Damage Control

Damage Control

Excerpt: Changeover: A Young Rivalry and a New Era of Men's Tennis.

Excerpt: Changeover: A Young Rivalry and a New Era of Men's Tennis.

By Giri NathanAug 19, 2025

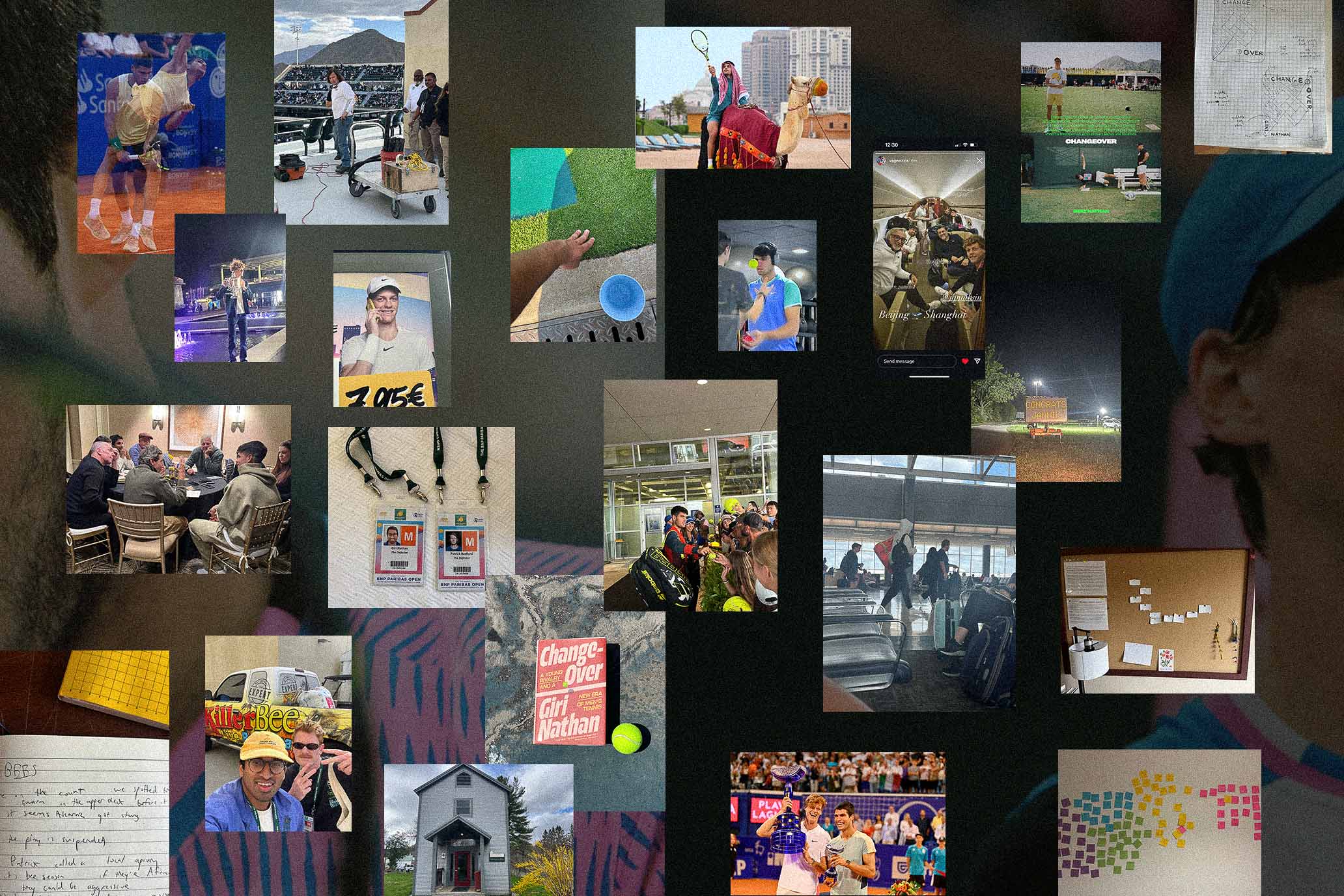

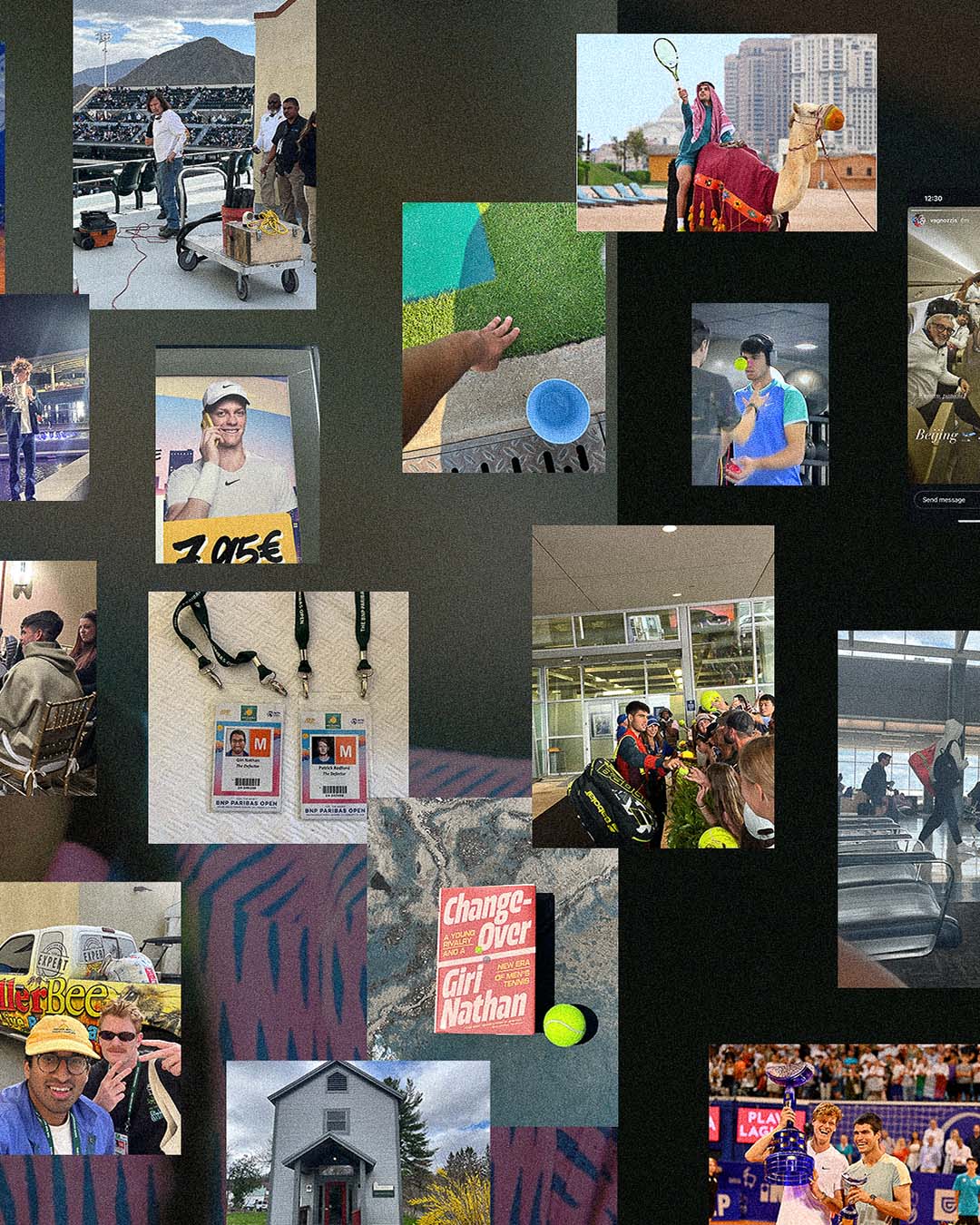

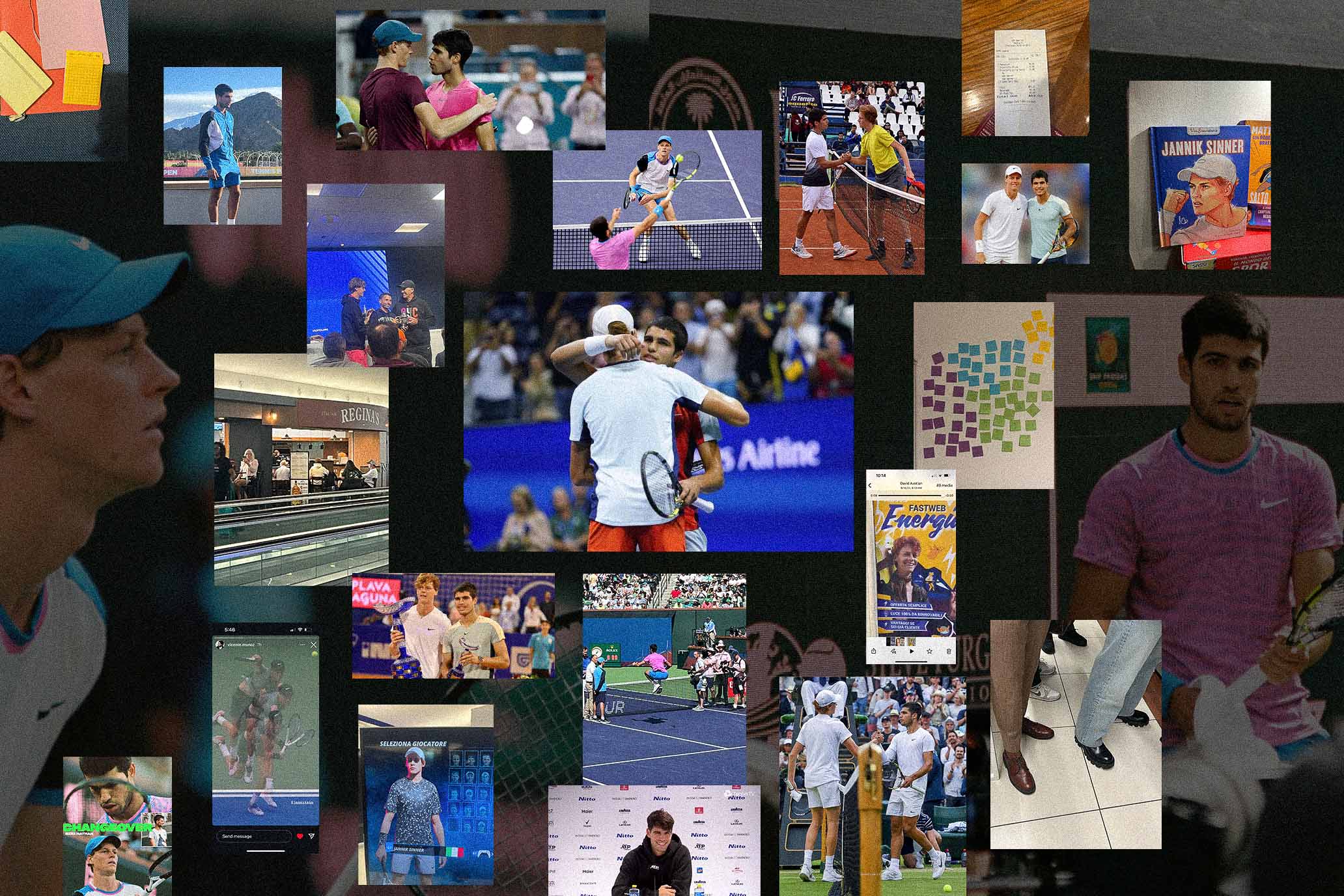

