Coco's Hits the Ceiling

Coco's Hits the Ceiling

The coaching carousel spins.

The coaching carousel spins.

By Giri NathanSeptember 20, 2024

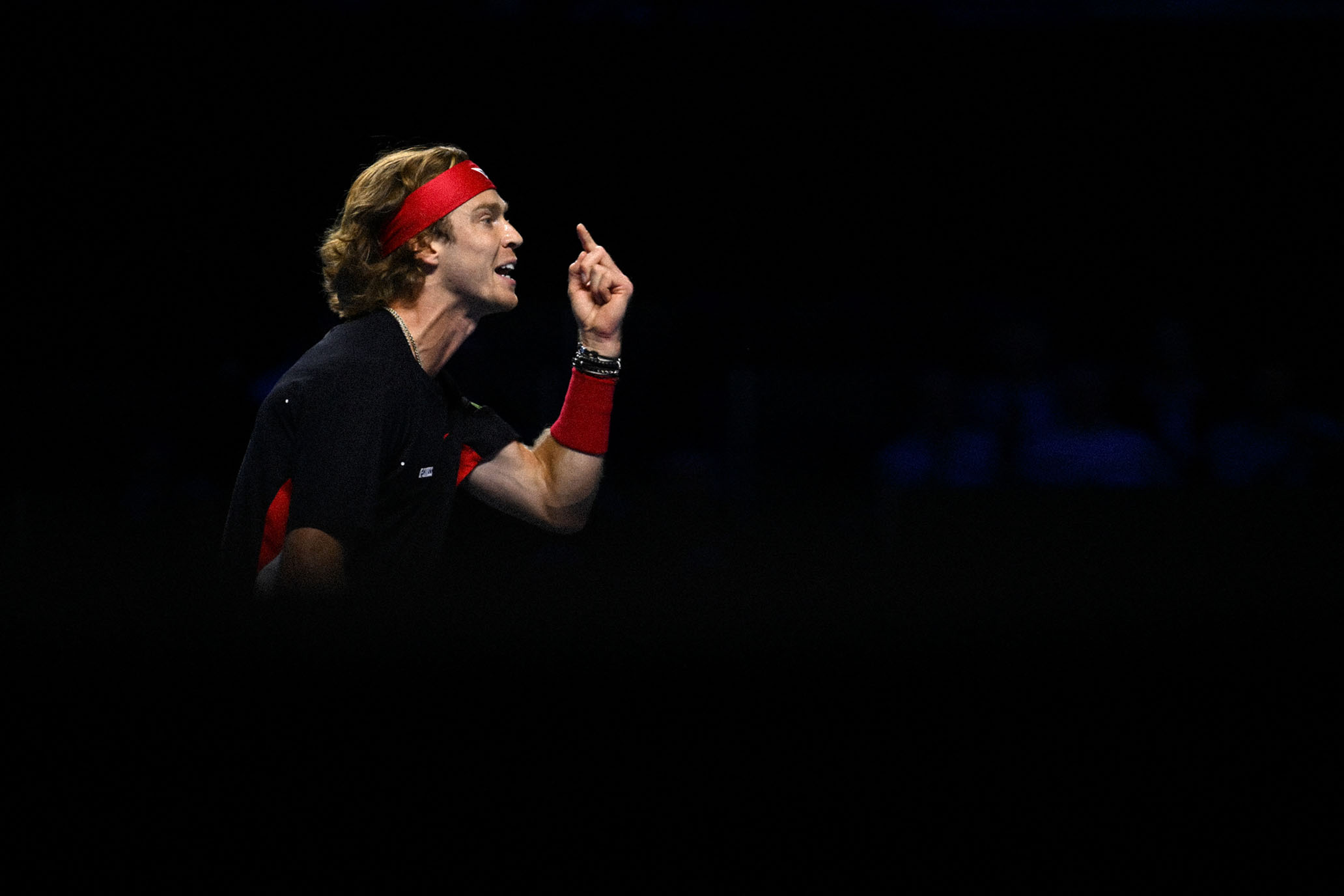

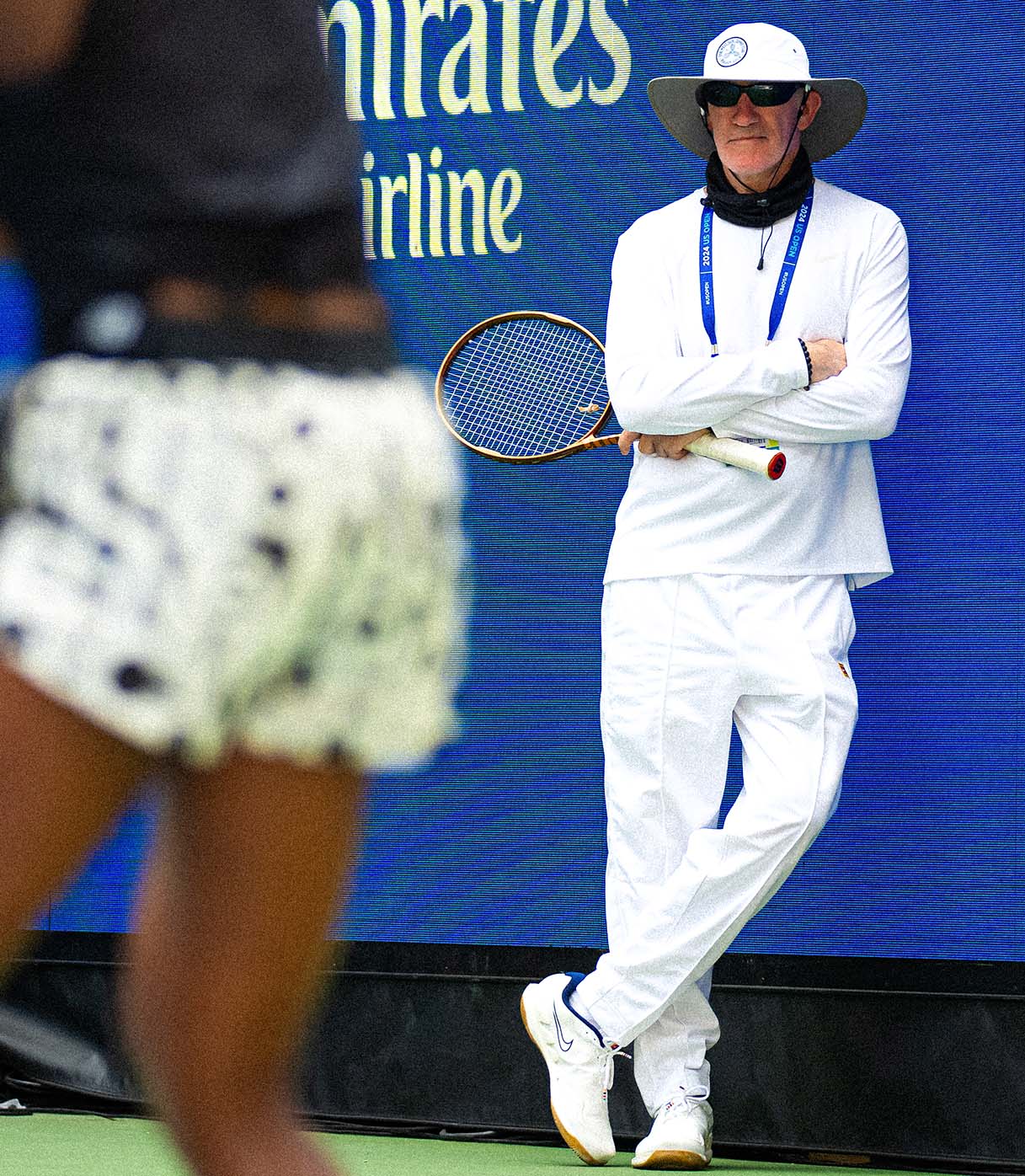

Brad Gilbert takes in Coco Gauff’s serve at the US Open this year. // Getty

Brad Gilbert takes in Coco Gauff’s serve at the US Open this year. // Getty

The more I think about the 2023 US Open women’s final, the stranger that result looks. Aryna Sabalenka losing a hard-court Slam final after going up a set and a break? Unthinkable. Now Sabalenka is the ruler of the hard-court Slams, finaling in the last four and winning three of them. This was the only one she lost. It’s partially because Sabalenka’s game cracked under the pressure of a nasty New York crowd, but it’s also because of the player that crowd was supporting: Coco Gauff, 19 years old and in the middle of the most fruitful stretch of her career.

