Steps Through Timewith Stan Smith

Steps Through Time With Stan Smith

Some people think he's a shoe.

Some people think he's a shoe.

JOEL DRUCKERMay 10, 2024

Some people think he's a shoe.

Steps Through Time With Stan Smith

Some people think he's a shoe.

Some people think he's a shoe.

JOEL DRUCKERMay 10, 2024

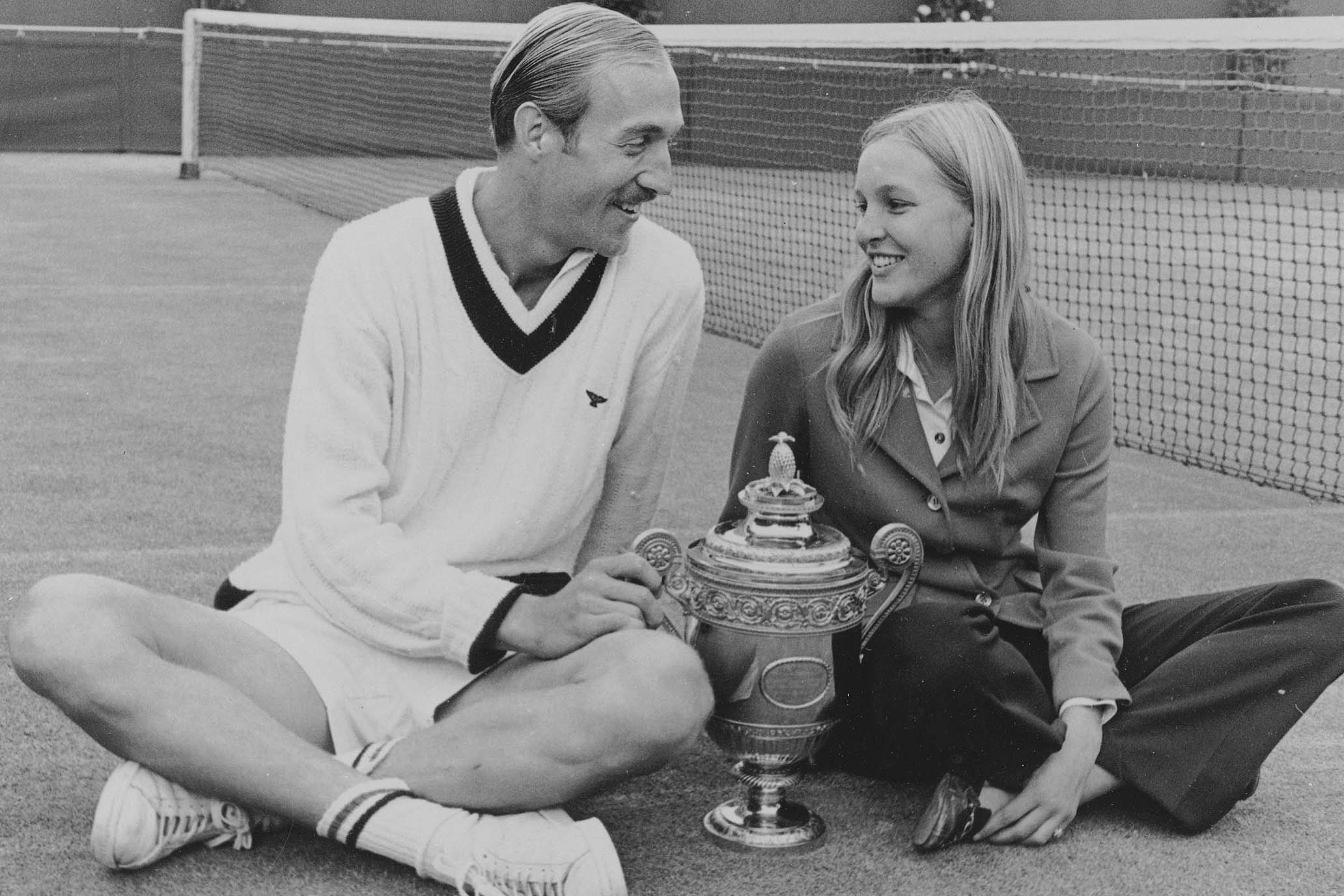

Wimbledon, 1972: "Stan Smith of Pasadena sits with his friend Margie Gengler of Long Island, N.Y, with the winner's cup between them.…" // AP Images

