A Forensics of the Foro Italico

A Forensics of the Foro Italico

The architects and artists who built the Fascist sports complex sought parallels with previous Roman empires.

The architects and artists who built the Fascist sports complex sought parallels with previous Roman empires.

Gerald MarzoratiMay 9, 2024

A Forensics of the Foro Italico

A Forensics of theForo Italico

The architects and artists who built the Fascist sports complex sought parallels with previous Roman empires.

The architects and artists who built the Fascist sports complex sought parallels with previous Roman empires.

Gerald MarzoratiMay 9, 2024

I.

The Fascist Academy of Physical Education was founded in Rome in 1928. Its mission, at once pointed and sweeping, was to help create for Italy what the world’s first Fascists called the New Man. This New Man was to be modern, virile, confident, unquestioning, forceful, and, when called upon by the state—by its dictator, Benito Mussolini, Il Duce—ruthlessly violent. Sports would play a significant role in shaping the New Man. The Academy’s essential aim was to train physical-education teachers for Italian schools and, more important, sports instructors for the Opera Nazionale Balilla (ONB), a network of youth organizations that would be developed into a compulsory paramilitary comprising millions of fit and indoctrinated boys (and girls, eventually), parading in Italian towns with scaled-down service rifles and prepared (or so they believed) for battle wherever.

A new home was built for the Academy in 1932, along the River Tiber north of Rome’s centro storico, at the base of Monte Mario. Four years later, behind the Academy, a monumental statue of a Balilla boy, chiseled in an appropriated, exaggerated classical style, was solemnly unveiled to mark the 10th anniversary of the ONB. It remains astonishing today in both its scale and detail. Atop a hefty pedestal, and hewn from white marble, the young paramilitary rises nearly three stories. His ONB uniform—T-shirt and shorts—clings tightly to his muscular frame. His face reveals nothing but purposeful concentration. He shoulders a rifle, and from his neck onto his expansive chest dangles a pack exposing a gas mask—a timely touch. In 1936, the Italian military was in the thick of its fight to seize Ethiopia, an imperial conquest that relied to no small degree on aerial bombardments of mustard gas.

