The Overthinker

The Overthinker

For the past three seasons, it's been more struggle than smooth sailing for Iga Swiatek.

For the past three seasons, it's been more struggle than smooth sailing for Iga Swiatek.

By Owen LewisFebruary 19, 2026

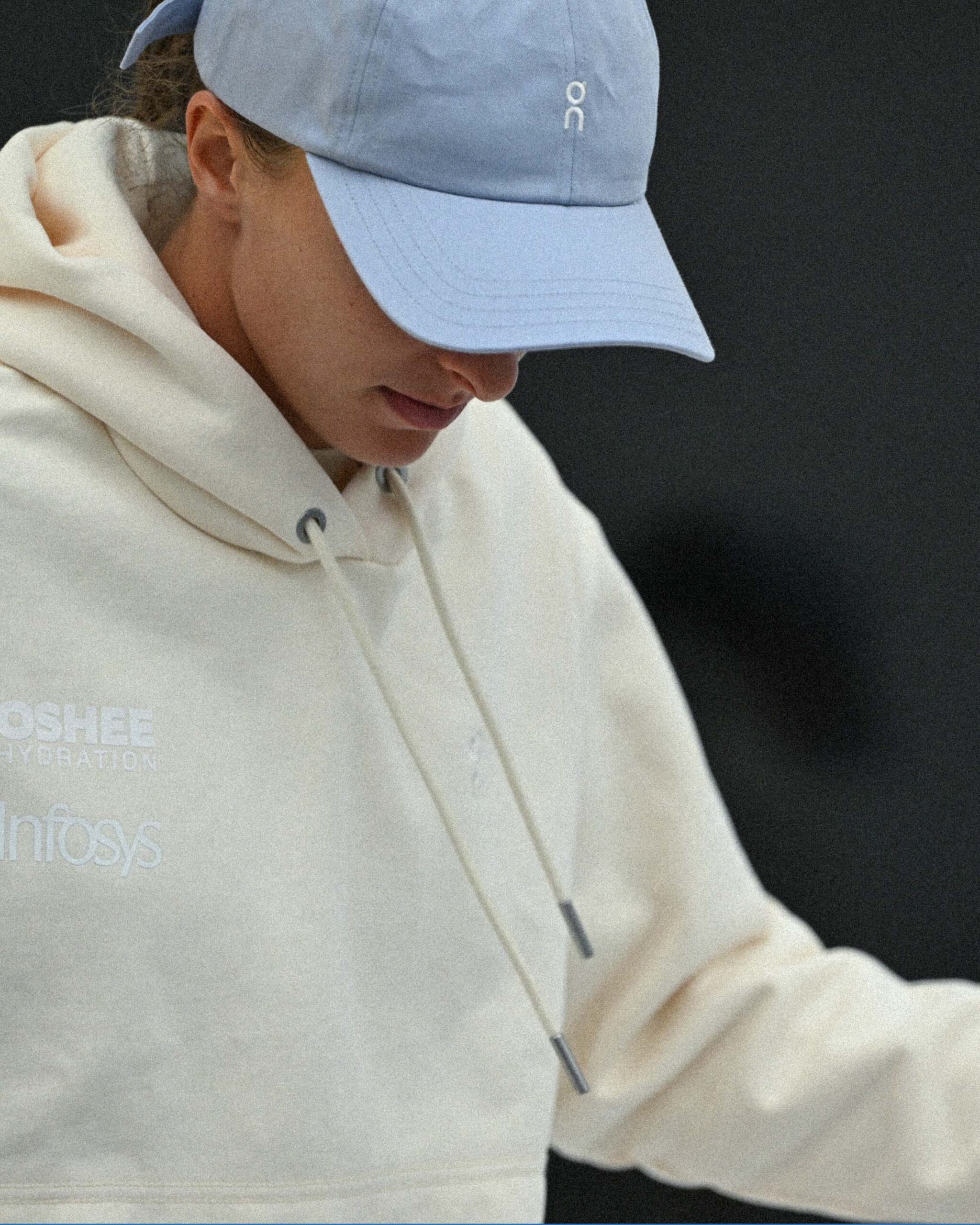

Iga looks for answers in Doha last week. // Getty

Iga looks for answers in Doha last week. // Getty

Let’s get this out of the way at the top: Iga Swiatek has six majors and 125 weeks at No. 1 at 24 years old, is iconic for brutalizing opponents (she lost all of 10 points in the fourth round of Roland-Garros in 2024), and is historically great on clay. Barring Aryna Sabalenka suddenly becoming automatic in major finals (lol) or Coco Gauff beginning to win majors in bunches (we’re just a serve and a forehand away), Swiatek will go down as the player of her generation. Last year, Swiatek completed an annihilating Wimbledon victory by winning her last three sets of the tournament 6–0. Any problem with Swiatek’s tennis is both relative and, let’s be honest, a convenient way to spin what is really just something interesting to talk about: When Swiatek has struggled—and she has struggled a lot, especially in the last year and change—the struggles have felt like they were about her identity as a player and her happiness as much as her results. It’s even felt like Swiatek has done more struggling than smooth sailing for the past three seasons, which feels ridiculous to type because she has done so much smooth sailing. And yet…

Swiatek just lost to Maria Sakkari from a set up in Qatar, which ended her career-long never-lost-from-a-set-up-at-a-1000-level-event streak. If you watched Swiatek play Sakkari anytime after 2021, you also probably never thought Swiatek would lose to her again. Upsets happen and streaks end. But this loss came on the heels of a rather abrupt 7–5, 6–1 defeat to Elena Rybakina at the Australian Open. And a loss to Rybakina at the WTA Finals, in which Swiatek won only one game in the last two sets. And a 6–1, 6–2 loss to Jasmine Paolini in China. And sets she lost 6–0 to Emma Navarro and Belinda Bencic. And a streak of eight sets and counting she’s lost to Coco Gauff, whom Swiatek won 11 of her first 12 matches against. She isn’t regularly going deep enough in tournaments to get to Aryna Sabalenka, so nobody really knows where that rivalry stands. It feels like most top players, who lived in fear of Swiatek when she crushed the tour in 2022, now relish playing her and produce their best tennis accordingly. Swiatek destroyed the field at Wimbledon last year and followed that triumph with titles in Cincinnati and Korea, a hot streak ended the wintriest six months of Swiatek’s career to date. Now summer seems over once again. So let’s talk about this.

