Fuzzy Memories

A Q&A with Nicholas Fox Weber, author ofThe Art of Tennis.

By Patrick SauerNovember 6, 2025

Fuzzy Memories

A Q&A with Nicholas Fox Weber, author of The Art of Tennis.

By Patrick J. SauerNovember 6, 2025

If asked to describe the ideal of tennis artistry, most fans would pull from a familiar canon: the angled dead-on-arrival drop shot, a feathery one-hand backhand slice, a down-the-line buggy whip forehand, a leaping at-the-apex overhead smash, a perfectly placed just-inside-the-baseline lob, or perhaps the Serena Special, a walk-off ace-up-the-tee. Outside of the underarm quick serve, there is no wrong answer—Michael Chang cramping in his ’89 French Open victory excepted—the beauty is in the eye of the match-watching beholder.

There is, however, an entirely different way of answering the question. Proper responses could include Caravaggio, William Shakespeare’s Henry V, Rene Lacoste’s alligator (er, crocodile?), Katharine Hepburn, Diego Rivera, Tom and Jerry, Babar the Elephant, Errol Flynn, or former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, all of whom warrant a sporting mention in Nicholas Fox Weber’s superb new book The Art of Tennis.

Weber, who turns 78 next month, is the acclaimed author of 15 art and architecture books and a lifetime tennis devotee who only began opining on the sport, in print, in the past decade. He’s made up for all that lost time and more in The Art of Tennis, as it’s one of the most idiosyncratic, enlightening, and enjoyable books about the inspired creativity the sport has given rise to that I’ve come across. Weber introduces a menagerie of fashionably erudite characters like Bunny Austin, the man who, at Wimbledon 1933, broke down the no-shorts barrier, and art critic Henry McBride, who had a “musical portrait” written in his honor called “Tennis” with notes and tempo listed as “point, set, match.”

Weber makes time for familiar players of the past like Bill Tilden, Helen Wills, Althea Gibson, and Guillermo Vilas, but the author goes wherever the ball bounces. There are detours to the Middle Ages, to mid-century Broadway, to present-day Africa, and to meet a few of his personal friends, including his dogged tennis partner Nick Ohly. There is a warm chapter on Ohly, who died of a massive heart attack during a midday lawn match in New Haven, Conn., one of countless rolling matches over a long friendship, moments after saying to Weber with a smile on his face: “Let’s keep going. It’s such a nice day, and the game is so much fun.”

It really is. From his apartment in Paris, Weber spoke to The Second Serve about the art—and soul—he called upon in writing his first book about the game he loves.

