Home Is Where the Gold Is

Home Is Where the Gold Is

For some athletes, nationality can be tricky….or an opportunity.

For some athletes, nationality can be tricky….or an opportunity.

By Ben RothenbergAugust 7, 2024

Naomi Osaka represented Japan at the Olympics. // Getty

Naomi Osaka represented Japan at the Olympics. // Getty

As they sat next to each other on a bench in Paris Monday night, a guy from Mississippi offered a guy from Louisiana some distinctly Southern medical advice for how he might patch up the cuts on his ragged right hand.

“I’m not putting no damn duct tape on it,” the guy from Louisiana replied.

A few minutes later, “The Star-Spangled Banner” played and both men stood with their right hands over their hearts. Sam Kendricks, the guy from Mississippi who had competed for Ole Miss, had his hand covering the S and A of the “USA” written across his shirt; Armand “Mondo” Duplantis, the guy from Louisiana who had been a star for LSU, had his hand covering the E and N at the end of “SWEDEN.”

The story of the world’s best pole-vaulter will ring familiar for American tennis fans: An enormous homegrown talent opted to represent greener shores overseas.

Duplantis, born and raised in Lafayette, Louisiana, where he grew up with a pole-vault pit in his backyard, has improbably become the biggest Scandinavian star of the 2024 Olympics, and arguably the biggest representing all of Europe.

_________

As it was for immigrants of various vocations, the United States was a popular destination for overseas tennis champions throughout the 20th century, with many of the best switching to representing America during their careers. In the amateur era, the champion Molla Bjurstedt Mallory switched from representing her native Norway to representing the United States midway through winning her eight US Open titles, spanning 1915 to 1926, after marrying American stockbroker Franklin Mallory.

More dramatically, an 18-year-old Martina Navratilova had defected to the United States early in her career after a loss in the semifinals of the 1975 US Open, requesting political asylum so she could escape the Communist regime in her native Czechoslovakia, which was exerting strict control on her tennis travel. Navratilova won all 18 of her major singles titles as an American. Other high profile transfers to the United States came later in careers: Both Czechoslovakia’s Ivan Lendl and Yugoslavia’s Monica Seles acquired U.S. citizenship and switched to representing the United States as their respective countries disbanded in the 1990s.

But after the Cold War thawed out, the growing number of players who moved Stateside to chase their tennis dreams at Florida academies were no longer commensurately changing their allegiances along with their addresses. Most famously, Siberia-born Maria Sharapova moved to Florida at age 7 with her father, Yuri, and has lived in the United States ever since. She fit in with the locals right away, speaking English with no trace of a foreign accent and acquiring major American sponsorship deals. But though many Americans suggested Sharapova would fit right in, she remained representing Russia for her entire career. “I felt like Maria shoulda-coulda have played for the United States,” Mary Joe Fernández, the longtime U.S. Fed Cup captain, told me. “But, you know, we get some, we don’t get some.”

Sharapova rarely played for the Russian Fed Cup team, and played few tournaments in Russia, but her successes at the Grand Slam events meant she remained one of Mother Russia’s favorite daughters. At the 2012 Summer Olympics in London, Sharapova was chosen to carry the Russian flag in the opening ceremony. At the 2014 Winter Olympics in her former hometown of Sochi, Sharapova was picked to carry the torch into the stadium during the opening ceremony.

Sharapova said in a 2015 interview on CNBC that the idea of switching to represent the United States wasn’t something she or her family had ever seriously considered. “I would have if I wanted to,” Sharapova said, “but it’s never been, actually, a question in my family or in my team whether I wanted to change citizenships.” Sharapova, whose sponsor portfolio never relied on any major Russian deals, said she felt tied to Russia because of its “rich culture” as well as the childhood years she spent there that she still considered formative. “I know that for so many years I was shaped into the individual I was from those experiences,” she said. “And not necessarily simply the country, but the people, the mentality and the toughness and that never giving‐up attitude.”

Though she never wavered from her official Russian identity, her apparent Americanization was scrutinized and lamented back in Russia. In 2018, Sharapova posted a picture of her mother and herself standing with their arms around each other in front of an artwork at The Broad, a Los Angeles art museum: one of Jasper Johns’s paintings of the American flag. The image caused strong divided reactions from Sharapova’s Russian followers, who debated in the comments if the image was unpatriotic or disloyal. “Masha is no longer ours,” one Russian commenter rued. “She will never return.”

After Sharapova, the USTA’s reputation for laissez faire came into sharp relief in 2013, when for the first time in the 40year history of the ATP rankings there were zero American men ranked inside the top 20. There were, however, several players inside the top 20 who lived in the United States, including the dual citizen German-American Tommy Haas and U.S. permanent resident Kevin Anderson, who represented South Africa.

