No Fairy Tale

No Fairy Tale

Reappraisal: Carnival at Forest Hills by Marty Bell.

Reappraisal: Carnival at Forest Hills by Marty Bell.

By Joel DruckerSeptember 4, 2025

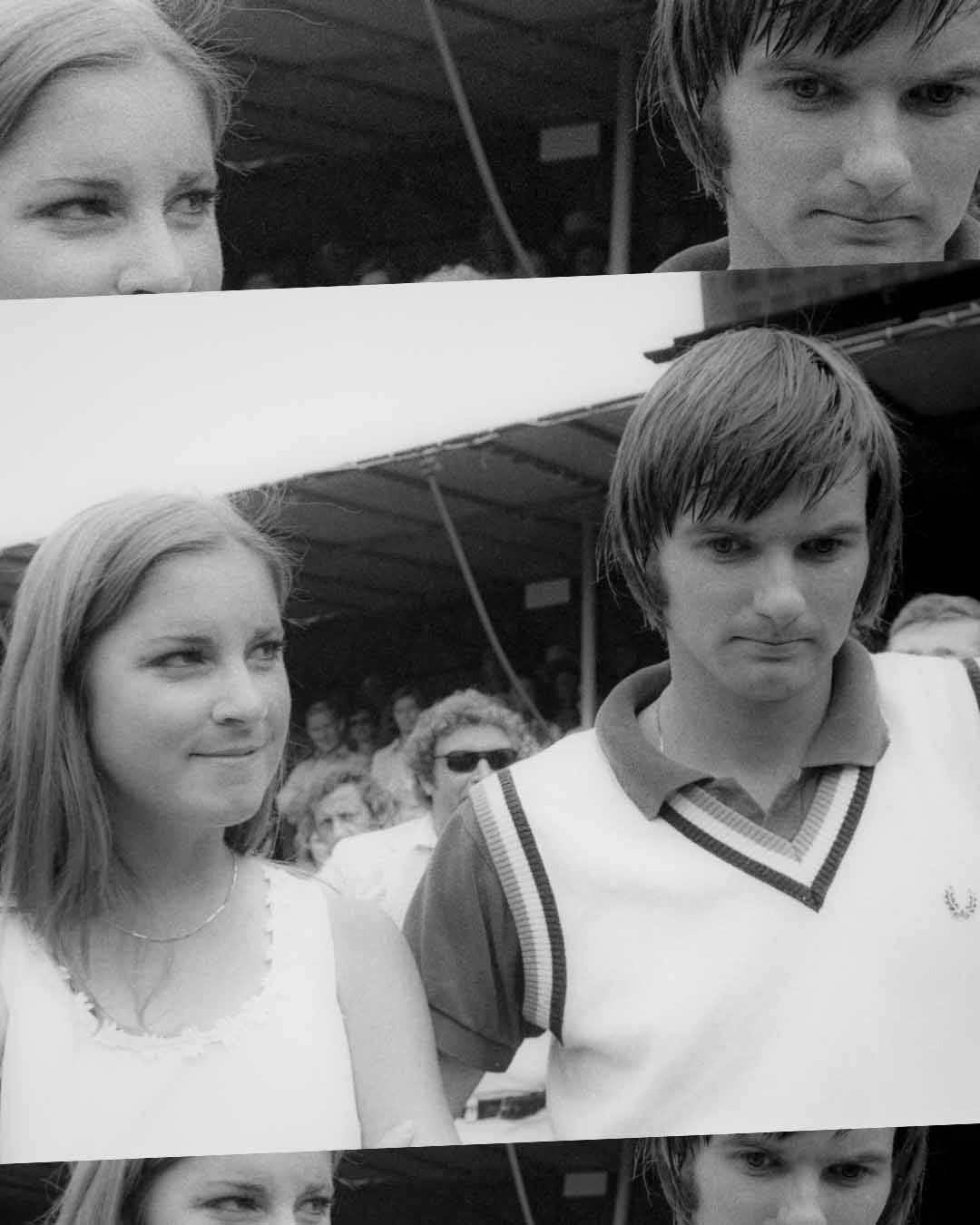

Chris Evert and Jimmy Connors, who were very briefly “America’s Sweethearts”. // Getty

Chris Evert and Jimmy Connors, who were very briefly “America’s Sweethearts”. // Getty

My weekend prior to this year’s US Open was spent at the induction ceremony of the International Tennis Hall of Fame. Located in Newport, R.I., this subdued and cozy venue had housed the U.S. National Championships until 1914. The Sunday morning following the ceremony, I headed west and south across New England and into New York to cover the US Open at the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center—a locale arguably not subdued and cozy enough.

