Good-Time Charlie

Good-Time Charlie

A review of Being Carlos Alcaraz: The Man Behind the Smile by Mark Hodgkinson.

A review of Being Carlos Alcaraz: The Man Behind the Smile by Mark Hodgkinson.

By Patrick J. SauerAugust 28, 2024

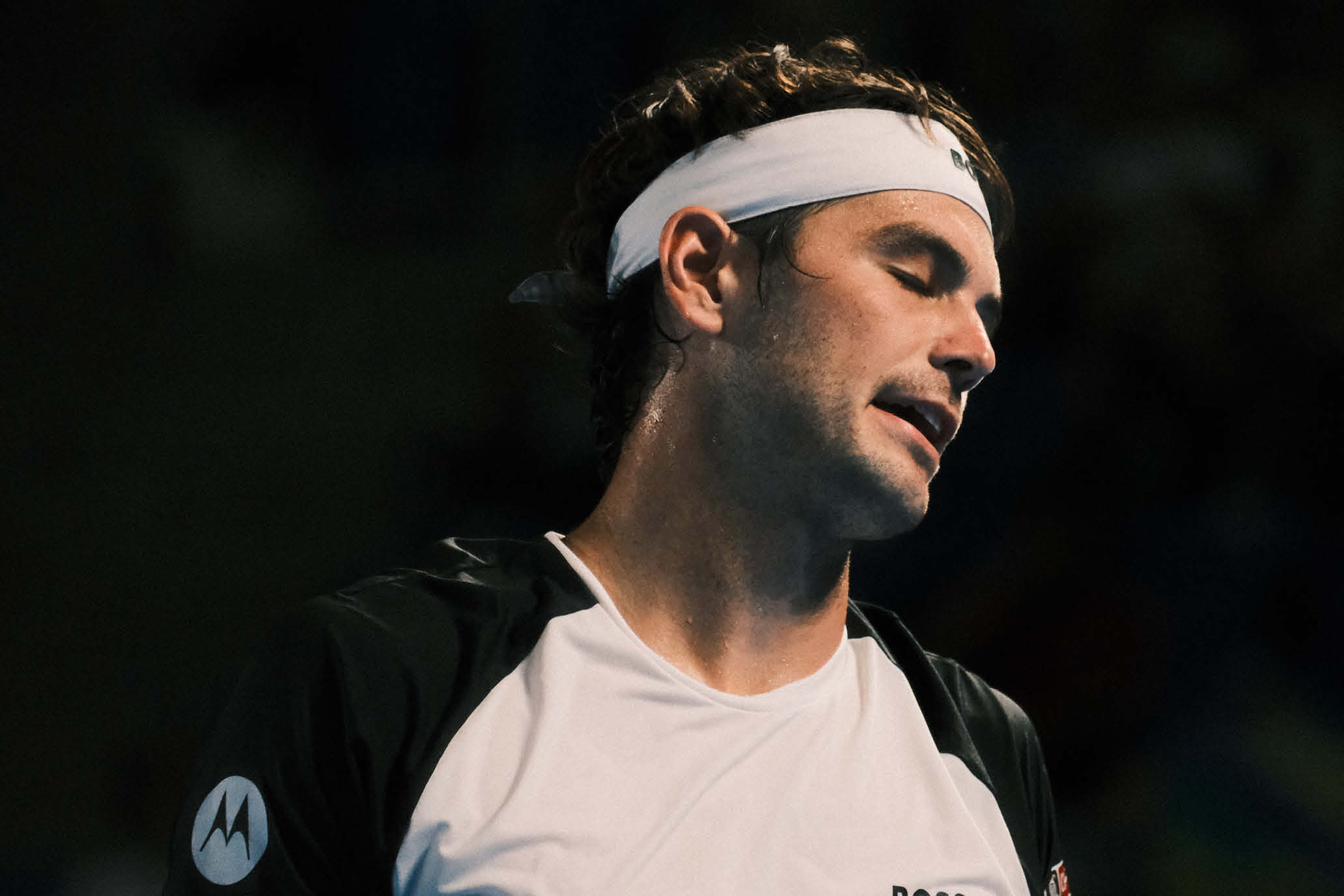

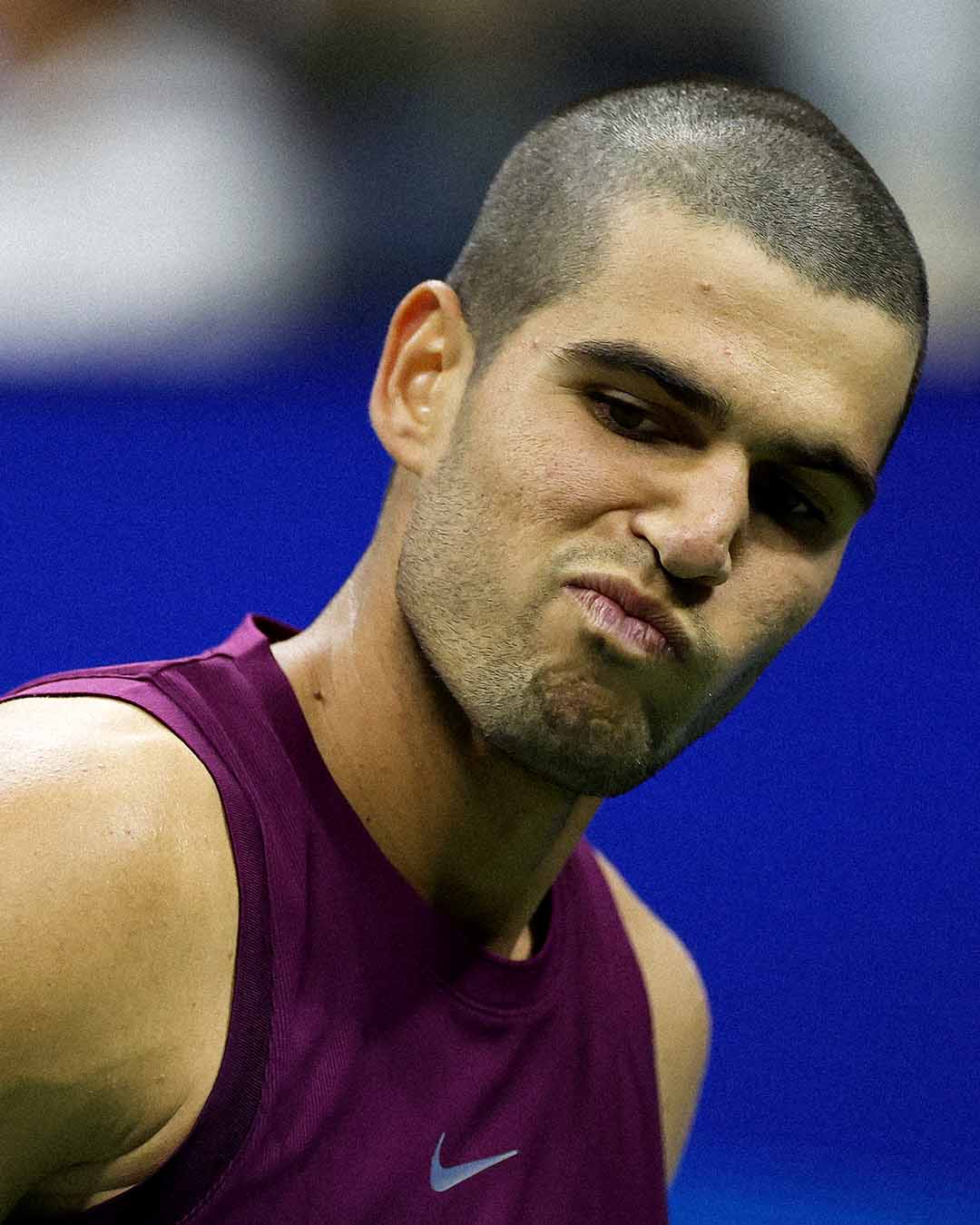

Carlitos mugs during his second round win at the US Open this week. // Getty

Carlitos mugs during his second round win at the US Open this week. // Getty

October 1 marks the 50th anniversary of the famed “Thrilla in Manila,” a brutal slugfest won by Muhammad Ali after Joe Frazier didn’t come out of his corner for the 15th round. It concluded the greatest trilogy in boxing history, still talked about with awe even though both the Greatest and Smokin’ Joe died during the Obama era and the sport itself has barely gotten up off the public consciousness mat since the previous century. There remains something particularly scintillating about an epic mano a mano best-of-three that goes the distance because the competitors, actual or metaphorical heavyweights, know each other’s styles and tendencies, strengths and weaknesses, equal beauty in the athletic ballet and the war of attrition.

Which is why everyone on tennis earth—even, I’m guessing, some of the actual men’s players currently in the US Open—wants to see Carlos Alcaraz and Jannik Sinner enter the ring on Sept. 7 for the “Clash at Ashe,” which would indeed crown the No. 1 ranking. If it happens, the hype machine will kick into overdrive, bringing along two new books with it. The first one you may know already, Changeover by The Second Serve’s own Giri Nathan, a fantastic, propulsive, deeply considered look at the Sincaraz phenomenon.