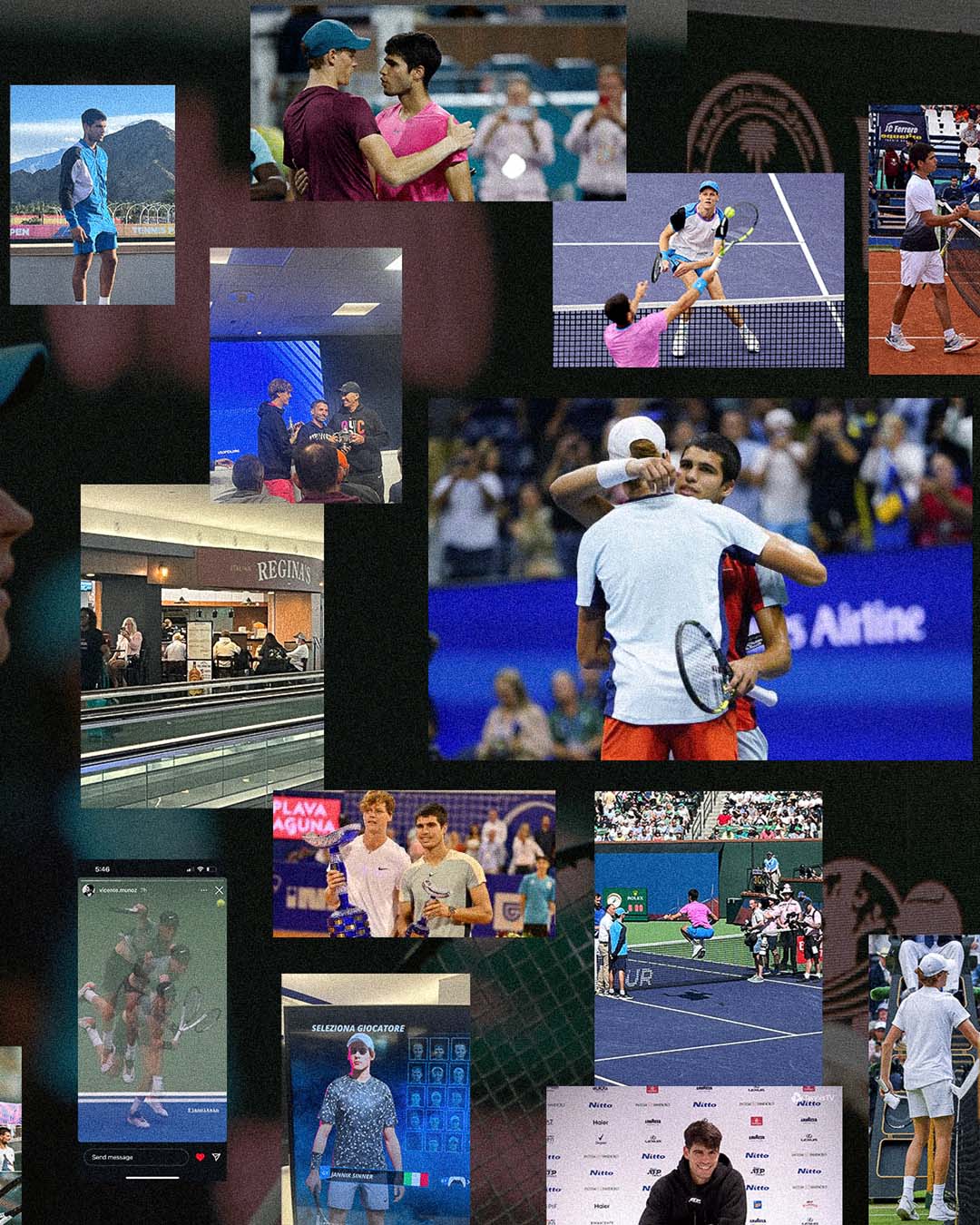

Giri Nathan's mood board for Changeover.