Alongside those trips came a journey to a time and place theoretically in the middle. It happened in the form of rereading a book titled Carnival at Forest Hills. This is the tale of the 1974 US Open, played then at the West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills, a genteel neighborhood in Queens. Does that make this venue just right? Given what was going on in tennis then, think twice before you bathe yourself in nostalgia.

Consider the decade from 1968 to ’78 tennis’ Transitional Era. Nineteen sixty-eight marked the commencement of Open tennis, amateurs and pros at last unified, the sport now entering the contemporary sports world of commercialism. In the United States during that time, participation in the game tripled. By ’78, tennis’ growth was in large part symbolized by the US Open relocating to the current public facility at Flushing Meadows.

Carnival at Forest Hills captures the Transitional Era smack in its tumultuous middle. “Old-time members must have been as dismayed as the old-line Washingtonians in 1829,” writes author Mary Bell, “when Andrew Jackson opened the White House to the public and invited his frontier friends to a wild inauguration party. Tennis had become democratized.”

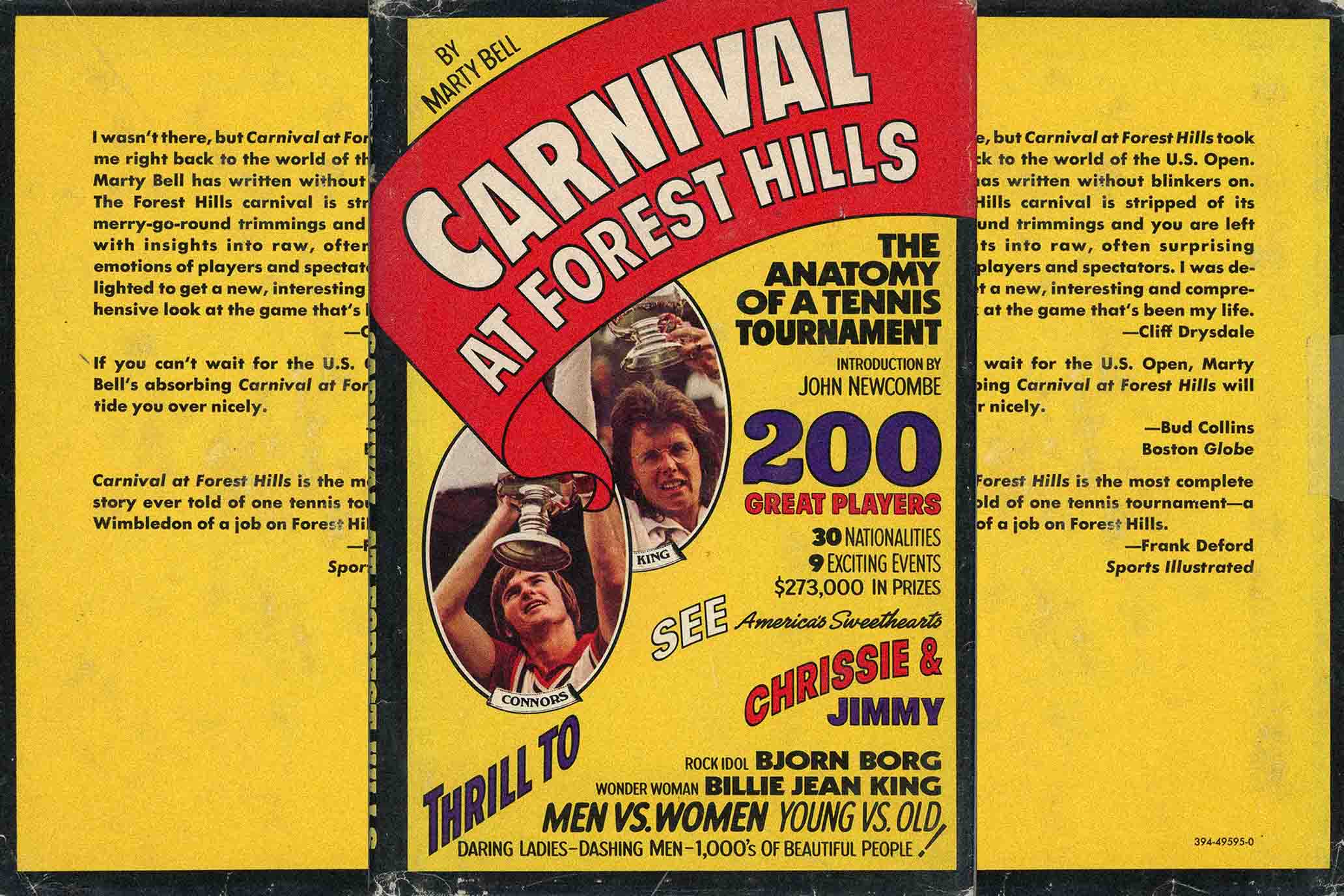

To further extend that 19th-century, P.T. Barnum-like quality, savor the book’s poster-like cover. The title is splashed in white letters against a red background and a bright yellow full page. The top seeds, Jimmy Connors and Chrissie Evert, engaged to be married at the time, are referred to as “America’s Sweethearts.” Bjorn Borg: “Rock Idol.” Billie Jean King: “Wonder Woman.” All joined by “1,000’s of Beautiful People.”