Iga Swiatek wants to win tennis matches so badly. It’s why her routines are intense enough to be a little bit uncomfortable, whether that’s her jumping by the net during the coin toss, her religious consistency in taking bathroom breaks after the first sets of her matches, or the way she looks like she is rapidly cycling through the five stages of grief when a match starts to slide away from her. It’s why when she does win, it’s impossible to imagine another outcome because it feels so natural. It’s why she didn’t give Amanda Anisimova a game in the Wimbledon final last year and found the suggestion that she could have insane. I think it’s why she used to try to distract opponents by waving her arms when they went to hit a putaway—unconsciously!—and had to try to train herself out of the habit once she realized she was doing it. It’s why she bounced a ball hard into the ground, skimming it close to a ballboy’s head, in the midst of losing to Mirra Andreeva at Indian Wells a few months before that. It’s why her statement afterward—sort of an apology, but mostly a long meditation on how fucking hard she was finding the whole tennis thing—felt more than a little bit tortured. It’s why she acknowledged in the statement that the realization she wouldn’t get a look at the No. 1 ranking for a while “deeply upset” her, which most players would not have admitted to being anything more than motivated by. (Almost a year later, Swiatek still isn’t sniffing the No. 1 spot.) It’s why Swiatek doesn’t get visible joy when her tennis excels in concert with her opponent’s, only satisfaction at the little successes and relief when she wins in the end.

It’s also, I’d posit, why Swiatek is not winning as many tennis matches as she’d like to right now. Swiatek is caught between styles, striving toward the varied and patient game with which she broke out in 2020, but trapped in the hyperaggressive baselining that saw her reign over the tour in subsequent seasons. Swiatek is one of the best movers on the WTA, capable of sliding into her shots from nearly any position. That defense can elicit errors from the best attackers. But lately, when she’s on the ropes, Swiatek abandons her defense entirely in favor of harder and harder ground strokes, which inevitably go awry. In errant hyperaggressive mode, Swiatek looks utterly miserable: aware of what she needs to do but incapable of doing it. (Hopefully she doesn’t make like Kylo Ren.) How many other godlike tennis players can we overthinkers relate to so closely?

