Bjorn Free

Bjorn Free

Book Review: Heartbeats: A Memoir, by Bjorn Borg.

Book Review: Heartbeats: A Memoir, by Bjorn Borg.

By Joel DruckerSeptember 19, 2025

In the literature department I’ve occupied in my mind since the summer I started playing tennis more than 50 years ago, there is a course titled Tennis Belles Lettres that explores the autobiographies of tennis legends. Billie Jean King crafted a tale of destiny. Jimmy Connors took on the world. Andre Agassi dissected his love-hate relationship with tennis. John McEnroe dissected his love-hate relationship with himself.

What should we expect from Heartbeats, Bjorn Borg’s new autobiography (as told to his wife, Patricia Borg)? While the four tennis legends listed above have issued ample public comments for decades, Borg has been exceptionally silent. “For me,” he writes, “standing in front of cameras and talking at press conferences was torture.” As anticipated, a request to interview him for this story was declined.

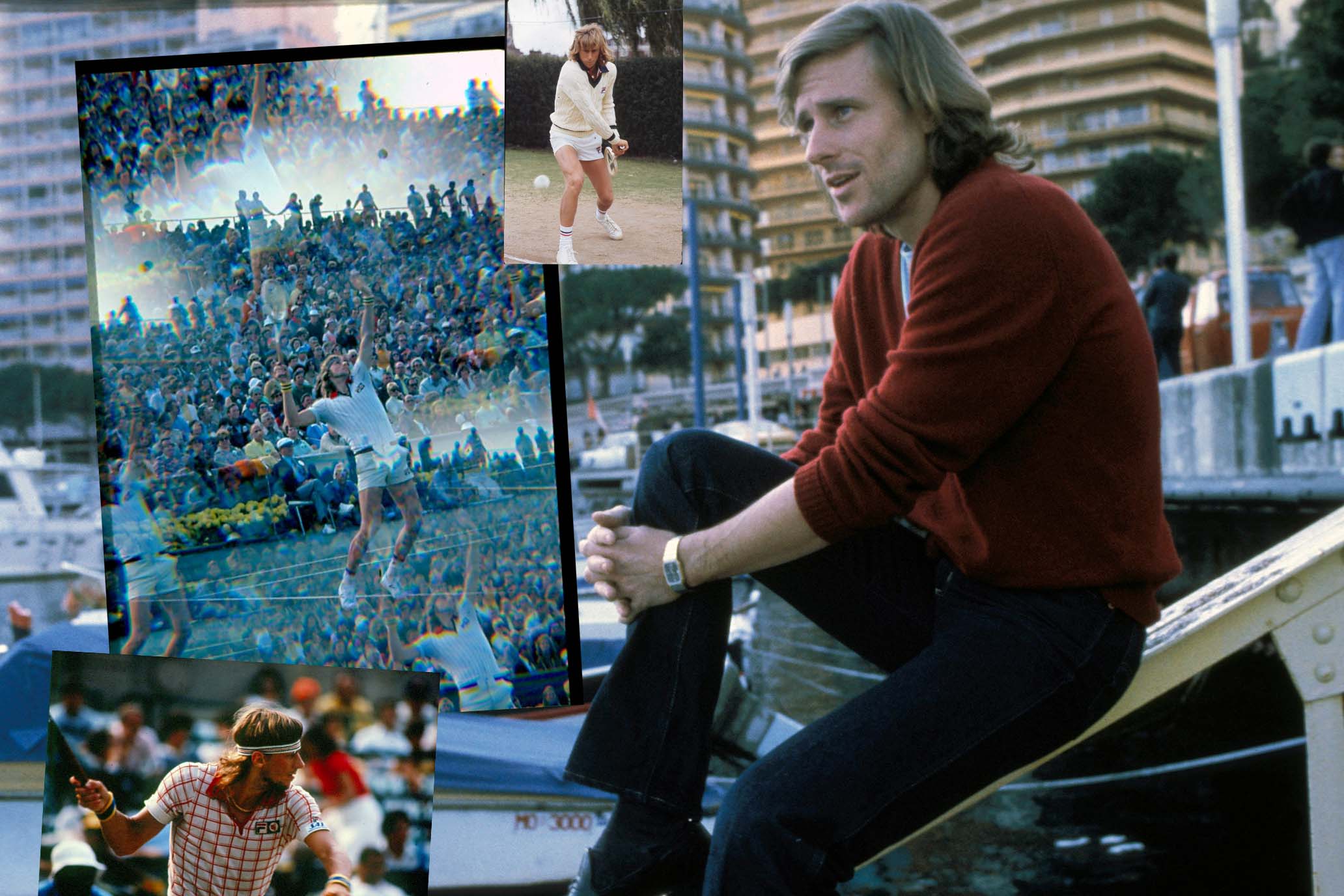

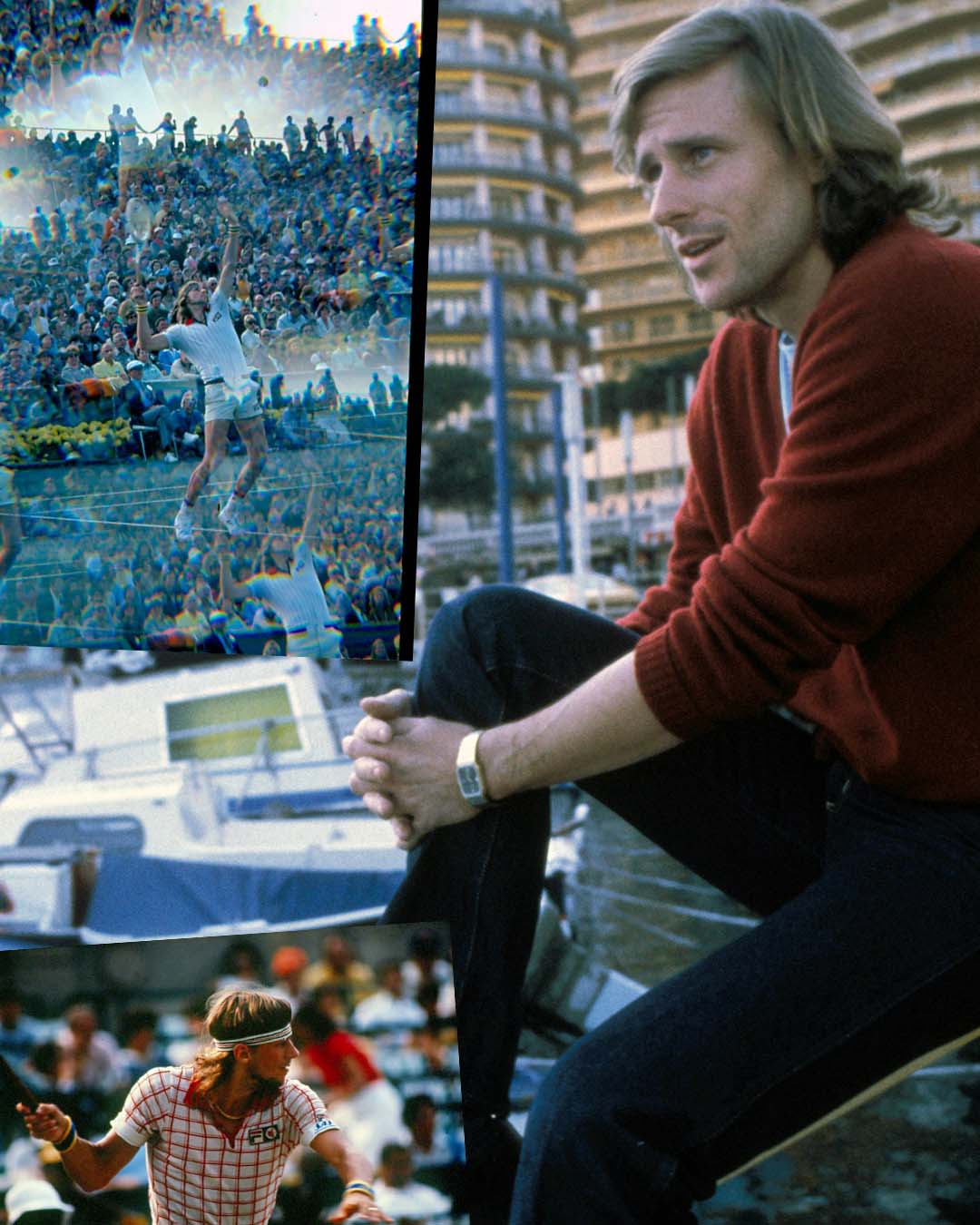

Nicknamed the Ice Man for his unflappable behavior in the heat of battle, Borg’s exceptional reticence—particularly when juxtaposed against the heat generated by his primary rivals, McEnroe and Connors—only added to the aura he’d long built as tennis’ quintessential cool pop icon. In 1973, the month he turned 17, Borg burst onto the scene with a quarterfinal run at Wimbledon, triggering what was dubbed Borgmania. The Swede with the long blond hair and swimmer-like body emerged as a one-man version of the Beatles, in London that debut year and for the duration of his days at the All England Club escorted by a cordon of British policemen shielding him from teenyboppers and paparazzi, evoking memories of A Hard Day’s Night. First alongside Connors, later with McEnroe, accompanied by poet-musician Guillermo Vilas and disco-era darling Vitas Gerulaitis, Borg by the end of the ’70s had emerged as the lead attraction in tennis’ transition into the rock ’n’ roll era. Prior greats were crooners. These men were electric.

Given Borg’s on-court achievements and crossover popularity, it would have been easy for him to craft a book filled with mild commentary about notable matches and a smattering of the celebrity-laced tales that invariably accompany the journey of a highly accomplished athlete who, once retired from competition, spends the balance of his or her life as the custodian of an image. Should you only seek those, rest assured: Places like the ’70s hot spot Studio 54 and the All England Club each receive appropriate measures of coverage.