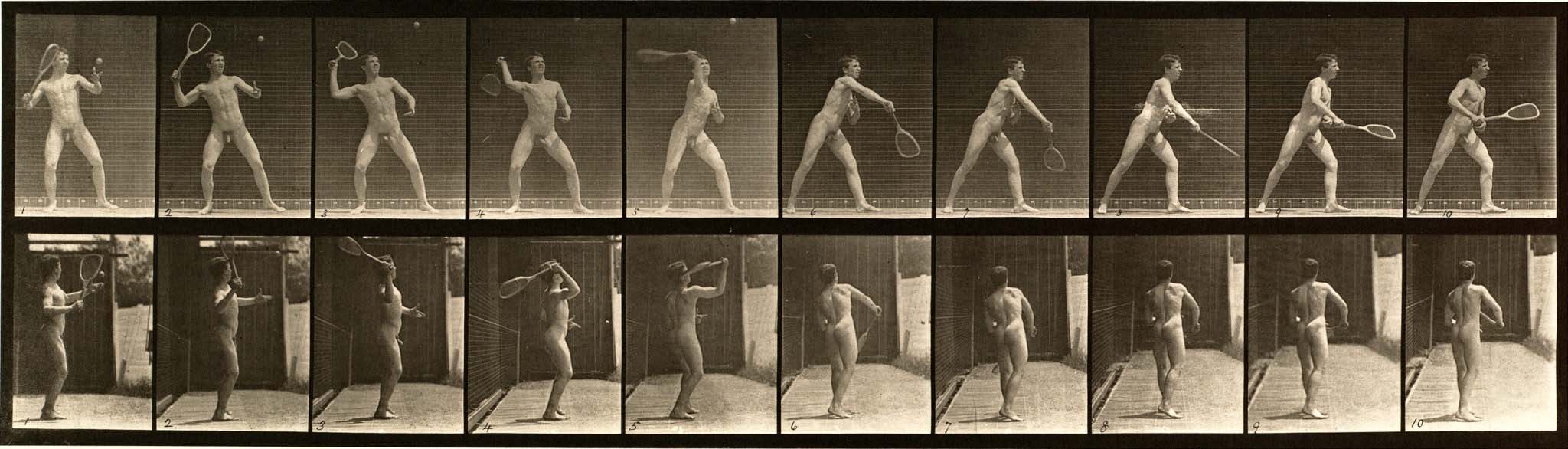

“Animal Locomotion,” Plate 294, Eadweard Muybridge

“Animal Locomotion,” Plate 294, Eadweard Muybridge

I swear this isn’t asked in jealousy, but how did you come to live in both Ireland and Paris?

In my early 20s I fell in love with a remote corner of West Cork, so in the ’80s my wife, Kathy, and I bought a small house overlooking the sea. Over the years it’s become more and more of our home. The town didn’t have anywhere to play tennis, so we built a lovely court set out in a field. It’s got fake grass, an Astroturf that survives the rain very well. It’s wonderful.

I’d been to Paris a fair bit in my life, but in 1999 I started going in earnest. I was working on a biography of the architect Le Corbusier, and we enrolled our daughter in a Parisian high school. We planned on doing one term. Twenty-five years later, it’s like neither of us ever left. We live near the Bon Marche, so I can bike to Roland-Garros. I won’t mention the ridiculous price I paid for great seats for an Alexander Zverev match at the last French Open, but seeing him at eye level was quite an experience. Most of my life is in Europe now. In the last year, I spent maybe a grand total of six weeks in Connecticut.

As far as your personal connection to tennis, have you always played, and are you any good?

As a kid I played on a public court, out there with my father teaching the Western grip. At summer camp I learned on clay, and from there I went on to full-time tennis camp. Unfortunately, I was never very good. Although at 77, I feel like I’m playing fairly well, which is not something I would’ve said at 16. In my 40s I decided to improve my French-speaking skills and my tennis as a way of handling the midlife crisis. In Paris I encountered a wonderful teaching pro from Cameroon, Pierre Otolo, and that relationship was the beginning of a marked improvement in my game.