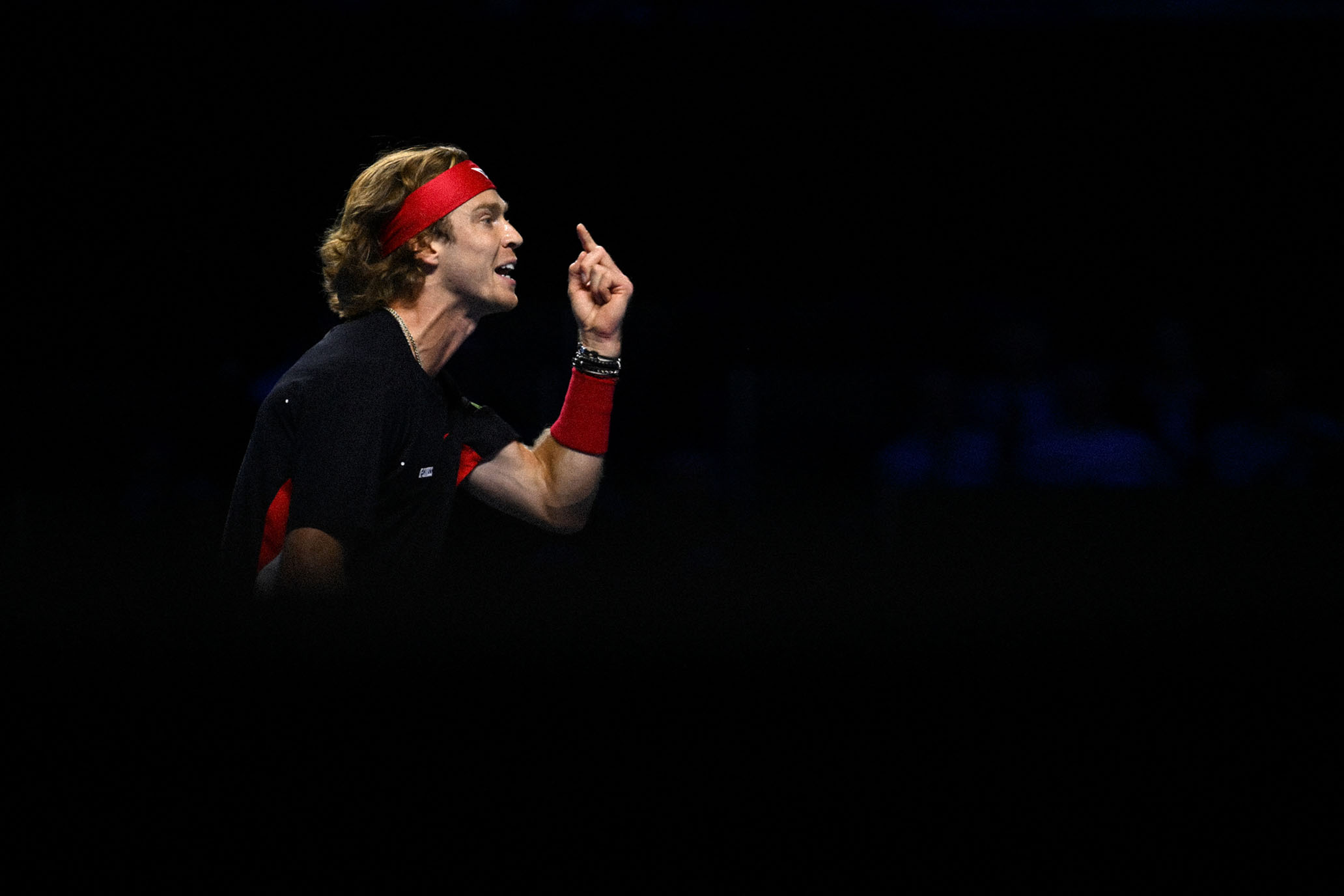

I found myself gazing up at the face of this towering figure one overcast morning last May. It is a face its sculptor had rendered a little older than that of a teenage boy; better, perhaps, to convey that he was already a young New Man, his molding complete: physically developed, disciplined, ready for action. He looked, I couldn’t help but think, about the age of Casper Ruud, who I was watching as he struck one inside-out forehand after another during a practice session on Court 8 on the grounds of the Italian Open, which was about to enter its first weekend. The statue of the OMB paramilitary loomed above Court 8, along the central walkway of the tournament, the grounds of which are situated on the southern end of the sprawling sports complex known as the Foro Italico.

At what is now called the the Foro Italico, a statue of a “Balilla boy”, was unveiled in 1936 to mark the 10th anniversary of the Opera Nazionale Balilla, a network of youth organizations that would be developed into a compulsory paramilitary. // Alamy

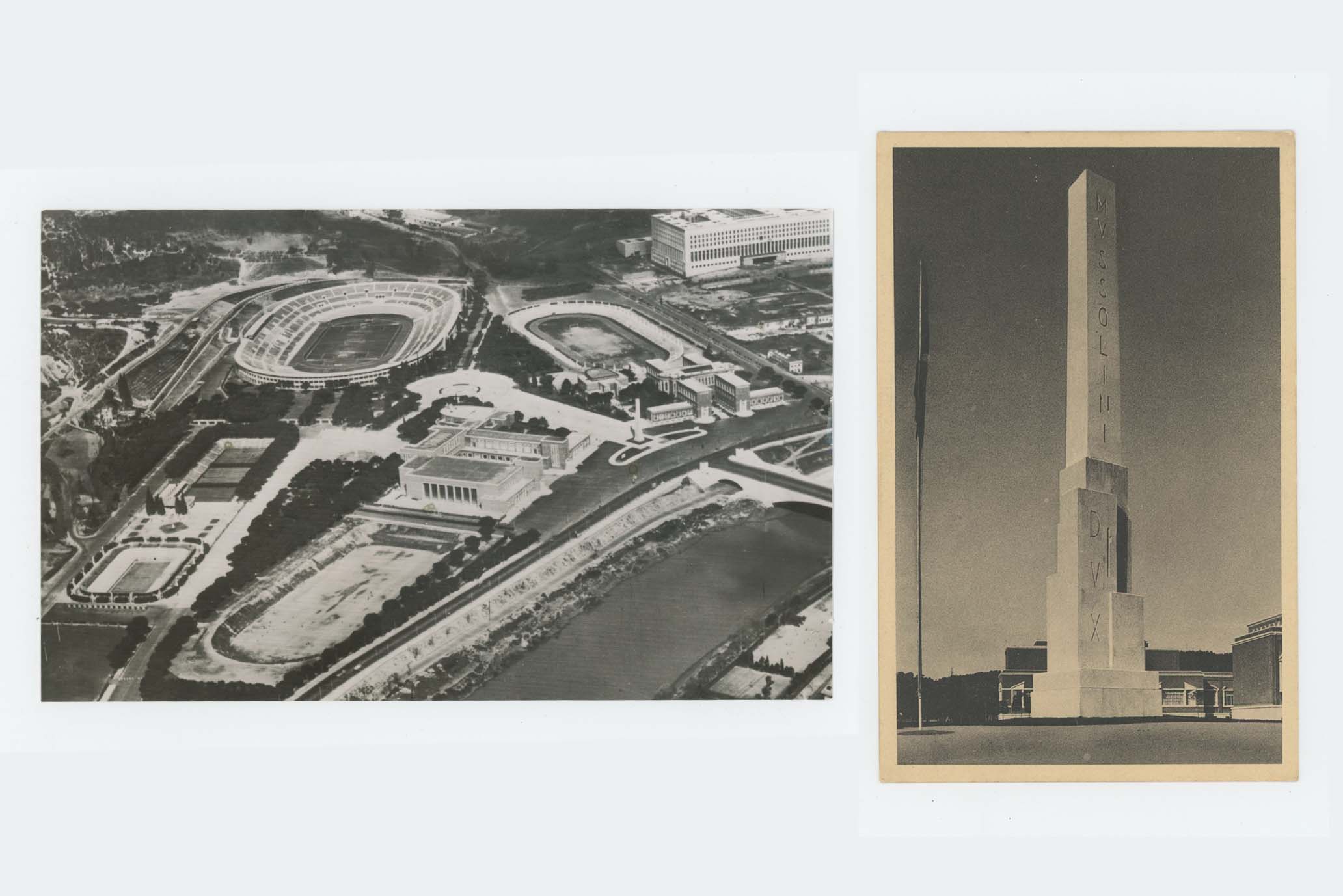

The Foro Italico had originally been designed and constructed as the Foro Mussolini. Plans for it were drawn up, under the direction of a then-prominent architect named Enrico Del Debbio, beginning in 1928, three years after Mussolini declared himself dictator. The Foro was to be a complex of buildings and stadia, parade grounds and piazzas. It was to manifest artistically and architecturally Il Duce’s promotion of the idea that the Fascist police state he was forging was, among other things, an ambitious 20th-century revival of Rome’s past. Caesar Augustus had had a forum, and he would have one too—a grand public space for military ceremonies, commemorations, processions, sporting events, and more. Mussolini’s pursuit of romanitá—a caricatural notion of ancient Roman-ness, meant to manifest Fascist conceptions of unity, control, and heroic destiny—was impassioned and near boundless. He introduced the so-called Roman salute of the stiffly raised right arm (though it’s unclear whether ancients Romans ever employed it) and had his proclamations published in Latin. A forum bearing his name would at once align him with Rome’s past grandeur, pronounce that he was the state, and leave a sprawling legacy of marble and tile, greenswards and concrete, for a future that would glorify him and his reign.