“I sat there wondering what had gone wrong,” Borg writes about his state of mind after the 1980 Wimbledon final versus McEnroe had gone into a fifth set despite the Swede holding seven championship points. “John, meanwhile, was fired up, like the young rebel he was.” But as McEnroe would say, let’s face it: A few clicks on YouTube to see the actual match—most notably, its 34-point fourth-set tiebreaker—more eloquently display what proved to be Borg’s fifth straight Wimbledon title run. As I’ve learned firsthand from covering tennis for more than 40 years, the participants speak best with their racquets.

But to his credit, Borg digs into other areas, calling himself out repeatedly for character flaws and regrettable occurrences. “I was so used to being the centre of attention and having someone look after me, ever since I was a kid,” he writes. “If no one was watching, I could go completely off the rails.”

Addressing his long-rumored penchant for substance abuse, Borg writes, “To this day, I’m ashamed just thinking about it. That was the worst shame of all, that my drug problem had reached such a level, with such serious consequences, and all in front of my own father. I didn’t even ask the doctors or nurses how close I’d come to dying. I didn’t want to know.”

Along with this come accounts of failed romances, death threats, and, most recently, an aggressive form of prostate cancer. As Borg describes yet another unenjoyable off-court moment, “The doctors said I would have died if I hadn’t had the surgery. Maybe I had fooled myself into thinking I had a choice.”

Most endearing is the high regard Borg shares for two men, both of whom died in 2008. One is his father, Rune: “Dad was the rock of the family.” The other is his longstanding coach Lennert “Labbe” Bergelin: “Labbe’s huge heart was dedicated to tennis, and he was fantastic with us juniors.” Borg eventually hired Bergelin to become tennis’ first full-time traveling coach.

Here we tap into Borg’s legacy. So subdued is Borg that it’s easy to forget that he was a tennis revolutionary. In addition to the new step of having a handler in Bergelin, Borg was the first player who made significant topspin the essential part of his arsenal. While others such as Lew Hoad, Rod Laver, and Manuel Santana were able to hit many a topspin drive, they’d done so mostly as a supplement to flatter strokes and extensive all-court play. But Borg was primarily a baseliner, his whipped and dipped ground strokes literally altering the trajectory of where the ball went, how points were built, and the whole matter of contact point management. From what Borg commenced, follow the high-bouncing line to such greats as Vilas, Ivan Lendl, Andre Agassi, Rafael Nadal, Novak Djokovic, and Jannik Sinner. Borg literally changed the shape of tennis.

But did Borg’s making prove his undoing? From the obsessive training rituals he and Bergelin adhered to like monks to a shrine, to the narrowness of his attrition-based playing style, to the carousel-like itinerary of tournaments and lucrative exhibitions that blossomed during tennis’ new Technicolor era, it appears that all the ingredients were in place for Borg to grow anxious and world-weary. Describing life in 1980, in the midst of a three-year run when he would dazzle the world with victories at Roland-Garros and Wimbledon, Borg writes that, “despite how well everything was going, I started to feel a creeping sense of panic…. The only time I got any real quiet was in my hotel room, and even that had started to feel more and more like a prison.”

A fatigued Borg took off the 1982 tennis year. The public premise was that he would compete again in ’83. The metaphoric movie trailers for Borg’s return were a series of exhibitions he played throughout ’82. I covered several of those, and the anticipation of Borg back in the mix ran high. But Borg has now issued a confession. Appearing on Johnny Carson’s late-night TV show in July ’82 two days before playing Connors, he writes that, “I talked about having many more years of tennis ahead of me. Of course, none of that was true.”

So it came to be that in January 1983, Borg announced his retirement. Over the next couple of years, he’d play a few more matches, mostly out of obligation. There’d also be a brief return to the tour in the early ’90s, Borg by then unable to compete with his prior effectiveness. Later came fun and games on the emeritus circuit more formally known as tennis’ senior tour.

The result is that a spirit of sadness pervades this book. If life has done well by Borg, tennis has been a mixed bag. He in large part was the sport’s first burnout case, setting the foundation for the likes of McEnroe and Agassi to eventually write books that thoughtfully explored the sport’s toxic qualities. This stream of literature was different from prior tennis books. Tales such as Arthur Ashe’s 1975 work Portrait in Motion and Gordon Forbes’ 1978 work A Handful of Summers depicted the traveling circus as a group of merry marauders, happy to be adults playing a game.

As for Borg, by the end of 1981, a darn good year considering he’d beaten Lendl in a five-set Roland-Garros final and only lost the Wimbledon and U.S. Open finals to an inspired McEnroe, at all of 25 years old, the carefree Beatle had given way to the jaded, late-stage Elvis: caught in a trap. “I was let out to play my matches,” writes Borg, “expected to perform, then locked back in again.” But the prison also made him rich. In that fantasized literature class, what would the professor teaching this book make of the gain-pain ratio between Borg’s youthful dreams, accumulation of wealth, and adult nightmares he appears to have at last recovered from?

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

RECOMMENDED

Big House Boris

BOOK REVIEWS

New Again: Adidas’s Barricade Gets An Update

SNEAKERS — WILSON