Wimbledon, 1972: "Stan Smith of Pasadena sits with his friend Margie Gengler of Long Island, N.Y, with the winner's cup between them.…" // AP Images

The Nuart, venue for the Los Angeles premiere of director Danny Lee’s documentary Who Is Stan Smith?, is a 95-year-old movie theater that has long hosted independent art films. Located in West Los Angeles, three miles southwest of the UCLA campus, the Nuart is renowned for its midnight showings of the 1975 cult film The Rocky Horror Picture Show, a campy musical whose many songs include “Let’s Do the Time Warp Again.” Fitting indeed that watching this majestic, intimate, and compelling film about a tennis legend put me through a time warp all my own.

It had been more than 40 years since I’d entered the Nuart. But back in my ’70s adolescence, when I’d typically attend a movie a week, I went to the Nuart frequently. For the Nuart was within walking distance of where I lived. It was also right near Stoner Park, the spot where, in 1971, at the age of 11, I’d first hit a tennis ball and eventually play many tournament and high school matches.

My start in tennis happened to take place during Smith’s peak years, roughly from 1971 to ’73. This was when he won the US Open and Wimbledon, led the U.S. Davis Cup team to victory, became No. 1 in the world, helped start the ATP, and soon enough took a political stand. In 1973, as part of their struggle for freedom, Smith joined forces with his ATP brethren to boycott Wimbledon, in the process declining to defend his title.

The film deftly covers all of these occurrences, a nicely paced mix of action, memories, photos, news clips, and thoughts from such experts as John McEnroe, journalists Craig Shapiro and Cari Champion, and Tennis Channel CEO Ken Solomon. Others chiming in include Smith’s onetime Davis Cup captain and agent Donald Dell; doubles partner Bob Lutz; close friends Jeanne Ashe, Charlie Pasarell, and Mark Mathabane; and, of course, Smith’s children and wife of nearly 50 years, Margie. The Smiths’ enchanting marriage conjures up another Nuart-worthy movie, It’s a Wonderful Life. One can easily picture the young Margie whispering into her beloved’s ear, “Stan Smith, I’ll love you till the day I die.”

One pivotal moment for Smith came in 1972, when he and Dell took a midnight meeting with adidas CEO Horst Dassler at a Paris nightclub. Soon after, adidas launched the sneaker that bears Smith’s name and has made him an icon to millions who wouldn’t know a volley from a valley and may have even believed the name “Stan Smith” was conjured up in a Madison Avenue conference room. As Smith titled his 2018 coffee-table book, Some People Think I’m a Shoe.

For someone like myself, who dove into the sport during those boom years of the ’70s, the success of a shoe with Smith’s name on it was baffling. My shoe preference then was for adidas’ blue-striped, meshed Ilie Nastase. Nastase, Smith’s victim in the ’72 Wimbledon final, fit in with Jimmy Connors and John McEnroe as part of a rebellious troika that radically changed perceptions of tennis. If the white-clad, well-mannered Smith was the last of the understated crooners à la Bing Crosby, then these three were the first of the rock stars, taking the game from black and white to Technicolor.

In a decade strongly defined by antiheroes, Smith was Captain America. But perhaps Smith’s constancy was what triggered his shoe’s popularity. “Superheroes don’t change,” said Lee. “They change the world around them.” Tennis’ rock stars have sparkled and strobed, subject to shifts in taste. Smith’s white leather shoe is classic and enduring, a transparent, open-ended licensing agreement of sorts that others could project their designs on.