Haas, who had lived in the United States since he was 13, said he wouldn’t mind being counted as an American to help shore up the ranks, “In many ways I feel like I am, so maybe you guys should too,” he said.

But Patrick McEnroe, then the general manager of player development for the U.S. Tennis Association, told me that persuading foreign-born players to join forces with his federation was not something he would do in his role. “I would love for Tommy Haas to be an American, but that’s his call,” McEnroe said. “I know that he thought about that a couple of years ago. But at least from my perspective with the USTA, I can tell you that we don’t pursue any players that have that dual citizenship. I would never go to Tommy Haas and say, ‘Hey, I really want you to play for the U.S.’ In my role with the USTA, I wouldn’t do that.”

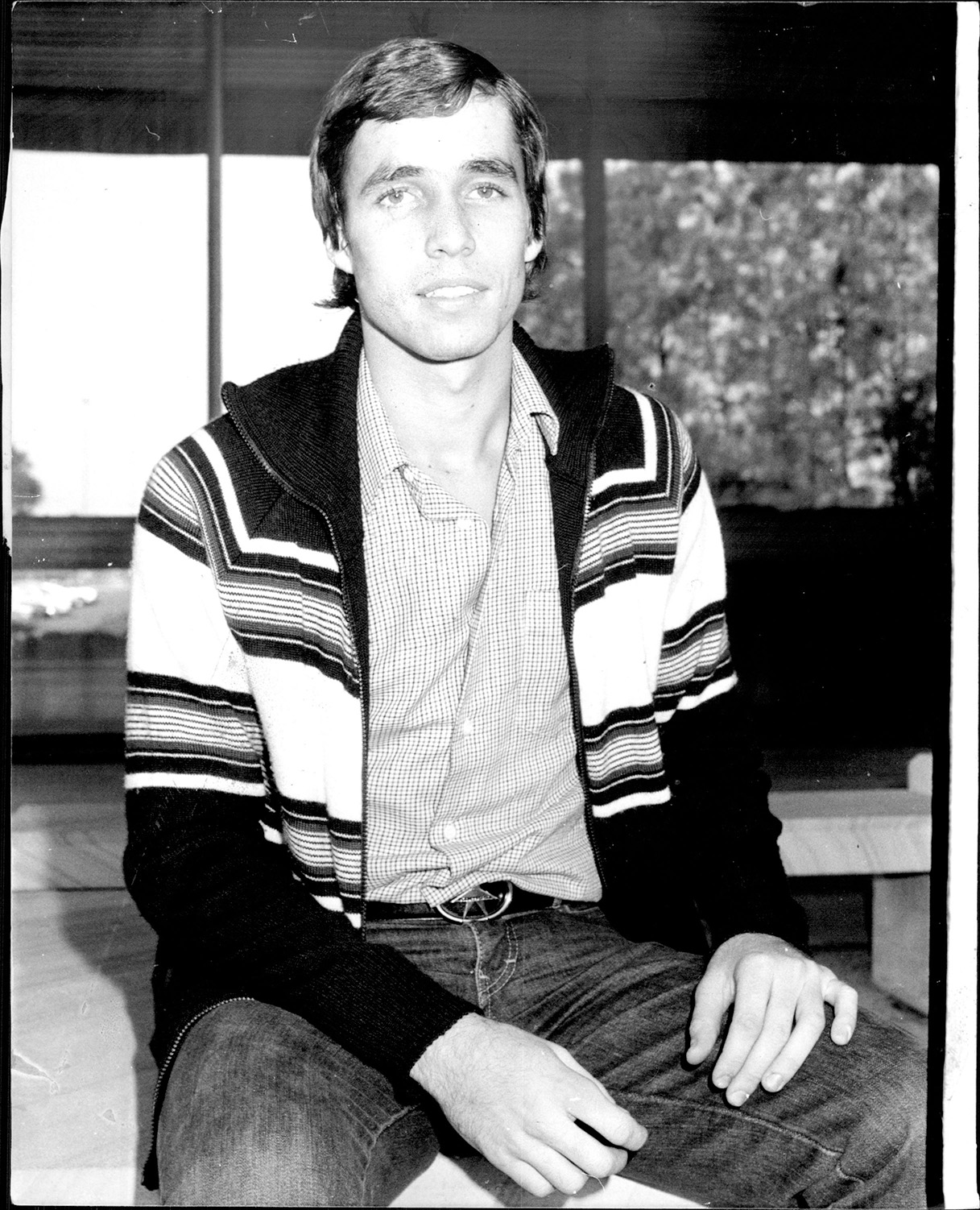

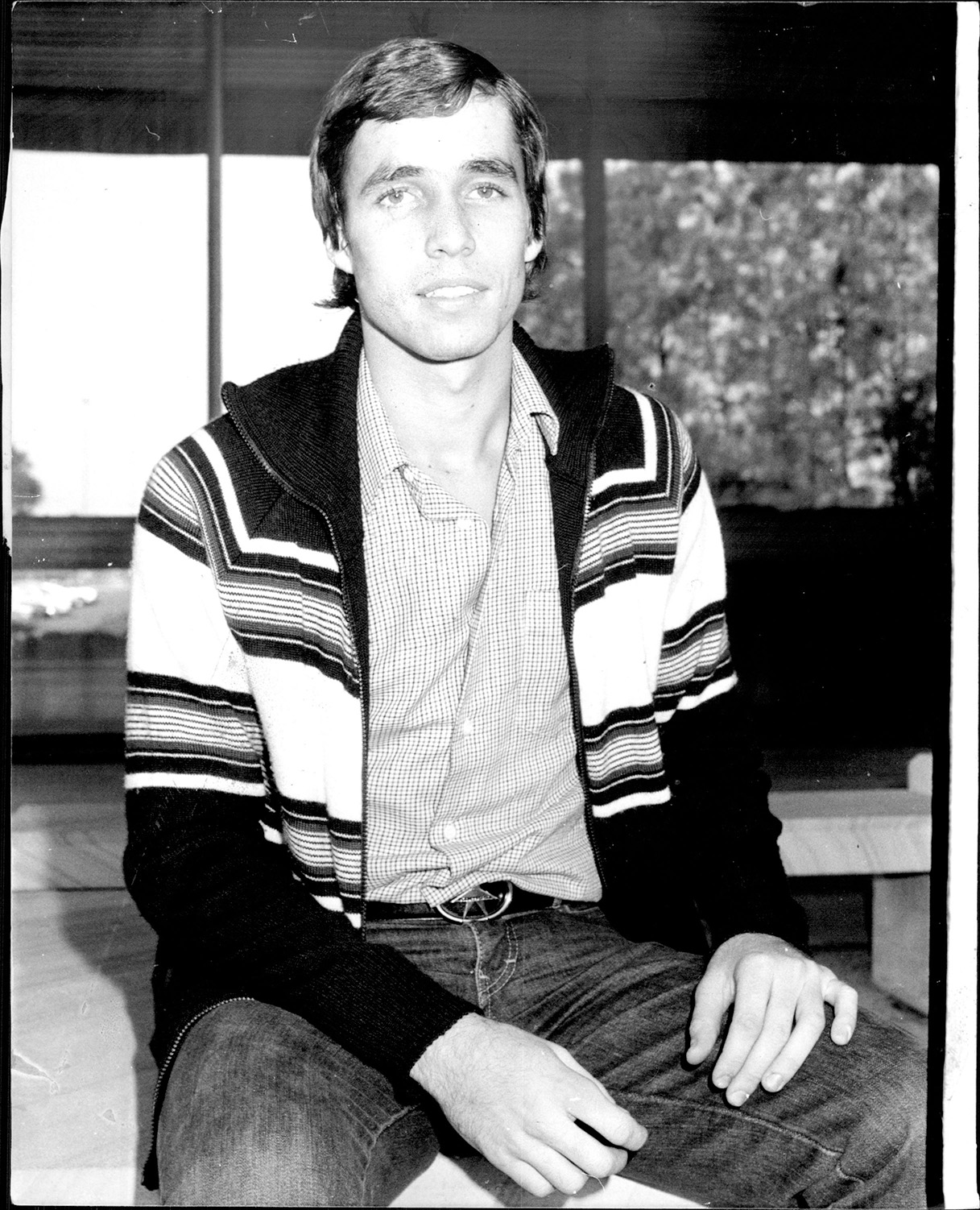

Sam Kendricks and Armand Duplantis are from Mississippi and Louisiana respectively. // Getty

Sam Kendricks and Armand Duplantis are from Mississippi and Louisiana respectively. // Getty

As the trend continued, it wasn’t just that foreign players weren’t choosing to switch to America anymore in the 21st century; many Americans were choosing to replant themselves on other soil, betting they could blossom more fully in less crowded crops.