Remnants of tennis’ feudalistic past remained, ranging from the erratic bounces of the grass courts, to players expressing anger at how they were treated by haughty amateur officials, to the words of a volunteer linesman who lamented the increasing presence of money. There was also tremendous intimacy and access, with players, officials, fans, and media spilling over one another as they packed themselves into the West Side Tennis Club. The presence of such sporting Australians as the swashbuckling defending champion John Newcombe, his best friend/doubles partner Tony Roche, and the relentless genius that was 39-year-old Ken Rosewall (a stylistic ancestor to Roger Federer) served as reminders of tennis’ tradition of sportsmanship, elegance, and cucumber-like cool in the heat of battle. “Rosewall, as always impeccably groomed and dressed in his lucky yellow shirt and wristbands,” writes Bell, “seemed to spend the first set studying his opponent’s game.”

Then there was the new. The 1974 US Open marked only the third year that players were permitted to wear non-white clothing, hence a lively, quintessentially ’70s Technicolor showcase of pink, red, blue, yellow, and more. It was also the fifth year of the tiebreaker, in those days a rapid-fire version played to five points (no two-point lead). The next year, the tiebreaker would make an incremental shift to the seven-point version now employed. But one ’74 US Open protocol is long gone: winner and loser occupying the same room during a post-match press conference. Following a round-of-16 loss to Connors, ’73 finalist Jan Kodes declared in front of Connors’ face that “In my opinion, only two players are left in the tournament who I think can win: John Newcombe and Stan Smith…. I think Jimmy has third place.”

But while tennis experimented with such transitory elements as new garb, scoring systems, and player-press interactions, Bell observed something far deeper that was altering the complexion of the sport. While once the circuit consisted of a fraternal flock of solo acts circling the globe together, such top players as Connors and Evert had begun to change that dynamic. “[Connors] and Chrissie came to this and every tournament completely surrounded by a group of people whose only purpose was to guide them to the championship,” writes Bell. “The shell isolated them from everyone and everything else.” So began what’s become even more prevalent these days.

That was just one observation that delivers more depth than the book’s breezy title would lead you to believe. Neither raffish nor jaded, Carnival is concurrently highly readable but also quite thoughtful. Having read dozens of sports books authored in the late ’60s and early ’70s, I’ve long noticed in works of those years a compelling mix of appreciation, engagement, access, and analysis. Thanks largely to the growth of television, sports at that time had become popular enough to warrant broader sociocultural assessments—but not so big to the point where athletes were kept distant from the press and public. A writer like Bell could easily observe and chat with many tennis players, including even the very best. That’s hardly the case now, when players are mostly available during frequently sterile post-match press conferences and prefer to tell their own stories via social media. Over the years, that increasing distance has made many a journalist jaded, cynical, and occasionally even bitter about how the cocoon makes it difficult to write great stories.

No such rancor is present in Carnival. As Bell follows the tournament, day by day, making concise dives into selected matches of interest, his affection for tennis endures. Writing about a gem of a semi between Evert and Evonne Goolagong, Bell writes that “Now on point after point, they just stood back at the baseline, hitting as hard as they could for as long as they could.” In addition to match analysis, there are snapshot-like portraits of such notables as Arthur Ashe and his quest for more Grand Slam glory, Stan Smith’s mid-career crossroads, Goolagong’s alluring playing style, Newcombe’s charismatic personality, Borg’s popularity, and many others.

As you’d expect when reading about a competitive endeavor, those who win most emerge as the lead players. In the case of the 1974 US Open, those spots were filled by the eventual singles champions, King and Connors. Bell adroitly parses the polarizing qualities of each, albeit for drastically different reasons—King for leadership skills that some perceived as overly bossy, Connors for his highly isolated manner. “What are friends?” Connors asks Bell as they chat on the deck of the club. “I’d rather have a dozen good friends than a hundred who stab you in the back.”