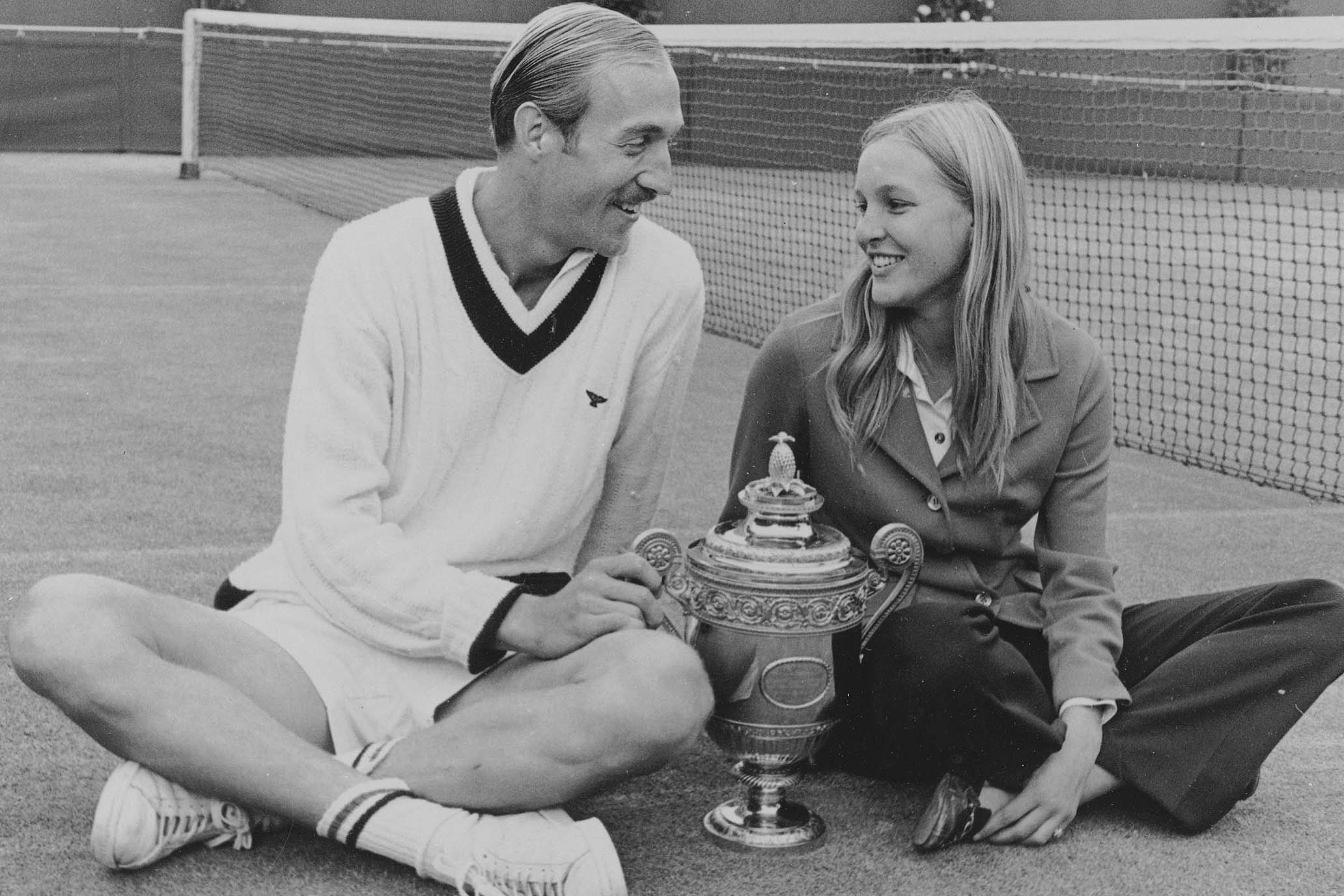

Stan and director Danny Lee at the Los Angeles premiere. // David Bartholow

Stan and director Danny Lee at the Los Angeles premiere. // David Bartholow

As Lee’s film shows, Smith too is transparent, graced with an inner peace that commenced with his middle-class upbringing in Pasadena, a wholesome L.A. suburb. Like all of us, Smith’s life grew into a series of expanding circles and friendships, many of which were deeply formed by the time he was 21 years old. Two factors contributed to the forging of the Stan Smith community at what for many of us is merely a preliminary stage: the extensive commitment required to become a world-class athlete and the volatile times when he came of age.

Smith turned 21 on Dec. 14, 1967. Then came 1968, an exceptionally volatile year, marked by twists in the controversial Vietnam War, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, riots in the streets, and so many other forms of political and cultural tumult that Arthur Ashe later said, “You didn’t get five minutes to breathe.” Even tennis and politics came closer than usual to each other. Donald Dell, the newly appointed Davis Cup captain, was a close friend of the Kennedys, juggling his tennis responsibilities with work on RFK’s presidential campaign. Thanks to Dell, Smith, Ashe, Pasarell, and Lutz had spent time with the senator. News of Kennedy’s shooting came while the team was in Charlotte, N.C., gearing up for a Davis Cup tie. While Dell rapidly left to be with the Kennedys, Pasarell stepped in as interim team leader.

Prior to that Davis Cup campaign, though, the bond between those four had been well-formed in Los Angeles, where this quartet played for college tennis’ two superpowers, UCLA and USC. Starting in 1965, the NCAA singles title was won over the next four years by Bruins Ashe and Pasarell, followed by Trojans Lutz and Smith. “That’s our private label rivalry that won’t ever go away,” said Pasarell.