It didn’t work out that way: He wound up shot by partisans in the last days of World War II, his Fascism routed, his Italy decimated, his body hung by its feet from a metal girder at a half-built service station in Milan. But the Foro survived. Rome had been bombed, but not the Foro. Two weeks after the liberation of Rome, in June of 1944, it was transformed into a U.S. Army rest center. Bill Hargis, who’d coached football and track at Kansas University in the 1930s, was at the rest center as an armed-forces athletic consultant, and he composed a little guide to the Foro for the American soldiers encamped there. “When you walk over to the P.X., look at the statue of the ‘Balilla,’” he wrote. “The marble figure of a boy with a gun and gas mask gives you a fair idea of what Mussolini was training Italian youth for.”

Who attending the Italian Open today gives a thought to the statue of the Balilla boy—to what it was meant to honor? The Foro is filled with creations designed to evoke Mussolini’s greatness and imperial ambitions. Who, wandering the Foro, has a sense of that? The architects and artists who built the Foro had worked to revive the past, adopt and adapt it, construct parallels with previous Roman empires, grandly convey ultranationalist order and power: Fascist ideals. Who, today, understands the Foro that way? What, over time, has it all come to mean—if, now, it means much of anything at all?

"Canadian Doubles." / MGM Studios

"Canadian Doubles." / MGM Studios

II.