Monica Puig would not have qualified for the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympics had she chosen to continue representing her longtime home of the United States, as she had at the start of her junior career; Puig, a Floridian for years, was ranked 49th when the cutoff was made for the 2016 Olympics, well below the quartet of top Americans who were taking the country’s four allotted spots. But because Puig had chosen early in her career to represent her birthplace of Puerto Rico, the U.S. island territory that has had its own separate Olympic committee since 1948, she was able to secure a spot in the exclusive draw under the Puerto Rican flag. Puig made the most of the opportunity: Playing the best tennis of her life, she stunned the field to win Puerto Rico’s first gold medal in any event in Olympic history. (Puerto Rican Gigi Fernández had won two Olympic gold medals in women’s doubles in the 1990s, but representing the United States.) The United States won 46 gold medals in Rio de Janeiro; an additional 47th won by Puig for the Stars and Stripes might’ve gained little notice. But playing for Puerto Rico, Puig was immortalized on the island as a sporting hero.

Even Americans born in the United States have been increasingly lured away in recent years. Ernesto Escobedo, a native Los Angeleno with a booming forehand, reached a peak ranking of 67th in 2017, then the ninth-best among American men. By January 2023, Escobedo’s ranking had slipped to 310th, behind 27 other American men. But on his way to battling through the Australian Open qualifying draw, Escobedo suddenly became his nation’s top player—because midway through the tournament his flag had officially switched to Mexico, a country with no other men ranked inside the ATP top 500 in singles.

“It’s always been in me that I wanted to play for Mexico, you know? Like, always, my whole life,” Escobedo said in a January 2023 interview with Mike Cation on the Behind the Racquet podcast. “Even if I was born in the States, in L.A., I was raised as a Mexican. I was raised with a culture, a Mexican culture, with my family, and I’ve always enjoyed going back to my [family’s] hometown in Zacatecas.” In many ways it was an obvious choice. Escobedo had told The New York Times he had been embarrassed to have the American flag beside his name after the racist, anti-Mexican rhetoric of Donald Trump had been a cornerstone of his winning presidential campaign.

________

The trend of Americans opting to play for ancestral homelands has been most pronounced among Asian-Americans, with U.S.-born players like Jason Jung (Taiwan), Ena Shibahara (Japan), and Treat Huey (Philippines) all becoming some of their country’s biggest stars this century.

The most prominent case of an Asian-American tennis star opting to play for another country, of course, is Naomi Osaka, who was born in Japan but moved to the U.S. as a toddler when she was 3.

No one would have doubted the Americanness of the Osaka sisters: They were natural-born as American citizens through their father Leonard Francois’ American citizenship and had lived in the United States since their early childhoods. But once Mari and Naomi started entering professional events, for which players were required to list a single nationality on tournament entry forms, they consistently affiliated themselves with Japan. When Naomi had made her professional debut in Jamaica just before her 14th birthday, as a dual citizen who had lived for more than a decade in the United States, it was “Naomi Osaka (JPN)” listed on the draw sheet. That pivotal decision, which was reconsidered and pondered but ultimately never changed, had profound effects on Naomi’s career.

“We were talking about that a lot,” Daniel Balog, Naomi’s first agent, told me of the dilemma of which country Naomi should represent. “We were thinking: In case it really takes off, which market is better? And we were thinking of the United States, I’ll tell you. There was definitely a lot of talk about it.”

The commercial success of Kei Nishikori, Balog told me, was a major consideration. “You saw that he was an absolute superstar in Japan,” said Balog. “Obviously the Japanese market is massive if you are very good, and they’re willing to really get behind you…. And it was less competitive on the Japanese side because she was the lone star. With the United States, there’s so many good players, right? You’d compete against Serena, Madison Keys—so many. So I think it was a good move; I think it was great.”

Katrina Adams, who served as president and chairman of the USTA for two terms from 2015 to 2019, similarly to McEnroe, told me the USTA gave players space to make their own choices. “That’s the thing about America: You can be who you want to be,” Adams told me. “I can name 20 players that grew up and trained in America while becoming top 5 in the world representing other nations. But you are who you are. And so, yeah, [Naomi] lived in New York as a kid, but she’s Japanese. And that’s who she represents, and that’s her choice.”

Harold Solomon, an American who coached Osaka in Florida before her choice was cemented, had lobbied the USTA to recruit her but told me the overtures the USTA made to Naomi and her family were ultimately too little too late. “I think if the United States possibly had stepped up at the time and said, ‘Look, we’re willing to make this investment, we’re willing to do this or send a coach with her and help pay for her expenses,’ I mean, there’s as good a chance as not that they would have done the U.S. thing,” he said.