The second tome is Being Carlos Alcaraz: The Man Behind the Smile by British writer Mark Hodgkinson, an early career biography of the 22-year-old five-time Grand Slam champion. Hodgkinson works as quickly as Carlitos goes baseline-to-net. His last book, Searching for Novak, came out just over a year ago. I didn’t care for it at all, but I will concede it was probably doomed from the outset given the subject/writer pairing. Hodgkinson has ghostwritten columns for some of tennis’ biggest names, has coauthored workout books with English movie stars and their trainer, and consults for sports brands in the U.S., Europe, and Japan. It isn’t a knock to say he doesn’t approach book-writing with the same critical rigor as a dyed-in-the-wool reporter, which is his chosen bailiwick, and fair enough when it comes to the fun-loving human labradoodle Carlos Alcaraz. Uttering nary a negative world about Carlitos is nowhere near the credulity of taking Novak and his people’s self-serving rationales for his self-induced trials and tribulations. Sure, the descriptor “humble” grew tiresome in Being Carlos Alcaraz, but it isn’t the uncut unctuousness of Djokovic acolytes comparing him to the literal Lord and Savior. And I say that as a devout nonbeliever.

It’s important to understand that Hodgkinson’s book is as much a Carlitos brand extension as My Way, the streaming series the author uses as a primary source multiple times (e.g., Verbatim, page 41: “‘There’s no food in the world like my mother’s, let me tell you,’ he said in his Netflix documentary in 2025”). He doesn’t interview Alcaraz or seemingly anyone in the inner circle, but he does talk to people who are one step removed and have been around him at various times, so at least the effusiveness is spread around. Spain tennis luminaries like Antonio Martinez Cascales, founder of the Ferrero Tennis Academy, the rural once-bare-bones club where young Carlos learned the game, and Alex Corretja, a Roland-Garros finalist in 1998 and 2001, offer equal measure of insights and platitudes to make Being Carlos Alcaraz a pleasant-ish diversion. Although in the “Titanito” pecking order (“Little Titan” being excellent sobriqueting on Joker’s part), the Netflix romp offers firsthand on-camera interviews with the mega-joy and occasional furrowed brow from the young man himself and, of course, the accompanying highlights best seen to be believed.

There are a few key moments where Hodgkinson leans into the matches and the book jolts to life. He intimates—always a soft touch, Hodgkinson takes no strong authorial stances—that as a phone-addicted Zoomer, Alcaraz plays “TikTok Tennis,” intentionally pulling off moves for the reels. It’s a concept my old, atrophying brain has trouble trying to fathom, but then again, so was his still mind-bending “pause in midair and go behind the back” shot against Sinner in the 2022 US Open quarterfinals. It pops up algorithmically ad nauseam this hard-court time of year, so maybe IG ball-striking is a thing those crazy kids are up to these days. It’ll be fun to ponder over the next couple of weeks, at least.

Hodgkinson delivers enough decent anecdotes to keep things humming along. My US Open enjoyment has been raised, say, 2 percent knowing Carlitos sent Nick Kyrgios to his “CCC” (his grandfather’s credo: “cabeza, corazon, cojones”) tattoo artist Joaquin Ganga, who inked up a Pokemon mural on the entirety of the mercurial Aussie’s back.

I was tickled to learn Alcaraz was in a WhatsApp with Spaniards from a Murcia junior circuit called “Open Promesas,” and that the Alcaraz family donated 1,800 used tennis balls to his primary school to mute the metal-chairs-on-the-tile-floor screeches. It’s charming in a small-town, neighbors-helping-neighbors way, and amusing because in the book it’s treated as an incredibly magnanimous gesture and not just cleaning out the dog-ball baskets. The chapter devoted to “Happy Tennis” and Alcaraz’s beloved toothy grin is also sweet and includes this banger of a Andy Roddick podcast quote: In reference to Alcaraz smiling during three 2024 Wimbledon match points against Djokovic, the sardonic Husker said, “That’s very offensive to people like me, who played in kind of a miserable, stressed-out state most of the time.”

(One major Hodgkinson annoyance, for the second book in a row, is how he repeatedly postulates that the wealthy global megastar at the center of the book doesn’t care about the money. It’s silly on its face, but it becomes downright insulting when the author details how Alcaraz picked up a seven-figure Saudi exhibition appearance fee to play in the controversial Six Kings Slam exhibition.)

As the “other” Alcaraz book to be released just in time for the Gotham major, Being Carlos Alcaraz understands, and completes, its own assignment. Readers will get to know the hombre detrás de la sonrisa on a basic, overly fulsome level, but it’s a solid Carlitos starter kit for tennis neophytes and precocious middle schoolers alike. For those who are familiar with his story, Being Carlos Alcaraz is best enjoyed as a book to thumb through during boring US Open stretches as we all collectively hold out hope for the “Gushing in Flushing.”

Brushing? Mushing? Crushing?… All right, I hear you. Vamanos!

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

RECOMMENDED

Postcard from Adelaide ’26

ADELAIDE

Taylor Fritz Sees the Game Differently

UNITED CUP

The Price is Tight

AUSTRALIAN OPEN