Giri Nathan's mood board for Changeover.

These days, to talk to a player in a truly relaxed state, you often have to catch them at the outset of a tournament, before the churn and toil begin. That hasn’t always been the case. The membrane between journalist and player was more permeable back in the day. The veteran tennis journalist Jon Wertheim told me that at the turn of the millennium, he could speak to Venus Williams privately for half an hour in the middle of a tournament; my eyeballs plopped out onto my keyboard. Curry Kirkpatrick, who wrote fizzy profiles of players for Sports Illustrated throughout the eighties and nineties, told me stories about ambling up to Andre Agassi at a swimming pool and bickering with John McEnroe on a walk after he’d written something not quite to the hothead American’s liking. The notion of a player today submitting themselves to the critical eye of a journalist, for meaningful conversation, was essentially unthinkable. Tournaments have whittled away the zones where players and writers could commingle. Storytelling is consolidated in the hands of the players.

Sports media is dead; most of what’s left is window dressing for online sports gambling firms.

Print journalists have become unnecessary middlemen for athletes who can instantaneously transmit their idle thoughts to fans on social media. To expand his popularity, a player relies not on a ferrety writer, but on a well-cut highlight reel or a high-end photo shoot. I understand the calculus: When your own time becomes so valuable, why give away access to your life story for free? There has to be something in it for them, too. A brief, canned sit-down interview might be an acceptable cost to promote a needy sponsor, or to secure a sumptuous cover shoot, which yields photos that can be tossed on Instagram to slake thirsty fans. The image has fully stomped out the written word in sporting culture, if not culture full stop. Players with enough clout can even partake in another current pastime: the hagiographical docuseries, where the player gets full editorial veto power. As noted, Netflix cameras trailed Alcaraz for chunks of the 2024 season. What we lose, in this new media ecosystem, are the thornier narratives that the players themselves don’t want to share.

Aside from this broader societal shift, there’s also been a tennis specific shift: The athletes have gotten a lot more sophisticated about whom they hire for their “team.” Top-ranked players have become business executives, constantly hiring and replacing personnel. Typically, the team consists of the following. There is the agent, to secure the endorsement deals, sponsorships, and appearance fees. The coach, to hone tactics and technique—sometimes two, with different emphases, as Sinner has in Darren Cahill for the bigger picture and Simone Vagnozzi for the fine details. The strength-and conditioning coach, to keep nudging the body toward its optimal state. The physiotherapist, to help a banged-up body recuperate after matches. There might also be a sports psychologist and a nutritionist. Much of this staff travels the world with the player, and unlike in team sports, where a franchise handles the overhead, players have to pay their employees out of their own earnings. In a 2021 interview with Sports.ru, Andrey Rublev estimated his annual expenses were about $600,000; even that was on a down year for travel, and more than a few players have an even larger full-time staff than his.

The rapid expansion of the player team is a consequence of rapidly increasing prize and sponsor money in the sport. The titles won them glory, and the agents leveraged that glory to win the player even bigger checks. Winning Roland-Garros in June, for example, earned Alcaraz €2.4 million from the tournament. But a few weeks earlier, he had signed a long-term contract with Nike that paid him roughly $15 to $20 million a year, according to the Spanish outlet Relevo. Sinner had signed a similarly structured Nike contract in 2022, about $150 million over 10 years, before he had won much of note. The apparel companies were already flinging around the sorts of sums they had paid to the Big Three. In a famous round of corporate bidding, Roger Federer had been lured away from Nike to Uniqlo with a 10-year, $300 million contract. Even apparel companies outside of sport wanted a piece of the new kids. Sinner became an ambassador for Gucci, and in 2023 the luxury brand had to persuade Wimbledon to permit a brownish duffel bag that broke the tournament’s militant all-white code. The Italian’s leggy frame and glassy expressions hold up surprisingly well in the context of a fashion shoot. Alcaraz’s brawnier build, meanwhile, had him modeling underwear for Calvin Klein.

