15.

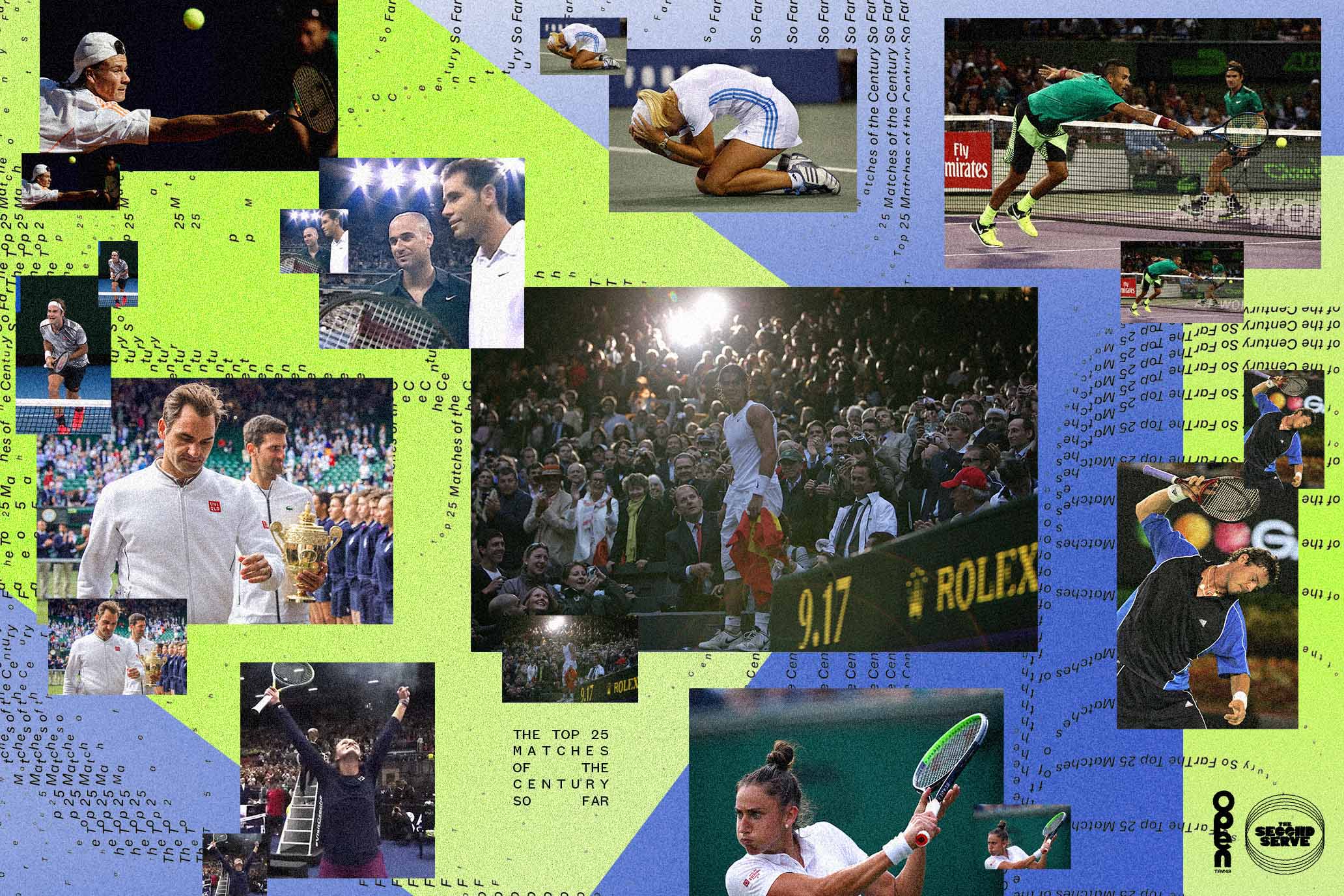

2021 Wimbledon, 2nd Round, Kerber d. Sorribes Tormo, 7–5, 5–7, 6–4

Angelique Kerber’s the queen of angles and timing, Sara Sorribes Tormo is all topspin and stamina, but they share a rare ability to generate classic matches. Their lack of innate power forces them to win points through colorful, inventive means that rub off on opponents and produce ecstatic slogs. It’s a shame they’ve only played each other this one time, and a tragedy that the only public video record of it is Wimbledon’s pathetic three-minute offering on YouTube.

