaments, and obviously every week I try to go further and beat better players. But above all, I try to enjoy being on court and give my best version.

You’ve had some very important wins this year, like the ones over Taylor Fritz and Andrey Rublev. Was there any change in your game or in how you approach matches that’s helped you take that step forward?

It all started in May last year when I left the coach I’d had my whole life and decided to make a change. I moved from Spain to Monaco, where the top players train, and I rebuilt my team. It’s true that until November someone from the old team was still with me, but it felt like starting from scratch. It wasn’t easy. I was pretty out of it, wanting the season to end because the decision wasn’t easy, but I don’t regret for one second stepping out of that comfort zone and facing those fears.

How did you face them? What kind of mental work did you do?

When I was younger I worked more with a psychologist, but I haven’t done that in a long time. I don’t think it helped me much. It’s more about a shift inside you and what you want to do. In the end, if you decide to do something, it doesn’t matter if 20 people tell you. And if you don’t want to do it, you won’t. The only way to face those fears is to decide for yourself that you don’t need anyone’s help to do it. And that’s what I did.

Speaking up helps too, right? In a post-match interview after failing to close it out—and even serving underarm when you were close to match point—you were very honest and said, “I shit myself.”

After Wimbledon, yes. It was a very tense moment, and I admitted it was a mistake, but that’s how it goes. At other times, I don’t feel that pressure or don’t go for the underarm serve, and nothing happens.

If you could choose any tournament to win your first title, which one would it be?

Roland-Garros.

Do you feel like there is much more pressure at a Grand Slam, like it’s another dimension?

All Grand Slams are very special for everyone, and you have to play best-of-five…. At the end, I’m one of the players with the best percentage in long matches, so it doesn’t feel that tough. Of course, I’d like to win more matches in straight sets, but everyone plays well. There are lots of ups and downs. Matches are long, so it’s normal to lose a set or two. You have to adapt to the situation.

What did you think of Nadal’s very brief farewell in your hometown, Málaga? The tribute in Roland-Garros seems like it’ll make up for that, at least in part.

I thought it was really sad. I think they had a proper farewell planned for later, but since Spain lost in the first round, it turned out like that. When I saw it, I said, “A tennis legend doesn’t deserve a send-off like that.” And not just in tennis, but off the court, too. For me, every tournament in the world should honor him. Roland-Garros is one of them. Nadal is the one who’s won this Slam the most, so it’ll surely be a beautiful moment.

What’s the hardest part of this sport?

Staying at the top. Many players get there, but staying is the hardest thing.

How do you deal with a loss? Do you isolate, do something else, move on quickly?

Now I know how to handle losses well. I know that in tennis, you win and lose every week, and you have to manage that. If you’re well supported, your team understands that. They know you’ll have another shot the following week. It’s about seeing it as a process, learning from your mistakes, and correcting them.

Does the ranking weigh on you? Or do you try not to think about it?

It weighed on me more when I was ranked 70th, at the beginning of the year. I think I’m lucky to be where I am now, and it doesn’t bother me. I want to keep moving forward and enjoy every week. I have to stay humble with every moment and everything that happens around me.

Have you gone through rough patches or moments where you thought it wasn’t worth continuing?

Last year I had a moment like that. If I’d known what was coming, I would’ve signed for that bad end of the year to start the best year of my career. In the end, going out there and losing over and over made me stronger.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

Transit of Venus

Venus Williams Gets Her Benefits On

Venus Williams Gets Her Benefits On

At 45, the legend is back on court.

At 45, the legend is back on court.

By Giri Nathan

July 25, 2025

Venus Williams is all smiles after defeating Peyton Stearns in DC. // Getty

Venus Williams is all smiles after defeating Peyton Stearns in DC. // Getty

The 45-year-old Venus Williams, long absent from the tour, returned to the tennis court in Washington, D.C., this week, thanks to a wild card into the WTA 500 event.

Like so many other wild cards granted to aging legendary players, it seemed like the goal was to delight fans, rather than to invite a player who could realistically advance in the tournament. Williams had spent much of last year recovering from a surgery to remove uterine fibroids, a condition she had been dealing with for decades. She hadn’t played a match since March 2024, and she hadn’t won a match since August 2023. But when she proposed the idea of a comeback to her friend, the billionaire tournament owner Mark Ein, he immediately embraced it.

What should we expect? A pleasant homage to one of the sport’s greats—but not much of a real tennis match. At least, that was the cynic’s outlook heading into Tuesday evening, when Williams wound up becoming the oldest player to win a WTA singles match since Martina Navratilova in 2004. The elder Williams sister had clearly tuned up her game for more than a quick nostalgic hitting session, and she defeated world No. 35 Peyton Stearns, 6–3, 6–4.