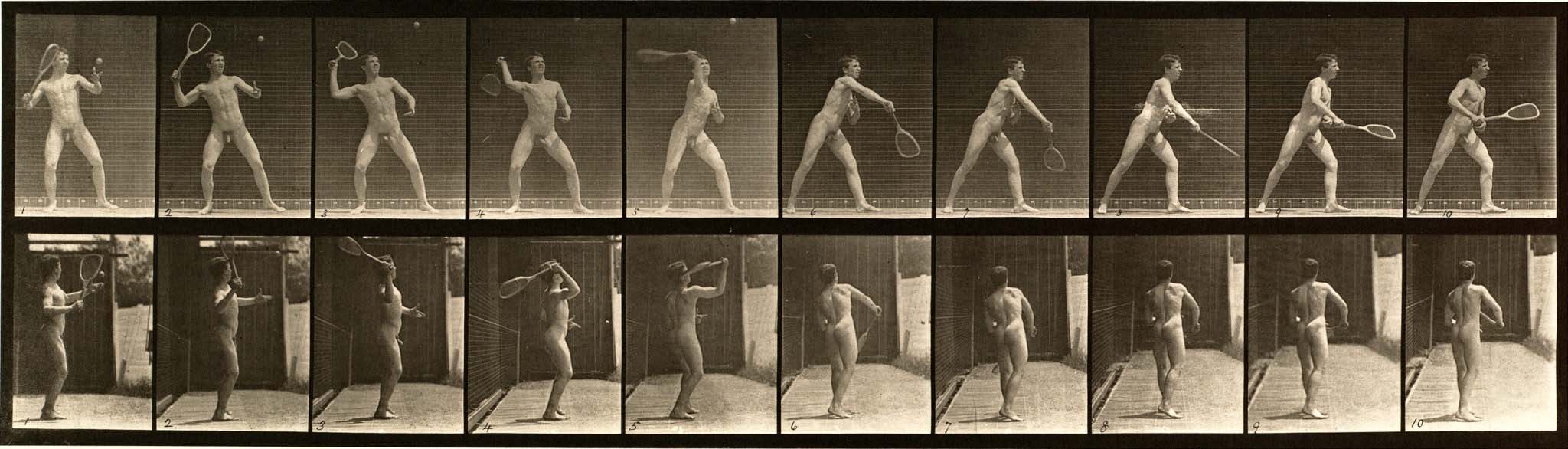

Rene Lacoste

Rene Lacoste

The title of the book is interesting because what it’s “about” is self-evident but also doesn’t capture the book’s unique spirit or structure. So, what’s your nutshell description of The Art of Tennis?

Let me back up a bit and explain how it evolved. It wasn’t even 10 years ago when I started writing for Courts magazine. It was published in French by a Belgian man who didn’t edit me. He printed and translated whatever I wrote, so I was able to follow the muse. Once I began writing tennis essays, I couldn’t stop. I became so curious about tennis-related artifacts I’d come across, like a porcelain plate in the Musée d’Orsay decorated by painter Édouard Vuillard. It was commissioned by Claude Anet, the first French national tennis champion, for his wife, with the sumptuous name Alice Nye Wetherbee. A little sleuthing revealed Anet’s given name was Jean Schopfer; his pseudonym came from a lover of French Enlightenment philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Schopfer moonlighted as an art critic, gallery owner, and author of multiple books, including a firsthand 1917 journalistic account of the Russian Revolution, and a novel director Billy Wilder later adapted as Love in the Afternoon, the 1957 movie starring Gary Cooper and Audrey Hepburn.

Fascinating guy, right? This is a long way of saying the book is about how tennis shows up in painting, sculpture, fashion, ballet, literature, etc., all the different art forms. At the same time, it’s about tennis as an art form unto itself.

The Art of Tennis isn’t structured chronologically or organized by defined sections, and each chapter works as a stand-alone, so how did you land on the through-line flow?

I can’t exactly explain it, except that one thing just sort of fell into place right after another. Now, if one chapter had a certain degree of humor or frivolity, I’d shift to one that was more serious in nature to follow, but it wasn’t a struggle piecing it together. It would be pretentious to compare my method to the way a composer composes, the way they move music in a direction that feels right, but the order of the book came along on its own.

There aren’t many descriptions of individual tennis matches or various strokes per se, but one motif you go back to multiple times is the beauty of a proper serve. What thrills you about a perfect point-starter?

It starts with the fact I’ve been trying to improve my serve since I was 8 at Tamarack Tennis Camp up in New Hampshire. Our wonderful tennis pro, Jack Kenney, said I had a “telephone booth serve,” meaning I was stuck in the tight glass enclosure and not reaching far enough in any direction. I’m not a natural athlete, so players who master the serve amaze me. Just think of the joint timing of the toss, which comes from the weaker hand, and the serving motion that requires the rest of the body. It’s amazing.

I took some lessons this summer, and the teacher actually helped improve my serve. He had great pointers on tossing the ball a bit more out of front and stepping into it the correct way. I’m serving with more consistency than I ever remember.

"Le Tennis", Charles Martin

"Le Tennis", Charles Martin

It’s good to know one is never too old to pick something new, but also that you’re still, as you put it in the book, “the intellectual who always wanted to be a jock…”

To this day, I watch a tennis match and have the complete fantasy of being on the court hitting these extraordinary shots. In reality, I’m thrilled to still be out there playing. I’ve been diagnosed with Parkinson’s.

Sorry to hear that.