Good thing I could never forget watching it on TV at the time. I’ve never seen a match with so many wonderful rallies—in three long sets on grass, still bright and fast in the first week, these two mustered only 19 combined unreturned serves. Rallies began on even terms and were free to flow to places that most modern tennis matches are too power-dominated to ever visit. This style can produce slower and more masochistic rallies than some are used to, but I think it captures the best of tennis. Such rallies showcase the broadest possible variety of shots on offense and defense, allowing the sport to shine both athletically and aesthetically, and for more than a moment at a time. SST broke serve early in the third set with a lob she hit while running backwards, at the end of an exchange that had already featured a baseline rally, an overhead, and a volley. I’ll take that over serve-plus-one, please and thank you. The match’s conclusion felt inevitable, as in so many Sorribes Tormo marathons: Her nonexistent serve eventually results in a love break at the worst possible time. Even in defeat, her persistence against a better player made her primarily responsible for the best match of the tournament, and the year. —Owen Lewis

14.

2008 Wimbledon Final, Nadal d. Federer, 6–4, 6–4, 6–7, 6–7, 9–7

The ultimate clash of styles, on the biggest stage, for the greatest prize of them all. Federer was trying to win for a record sixth straight time, while Nadal, the clay-court king, was the upstart looking to cause a big shock and prove that he could play on grass.

The anticipation was off the charts; Federer was unbeatable in his “back garden,” but Nadal had made the final in each of the two previous years, and if the fans didn’t know he was ready, Federer did, having been crushed by the Spaniard just a few weeks beforehand in the French Open final.

The match started late because of rain, and when it did begin, Federer was nervous. Nadal took the first two sets and was the better player early in the third, only for an 80-minute rain delay to turn the momentum in Federer’s favor. After grabbing the third set on the tiebreak, Federer saved two match points in the fourth, one with a brilliant backhand pass down the line, to take it to a decider.

The fifth set was again interrupted by rain, and when they resumed, the light was fading fast and it was almost impossible to see, with only TV making it look playable. Federer had the momentum and was serving first, but Nadal was unstoppable, finally breaking serve in the 15th game before serving it out for the biggest title of his life. Federer looked like a broken man. —Simon Cambers

13.

2005 Italian Open Final, Nadal d. Coria 1, 6–4, 3–6, 6–3, 4–6, 7–6

Nadal looked cooked. After three sets of clay-court trench warfare with a far more seasoned opponent, Rafa faltered, losing the fourth and falling down a double break in the decider. The break-back point he held at 0–3 felt like a small diversion before Guillermo Coria’s inevitable victory. Nadal, 18 years old at the time, disagreed: He played a patient, mature rally befitting of a much older player, ending with a perfectly timed forehand drop shot. (Show that point to anybody who thinks Alcaraz was the first Spaniard to use the dropper.) He then raised a thickly muscled left arm, leaped in the air, and roared.

