The Final Confessional

The Final Confessional

Roscoe Tanner Seeks Redemption.

Roscoe Tanner Seeks Redemption.

By Joel DruckerJune 13 2025

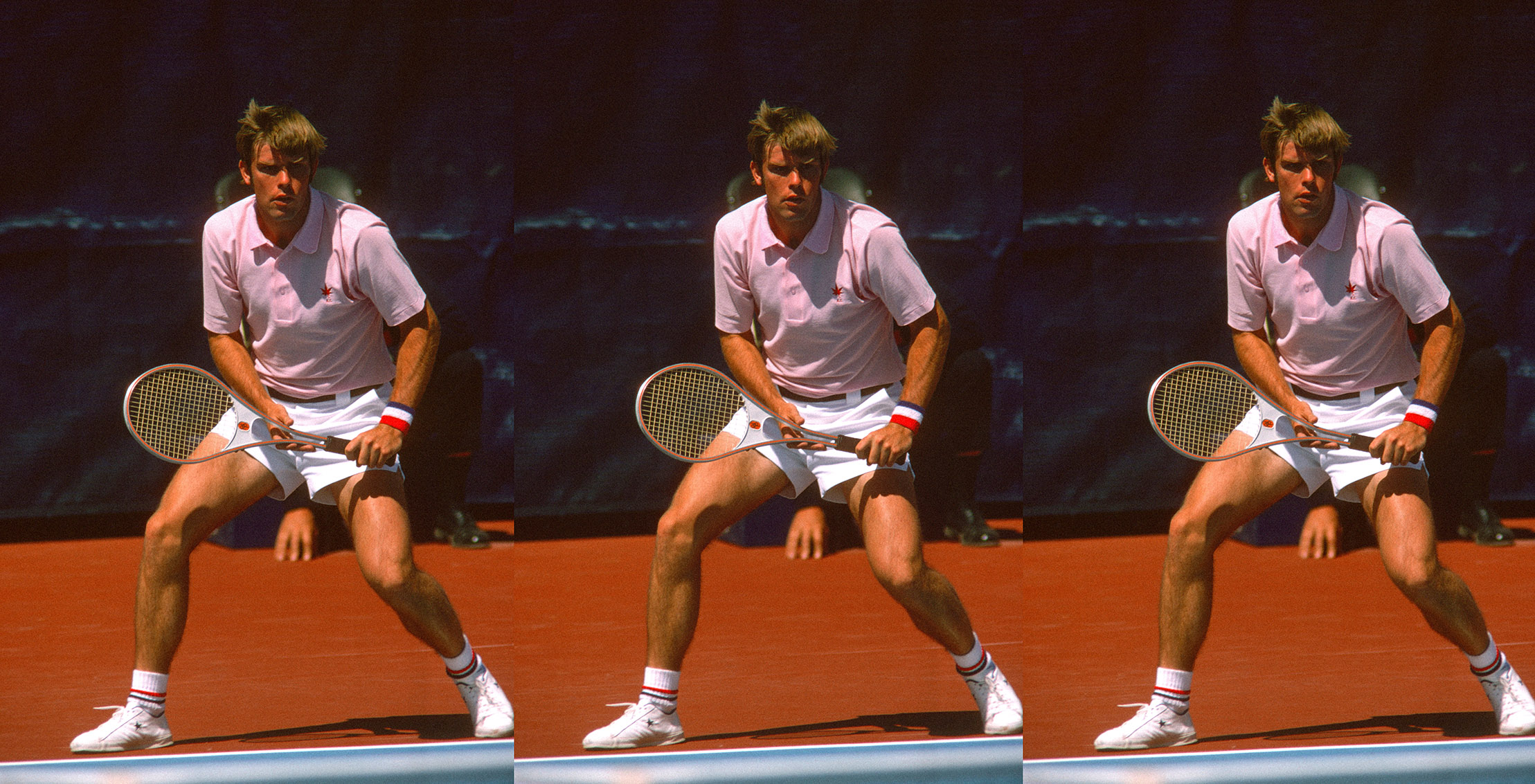

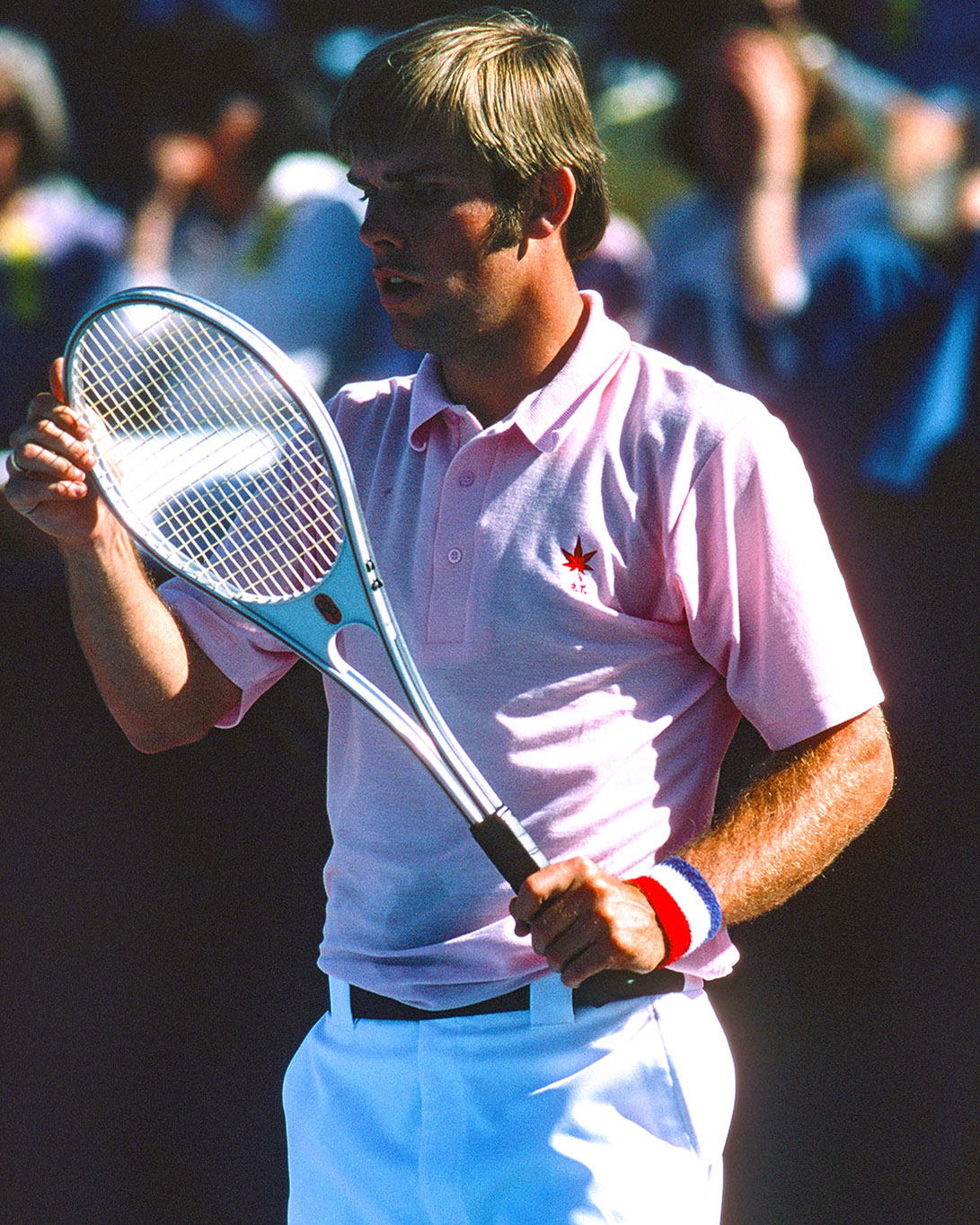

Roscoe Tanner at the American Airlines Tennis Games, Tucson, AZ, 1975.

Roscoe Tanner at the American Airlines Tennis Games, Tucson, AZ, 1975.

Father’s Day promises to be a busy day for Roscoe Tanner. There’s a good chance he’ll go to the church he attends near his home in Orlando. Tanner might also spend time on the tennis courts of several facilities he teaches at roughly 15 hours a week. Perhaps he’ll show a foursome of beginners the fundamentals of doubles. Or help a college player understand the nuances of the serve-volley tactic that took Tanner to a career-high ranking of fourth in the world. And maybe one student will seek to mimic Tanner’s whiplike, left-handed service motion that was once clocked at 153 mph.

But Tanner’s greatest joy on Father’s Day will come from contact with his five daughters—Lauren, Tamara, Anne Monique, Omega, and Lacey. Five women from four mothers, all the children at last on good terms with a man who for decades neglected his spousal and parental responsibilities in ways no one would dare wish upon anyone. From missed child-support payments to bounced checks to multiple jail terms, Tanner has both inflicted pain and paid a heavy price for a series of horrendous choices. He knows this, too, and is now keen to publicly make amends. One step forward: the publication of Tanner’s memoir Second Serve: My Fall From Grace and Road to Reconciliation. “What you’re about to read,” writes Stan Smith in the introduction to Second Serve, “is a brutally honest account of a celebrity athlete who experienced the riches of the world—only to see everything evaporate in his hands.”

“I made some selfish choices,” Tanner told me. “There’s no other way to put it. But I paid for that, and now I’m really lucky that that’s behind me.”