Years after Naomi Osaka and her parents made their choice, she won two US Opens and two Australian Opens under her belt, and questions about how America missed out on this generational champion swirled. Osaka has gone on to win more major singles titles than any other player born in the 1990s, and more than any other Asian. While she has remained based in the United States, only occasionally visiting Japan, she has been embraced by the country. In Tokyo in 2021, Osaka was picked to be the first tennis player to light the cauldron at an Olympic opening ceremony.

Ivan Lendl in 1980, when he still represented Czechoslovakia. // Getty

Ivan Lendl in 1980, when he still represented Czechoslovakia. // Getty

Osaka lost in the first round of these current Olympics, ceding the spotlight to stars like Duplantis to have their own biographies more widely learned. Duplantis’ mother, Helena, was born in Sweden, and Duplantis decided to represent the country in his early international career, despite having never lived in the country and not speaking the language. But after he switched, and after his breakout success made him one of Sweden’s most famous sportsmen, he studied Swedish intensively. When Duplantis won the 2020 Jerringpriset, the annual award given to Sweden’s top sportsman, the country was further won over by Duplantis giving his acceptance speech in Swedish. “When the Swedish people have finally given him their immense love, he gives it back to them and speaks the people’s language—BEAUTIFULLY!” said Swedish radio journalist Bengt Skött.

The reaction back in Duplantis’ home state of Louisiana has been considerably more mixed, making the obscure sport of pole vault into a local flashpoint for callers to debate on local sports talk radio. Scott Prather, a host on ESPN Lafayette Radio, told me that he pulls for Duplantis as a hometown hero but frequently hears from natives who don’t. “I don’t know that there’s anyone that actively roots for him to fail, per se,” Prather told me. “But I’ve heard some—even some that work in sports—that say, ‘Look, if he’s going up against an American in the Olympics, I’ll root for the American.’ And my response is, ‘But he also is, like, from right here, your hometown, you know?’ I’ll debate with them: ‘So he could go up against somebody that you know nothing about, in a sport you don’t watch, who is from the Midwest or the West Coast, and you’re rooting for the other one?’ And they’re like, ‘As long as it says “USA” on the chest!’”

“I don’t argue with them,” Prather added. “To each their own, but it’s a weird juxtaposition: There’s a part of you that you feel like you’re rooting local in terms of your roots in your country, but you’re not really rooting local in terms of what has been brought up in your backyard. I guess they view it as patriotism? I don’t have a problem with that. I don’t try to really change anyone’s mind, I just try to give them all the information.

“I don’t know how it is in Sweden for him. I hear it’s a little different,” Prather said. “But to be the best ever at something, and in your hometown not have the full support?”

Any bitterness over Duplantis’ defection among American sports fans should probably come off as greedy: Even without Duplantis, the United States has won 21 gold medals through Monday at the Paris Olympics, the most of any nation, with many more likely to pour in; Sweden has won only three.

________

But few of the American golds came with anything like Duplantis’ sparkle. A few minutes after he declined the duct tape suggestion on Monday night in Paris, Duplantis easily broke the Olympic record in pole vault, and then broke a world record of his own for the eighth time, clearing an unprecedented height of 6.25 meters—that’s 20 feet and six inches in Louisiana.

Kendricks, the guy from Mississippi, had topped out at 5.95 meters—nearly a foot less in Mississippi. Having claimed the silver for the United States, Kendricks spent the last half hour of the competition leading the cheers for Duplantis. A Greek guy from Athens—Greece, not Georgia—rounded out the podium with bronze.

Amid the excitement and celebration at Duplantis’ gravity-defying feats, there was bafflement on both sides of the Atlantic. Many European fans couldn’t understand why a Swedish superstar had been so reverent to the American anthem, which was playing as 100-meter-dash gold medalist Noah Lyles stood atop the podium on the other side of the Stade de France. Many Americans couldn’t understand why a guy from Louisiana was decked out in Swedish blue and yellow, setting records for another country.

Thousands of Swedes flocked to Paris to watch Duplantis, dotting the stands of the Stade de France with yellow. Many wrote messages for him across their Swedish flags: “Kung Mondo” (King Mondo) read one horizontal stripe; others used the yellow cross to make mini crosswords of “Mondo/Flying Swede” or “Gold/Mondo.”

Once Duplantis had come back down to earth with another world record on Monday night, he ran a victory lap with the enormous Swedish flag his father had handed him floating behind his shoulders. The DJ inside the Stade de France played a track they might have labeled as the Swedish national anthem: “Dancing Queen” by ABBA.

Maria Sharapova was the torch-bearer at the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, her hometown. // Getty

Maria Sharapova was the torch-bearer at the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, her hometown. // Getty

Editor’s note: This piece was adapted from Naomi Osaka: Her Journey to Finding Her Voice and Her Power, by Ben Rothenberg