What was powering this kid? Suddenly he had renewed energy, covering the court just as relentlessly as he had early on. If Carlos Alcaraz decided to play like Lorenzo Musetti, you’d get something like young Nadal here. Coria seemed to age trying to get the ball past this misplaced track star, even as he played brilliant tennis of his own. One desperate Coria get, off a screaming Nadal forehand down the line, turned into a perfect drop shot. They collided in a tiebreak, where, in classic Rafa fashion, Nadal finished the match the hard way. After missing a second-serve return on one championship point and double-faulting away another, Rafa chased down a variety of Coria rockets, including an overhead, eventually forcing an error with a vicious forehand pass. Nadal then fell to the ground in ecstasy, reacquainting Coria, best known these days for blowing a humongous lead in the 2004 Roland-Garros final, with how it feels to lose after expending every effort your body could offer up. Coria lost in the first round of the tournament in 2006. Nadal reached the final, played a similar epic against Roger Federer, and won that, too. —Owen Lewis

12.

2003 US Open Semifinal, Henin d. Capriati, 4–6, 7–5, 7–6

The ’03 US Open had been halted frequently by rain, to the point where this intriguing semi between Justine Henin and Jennifer Capriati commenced past 9 p.m.

In June, at Roland-Garros, Henin had won her first major singles title. Following 10 years as a teen prodigy and burnout case, Capriati in 2001 and 2002 had snapped up three Grand Slam singles titles. Each now hoped to reach the US Open final for the first time.

Added to the mix was a pleasing style contrast between Capriati’s forceful ground strokes and Henin’s rainbowlike palette of speeds, spins, and an extraordinary one-handed backhand.

For three hours and three minutes, these two lit up Ashe Stadium. Channeling the energy of the American crowd, Capriati came two points away from winning the match a staggering 11 times and served for it in each of the last two sets. But Henin was that rare mix of artist and warrior, repeatedly able to transition from defense to offense—and eventually, at 12:27 a.m. Saturday morning, she won in a third-set tiebreaker. Later that same Saturday, she would defeat compatriot Kim Clijsters in the finals. Four years later, she’d win a second US Open title.

This loss marked the second time Capriati had been beaten in the semis of the US Open in a third-set tiebreaker. Twelve years earlier, she’d lost that way vs. Monica Seles. And one year following the Henin match, more heartbreak in the semis, Capriati beaten in a third-set tiebreaker by Elena Dementieva. —Joel Drucker

11.

2022 Ostrava AGEL Open, Krejcikova d. Swiatek, 5–7, 7–6, 6–3

The 2022 final in Ostrava was three hours and 16 minutes of women’s tennis played at the height of its modern form. That’s what it took for Barbora Krejcikova to hand world No. 1 Iga Swiatek her first loss in a final in more than three years.

At her best, Krejcikova’s flat pace and depth were the perfect foil for Swiatek’s topspin-driven game. On paper, this had all the markings of an intriguing clash. But great matches are not solely defined by quality of play, dramatics, or significance. The truly memorable ones have a certain X factor, some magical alchemy that makes you feel you’re catching lightning in a bottle. In Ostrava, that X factor was…well…Ostrava!!! (Exclamation points courtesy of the tournament’s own campy branding.) A match between Poland’s brightest young sporting star and the Czech Republic’s newest major champion, played on the border of the two neighboring nations, meant a packed-out atmosphere that felt more like a Davis Cup final than a WTA 500 in autumn.

Swiatek and Krejcikova proceeded to reward the passionate fans with an absolute clinic, with Swiatek hitting 42 winners to 30 unforced errors and Krejcikova responding with 44 winners and 41 unforced errors. After holding off Krejcikova in a 73-minute first set, the Pole was two points from a straight-set win. But Krejcikova kept her cool to edge the tiebreak and broke Swiatek to earn a chance to serve out the win. The match ended in a rousing finale, with Swiatek dramatically saving five match points before Krejcikova fired an ace to win. —Courtney Nguyen

10.

2005 Australian Open Semifinal, Safin d. Federer, 5–7, 6–4, 5–7, 7–6, 9–7

Marat Safin is on the very short list of players who have upstaged Roger Federer’s genius. This masterpiece of a semifinal at the Australian Open 2005 against Federer, the revenge of the 2004 final, is his legacy, ahead of his US Open final perfection against Pete Sampras. On that day, Safin, the temperamental artist who reached world No. 1 at 20 in 2000, the youngest of the Open Era at the time, reached a state of grace.