This past week, I rewatched Swiatek’s first major final, a 6–4, 6–1 win over Sofia Kenin at Roland-Garros in 2020. Though just 19 years old back then, her patience astonishes. Her movement was already fantastic but was geared more toward setting trip wires for Kenin than ripping a winner from an improbable position. She was more than happy to spin defensive shots back, absolute in her confidence that Kenin would eventually miss. Some aggressive defense featured too, notably a backhand down the line that found the corner each time Kenin successfully yanked her outside the tramlines, though they were hit more out of necessity than aggression. She conjured a few backhand drop shots—not as a load-bearing part of her strategy, just one more way to win points—that all worked. At 15–30 down in the second set, she approached the net behind an inside-out forehand that was decent but certainly vulnerable to the pass, and clipped a confident volley winner. Yet she was still the aggressor, hitting 24 winners to Kenin’s 10! Swiatek accomplished all this without ever playing too hurriedly, and won in barely an hour.

Swiatek and the tour have changed so much in the past five years and change that it’s hard to blame her for being in a hurry now. She hired Tomasz Wiktorowski as her coach in the 2021 offseason, then promptly won 37 matches in a row in 2022. Her standard baseline game cut through the field so easily that those spontaneous drop shots and net rushes no longer seemed necessary. But the tour proceeded to get significantly stronger in the coming years. While Swiatek’s defense could have returned a lot of power players’ blasts, she elected to try to match their offense rather than accept the role of chaser. She’s had plenty of success but has lost the game with which she broke out in the process. In late 2024, Swiatek parted with Wiktorowski and hired Wim Fissette, who wanted to bring that old game back. Despite some early promising signs, the search continues. At the Australian Open last month, I asked Swiatek how she felt about her game relative to when she exited the tournament last year.

“This year we didn’t manage to, like, completely close the stuff that we wanted to change in the preseason. It just got a bit longer for me to change some stuff, you know. So this year I felt like I also needed to work on it during the tournament, and that’s why maybe, I don’t know, I felt like I played, like, tiny bit worse,” Swiatek said. She added that she didn’t think that mattered, but come on, making the quarterfinals while actively tinkering with your game beyond the usual match-to-match tweaks deserves a trophy of its own. It’s rare that anybody’s tennis is exactly where they want it to be, but Swiatek’s doesn’t feel particularly close.

Swiatek’s plight is fascinating—she’s in search of a brand of tennis that once was natural but has been dormant for long enough to become inaccessible. It’s still in her somewhere. In the second set of her Roland-Garros semifinal with Sabalenka last year, Swiatek hit perfectly weighted drop shots on consecutive points, from compromised positions (and right after consistent Iga skeptic Chris Evert shaded her touch). Can we reunite with parts of ourselves that are lost to time if we work hard enough to dig them up? In the late years of his career, Andy Murray retained many of his scrambling abilities but could not, try as I’m sure he did, compensate for what he lost by just banging the damn ball. It’s hard, so hard, to grant yourself mental permission to deviate from the strategy that has served you well for years. Swiatek is at least trying to deviate back to a software she’s implemented before, but that doesn’t seem to be any easier.

The match point from the Sakkari loss will stick with me more than the defeat itself. Swiatek had the point in her pocket. She ripped a forehand down the line that Sakkari could only reach with a desperate, floaty slice backhand at the very end of her range. Swiatek charged the net to clean up. Had she run straight at the ball, she’d have been there in plenty of time to spike it into the ground for a winner. But she ran around the ball instead, intent on hitting a forehand volley, and the ball dipped below the height of the net by just enough that Swiatek couldn’t clear it. I imagined her younger self racing along a more direct path to hit the correct shot, secure in her identity as a player and unburdened by all the pressure to follow. Wanting something too badly usually precludes you from getting it, so perhaps the way forward for Swiatek is to crave winning a little bit less. But then, that would deviate from her identity as well.