That was a transformative summer for Gauff. She’d flamed out of Wimbledon after a tough draw of Sofia Kenin in the first round, then, per her dad’s urging, hired Brad Gilbert as coach. The collaboration immediately bore fruit. Gauff won titles in Washington and Cincinnati, and after clambering back into that US Open final with some of the most persistent defense I’ve ever seen, won that, too. In that summer hard-court season she won 17 of 18 matches, culminating in her first major title. She also got what is still her only win over the world’s best player, Iga Swiatek. (She’s lost the other 11 matches.)

Whatever Brad Gilbert, voluble ESPN analyst and sporadic coach to the stars, brought to the team was clearly working. The technical flaws in Gauff’s game were still there, on the serve and forehand, but they didn’t seem to be barring her from victory. Gilbert is arguably most famous for the art of winning with a flawed foundation. And something about Gilbert’s relaxed manner was speaking to Gauff: “The way that he says it. Sometimes it’s not always about the message. I don’t think the message has changed for me, it’s more about how the message was relayed to me,” she said in press at the Open. Months later, in an interview, Gilbert explained his thinking about Gauff at the start of their collaboration. He didn’t think that the wonky forehand, source of so much ire from Gauff observers, was actually that big of a deal. Mostly he wanted to steer her away from offense and toward a more defensive style that tapped into her phenomenal movement—her one true outlier skill on a tennis court, as I see it.

Gauff’s career in the year since that US Open win evokes a specific image in my mind: hitting a ceiling, quite hard, and ending up with a bit of a bruise. She rose to a career-high ranking of No. 2 this season. But all the while, peers like Swiatek and Sabalenka were ascending to a level of tennis that Gauff cannot yet match. It isn’t only a handful of elite players causing her woe, either. This season, Gauff has gone 4–8 against top 20 players, and just 17–15 against top 50 players.

Compared with last summer, this summer left her cold. She had a disappointing showing at the Olympics, where she competed in the singles, doubles, and mixed and took no medal. At Wimbledon and the US Open, she made decent runs, ended both times by Emma Navarro, a countrywoman on the rise, with less buzz but fewer holes in her game. In their first meeting at Wimbledon, Gauff visibly pleaded with her box for advice, and afterward she said, “I felt like I wanted more direction.” In their second meeting, Gauff hit 19 double faults, 11 of them in the third set of the match. Afterward she described how she sometimes drops the left side of her body during her serve, a tendency she’s aware of but struggles to control amid the nerves of a match.

The foundational issues that Gauff had managed to mitigate for stretches of her career came roaring back into prominence. If she’s to keep up with the best players of her era, they’ll still need fixing—but that’ll be someone else’s job. Gilbert, in his strange dual capacity as coach and analyst, was thrown on ESPN immediately after the US Open loss to Navarro, as if to account for it, and he took a bit of a beating on the air. Of course, it is not Gilbert who went out there and hit 60 unforced errors, but it is his job to put her in a mindset where she does not hit 60 unforced errors. It’s easy to say in hindsight, but to anyone who’d been watching closely, it was clear that their collaboration was in its waning days. The body language was already strained by Wimbledon and soured further at the US Open. Gilbert announced the inevitable on Wednesday, thanking the player and the team for their 14 months together and wishing her luck.

From the outside, it’s always hard to grasp precisely why a player cans a coach, but if I were to take the average of the various explanations that players have given over the years, it’s something like this: The brain stops responding to a particular type of motivation. The tips and exhortations recede into background noise. A new voice is needed. Brad Gilbert has…let’s call it an idiosyncratically peppy and chatty style of motivation, which may well have a built-in expiration date for most consumers. Even in the golden days, during the US Open run, there was a moment where Gauff snapped at him from court: “Stop talking.” Now it’s up to her to decide who’s going to start talking next. She could pick up Wim Fissette, who oversaw some of Naomi Osaka’s biggest successes and was also fired this week; Osaka has since been seen with Patrick Mouratoglou, in what strikes me as an extremely unintuitive pairing of student and teacher. The coaching carousel spins on and on and on.

The Hopper

—CLAY Tennis on Beatriz Haddad Maia’s US Open run.

—Giri on Iga Swiatek’s loss to Jess Pegula.

—Jon Wertheim’s mailbag is full this week.

—Sara Errani and Andrea Vavasori have won the US Open mixed doubles.

—Tim Newcomb on Taylor Fritz and Asics.