This semifinal against Federer had it all: out-of-this-world quality and variety of play, cast, stakes, twists, and turns. You couldn’t look away. So here I was, waking up the building in the middle of the night in Paris while yelling, “You’ve got to be fucking kidding me!” when Safin saved that match point in that tiebreak (5–6) and sealed his legend. Federer had hit a superb drop-shot volley, but Marat answered with a perfect lob. On a 26-win streak, Federer had seen and lost his last chance. It would be his only loss on a hard court that year (50–1).

That match has also entered legend, because it glued us until the last shot. Safin had two match points on serve at 5–3 in the fifth, another at 5–4, and two more at 6–7. I was laughing-crying when Federer saved No. 6 at 7–8, as it felt unreal. But then, on No. 7, Safin went for that infamous backhand down the line, saw Federer fall while chasing it down, and let his forehand paint the last stroke. Coached by Roger’s former coach Peter Lundgren, Safin would win the title against Lleyton Hewitt, but he’d never play another Grand Slam final. He had already entered tennis immortality, so be it. —Carole Bouchard

9.

2017 Australian Open Final, Federer d. Nadal, 6–4, 3–6, 6–1, 3–6, 6–3

Imagine possessing 17 Grand Slam singles titles and realizing you must have the courage to implement a significant change. Add the fact that your greatest rival held a 23–11 lead in your matches, including the three previous times you’d played each other on the court you’re about to compete on. This was what Roger Federer faced as he entered Rod Laver Arena to play the 2017 Australian Open final vs. Rafael Nadal. Eight years earlier, a five-set loss to Nadal in the finals had brought Federer to tears. There’d also been semifinal defeats Down Under in ’12 and ’14.

In 2017, Federer arrived in Melbourne ranked 17, largely the result of missing the last six months of 2016 while recovering from knee surgery. He’d also gone more than four years without winning a major. Nadal, also hindered throughout ’16, was ranked nine. Versus Nadal, the Federer backhand had frequently been exposed, primarily due to the Spaniard’s lethal left-handed crosscourt forehand. But on this evening, Federer committed to hitting his backhand earlier and harder. That step would prove decisive, kick-starting Federer’s entire game. Still, Nadal went ahead 3–1 in the fifth—at which point Federer played five of the greatest games of his career. Not just the backhand, but every other aspect of the Federer game sparkled as he earned a redemptive Slam triumph. Federer would go on to win Wimbledon that year and take another Australian title in ’18—his final major. Nadal too would continue to excel, winning another eight Slams. —Joel Drucker

8.

2019 Wimbledon Final, Djokovic d. Federer, 7–6, 1–6, 7–6, 4–6, 13–12

“Tennis is the most beautiful sport there is and also the most demanding,” wrote David Foster Wallace in String Theory, and this match is a stained-glass mirror reflecting the brightest and harshest rays of that truth. I came into this match as a Roger Federer fan, and so did most of Centre Court that day. Federer had just become the first player ever to reach 350 Grand Slam match wins en route to the final, and the world felt primed for another chapter in his glimmering storybook. Which only adds another layer to make what Novak Djokovic did that afternoon feel more impossible. With the stakes as high as ever and the crowd against you, it became the ultimate test of Billie Jean King’s idea that pressure is a privilege. I spent the longest final in Wimbledon history, all four hours and 57 minutes, on Do Not Disturb and clinging to the edge of my seat.

Federer served at 8–7 in the fifth, up 40–15, two championship points from what would have been his ninth Wimbledon and 21st Slam. I vividly remember thinking, This is it, as the camera cut to his wife, Mirka, unable to look, and the commentator saying, “Breathe in, breathe out,” while I tried doing the same on my couch. Then seven straight points from Djokovic. Seven! The crowd roar and buzz turned into deafening disbelief.