If this sounds familiar, that’s because it is. Twenty years ago, Tanner attempted a similar reinvention. Then, too, there was a book, that one titled Double Fault: My Rise and Fall, and My Road Back. But soon after, Tanner relapsed and was once again arrested. “I don’t want to go through a blow-by-blow description of the last fifteen-plus years of my life,” he writes in Second Serve. “You can do an online search if you’re so inclined.” Estimated to have roughly 30 percent new material, Second Serve addresses Tanner’s desire to live peacefully and ethically. “Some people learn about faith with a nudge, other people get it with a sledgehammer,” said Tanner. “I think I’m closer to the sledgehammer.”

Those who’ve known Tanner for years, some back to childhood days playing in junior tournaments, speak of him mostly with confusion and concern, largely because they have such fond memories of the confident and well-behaved competitor he’d always been. According to former top tenner Brian Gottfried, a Tanner tennis mate since their days as preteens in the early ’60s, “Whenever you played Roscoe, it was always fair and square.”

The world saw the swashbuckling Tanner, too, and never more gloriously than on July 7, 1979, when he entered Centre Court to play the Wimbledon singles final. A heavy underdog versus three-time defending champion Bjorn Borg, Tanner competed brilliantly, jumping off to a two-sets-to-one lead before eventually succumbing, 6–4 in the fifth. It was a first-rate showcase of a man who’d thrown himself into the arena and also emerged triumphant for his effort. As a postscript, Tanner defeated Borg in the quarterfinals of that year’s US Open.

Alas, as graciously as Tanner conducted himself inside the lines, temptation beckoned and captured. “But away from the court,” he writes, “I cheated on [his first wife] Nancy with abandon…. I needed the comfort of a warm embrace. The tour was a lonely place where wolves were looking to devour lambs on the court.” While surely not the first athlete to commit adultery, after his playing career ended, Tanner overextended himself beyond belief, triggering a cascade of financial troubles that in time led to his arrest and imprisonment.

As a player, Tanner could always put setbacks behind him and march forward with his own brand of focus and confidence. “The glass was always overflowing for Roscoe,” said Dick Gould, his coach at Stanford. Tanner, though, recognizes that the laser-like focus that helped him win so many matches wasn’t always so effective elsewhere. “But when you transfer that stubbornness into different things that you think you can get done outside the tennis world,” he said, “it doesn’t necessarily work properly.”

Documenting his time served in a German prison, Tanner writes, “They say that a person can live thirty days without food, three days without water, three minutes without air, but only thirty seconds without hope.” Having bottomed out in prison, Tanner surrendered to a higher power. As he writes, “I leaned over my bed and clasped my hands. ‘Dear Lord,’ I began, ‘I’ve done so many wrongs that I don’t know where to begin. I want you to know that I’m sorry for what my life has become. I repent of my sins and ask you to come into my life now.’”

Tanner writes that, “I’m now in a place where I’m content doing my thing—giving lessons, coaching players, and imparting advice about a game that I’ve loved since I was a little boy.” The same week I read Second Serve, I watched the movie Catch Me if You Can. This is the tale of Frank Abagnale Jr. In his youth, Abagnale forged dozens of checks before being caught by the FBI, imprisoned, and, eventually, hired by the FBI. Who better to detect a forger than a forger?

As I pondered Tanner’s fate, I wondered if, akin to Abagnale, he might find meaning as a source of counsel for youngsters about to embark on the pro tennis journey, active pros faced with many hedonistic options, ex-players uncertain of the next best step. For the sport is filled with dozens of these solitary souls who create pain not just for themselves, but sometimes also for others. And while forgiveness can be granted with words, trust is rebuilt best by deeds.

A common trope is to compare tennis to democracy: a fair form of competition, all outcomes based strictly on the ability of an individual to effectively perform. But there is also a downside to such a singular community. In the 1830s, a Frenchman diplomat named Alexis de Tocqueville came to America. Ironically enough given the case of Tanner, Tocqueville’s nominal mission was to study the American prison system. But his bigger quest—less than 50 years after his homeland’s own revolution—was to understand how democracy played out in this former British colony.

Though tennis as we know it had yet to be invented, Tocqueville anticipated what Tanner must have felt during those many solitary days and nights he spent competing all over the world and then returning to his hotel room. Writing in his iconic book Democracy in America, Tocqueville noted that, “Thus not only does democracy make every man forget his ancestors, but it hides his descendants and separates his contemporaries from him; it throws him back forever upon himself alone and threatens in the end to confine him entirely within the solitude of his own heart.”

“I’ve made some mistakes,” said Tanner. “I paid for it, but let’s all learn from it and go forward.” Now 73 years old, Tanner continues his quest to liberate himself from solitude and cultivate love with the many hearts he shattered and is working earnestly to mend. “I missed a lot of time with them,” Tanner said about his daughters. “On the other hand, I prefer to think about where I am right now, and I’m in a good position with each of them.” On this Father’s Day, light a candle and hope that Roscoe Tanner has indeed authored his final confessional.