Lest you think Connors has always been a New York darling, that was far from the case in 1974. During Connors’ 68-minute 6–1, 6–0, 6–1 victory over Rosewall in the final, a fan yelled out, “Connors, you’re a bum.” But as Bell writes, “The jeers from the stands only seemed to encourage him to be meaner and more aggressive. And he could always look to the marquee where the inner circle huddled together.” Bell went so far as to compare Connors to Richard Nixon, the American president who’d resigned a month prior. As Bell saw it, Nixon and Connors were both ambitious, tenacious, and uncouth competitors.

In the spirit of the best primary sources, Carnival vividly demonstrates how even then, the tennis world was hardly innocent. Open tennis had triggered both opportunities and challenges. To this day, the sport continues to wrestle with that legacy.

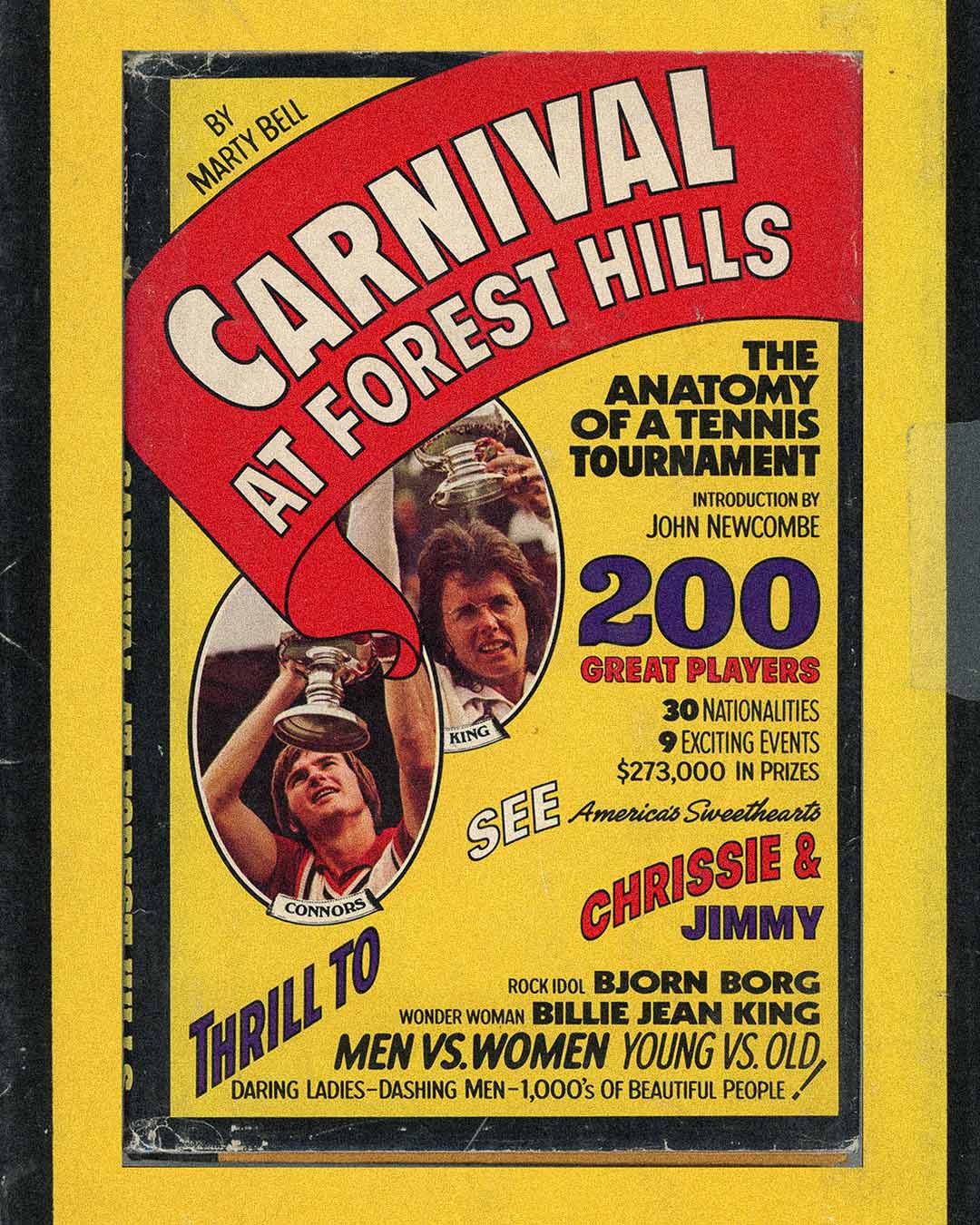

Carnival at Forest Hills by Marty Bell.

Carnival at Forest Hills by Marty Bell.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

RECOMMENDED

The Happy Slam Is in a Funk

AUSTRALIAN OPEN

Iva Jovic: A Calm Contender

ATP + WTA

The 2026 Australian Open Shoe Report

SHOE REPORTS