Tennis as Death

Tennis as Death

Review: Andrey Rublev: Breaking Back

Review: Andrey Rublev: Breaking Back

By Owen LewisJul 5, 2025

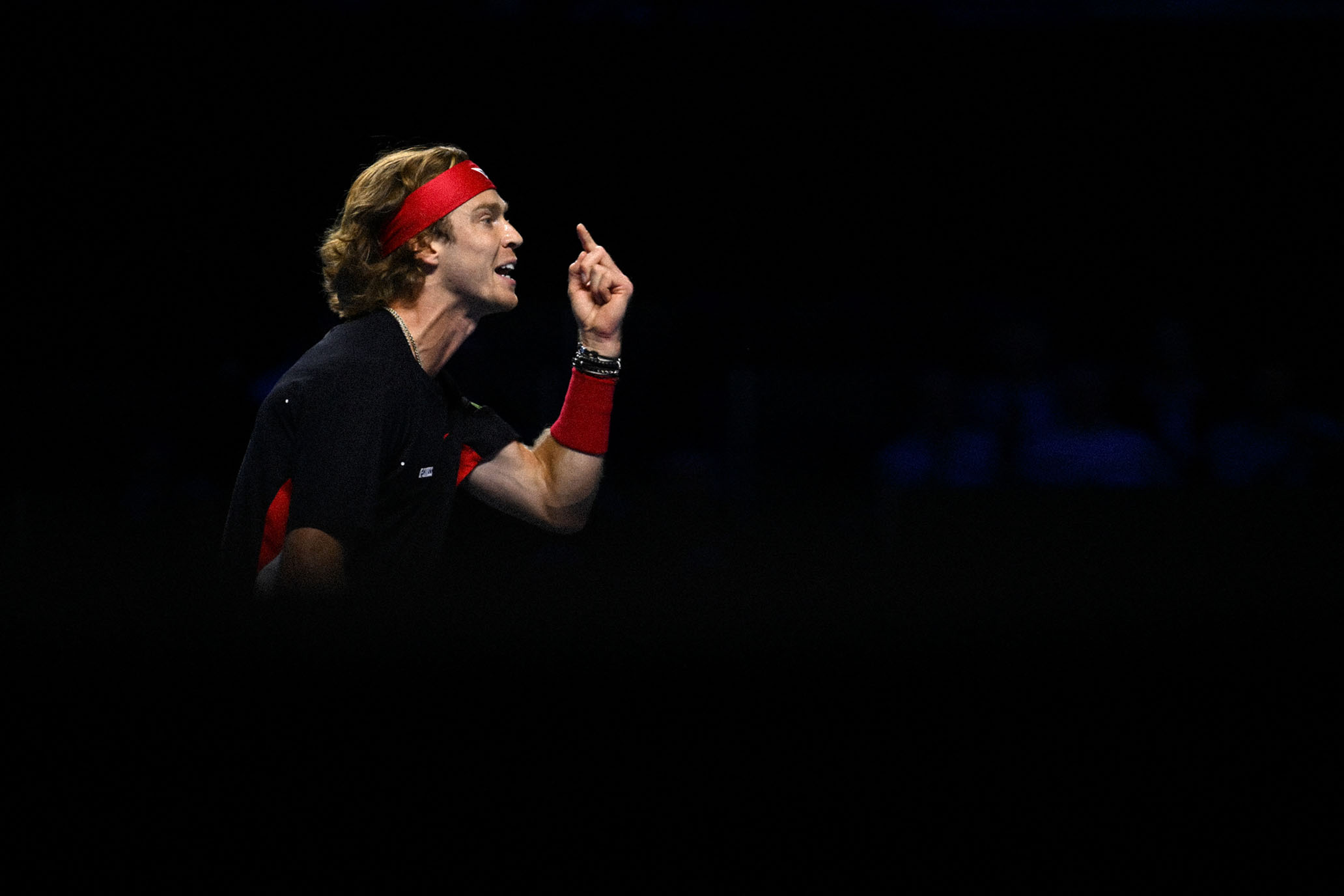

Andrey Rublev during darker times, at the Swiss Indoors Basel. // Getty

Andrey Rublev during darker times, at the Swiss Indoors Basel. // Getty

The first look at Andrey Rublev in his YouTube/ATP Tour documentary Breaking Back comes via his countryman Karen Khachanov. “It was an under-10 tournament in Russia, and I heard from a few courts behind me screams, crying,” Khachanov says. “One boy was laying over, throwing balls, racquets. They told me, ‘His name is Andrey Rublev.’ I say, ‘Very good. Nice to meet you.’ [Laughs]”

That Khachanov seemed unsurprised in his recollection is no coincidence—this sport has a way of desensitizing the shock of watching a player act out their self-hatred. At the 2008 Miami Open, Mikhail Youzhny raged so fiercely at his cowardice for a pitty-pat backhand into the net that he turned his racquet on his own brain, whacking his forehead with the strings until dark blood trickled down his scalp. Even this disturbing masochism earned only a blithe look from his coach, and a startled emoji in Tennis TV’s caption for the video when, in 2021, they released extended highlights of the match. Compare that reaction with the uproar over Aryna Sabalenka’s salty comments after losing the Roland-Garros final to Coco Gauff, and you’ll have a good idea of how much these tantrums move the emotional needle for most observers.