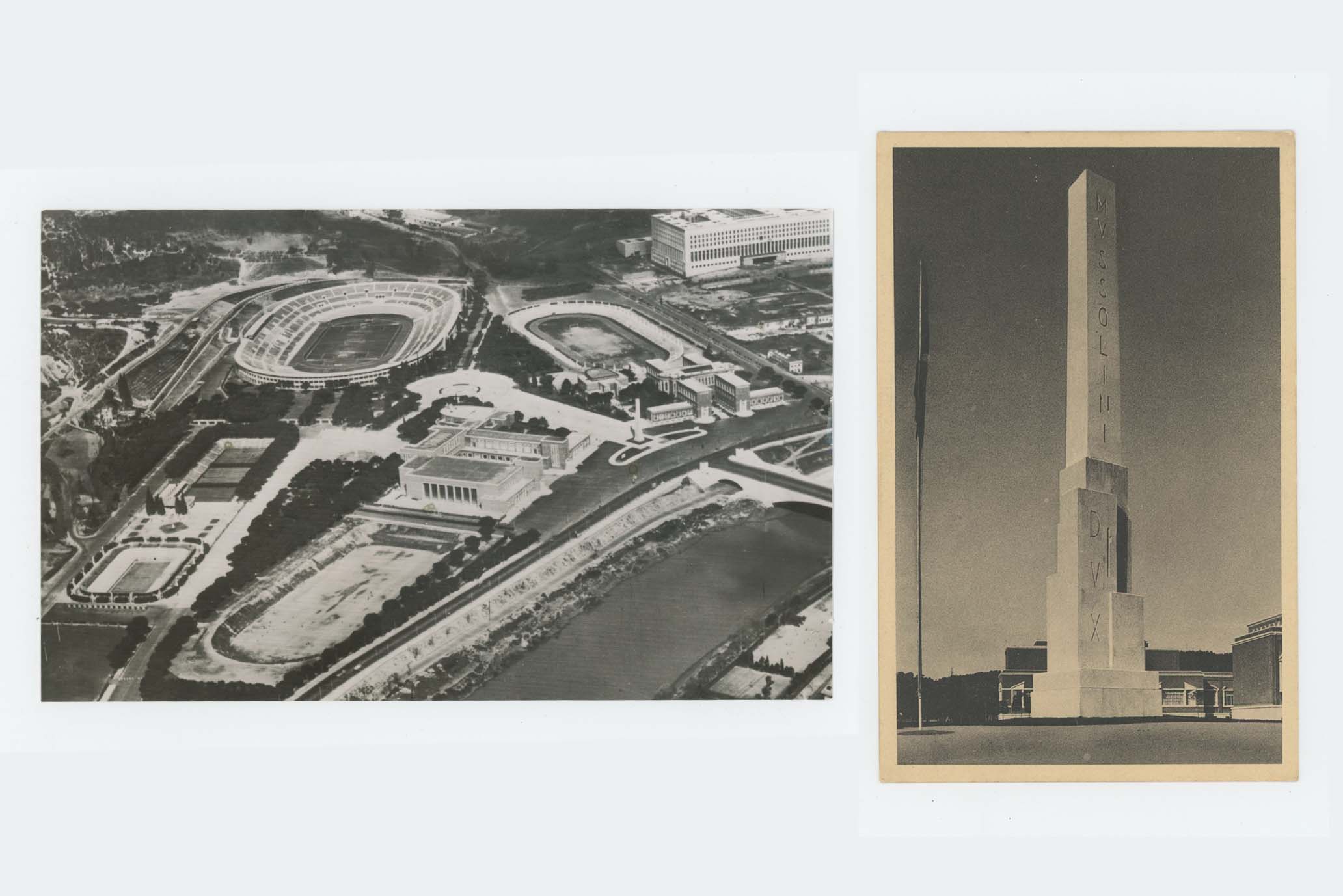

Enter the Foro Italico at its northern end, from the roadway that curves along the western bank of the Tiber, and you’re greeted by Il Duce’s colossal monument to himself: a 60-foot-high obelisk, engraved vertically with letters three feet tall declaring MVSSOLINI DVX. The obelisk, like much else about the Foro, was meant to evoke ancient Rome—the Romans had hauled eight obelisks back from Egypt to the city—and so was the wording: A “dux,” under the Caesars, was a military leader or governor, and the Roman alphabet had no “u.” Mussolini wanted his obelisk to be taller than any of the Egyptian ones. That required nearly 300 tons of Carrara marble. Its pointed top is gilded, and buried beneath its base, its existence unknown until a pair of classical scholars discovered archival references to it that they revealed in 2016, is a metal box containing a eulogy to Il Duce, written in Latin on parchment and hailing him (to quote a bit of it, according to the researchers) for his “regenerating Italy through his superhuman insight and resoluteness.”

Beyond the obelisk, the Foro’s northern entry opens onto a wide esplanade, the Piazzale dell’Impero. Along its outermost edges stand rows of marble blocks, each etched with a brief description of developments under Fascism that the regime was proud of: campaigns abroad, growth in grain production… Underfoot are a football field’s length of black-and-white floor-tile panels—crumbling, but still legible—commingling images drawn from Roman mythology and Christian legends with heroic depictions of Fascist militarism. Excavations during the 1930s, in particular one in Ostia Antica, the ancient port city outside Rome, were revealing impressive tiled pavings, and art historians today point to them as inspirations for the artists who worked on the Piazzale dell’Impero. Byzantine mosaics of the early Christian era were an influence too. Thus, a tiled portrayal of St. George slaying the dragon shares a panel along the walkway with a mosaic of a lorry, its truck bed filled with squadristi militia—the Blackshirts who roved Italy terrorizing union members, leftists, and others identified as opposed to the Fascist state. There’s a mosaic of Romulus and Remus, and there are mosaics of warplanes. And there’s DVCE, DVCE, DVCE spelled out again and again in bold black tiles—the crowd chant that greeted Mussolini whenever he appeared on the balcony of the Palazzo Venezia, his seat of government in Rome and private residence.