In those two sets we saw many of the familiar stamps of Venus’ tennis. The graceful baseline power, courtesy of long levers moving with immaculate timing. Sometimes, watching an older player, you can see clearly that the game has passed them by; they haven’t yet invented ball-striking that can outclass a Williams sister. In her best rallies, the pace and depth coming off of Venus’ racquet were on par with the heaviest hitters of the present. It had been a long time since I saw her distinctive super-early preparation and low take-back on the backhand, running out to the ball with the racquet already stowed away, ready to fire. And since few things in a tennis game age better than a serve, she was in a deadly rhythm throughout the match, breaking the 110 mph mark several times and racking up nine aces.

After she pulled off the upset, Williams offered the crowd a big smile, a twirl, and a concise commentary on American health care. “I had to come back for the insurance, because they informed me earlier this year I’m on COBRA. So I was like, I got to get my benefits on, started training,” she said in her on-court interview. “Let me tell you, I’m always at the doctor, so I need this insurance.” (Sen. Bernie Sanders shared the video on social media to argue that the country needed Medicare for All, if even its millionaires were struggling with the system.)

For all the age-defying thrills of Tuesday’s upset, Williams’ second-round match on Thursday proved that there are at least two things that become way, way harder for an athlete in her fifth decade: recovery and movement. It had been nearly two years since she’d had to play two professional singles matches in the same week. She also played two doubles matches this week, and the fatigue was obvious midway through the first set. Her second-round opponent, world No. 24 Magdalena Frech, had a good enough finesse game to send her slices and short balls that kept Williams scrambling along the court’s vertical axis. Add in the fact that Williams herself couldn’t find the same rhythm on serve, and she wound up with a relatively uneventful 6–2, 6–2 loss.

“Oh, I had so much fun,” Williams said afterward. “Definitely not the result I wanted, but still a learning experience. The part about sport [and] life is that you never stop learning.” She’ll be back on court soon in Cincinnati, where she’s got another wild card, and then again at the US Open, where she will be playing, at the very least, in the star-studded mixed-doubles tournament. While she’s been coy about her precise plans for this comeback, and one might reasonably read “retirement tour” as the subtext, this week has made me even more curious about the tennis she still has left to give.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

The Goat in Winter

The Goat in Winter

The Goat in Winter

How do we think—and feel—about Novak Djokovic now?

How do we think—and feel—about Novak Djokovic now?

By Owen Lewis

Jul 22, 2025

Is it too soon to count the Djoker out? // Getty

Is it too soon to count the Djoker out? // Getty

Twenty years into Novak Djokovic’s career, you’d think evaluating where he stands at any given moment would be easy. I still have no idea how to talk about him.

To be fair, Djokovic is a complicated guy. His best tennis is robotically perfect, but his demeanor as he plays it resembles a tortured, tempestuous mad scientist. He is powered by spite but guided by love. For all his kooky beliefs, he has had a fairly clean bill of health across his career. The vigor of his enduring army of haters is eclipsed only by the devotion of his army of fans. Djokovic’s quirks have enabled controversies, unexpected redemption arcs, and an improbable and unsettling bromance with Nick Kyrgios. Good luck keeping his next biography under 1,000 pages.

The Djokovician puzzle extends even to how he looks. When he plays through various gnarly injuries, he appears to be in agony—but his shots themselves are often unaffected. Even his opponents seem confused and distracted by the dichotomy: How much pain is he in? When he is down a set and a break and looks listless, is he tanking? Is he trying to make his opponent think he’s tanking so he can surprise them by trying his hardest later? Hell, how does that hair remain so thick and still on his head, as if encased in invisible amber? In lieu of Djokovic writing a book detailing the precise sensations he felt in his torso while winning the AO for a ninth time with an ab tear, I would accept merely knowing what type of shampoo he uses.

In 2025, Djokovic is introducing new mysteries directly relevant to how he might wind down his all-time-great career. The year got off to an auspicious start with a titanic four-set win over Carlos Alcaraz at the Australian Open. Djokovic tore his hamstring in the first set and spent the last three defying conventionality in every way possible (i.e., he hit his second serve like a first serve for hours on end without it ever really catching up to him in the form of double faults). Six weeks later, he’d taken the first of four straight sleepy losses. Judging from his demeanor in those matches, he could muster an honest effort for one set, but never two in a row. By the fourth loss in a row, Djokovic’s retirement at or before the end of the season seemed inevitable. He responded by making the semifinals at both Roland-Garros and Wimbledon.

At 38, Djokovic remains a clear cut above everybody not named Carlos Alcaraz or Jannik Sinner. He’s even proved a riddle Alcaraz cannot yet solve, though the matchup is played on more favorable physical terms for the youngster with each passing edition—Djokovic has won four of the last five. It’s the matchup with Sinner, though, that has been Novak’s undoing. Sinner has won their last five matches and their last nine sets. For all Djokovic’s returning prowess in the past, the slower version in the present can’t break Sinner’s serve with any regularity.