Rublev, though, took self-recrimination to such a visceral degree in his darkest years that many grew uncomfortable while watching him play. His fury was not only destructive but desperate. He’d howl after a miss, eyes practically pulsing out of his head. He drew blood from his knee via repeated racquet whacks. At the 2024 US Open, after a shoddy forehand error, Rublev clapped his left hand onto his racquet strings with such force that he cut it and needed medical attention. The miss came at 3–1 in the first set, so early on that it couldn’t possibly have proved costly all on its own. No tennis mistake is worth losing blood over; even if one could be, this wasn’t close to being it.

In Rublev’s on-court interview following his fifth-set tiebreak escape from a fourth-round match with Holger Rune at the 2023 Australian Open—Rublev had had so many leads he’d never be able to think about anything else if he’d lost—he likened crunch time to being held at gunpoint. He crosses himself when his matches end, suddenly seeming to gain a measure of peace, win or lose. In light of quotes like this, it made sense. After hours of feeling like life hung in the balance, I’d accept salvation or oblivion too.

“When you were watching him, you were saying, ‘Okay, he has a lot of potential,’” Galo Blanco, Rublev’s coach and agent, says in the documentary. “‘But he’s completely crazy.’” Breaking Back efficiently chronicles how Rublev ended up so tortured: He was raised with the mindset that tennis mattered above all else, so when his tennis began to fray, so did his world.

The stifling pressure to win a major title only worsened his anxiety (a word Rublev repeats dozens of times throughout the doc, and pronounces “ank-shitty”). Rublev takes the gun-to-the-head metaphor even further to the ATP’s cameras: “Every time I was going on court and things were not going my way, the feeling is like you’re dying. It’s like someone came to murder you.” When Rublev lost, he felt like that someone had succeeded.

In off-court moments on camera, Rublev is light and genial, poking fun at himself and others, eagerly hugging his friends. Compartmentalization can rip perception from reality, that I knew. I also wondered whether Rublev might have been happier in previous years if he’d quit tennis. The tragic thing, as an observer, is that his violent reactions after his errant shots seemed only to ruin his mental health rather than improve his tennis. He is sublimely skilled, better than you or me or everybody on the planet except a dozen or so people could ever get at tennis. But he is also limited. His big forehand is his best shot; it will never be as big as Jannik Sinner’s. He does everything well and nothing as well as Carlos Alcaraz. When Djokovic rips into himself, you get it; you’ve seen what he can do at his best and understand how anything short of that glorious, stifling peak is a disappointment. Rublev, who has made 10 major quarterfinals and lost them all, demanded a perfection from himself that he was incapable of producing.

In time and after a lot of pain, tennis-related and not, Rublev came to realize that expectations of winning a Slam were “bullshit,” that he’d die for real at the rate he was going. “I still love [tennis],” he says. “I still want to achieve as much as I can, but in a healthy way, not a struggle way.”

The realization is euphoric. To this viewer, the expectation that top players win a major is indeed hot crap. A player’s chances of doing so depend almost wholly on how many years in age separate them and various generational talents, who gatekeep the game’s shiniest prizes with a Cerberusian vigor. If Rublev were to win a major, he’d earn the privilege of brief catharsis and Big Three-pilled fans calling the crowning achievement of his career a “Mickey Mouse title” for the rest of time.

Rublev seems to be suggesting that the goal of a financially sustainable tennis career should be to escape with one’s mind intact. Players frequently find it unfulfilling to reach their lifelong objectives—think of Agassi writing in Open that he felt nothing once he reached the top spot in the rankings, or Dominic Thiem losing all his motivation after he finally won a major. The price for these cold prizes is high. Expectations spiral ever higher, unavoidable losses keep you up at night (Djokovic, tennis king of kings, has lost 13 major finals), you play even more matches. The real achievement, then, is not going crazy while navigating this demented maze, to reserve a bit of yourself from the game. Give everything to tennis, and what you get back will be inevitably less.

As top-ranked players have suffered upset after upset at this year’s Wimbledon, Rublev has progressed through the draw calmly, making the fourth round to live up to his 14th seed. Hiccups that once would have had him screaming his vocal cords raw—a missed match point and a fourth set in his opener against Laslo Djere, back-to-back double faults as he tried to serve out his third round against Adrian Mannarino—he now accepted with grace. Against Mannarino, Rublev hit a sick, sliced forehand pass on the defensive in the final game, a shot you’d have thought came from Carlos Alcaraz had the video stream blurred out the player who hit it. An ace on the next point sealed his win. Never did I worry that he was going to hurt himself.

Rublev sits on the beach at the end of the documentary, giving a voice-over that sounds driven more by philosophy than by the fiercely competitive instincts that power elite players. He is sleeping better and spending more time with himself. “It’s not easy because it’s super painful in the beginning,” he says of fixing himself. “But then it’s relief.” Watching him suffer the beginnings of a choke at moments during his Wimbledon run and react as if only a tennis match is at stake, not his own life, I see what he means.

PURE, ORIGINAL TENNIS — SIGN UP!

RECOMMENDED

The 2026 Australian Open Shoe Report

SHOE REPORTS

Zeynep Sonmez Brings the Ruckus

AUSTRALIAN OPEN

Mixed Doubles

OPEN TENNIS — VOLUME 2