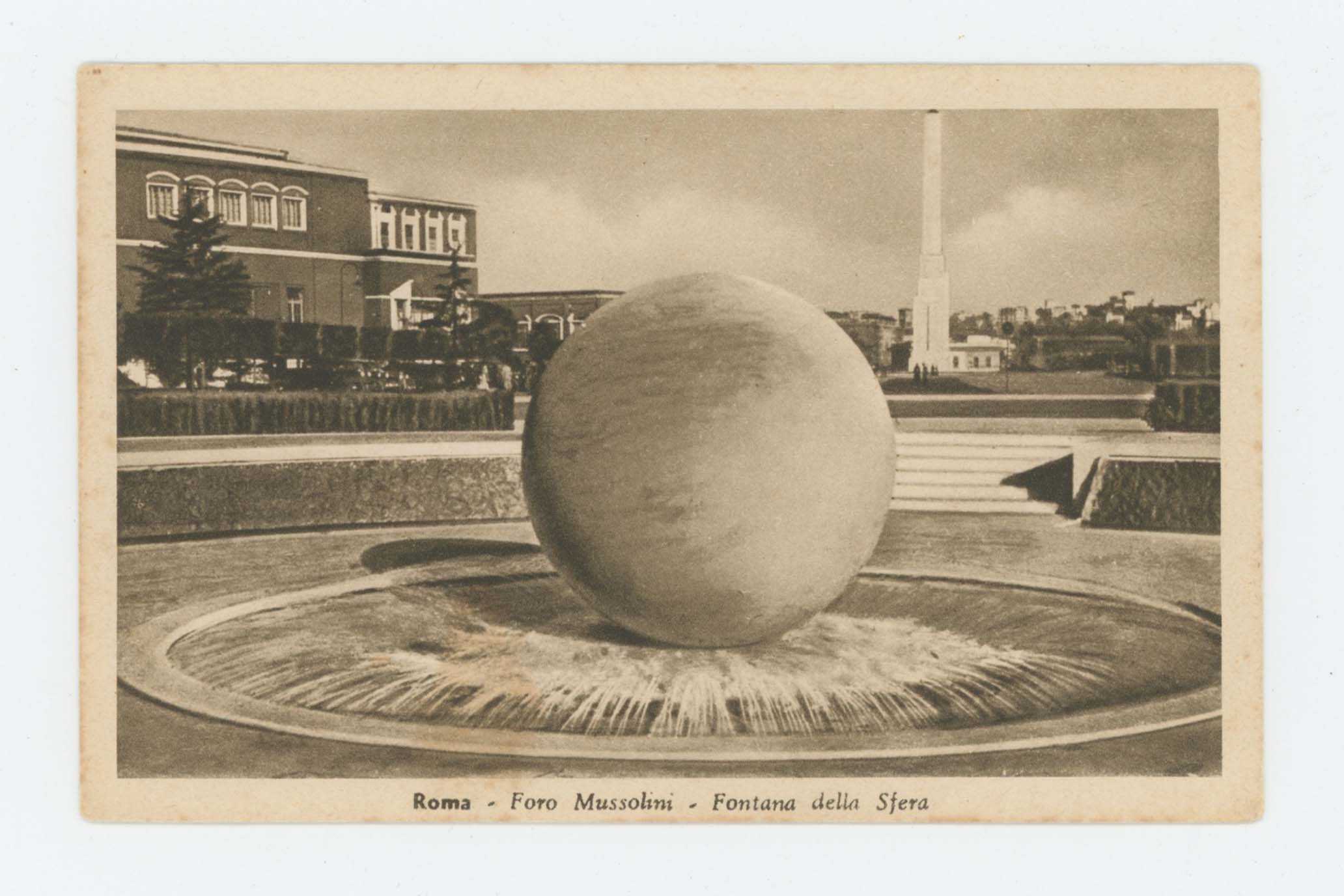

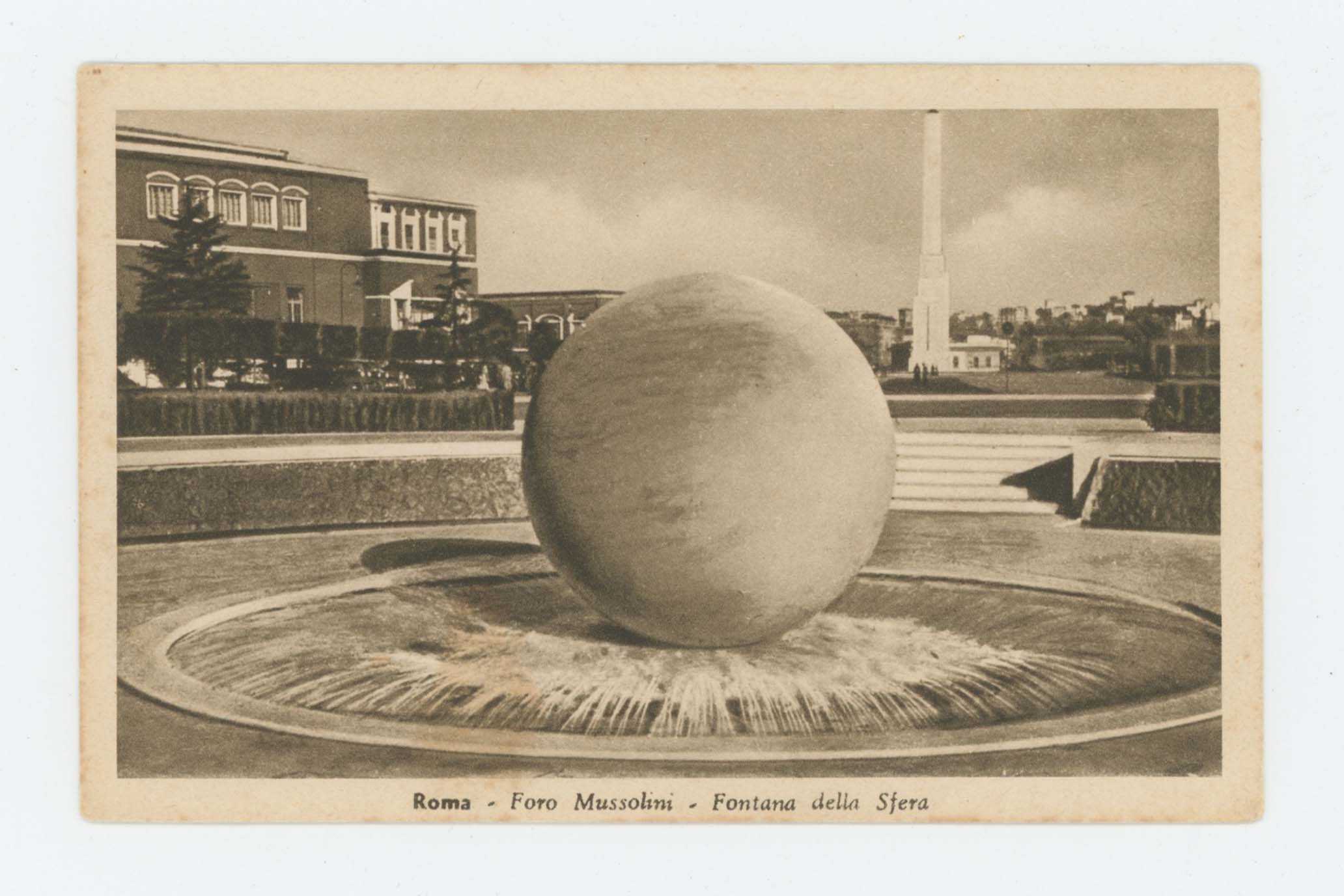

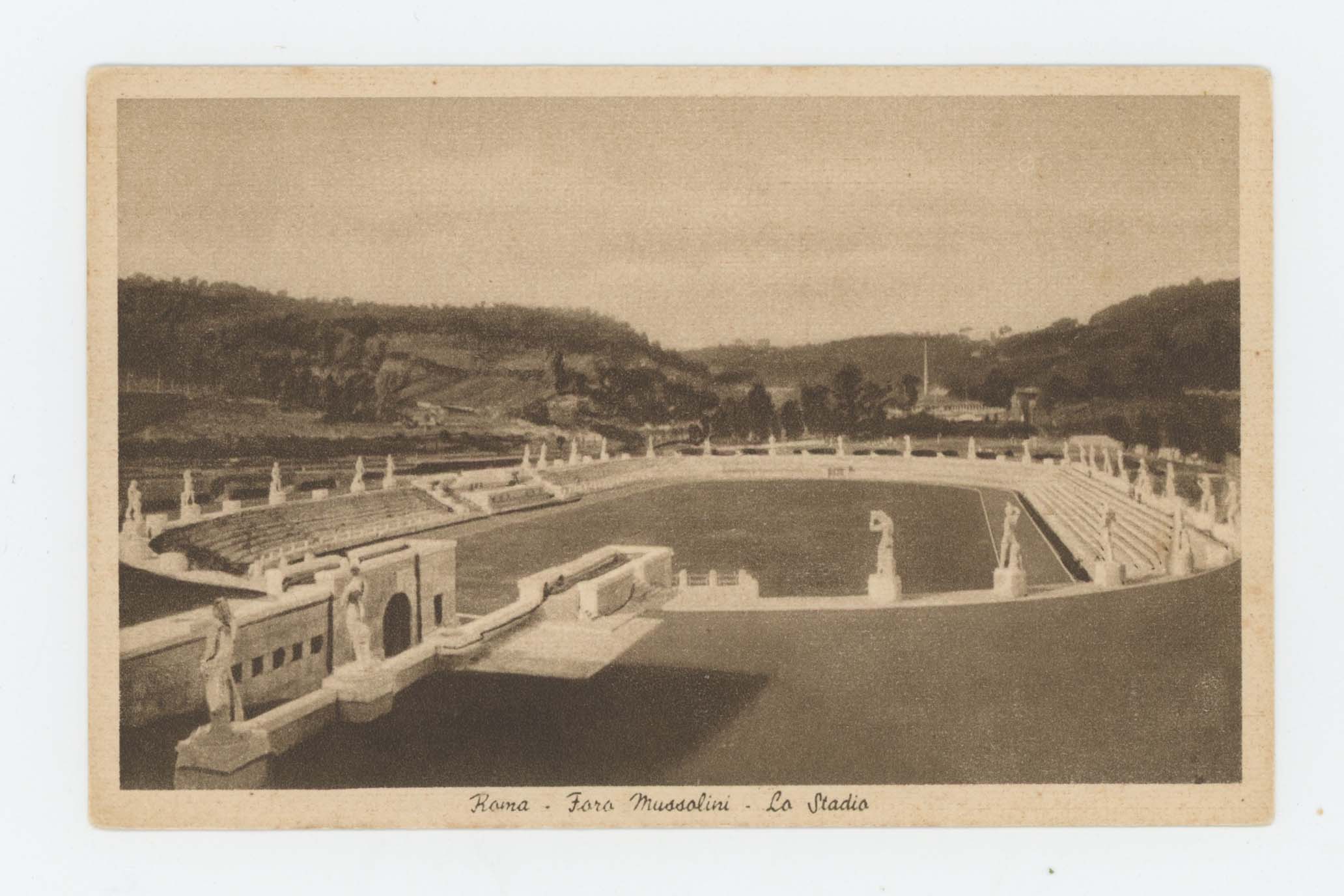

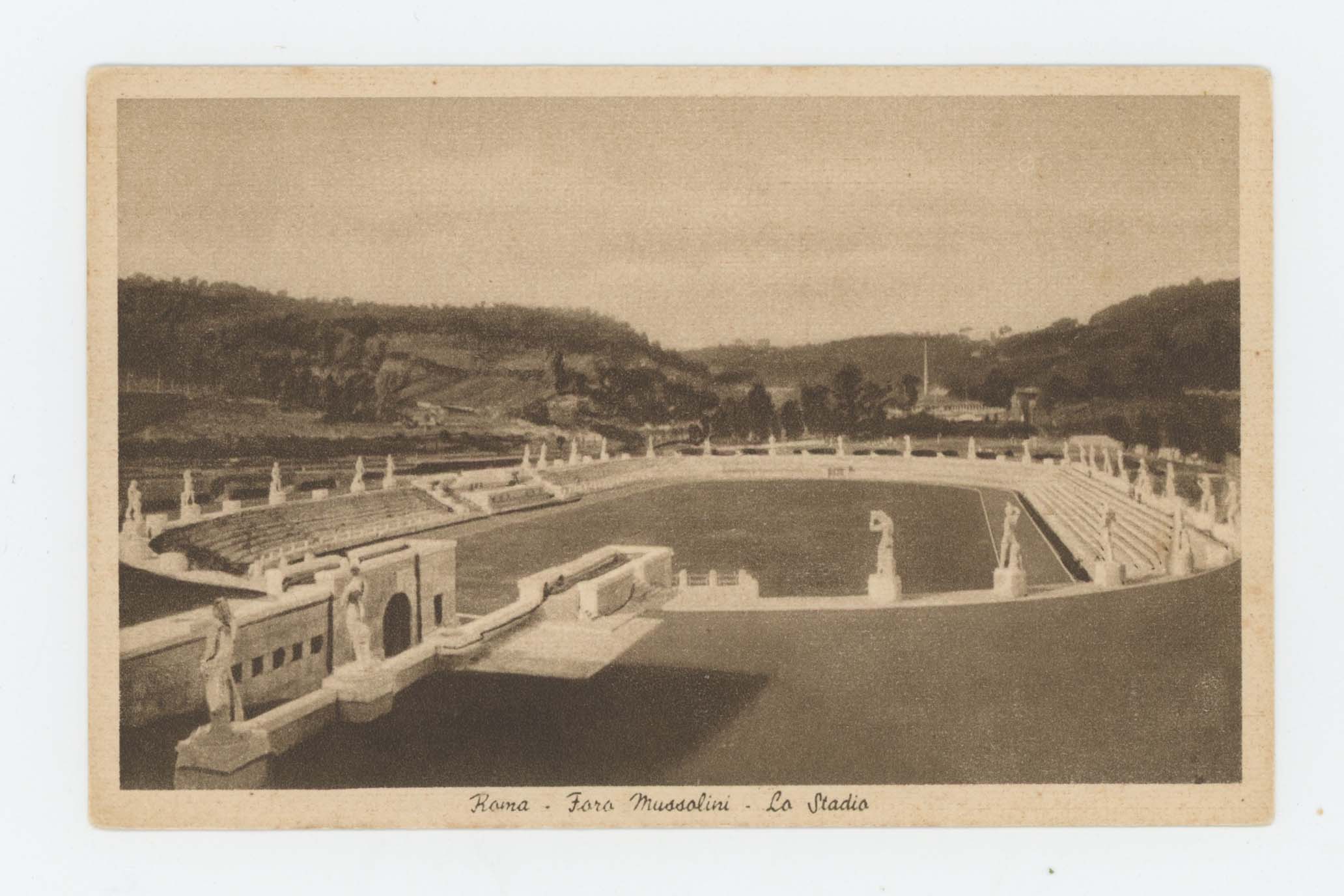

The tiled walkway of the Piazzale dell’Impero leads to a circular, sunken fountain, the Fontana della Sfera—a huge marble globe rests in its basin—and then onto the most arresting of the Foro’s romanitá re-conjurings: the Stadio dei Marmi. It was designed in the late 1920s and opened in 1932 as a track-and-field training oval for the future phys ed instructors enrolled a short walk away at the Academy. It’s encircled by marble bleachers, and the bleachers, in turn, are bordered by four dozen larger-than-life-size marble statues of male nudes. The references are classical, but we’re not exactly in Hellenic Greece or the Rome of the Caesars here. The poses struck by the carved figures are more like those of oiled bodybuilders at a Mr. Universe competition. Each was created in a different province of Italy—it was an undertaking meant to strengthen national unity—but the height and heft are uniform throughout the surround, the spacing between the statues, too. It is hard to believe that the overall effect ever registered as instructive, even among fervid Fascists: All the exercise in the world couldn’t give you bodies like these. But it must have resonated as impressively ambitious, visually compelling. It remains so—carefully maintained nearly a hundred years after its construction, radiantly majestic when the sun finds it. It can be disquieting, too, when happened upon in the stillness of its disuse, the statues staring blankly onto the still well-tended emptiness.