Armed with these bankrolls, the Big Three could afford to reinvest in personnel to help prolong their careers and earning potential. This became a new template for the present stars to follow. But as the tennis journalist Ben Rothenberg told me, young players ensconced in these huge teams can also become “siloed and isolated,” spending most of their lives around people on their payroll, marinating in a tour culture that is increasingly sterile. The personalities are becoming a little less freewheeling and inquisitive, a little more coddled and calculating. We cherish someone like Daniil Medvedev because he is an outlier to these trends. He seems to be one of the last people speaking his truth at all hours, sometimes to his financial detriment, always to our delight.

There’s a lull before every tournament called “media day.” Players have arrived on the premises, and they’re practicing, but not yet playing official matches. They are thus ripe to be turned into Content. They spend a decent chunk of that day recording clips that will be circulated on social media to promote the tour. Part of the day is set aside for journalists. Select players of interest are trotted out for a casual roundtable discussion, which at the Cincinnati Open was taking place in the dining area of a little golf club across the street from the tournament venue. These discussions, which were each set to last around eight or nine minutes, were also susceptible to starting eight or nine minutes early, as Sinner’s did; the player’s schedule overrules all others’. He popped into the golf club looking tanner than I remembered, as if his skin were bronzing to match his hair, and wearing a white-and-black hoodie that seemed like overkill for the 84-degree afternoon. He talked us through his summer of ailments—hip pain in the clay season, an unnamed illness at Wimbledon that left him woozy, the tonsillitis that knocked him out of the Olympics—and ended with a bit of Zen. “You know, sometimes you have to accept this.” The hip in particular had looked sketchy in his most recent match in Montreal, a loss to Rublev, where Sinner had been clutching at it for the better part of an hour. When I asked if it was still bothering him, he said it wasn’t, and he was “not afraid.”

But he wrapped up on a muted note, as if he just wanted to get some match reps in Ohio to get in shape for the imminent U.S. Open, the year’s last major.

In Cincinnati, Sinner and Alcaraz were the first and second seeds respectively and could meet in the final. Djokovic was still recovering from his Olympic bliss and would not play the role of the chaperone at the teen dance making room for the Holy Spirit between the youthful duo. Alcaraz showed up on media day in the boxy white tee that had become his pre-tournament staple, speaking fondly about the “epic” final he’d lost to Djokovic at last year’s tournament. Asked whether the suburban environs relaxed him, he laughed; this was still a 1000-level tournament, and he was fighting to end the year as the No. 1 player in the world, a race that Sinner still led despite Alcaraz’s rare double at Roland-Garros and Wimbledon.

Alcaraz was asked once again about playing alongside Nadal at the Olympics, and I was vaguely depressed to hear him recycle almost verbatim an answer I’d heard before. I felt for him, and for those trying to coax a tasty quote out of him. Every journalist seemed to want the Nadalcaraz doubles to have been a transformative experience for the junior Spaniard, and while I’m sure it was on some level, it might not have been the Yoda-like transmission of wisdom we hoped to depict it as. Again I was reminded that sports writing isn’t so much tracing the truth as telling a story with a satisfying shape. I could almost mouth the words as Alcaraz repeated what he’d learned from Nadal on court: “Sometimes when we were down, he was there in a positive way, talking to me like, ‘Well, right now they are gonna feel the pressure. We have to just stay there, putting some balls in, trying to get them in trouble.’ Some situations, some things that you probably don’t see—or is difficult to see—he sees very clear.” Alcaraz was always cooperative with reporters, and he didn’t switch on autopilot the way Sinner sometimes did. It was hard to blame a 21-year-old for reusing an old line. Maybe today’s players had reason to prefer recording breezy video clips about who the funniest or most handsome player on tour was, when the alternative was talking to us obsolete scribes with our little recorders.

Click here to order Changeover.

Giri Nathan's mood board for Changeover.

Giri Nathan's mood board for Changeover.