What happened in 1968 further deepened their affinity (the fifth member of the squad, Clark Graebner, played superb tennis that year but was never as emotionally connected to his teammates). Much was fueled by Captain Dell’s hunger to bring the precious Davis Cup back to the U.S. for the first time since 1963. The film digs into that successful quest, capped off by the postscript of a January ’69 State Department tour to Vietnam, complete with hospital visits, helicopter rides over battle zones, and an increased awareness of the horrors of war in both its physical and political dimensions.

For make no mistake, Stan Smith has long possessed a social conscience that is concurrently spiritual and of this world. This comes across most clearly when the film shows the care and compassion he and Margie showed for Mathabane, a Black teenager growing up in South Africa under the thumb of that nation’s apartheid regime. Thanks largely to the Smiths, Mathabane was able to make his way to the United States and build a new life.

In a delightful coincidence that pleases storytellers, weeks before learning about the May 3 movie premiere, a friend had invited me to be his guest and play tennis on May 7 at the Los Angeles Tennis Club. This was Smith’s training ground, first as an adolescent, then in college, where his USC team practiced and played its matches.

Smith had been the last of the club’s great male champions, a chain of excellence that began with Ellsworth Vines and continued with such all-timers as Bobby Riggs, Jack Kramer, and Pancho Gonzalez. My afternoon there was glorious. From hitting on the courts to strolling through the lobby filled with photos and trophies, it was joyful to occupy a place where this man known largely to the world for a piece of footwear had crafted his legend, one step at a time.

"Canadian Doubles." / MGM Studios

"Canadian Doubles." / MGM Studios

All through his youth, Joel Drucker knew he lacked the strength and skill to wield the elegant Stan Smith Autograph frame.

SIGN UP — YOU'RE ONLY AS GOOD AS YOUR SECOND SERVE.

RECOMMENDED

Sinner’s Strange Summer

PARIS 2024 OLYMPICS

Novak’s Big Moment

PARIS 2024 OLYMPICS

Newport Takes a Bow

NEWPORT