The neo-Hellenic look of the Stadio dei Marmi was reiterated in the design of a tennis stadium south of it in the Foro. Tennis had been brought to Italy by British expatriates, though it would be played on clay, as it was in France. It was most popular in Italy’s north, and it was in Milan where the Italian international championships were held, beginning in 1930. Mussolini liked tennis, played a little, though he didn’t like the word “tennis”—it was among the foreign words that, in 1929, he and his Fascists declared illegal to use. The game was to be called pallacorda, after an ancient game involving a ball and a string tied across a street. Italy’s international championships were moved to the Foro in 1935, and the Foro’s Stadio della Pallacorda, with its amphitheatrical layout, its hypermasculine statuary, and its seating on marble bleachers for 3,600 spectators, was the tournament’s main show court. It’s as striking, if not quite as grand, as the Stadio dei Marmi, and it continues in use today as the third show court of the Italian Open.

Was Mussolini there at the championships in 1935? How about his tennis commissioner, Uberto de Morpurgo? He was Italy’s best men’s player during the 1920s. He was from Trieste, and Jewish—a surprising and bitter irony, perhaps, for anyone who has read Giorgio Bassani’s heartrending postwar historical novel The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, with its Italian Jewish students in the northern city of Ferrara, in the wake of the 1938 racial laws, banned from the local tennis club and gathering regularly around a court on the grounds of the Finzi-Continis’ estate, anxious but with no sense (who could have seen it coming?) that the Finzi-Continis, among other Jews in Ferrara, would, beginning in 1943, be deported by the Germans then occupying central and northern Italy, and perish in a death camp. There were no tennis tournaments at the Foro by 1943. A world war was raging. The Italian championships held in 1935 were the last until 1950.