Thank you. One thing those of us with Parkinson’s are supposed to do is move around a great deal and keep up our coordination. I work out with a trainer every day. Part of our routine is to play Ping-Pong and tennis. It’s my happily self-imposed treatment.

I’m glad tennis is still part of your life and equally glad you didn’t mention pickleball…

In Connecticut, I play on three public courts, two of which have been turned over. There are many advantages to living in France. One of them is that you hear very little about pickleball.

Let’s talk about some of the specific chapters, starting with “Green or Yellow?”

I run the Albers Foundation, which is dedicated to the preservation and promotion of the works of Josef and Anni Albers, the brilliant Bauhaus artists. Josef was a color theorist who devoted his life to the idea that color doesn’t exactly describe anything. If I say red, some people think of the Coca-Cola shade, others might think of LEGO. Both are correct, but neither are the same. I started to consider Josef’s notion in terms of tennis balls. The majority of people say they’re yellow, but there are plenty who swear they’re green. Which is it? How can a color be the equivalent of both a lemon and a lime? The question led me to the discovery of how tennis balls were white until 1967, when Sir David Attenborough got permission from the BBC to broadcast in color. Tennis ball colors changed because the color of the entire spectrum changed, which Josef would’ve loved. There are no absolutes when it comes to colors. Even tennis balls.

Walking down a London street a few years back, you spotted a Russian Fabergé tennis trophy in a storefront window, which upon closer inspection was awarded to the mixed-double champs at the 1912 lawn tournament in Saint Petersburg. Why was this discovery so important to you?

As a student at Columbia, I had a love for the works of Tolstoy and Turgenev, and was fascinated by the extremes of life in 19th-century Russia. I came across this fancy New York shop that carried luxurious Tsarist artifacts. I couldn’t afford a single thing in there—although for my 21st birthday my older sister bought me a medal from there, which, in Russian, is for “meritorious police service.” I treasure it and still use it as a key chain.

Anyway, I’ve always been attracted to these lavish, expensive items that have no bearing on my actual life, so I was completely taken with the elegant simplicity of the Fabergé tennis trophy. It was an aha moment as it hit me that the ones given out to champions today are ugly, unwieldy, and, worst of all, not emblematic of the sport. These ornate trophies are all over the place, which is not how you play successful tennis. The trophies should be streamlined, lean and mean. It’s possible this chapter contains a bit of envy as I don’t have a room filled with tennis trophies engraved with my name.

On that fitting Russian note, you have a chapter on Vladimir Nabokov. What about his tennis writing in Lolita rings true to you, especially given you first probably read it more than half a century ago?

This question might be better suited for psychoanalysis. Memory is a blur, but the first thing that comes to mind are the fetching young women I played tennis with as a teenager. Nabokov describes things so exquisitely, you can feel the atmosphere on the tennis court. It’s a sport that plays well for an ingenue, which he captures, but also pompous men of bluster like Humbert. I have a fondness for depictions of puffed-up, arrogant tennis types, the ones found on New Yorker covers.

This isn’t in the book, but here’s a real-life example. The Swiss actor Maximilian Schell was a collector of Josef Albers’ art and played an important role in Anni’s life. We became close friends when I wrote her biography and kept in touch. We couldn’t have been less like one another—Max was dark and handsome, I never dated Princess Soroya of Iran—so there was a bit of a rivalry thing going on. For years he’d repeat, “We should play tennis sometime,” but we never did. One morning, after an overnight flight to Munich, I met up with Max, and he decides today is the day we play a match. I’m fatigued, had gotten very little sleep, didn’t have a racquet or even any clothes. I had to wear Schell’s whites. He’s bigger than me, so I’m out there on the court barely holding my shorts up. But my competitive instincts—seasoned with a degree of rage—got ahold of me. Jet lag and all, I beat him in straight sets.

"The Death of Hyacinth", Francesco Buoneri

"The Death of Hyacinth", Francesco Buoneri

There you go. How many everyday players can say they whupped an Academy Award winner on his home court?

Guessing not many. As a claim to fame, I’ll take it.