In 2024, I wondered if Djokovic viewed Sinner as a bastardized version of himself: someone who was similarly well-balanced on forehand and backhand, hit the ball even harder, and was yet to develop the finer touch and variety that Djokovic spent years perfecting. He seemed less effusive in press about Sinner than Alcaraz, whom he heralded as a completely unique opponent. Watching Djokovic lose five of six sets to Sinner that year without producing a single break point, I thought he had essentially punted on the matchup. Djokovic may have been a more complete player than Sinner, but he needed endurance that he no longer had to grind Sinner down, and it looked like Djokovic knew it. Novak has played Sinner with more vigor this year—particularly in a high-quality Roland-Garros semifinal. But he hasn’t been able to win a single set.

Is it worth it for Djokovic to keep playing, even as the third-best player in the world, if he can’t beat this guy? Should it be? I tend to think no, but if I imagine sitting in a pressroom and putting those questions to him, it feels a little like sacrilege. Part of that is because Djokovic is the best player ever, and implying that he can’t do anything, no matter how difficult, bears a strong risk of backfiring spectacularly. Part of it is his devoted, tribalistic fan base, primed to pounce on anybody who criticizes their man. It’s also hard to tell whether Djokovic has been entirely interested in these matches (he seemed to give all he had in a tight straight-set loss at Roland-Garros, not so much at Wimbledon or the 2024 Australian Open). Despite more data on Djokovic existing than ever, I can’t quite figure him out.

Other publications seem to be struggling as well. ELLE (not exactly a regular tennis read, but still) delivered a terrifying kicker that called Djokovic, a man who refused to take the COVID vaccine and once showed up to an interview with the knowledge he was testing positive for it, “our new favorite wellness guru.” Tennis Abstract, the invaluable tennis analytics site, rated Djokovic’s chances to win Wimbledon about three times higher than eventual champion Sinner’s going in. Prior to the 2024 Wimbledon final, in which Djokovic played Alcaraz, ESPN’s D’arcy Maine wrote in a prediction piece, “Thinking about this logically, it seems as if Alcaraz should win…. [This] is still Novak Djokovic, arguably the greatest to ever play the sport. I just can’t see him letting this opportunity—especially after the bitter disappointment of last year—slip away. Don’t ask me to explain it any further, I’m just going with Djokovic in five sets.” Alcaraz obliterated him—but Djokovic hit back to win the Olympic final weeks later, when barely anyone gave him a chance.

Maybe Djokovic takes pleasure in his slipperiness, in defiance, in not giving observers exactly the answer that they want. Each time someone mentions Djokovic’s unending drive to be the best ever, recall that he skipped multiple tournaments, including majors, rather than get the COVID jab. The spark he needed to beat Alcaraz in Australia was a local anchor making light of his 2022 deportation saga. What I think keeps him playing is less about trying to beat Sinner again than proving his doubters wrong one last time (did you see the smile on Djokovic’s face when Ben Rothenberg told him the oft-memed lady who held up a single finger as Federer had match point on Novak in 2019 now supported him?), it’s just that the two happen to align at the moment. When Djokovic lost to Sinner at Roland-Garros, his wave to the crowd looked unmistakably like a final goodbye; after the heavier loss at Wimbledon, he said he wanted to return to SW19 “at least” one more time. That’s defiance.

I think it’s also worth wondering, though, how admirable that defiance is at this point in his career. With all the records broken and all doubters silenced, what is really left to defy at this point? If anyone ever attempts to use the losing streak to Sinner as evidence for Jannik being the better player, any honest tennis historian will surely mention that Djokovic was clearly in decline in four of the five defeats. He’s safe, and you get the sense that somebody should tell him that. I’m also skeptical of the idea that being ranked third is a pleasure that entirely justifies his prolonged career—he’s been ranked first longer than anyone else in history. If those memories aren’t scratching the itch, he has plenty from his years as the perennial No. 3 during the Federer-Nadal era.

Maybe his drive comes from wanting to win a 25th major, a landmark that is no more meaningful for breaking a tie with Margaret Court than for being a quarter of the value of 100. After all, only one player is a stubborn roadblock for him, and that player could theoretically lose (but can’t you also imagine Sinner making the final of every major until the 2030s?). To me, at least, an athlete as hypercompetitive and accomplished as Djokovic winning a final big trophy by virtue of Sinner losing to somebody else would reveal less about Novak than if he retired right now. And is it really love of the game keeping Djokovic around? He rarely misses an opportunity to let us know he cares almost exclusively about the majors at this point.

His longtime rivals Federer and Nadal pushed their careers too far, and injuries ended them unilaterally. If Djokovic plays on, as I think he will, he risks the same fate. But maybe he can prove me wrong one last time.