Along with its adoptions of ancient Roman visual forms, Mussolini’s regime (unlike Hitler’s) fostered a Modernist aspect, at least architecturally, and there are several examples around the Foro. This Rationalism, as it was called, could suggest a stripped-down version of a Florentine Renaissance palazzo, as it does in the Academy for Physical Education. Or, more adventurously, it could embrace an Internationalist-Style Modernism, which can be glimpsed, at the southernmost tip of the Foro, in the sleek, low-slung Casa delle Armi (House of Arms). Home to a fencing academy during the Fascist period, and today showing signs of years of neglect, it was designed by Luigi Moretti, who took over responsibility for the entire build-out of the Foro in the 1930s, and whose postwar career would go on to include the design for Washington’s Watergate complex.

Other modernist aspects of the Foro proposed during the Fascist period were never fully completed. Italy made a bid in the early 1930s to host the 1940 Olympic Summer Games, and the Stadio dei Cipressi, to be erected up a slope of cypresses in the foothills of Monte Mario, was planned as the main stadium. But Italy was not selected; Helsinki eventually was. As it would turn out, the war would lead to the cancellation of the 1940 Olympics. The Stadio dei Cipressi stood unoccupied, its design not fully realized. Italy joined the Axis in 1940, and that summer was busy occupying (or attempting to) a swath of southeastern France.

"Canadian Doubles." / MGM Studios

"Canadian Doubles." / MGM Studios

III.