My favorite chapter is “Anyone for Tennis,” which tracks the long, convoluted history of that particular cliché. What surprised you while digging into the phraseological bit?

I have a fuzzy recollection when I was young of someone walking into a room and, apropos of not actually heading out to the court, saying, “Tennis, anyone?” I was baffled; where did that even come from? And then, my God! One of the earliest mentions comes from a young theater actor named Humphrey Bogart? Who walked out and loudly said it to clear the stage of non-lead actors? And then in interviews over the years, Bogart allowed that yes, he was the first to say it, but also denied he ever said it all? There’s also the lingering question of whether it originated as “Tennis, anyone?” “Tennis, anybody?” or “Anyone for tennis?” The phrase’s lineage includes George Bernard Shaw, Somerset Maugham, Bob Hope, Eric Clapton, and Monty Python. The idea that this goofy enduring expression—which, in Billy Wilder’s 1954 film Sabrina, represented not the actual sport but, as I say in the book, “a happy-go-lucky pleasure-seeking rich boy”—contains truth, a lack thereof, and something in between has long intrigued me.

I’m fairly certain I first heard “Tennis, anyone?” in a Looney Tunes cartoon…

Apparently, after the first time my wife, Kathy, took me home to meet my future mother-in-law, she said to her daughter, “Well, I didn’t expect Bugs Bunny.” The night before our wedding, I didn’t sleep well. The day of, I had all sorts of nervous energy, and I knew the judge was a tennis player. We played three sets before the ceremony. Next year, Kathy and I celebrate our 50th anniversary.

It’s not in The Art of Tennis, but given the book’s nature, I’m wondering, what did you think of Challengers?

I’ve rarely been so ambivalent about a movie in my entire life. I know the director, Luca Guadagnino, we were supposed to work on a film about the Alberses together. I was totally biased in favor of Challengers, but it is just so extreme. There are moments where I just don’t know what to make of it, except to say it’s got a lot of energy.

Lastly, can you please tell me how your Senegalese nonprofit came to be and what part tennis plays in it?

Early on in Paris, I needed to go to a dermatologist, but it felt like an invasion of my teenage daughter’s space to go see hers. I opened the yellow pages and found a doctor named Gilles Degois. It doesn’t get more French than that, so I figured it would be a chance to practice my language skills. He picked up my American accent right away and said a sentence to me, in French, that ended with President Bush. We began to talk about world affairs. He told me he helped run a small charity where doctors went to eastern Senegal four times a year to provide medical care and to continue building a facility. I’m not sure what came over me, but I looked at Dr. Degois and said, “I’d like to go with you.” Knowing these doctors were spending their own money and vacation time to go to an extremely underprivileged part of the world proved life-changing.

Unlike American charities, they run on a shoestring budget. Initially, I simply helped raise U.S. funds. Later, I started a very modest support group to build another medical center in a different rural locale. There was no facility for miles around, so people relied on local cures and inadequate medicine. It took off, one thing led to another, and eventually we built a kindergarten, maternity and pediatric wards, and we’re now working on a small museum. I’ve never been able to comprehend why some of us are lucky enough to be born into fortunate circumstances and others aren’t. I’m not from an aristocratic family or anything, but I certainly got to play tennis growing up, so why shouldn’t other kids? Tennis is how my instructor and friend Pierre Otolo was able to provide for his family. Pierre was born into poverty, but he crossed paths with Yannick Noah’s father, who ran a junior team of Black players that opened up a world of opportunities. Pierre frequently returns to Cameroon, using tennis as a springboard to impact hundreds of lives in positive ways. He’s served as another inspiration to me.

About a dozen years ago, we built a court in the village of Sinthian. Incredibly, it’s become a gathering place where we provide medical care and supplies, and hold all types of recreational activities. I believe everyone should get the chance to play tennis. It’s one of the joys of life, and nobody had ever played before. In Senegal, the first person I played with was the young man who drives me everywhere. Those roads are too tough for me to navigate. One morning, he drove me to the courts. I asked him if he wanted to join me on the court. He’d never held a racquet, so the first thing I did was show him how, just like I was taught all those years ago.