This was also the first year Wimbledon used a 12–12 final-set tiebreak, making this the first Slam final ever decided by it. Djokovic, the top seed, defended his title, winning 7–6, 1–6, 7–6, 4–6, 13–12 for his fifth Wimbledon and 16th major, widening their head-to-head rivalry to 26–22. He became the first man in 71 years to win Wimbledon after erasing match points in the final. Federer left without No. 21, without a ninth Wimbledon, and in what would be his last Grand Slam final appearance. After the match, I thought back to Wallace’s words. How can this not be the most beautiful sport there is? —Jordaan Ashley

7.

2017 Miami Semifinal, Federer d. Kyrgios, 7–6, 6–7, 7–6

If there’s been a better three-set men’s match in the past 25 years, I missed it. It wasn’t exactly a shock that these two would put on a show that year in Miami. At 35, and having spent much of 2016 recovering from a meniscus tear, Federer had already startled tennis with a 2017 return that instantly signaled a late-career revival, winning the Australian Open and Indian Wells. (It would turn out to be his best year since 2007!) Nick Kyrgios, for his part, had begun his season beating Novak Djokovic twice: At 21, was he becoming the player he had the gifts to be?

The scoreline alone announces a crazy-good match. A match that, really, came down to three gambler’s go-for-it second serves from Kyrgios, resulting in three crushing misses: one to surrender a first-set break he’d earned; a second in the first-set tiebreak at 9–9 that provided Federer with a set-point opportunity he capitalized on; the third at 5–5 in a third-set tiebreak that he’d lose on the very next point, smashing his racquet after failing to return a Fed serve out wide to his backhand. It wasn’t just how close it was, though. It was everything, or everything you might expect from two players with electrifying attack games: penetrating flat forehands (one from Kyrgios clocked at 119 mph); big serves to all parts of the box; balls taken as early as possible; why-not net rushes, nasty slices, uncanny backhands down the line. And clean, given the point-in, point-out audacity—and the noise from a Key Biscayne crowd that reached Davis Cup decibels. It was proto-Sincaraz, and it was mesmerizing. —Gerald Marzorati

6.

2001 US Open Quarterfinal, Sampras d. Agassi, 6–7, 7–6, 7–6, 7–6

Andre was 31, Pete was 30. The two best players of the ’90s, now in their twilight. Going into the match, Andre had won their last three meetings, 6–1 in the 5th in the 2000 Aussie semi, and then Andre bludgeoned him in the finals of Indian Wells and Los Angeles (yes, there was once a tournament in L.A.). “The feeling that you had walking onto a court with him, you felt like you were a part of something that was bigger than both of us,” Andre told me of Pete back in 2006. “The feeling was its own entity, its own animal, its own energy.”

In their round of 16 matches, Andre had battered an outmatched teenager who had beaten Pete at Wimbledon earlier that summer—Roger Federer—and Pete had beaten the defending champion, Pat Rafter, in four sets.

Andre looked clean in head-to-toe black, ditto for Pete in white. Pete was on fire from the beginning, dialed in, hitting his spots with that perfect serve, demonstrating his uncanny athleticism, point after point, game after game. Andre in free flow was a beautiful thing to see. He could not have played better. Murdering the ball, penetrating the court to Pete’s backhand, over and over. But Pete was knifing the backhand with great success and then ripping it with a remarkable ferociousness that for Andre was hard to forget. When Pete established that he could hang with Andre a little from the baseline, that meant trouble. Neither player lost his serve, but after losing the first-set breaker 10–8, Pete won the next three breakers.

To watch it now is amazing. Tennis is no longer played like that. The evolution of hyper-carbonated ground strokes coupled with the slowing of the courts no longer allows for Pete’s style. A year later Pete would beat Andre to win the Open, 6–4 in the fourth. It would be the last pro match Pete ever played. —Craig Shapiro