After WWII, Italy underwent no large-scale, programmatic undertaking to rid itself of its Fascist remnants—nothing like the de-Nazification that was carried out in Germany, under pressure from the Allies. The United States, in particular, was more worried about Italy’s postwar Communist Party, which had emerged among the strongest in Western Europe, than any threat that Fascism might lurk, and one day be revived, never mind its monuments playing a role in that. Buildings, statuary, and many street names that evoked the years of Fascist dictatorship were left intact. As NYU professor of history and Italian studies Ruth Ben-Ghiat has pointed out, the Allied Control Commission recommended that only the most obvious Fascist monuments throughout Italy, such as busts of Mussolini, be removed. At the Foro, fig leaves were added to the statues of male nudes—which must have had to do with Catholicism, not erasing signs of Fascism—then fairly quickly removed. Mussolini’s forum was simply renamed the Foro Italico.

In 1955, Rome won the rights to host the 1960 Summer Olympics, and most of the Games’ events were held at the Foro. A large modern stadium, Olympic Stadium, was built on the footprint of the Stadio dei Cipressi, and a new center for aquatic sports went up at the southern end of the Foro, near the tennis facilities. (One of its codesigners was Enrico Del Debbio, who, 30 years earlier, had been responsible for guiding the overall design of Mussolini’s Foro. His associations with Fascism would catch up to him and his reputation in the 1970s.) There were a few political alterations made to the Foro grounds for the Olympics; the rows of engraved blocks along the Piazelle dell’Impero, for example, saw the addition of new ones summarizing that Fascism had, in fact, been defeated. But the stately figure of the battle-ready Balilla boy went untouched and stood poised above those making their way to the swimming and diving events.

Time brings forth new ways of seeing, and can silt and wear away intended meanings. The Foro has, for the most part, been de-Fascistified by the postwar gaze. The male nudes were, by the 1960s, beginning to be aestheticized as camp. Their romanitá stylizations—the contrivances, the histrionics—were foregrounded and ironized by art history. It was a fresh look, a La Dolce Vita regard, one that disengaged the statues from Fascism, judged them a little laughable, left them depoliticized. A generation later they were eroticized—see the black-and-white Mapplethorpe-esque photographs of them taken in the 1980s by George Mott, who cropped close in on nipples, pecs, and buttocks. The marble nudes were re-described as “expressing a virility that seems to have been conferred directly from the gods”—this the view of Giorgio Armani, who credits the Stadio dei Marmi with inspiring one of his advertising campaigns. They were thus powerfully compelling again, just not as originally conceived. The Rationalist buildings, meanwhile, were being put to use by new tenants. Their forms were strictly functional, after all. The Italian Olympic committee decided to make its home, and still does, in what had been the Fascist Academy of Physical Education.

Today, Italy’s Neo-Fascists (they number many) may make pilgrimages to Dovia di Predappio, Mussolini’s birthplace, but the Foro doesn’t have a similar resonance for them. The hard-right government of Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni—who, in the 1990s, joined the youth wing of a Neo-Fascist political party—is determined to keep out dark-skinned immigrants and denigrate gays and lesbians, not build a next Roman empire. There are, conversely, progressive Italian historians who have begun a project to map Fascist-era monuments, inspired by debates in the United States and some countries elsewhere in Europe over what to do with monuments celebrating slave owners and colonialism. The mapping project is backed by the Ferruccio Parri National Institute in Milan, named for an anti-Fascist partisan who went on to become the first prime minister of postwar, democratic Italy. The historians involved are not calling for any monuments to be destroyed. But they would like to see explanatory plaques affixed to them and hold out the hope, however faint, that Italy will finally have some sort of concerted reckoning with its Fascist past.

To spend a few days at the Foro was to glimpse many Romans expressing their innocent indifference to the built markings of that Fascist past—an attitude that comes easily, perhaps, to those living in a city that is a deeply layered palimpsest, its streetscape the stratified accumulation of thousands of years of rises and falls, reigns and vanquishings. Fans of the Roma and Lazio soccer teams, both of which play their home games at the Olympic Stadium, met up with their friends, as arranged, at the Mussolini obelisk. Local kids enjoyed skateboarding on the tiled surface of the Piazelle. Forgetting, like remembering, can be, for the victors at least, a quietly collaborative act of revenge, an unconscious expression of freedom and renewal. Tony Judt, an English historian of Europe, and a man of the left, wrote in his magisterial book Postwar that “without collective amnesia, Europe’s astonishing post-war recovery would not have been possible.” He quotes an Italian newspaper headline published the spring day in 1945 that the world learned Hitler was dead: “WE HAVE THE STRENGTH TO FORGET.”

I was at the Foro among thousands of shirtsleeve Italians who’d gotten past the past as we settled in, on a Sunday afternoon, to watch a second-round match between the young Italian hopefuls Lorenzo Musetti and Matteo Arnaldi. Italians, like fans everywhere, are nationalists when given the opportunity, and to see the all-Italian matchup at the Italian Open they crowded the onetime Stadio della Pallacorda, now the Stadio Nicola Pietrangeli, named for the Italian star of the late ’50s and early ’60s (he won two French Opens). Size-wise, Pietrangeli is one of those just-right venues, big enough for spectacle yet still small enough for intimacy—like the old No.2 Court at Wimbledon, and the now-gone Bullring at Roland-Garros. Those of us jammed on the stadium’s stone bleachers were joined by an encircling throng of standing spectators, the sunken-amphitheater design affording them decent sight lines even as they clogged and jostled three deep.

A milky sun glinted now and then off the heroic nudes, most of them arrayed with teenagers who’d hoisted themselves up on the statues’ pedestals for better views. The tennis was good. (Musetti, 6–4, 6–4.) The red clay, the white marble, the green of the soaring umbrella pines beyond: It was its own enclosed world, a sporting garden, and out of time, deepening the here-now absorption we are seeking whenever we show up to watch a match. The moment provided little room for the past, though the colossal Balilla boy was visible to anyone who turned and looked above the north end of the court. On this afternoon he cast no shadow.