Every time I visit Senegal, we play tennis.

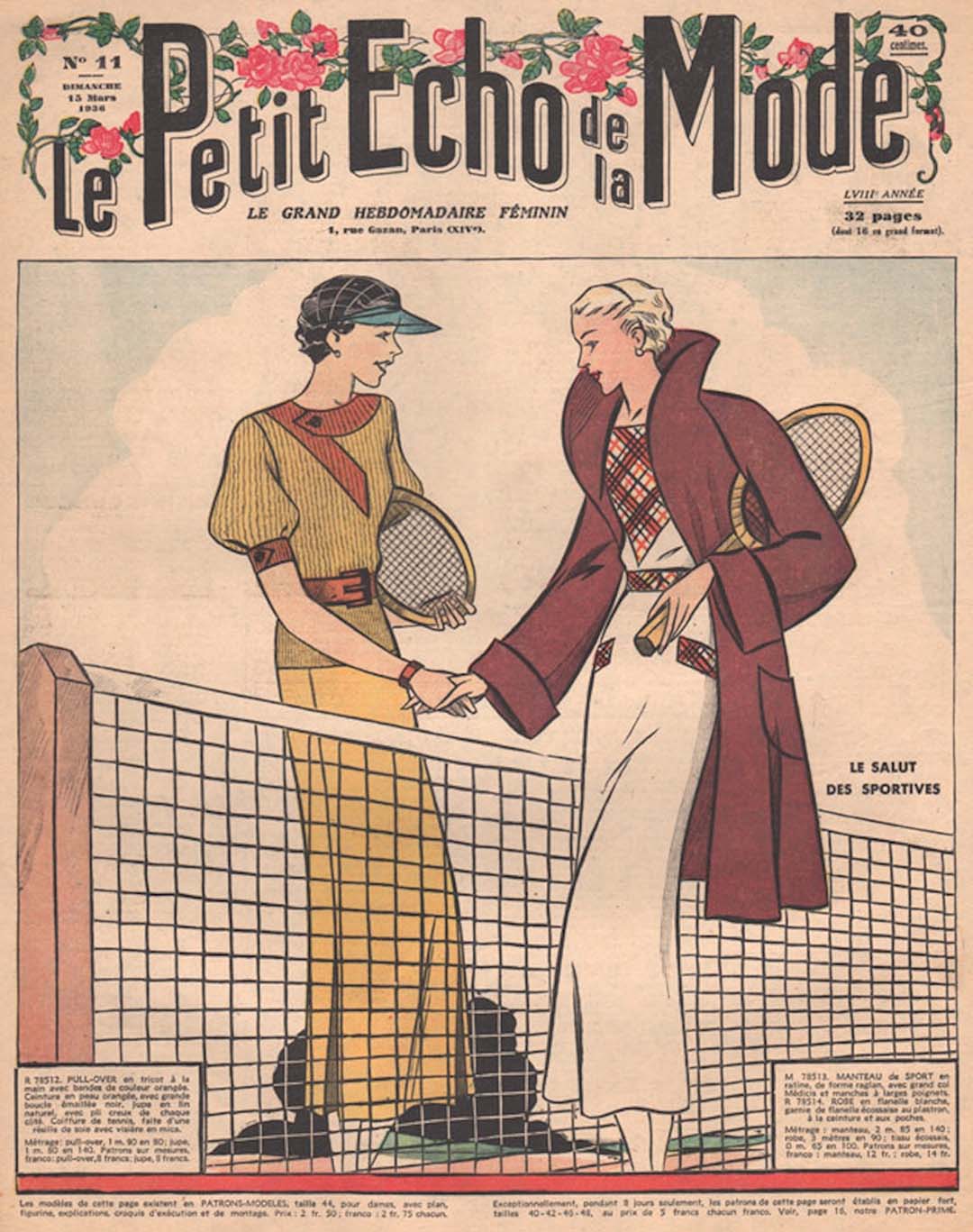

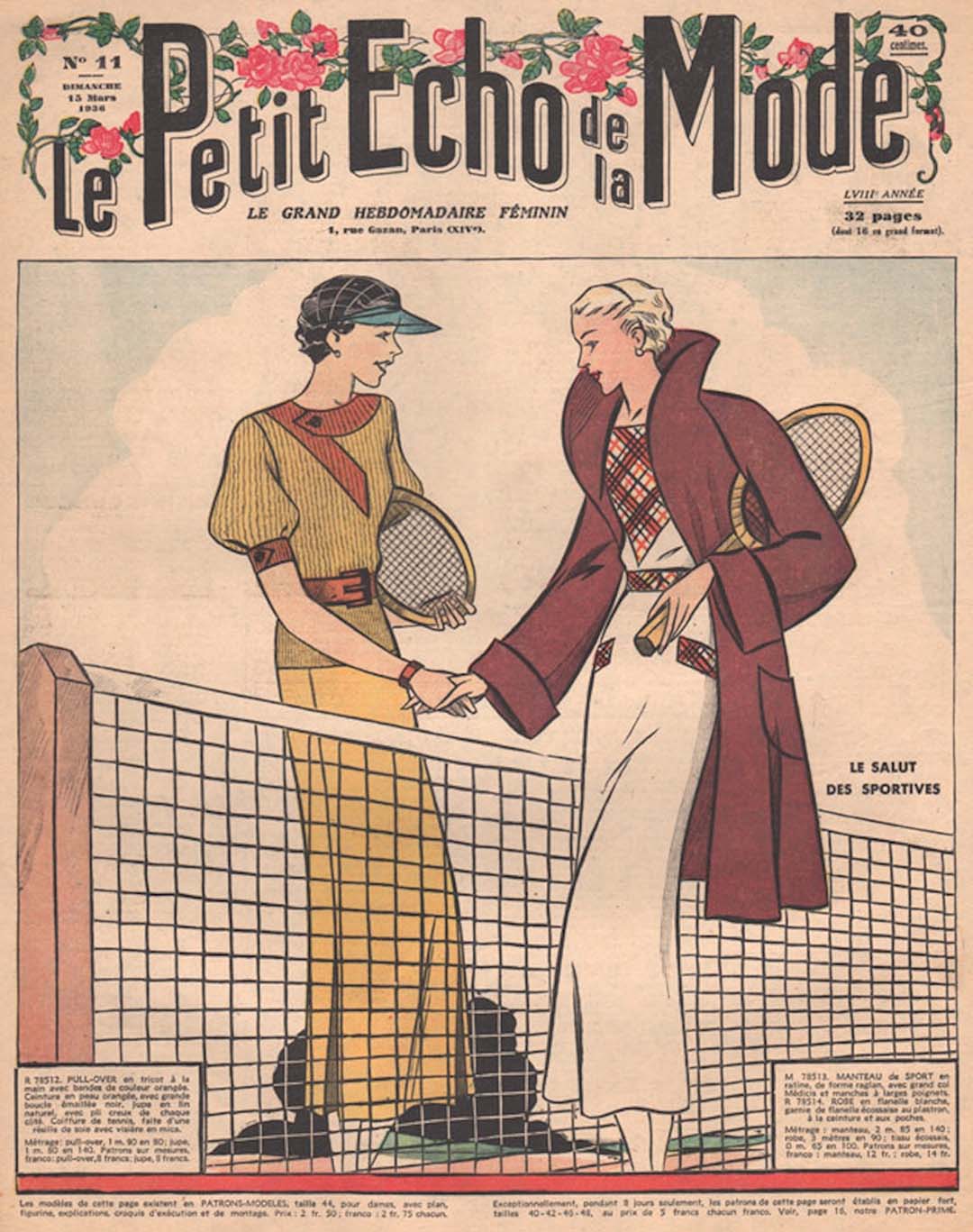

Le Petit Echo de la Mode, 1936

Le Petit Echo de la Mode, 1936

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

RECOMMENDED

Big House Boris

BOOK REVIEWS

New Again: Adidas’s Barricade Gets An Update

SNEAKERS — WILSON